Tariku Shiferaw

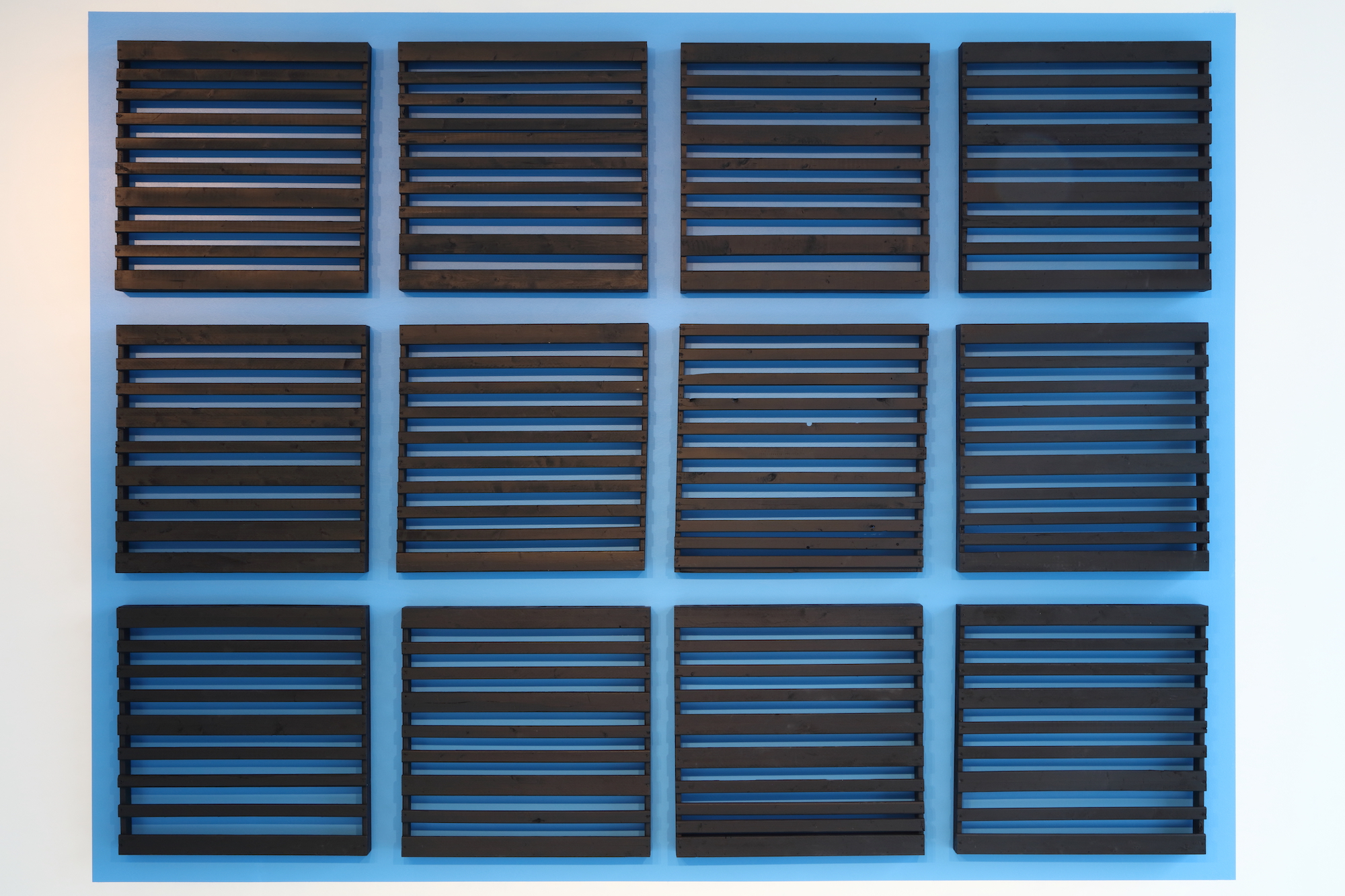

Tariku Shiferaw, A Boy Is A Gun (Tyler the Creator), 2020 [photo: Mike Jensen; courtesy of the artist and the Zuckerman Museum of Art, Kennesaw]

Share:

Conceptual artist Chloe Bass has asked “is abstraction or directness more likely to afford us the understanding we need to move forward?” Contextualized within the tumultuous political backdrop of the contemporary moment, Bass questions whether abstraction, as a mode of artistic production, possesses the urgency and clarity to deliver messages that cannot be ignored. Bass’s musings spark the question: what does artistic production look like in the wake of a new civil rights movement, and how are 21st–century artists responding to an era of daunting precarity?

In curating the exhibition UNBOUND at the Zuckerman Museum of Art, I critically considered the ways Black artists have used abstraction to contend with their times, and how they transformed a formalist language to respond to social and political concerns. Included in this exhibition is New York–based artist Tariku Shiferaw. Unabashedly confronting issues related to racial identity, Shiferaw employs an obstinately formalist language of geometric abstraction in his practice to unpack the precariousness of contemporary Black life and celebrate the cultural production of Black people. In his work, Shiferaw makes use of geometric forms, ambiguous marks, and a limited color palette of mostly black and blue.

Tariku Shiferaw, A Better Tomorrow (Wu-Tang), 2018 [photo: Mike Jensen; courtesy of the artist and the Zuckerman Museum of Art, Kennesaw]

In his installation A Boy Is a Gun (Tyler, The Creator) (2020) Shiferaw explores the dichotomy between the colors black and blue, and their multiple and varied connotations. The work consists of 12 black, wooden forms that echo the structure of shipping pallets, placed on top of a cerulean blue surface. Shiferaw relies on the openness of abstract language to subtly reference through hues the relationship between Black bodies and blue uniforms, the melancholic sounds of the blues, the blue–collar workforce, and the black and blue of bruised skin. Shiferaw’s work hinges on the multiplicity of meaning that can be drawn from a simple color or a single form.

Horizontal bars, which recur in much of Shiferaw’s work, can be understood as symbolizing censorship and blockage. Shiferaw conceptualizes these bars as a deconstructed X, however, and uses them to mark space—the physical space of the canvas, and a metaphorical space within the history of abstraction. Shiferaw’s work nods to midcentury abstraction, but he also marks this minimalist, formal vocabulary with references to Black popular culture. He weaves historical and contemporary narratives together by referencing hip-hop, R&B, blues, and jazz—musical genres that originated in black communities—in his titles. His work is visually situated in ambiguity, but by referencing music, Shiferaw adds an extra layer of meaning and provides a lens through which to understand his work. The comprehension of his work—in full—is contingent upon engaging the cultural production of Black artists, musicians, and composers. Shiferaw embeds politics and a celebration of Black culture within his formalist aesthetic such that the work’s meaning flows through and beyond the visual.

Tariku Shiferaw, Ivy (Frank Ocean), 2020 [photo: Mike Jensen; courtesy of the artist and the Zuckerman Museum of Art, Kennesaw]

Tariku Shiferaw, Mad (Solange), 2020 [photo: Mike Jensen; courtesy of the artist and the Zuckerman Museum of Art, Kennesaw]

Nzinga Simmons is an art historian, writer, and curator based in Atlanta. She is currently a Tina Dunkley Curatorial Fellow in American Art at the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum. She received a BA in art history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with a focus on works of art from Africa and the African Diaspora. Through her writing and curatorial practice, she aims to highlight the significant contributions of often marginalized artists to the canon of American art.