Telling Stories About Ourselves: Zia Anger’s Radical Mythmaking

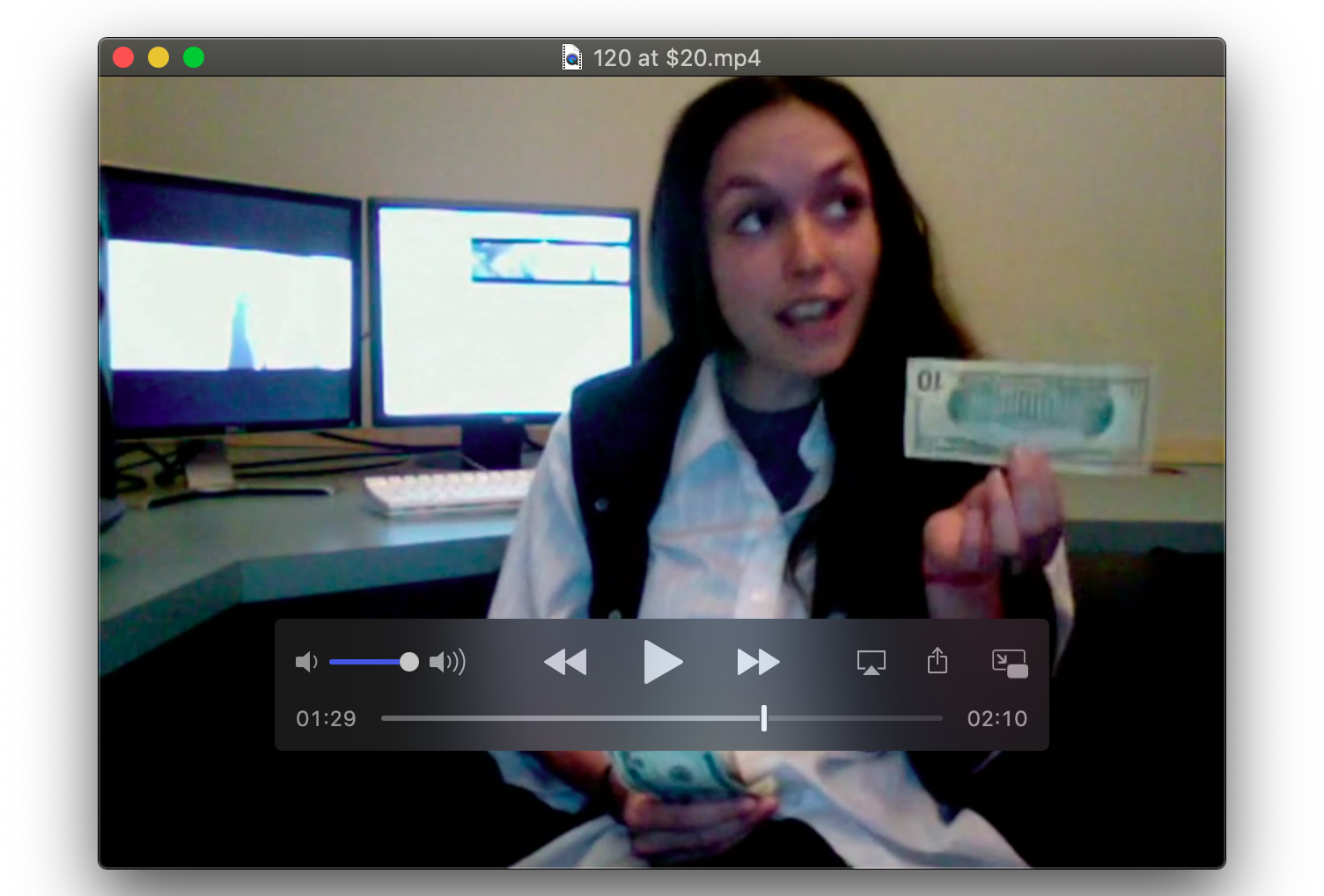

Zia Anger, My First Film (screenshot), 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

“So before we get too far into this, I have to tell you this is a bad film. It’s a bad film like most people’s first features. But if you are honest and have a bit of talent that’s okay.”

—Zia Anger, My First Film

Share:

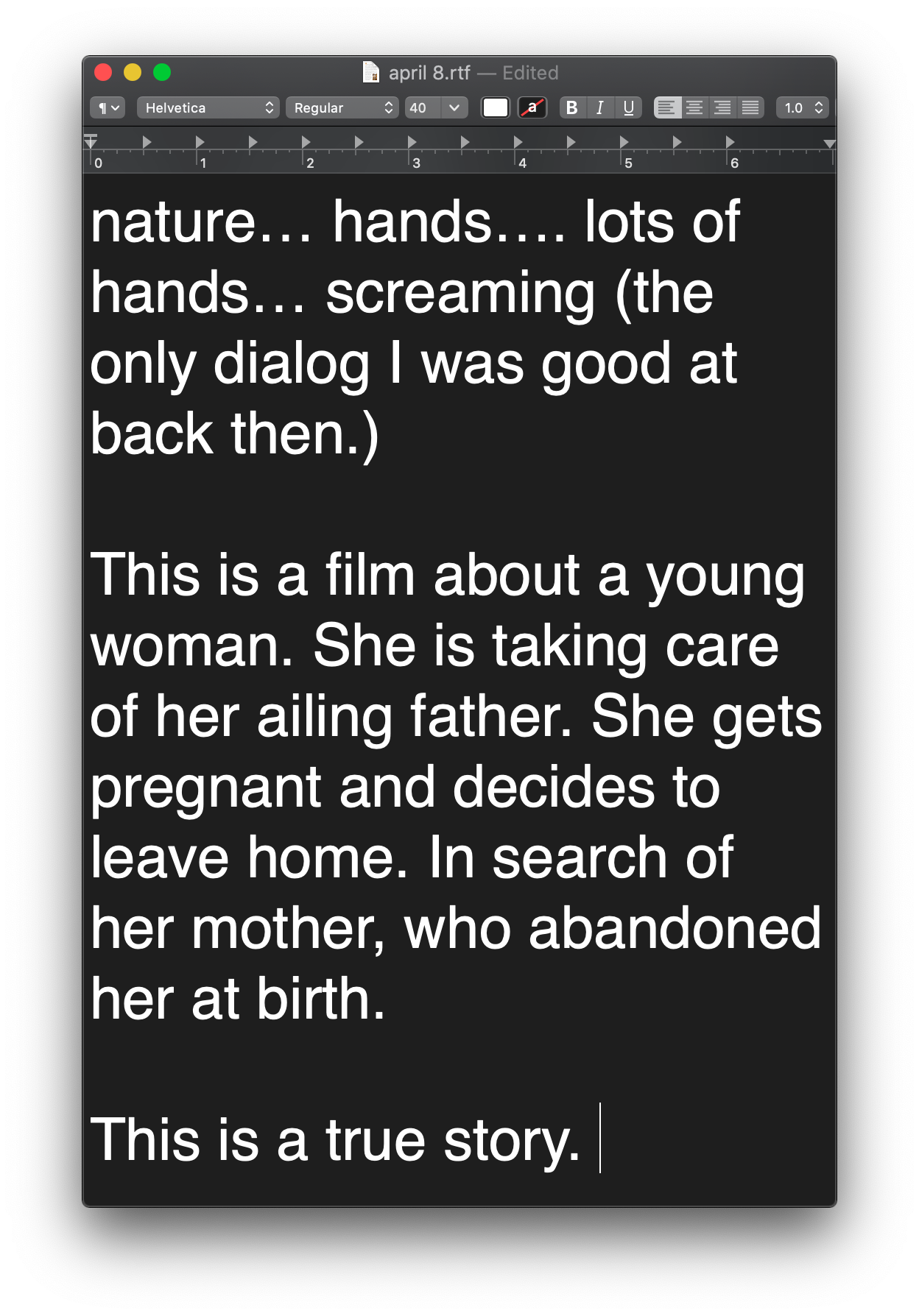

Zia Anger will be the first to tell you that Gray was not a successful movie. Created on a shoestring budget via Indiegogo between 2010 and 2012, the filmmaker’s first feature, about a young woman’s journey back to her hometown, was an ambitious failure. Friends and family from Anger’s actual hometown served as her cast and crew, and after a grueling and arguably cursed filming, Gray was rejected by almost 50 festivals and never received distribution. On industry databases, the film is still listed as “abandoned”—a forgotten project when considered through the marred lens of Hollywood’s capital and business transactions.

In the years since Gray (aka Always All Ways, Ann Marie), Anger has built a fascinating body of work. In addition to spellbinding music videos for Beach House and Maggie Rogers, Anger has crafted experimental shorts such as I Remember Nothing and My Last Film (both 2015). Gray’s cinematographer, Ashley Connor, has also found a home in the industry, shooting Desiree Akhavan’s The Miseducation of Cameron Post and Josephine Decker’s Madeline’s Madeline.

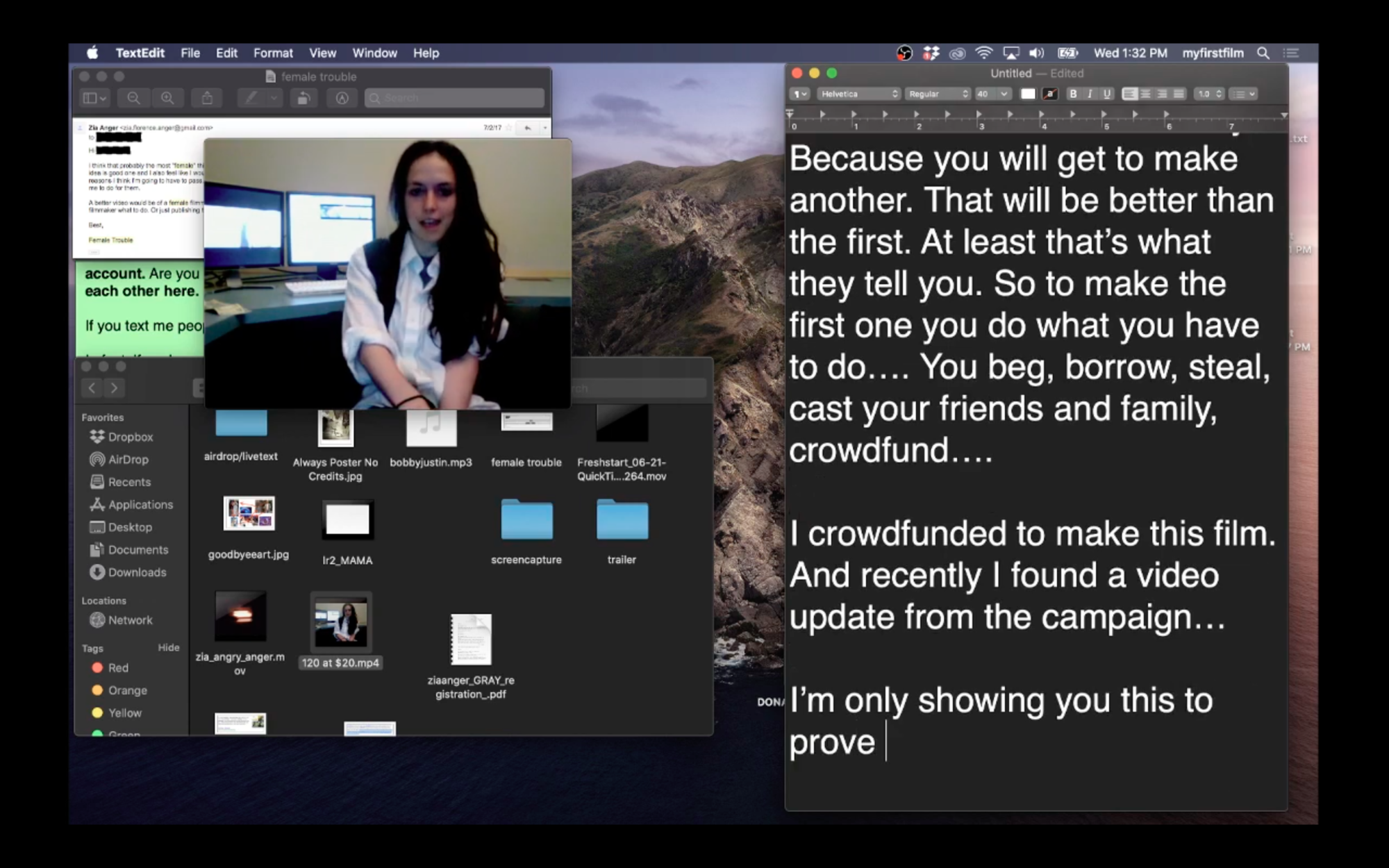

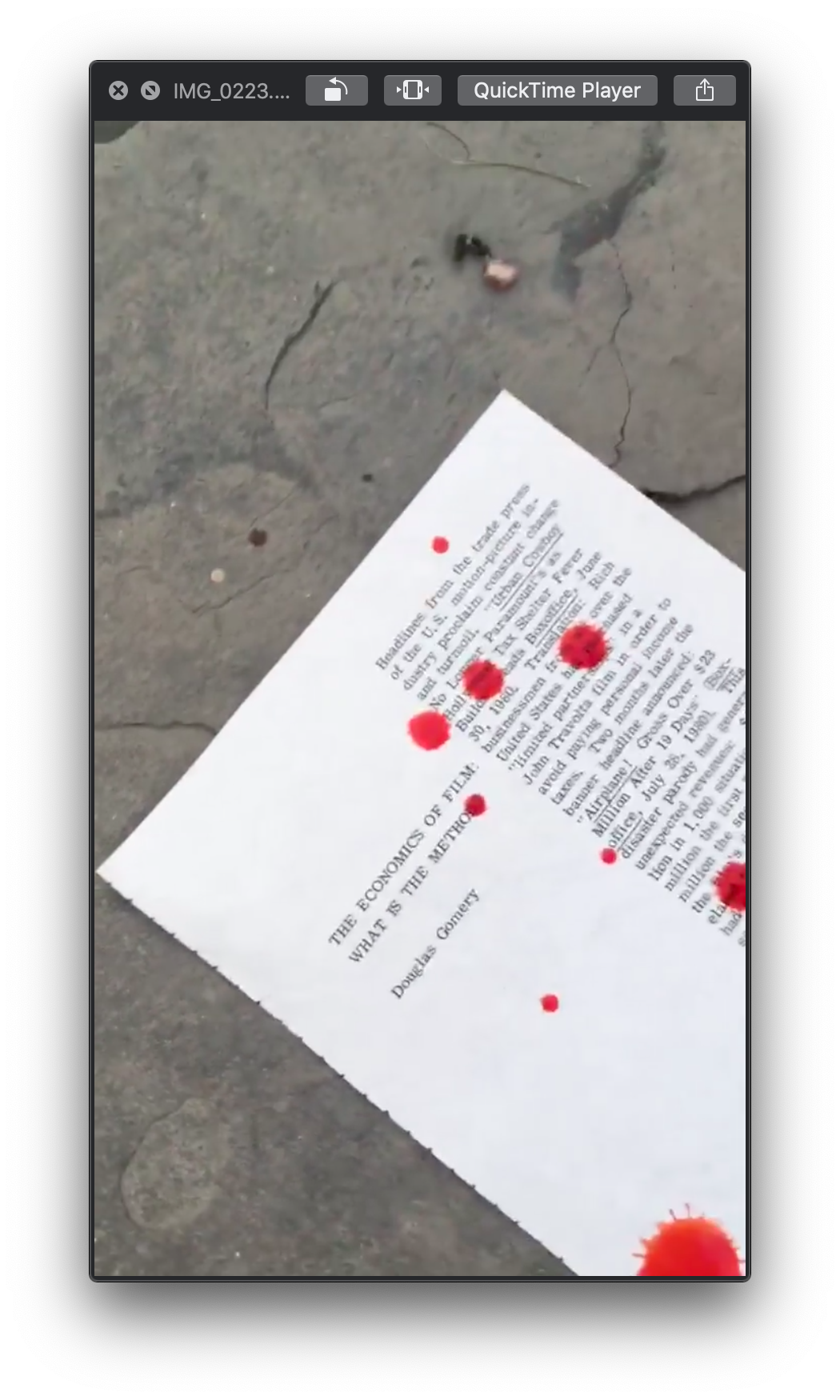

It would have been easy for Gray to be truly abandoned—for another film to be Anger’s first and for Gray to be lost forever—but instead, Anger repurposed her footage and turned Gray into something else entirely. The resulting project, aptly titled My First Film, is a hybrid of performance art, moving image, and monologue that reuses clips of Gray alongside a live projection of Anger’s computer screen. Through TextEdits, screencaps, and video footage, Anger tells the story of filming Gray, and she slowly reveals how its coming-of-age story mirrors and radically diverges from her own life.

Zia Anger, My First Film (screenshot), 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

My First Film has been received rapturously by both viewers and critics. Richard Brody of The New Yorker described it as “vastly imaginative and politically trenchant” in its analysis of Anger’s personal and artistic life. With such raves in tow, Anger performed to arthouse and museum audiences across the US in 2019, with plans to bring My First Film to Europe in spring 2020. COVID-19 rendered those plans impossible, but instead of retreating, Anger announced on Twitter that she would live-stream performances of My First Film. In what could have been a case of a brilliant work lost in translation, the fully digital version of Anger’s masterpiece instead maintains its searing insights on family, grief, and moviemaking. In doing so on its alternative platform, My First Film is even more resonant to our self-reflective and quarantined state.

Other filmmakers have struggled with online screening: they argue that their films are incompatible with small computer screens and that new platforms are not economically viable. For Anger, the switch was natural and offered benefits not previously available. The new digital set-up, done in part with help from the production studio MEMORY, came together relatively quickly. Through email correspondence, Anger said that setting up the livestream took “technical checks and tech research” along with a “fair amount of rehearsal time and thinking about the show in a new context.” She set up private screenings to get feedback from “one or two friends and family,” but admits that she’s learning the most about the new platform through her live performances.

Zia Anger, portrait, 2020 [photo: Theo Anthony; courtesy of the artist]

Shows (and the occasional public rehearsal) were announced only through Anger’s Twitter and sold out regularly. Although online screenings have given many viewers their first opportunity to see My First Film, Anger is still working on making this experience as accessible as possible, including special screenings with closed captioning and donated tickets for people unable to pay.

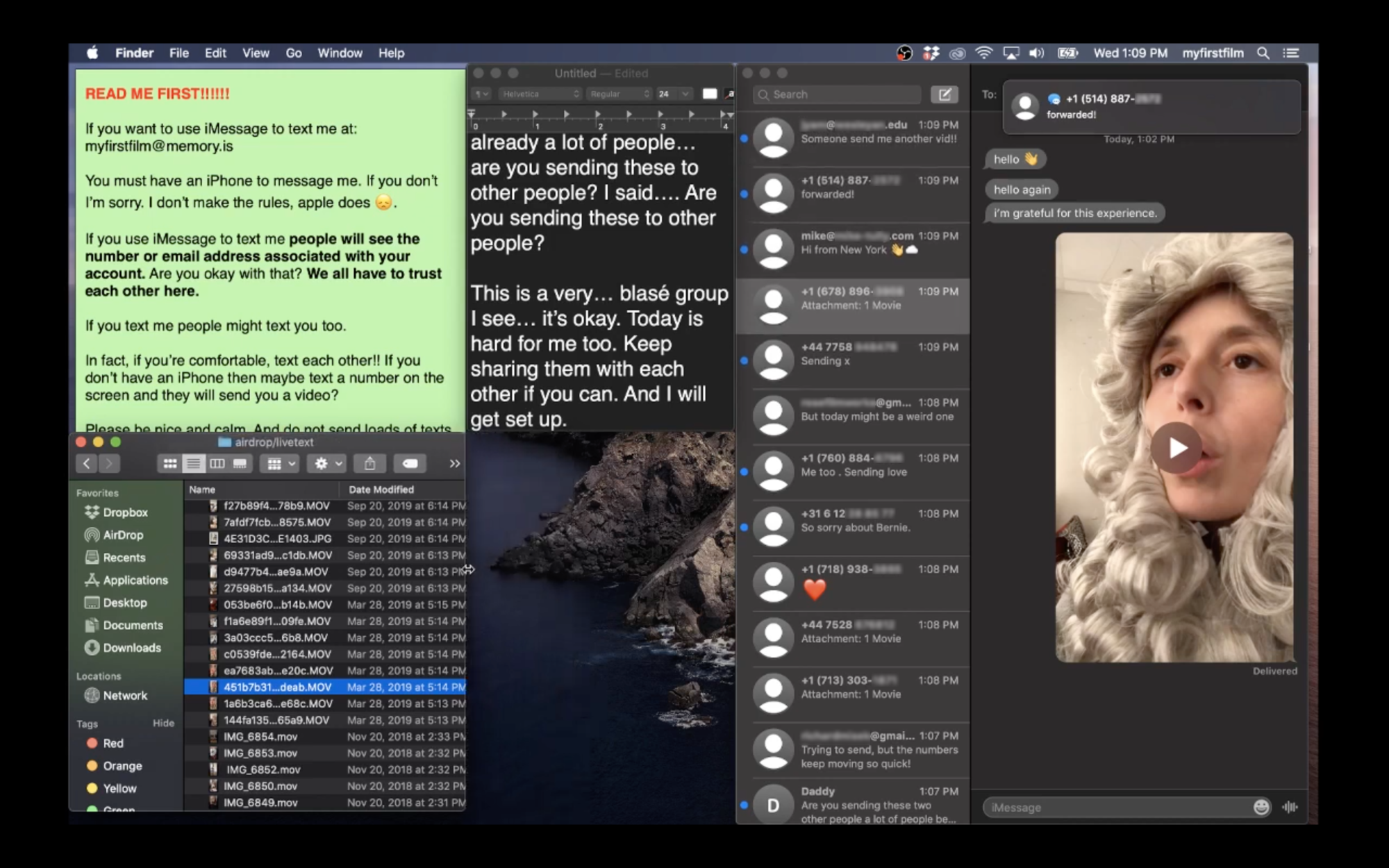

Anger takes the opportunity of online performance to engage as much as possible with the live experience and the audience interaction it allows. Viewers—now untethered from the rules of a theater—are encouraged to use their phones to text Anger at the beginning of the performance to receive a short video clip from the artist. Many viewers text Anger words of encouragement or thanks after particularly emotional moments during the show.

The live broadcast of Anger’s computer screen also serves as a small window into her everyday life: you see iMessage threads from family members and notifications reminding her to do mundane tasks. She turns on the Do Not Disturb feature halfway through the show, but these unintentional, small intimacies are a perfect complement to the heavy content elsewhere on screen.

Zia Anger, My First Film (screenshot), 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

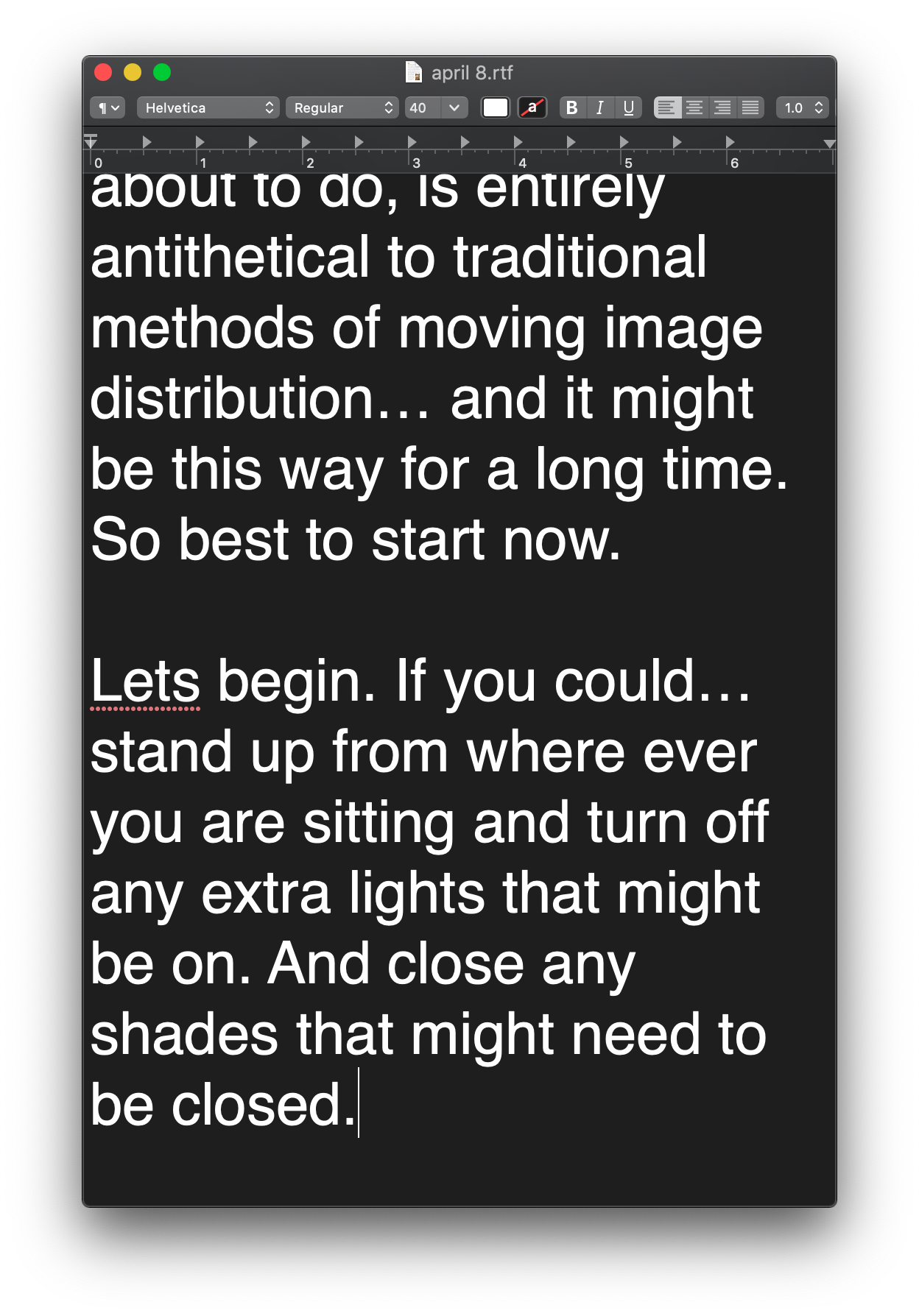

An undercurrent of urgency exists in Anger’s quick shift from in-person performances to an online presentation. When human contact is unavailable, discovering a way to share work is not only difficult but can also incite a sense of mourning for communities that disappeared, seemingly overnight. Anger acknowledges this struggle as she introduces herself to her audience via TextEdit. She describes these screenings as “antithetical to traditional methods of moving image distribution … and it might be this way for a long time.” This prospect is certainly a terrifying one to consider, but it’s not nearly as daunting to hear from a performer and filmmaker as skillfully adaptable as Anger. My First Film demonstrates how distanced viewing on the Internet can offer a chance for wild growth in a new world, not just a temporary obstacle to overcome.

Zia Anger, My First Film (screenshot), 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

Zia Anger, My First Film (screenshot), 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

My First Film’s use of technology on its own is innovative, but what makes it a singular experience as both performance and film is how it redefines and shapes what storytelling could look like in our era. Now more than ever, we use new media to shape our identities in real time, often to catastrophic extremes. We accept this superficiality and use it to hold our online worlds at arm’s length, just far enough away to say that this is not real. Quarantined and distant, the Internet is now our primary way to connect with others. Expectations have been laid low, and we have come to the startling conclusion that there is reality in our performances and that the Internet is in fact real life.

All of that stated, My First Film is not a morality tale against online artifice. Instead, Anger understands that contemporary performance and concealment are aided by her chosen artistic medium, and so much value can be gleaned from our daily performances—regardless of whether they align with our actual selves. Interpreting Anger’s story of family, loss, and womanhood as simply confessional undermines her agency as an artist and person. Too often we see excavations of women’s lives reduced to a one-dimensional understanding of “truth” and “fiction,” instead of allowing for analysis of the performative mythmaking and magical realism that happens in between. Fuck the truth: value and deep meaning reside in the stories we tell, transcending the confines of fact and fiction.

Zia Anger, My First Film (screenshot), 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

The viewer witnesses numerous performances in My First Film, all of them critical to understanding Anger’s growth. There is the live performance of present-day Zia Anger, a filmmaker made wiser by the trauma of her youth. There is also the performance of a younger Zia Anger created through the complicated relationship between actor and director, driven by the filmmaker’s clashing attraction and repulsion to the autobiographical element of Gray. There are even small performances nested inside others, illustrated in a clip of Anger that she used as a fundraising update for Gray’s Indiegogo page. The young woman in that video is pallid and anxious, straining to appear competent.

Anger says in her performance of My First Film that she feels sadness and rage toward that version of herself—a young filmmaker who is, according to Anger, high on Adderall, and ready to compromise her vision and ideals to complete her project. Therein lies the contradiction and brilliance of My First Film: Anger may be performing, but these performances do real work in the real world. There is actual truth in Anger’s performance(s), and in Gray, that has nothing to do with the actual content of her story.

Anger never lies or embellishes her events but instead shifts between dramaturgical devices, reality, and avoidance. She has practical reasons for these choices, considering that her story wraps around the health and privacy of loved ones.

Zia Anger, My First Film (screenshot), 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

Anger reveals herself to be even more in control of her performance, knowing the value of revealing and retreating in equal measure. “Sometimes fiction feels more like reality than reality ever could,” Anger told me. “The further away I’ve gotten from certain events in my life, the better I’ve been able to reflect on them and craft something that feels the most like the experiences I’ve had. So, in a sense, yes, it is truly autobiographical even if it is not one hundred percent [divulging] of every personal detail.”

Zia Anger, My First Film (screenshot), 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

There are moments in My First Film, and in particular Gray, that dip further into fiction, setting up a shocking juxtaposition between magical realism and lived experience. One particularly striking example: Anger shows the slow lead-up to Gray’s sex scene—the one that will presumably lead to the main character’s pregnancy. We see a clip of this young woman passively listening to music at a concert and catching the eye of a man. The two leave the venue and go to the woods. Anger closes the iMovie window before the two have sex, leaving the physically intimate moment to the viewers’ imagination. Later in My First Film, Anger shows Gray’s surreal birthing scene, in which the protagonist is alone in a woodland cabin, convulsing with labor pains. The young woman leaves the cabin and gives birth, but instead of an infant, she delivers her own doppelgänger. The mythic birth leads to Anger sharing multiple possible stories about how she was born and conceived, never quite revealing to the audience how it actually happened. Through Gray’s central pregnancy and the various pregnancy stories, Anger gets to talk about her abortions that occurred during the film’s production. The discussion is emotionally vulnerable and brief, but the juxtaposition Anger sets up through these various pregnancy stories gives her the freedom to explore her abortions on her own terms. In the space between My First Film’s performative telling of lived experience and the plot of Gray, the emotional center of a woman’s bodily autonomy gets precedence—still too much of a rarity in filmmaking.

Zia Anger may be right: Gray might have been a film not worth seeing or releasing. But Anger undeniably is among the most talented filmmakers working today and is capable of making searing work that eschews traditional memoir to reveal a more honest interpretation of life as an artist. With this film, once caught in purgatory, Anger has reconfigured what performance and mythmaking can look like in this digital and distant era. My First Film warrants watching and rewatching, and it reinforces the idea that how we tell stories matters more than the content of the stories themselves.

***

This review originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Summer 2020 // Living & Working.