Tania El Khoury: Where No Walls Remain

Tania El Khoury, As Far As My Fingertips Take Me, 2016 [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Lebanese-British artist Tania El Khoury and I met when the Fusebox Festival curatorial team, of which I was a member, invited her to present her performance piece As Far As My Fingertips Take Me in 2018. The US was, and still is, engaged in an intense debate over the proposed building of an enormous wall—meant to keep immigrants out—along our Southern border. El Khoury’s work asked: What if you could sit right next to a wall and hear the real story of a refugee sitting on the other side? The realities of human displacement and forced migration can sometimes feel abstract when reported from screens and front pages. In As Far As My Fingertips Take Me, these realities arrive home with a conversation between an audience member and a refugee. Although separated by a wall, both participants are nonetheless intimately present. This vivid telling of the refugee’s story resonated in Austin, TX, a city known for its liberal values, but also the capital of a border state at the center of an immigration crisis, where multiple detention centers for adults and children are in close proximity, and the border with Mexico is just over 200 miles away.

El Khoury’s work is focused on migration, borders, and the ethics and politics of these encounters. She has staged performances and installations at the edges of an ocean, on the street, and in theaters, museums, and galleries internationally. El Khoury is co-founder, with architect and planner Abir Saksouk, of the interdisciplinary research and performance collective Dictaphone Group, which produces site-specific performances that redefine our relationship to urban spaces. El Khoury was the 2017 winner of the ANTI Festival International Prize for Live Art, and she is a 2019 Soros Arts Fellow. This past year, she was also the subject of the retrospective ear-whispered: works by Tania El Khoury, presented by Bryn Mawr College and FringeArts. Recently, I had the chance to speak to El Khoury via Skype about her work to date, and what it means to cross borders in her art and life.

Anna Gallagher-Ross: Tania, thank so much for talking to me today. You are based between Beirut and London. How has the experience of living between these two places shaped your practice?

Tania El Khoury: You know, I’m still very much living between places, and recently spending more time in the US, so it’s hard for me to look with a distance at how this may have affected me and my work. I guess both positively and negatively. But I’m a passionate traveler; I think—or joke— that I was a nomad in a past life. I get bored from being too comfortable in one place and constantly need to move on. London has allowed me to survive as an artist in a way that I wouldn’t be able to do in Lebanon, because however difficult it might be to make a living as an artist in a huge city that is overpopulated with artists, as it is in London, it is still much easier to do that there than in Lebanon, where there is [very limited and often inaccessible] public funding in the arts. Also I think the art scene in Beirut is—even though it is very lively—either theater or visual arts. There is no space for live art and performance that does something on its own and is not just a version of contemporary theater. I actually see this issue in the US as well, where performance is understood as just theater, but that’s another story that we could talk about at another time.

AGR: We need a whole other interview for that one.

TEK: One way that I’ve worked as I’ve shifted between the two places is that I focused my work in Lebanon on site-specific performances in collaboration with an urbanist as part of the Dictaphone Group collective. I was touring my solo work elsewhere in the world, because I felt that it was more urgent to work on public spaces while in Lebanon and produce that kind of knowledge rather than showing my tourable pieces.

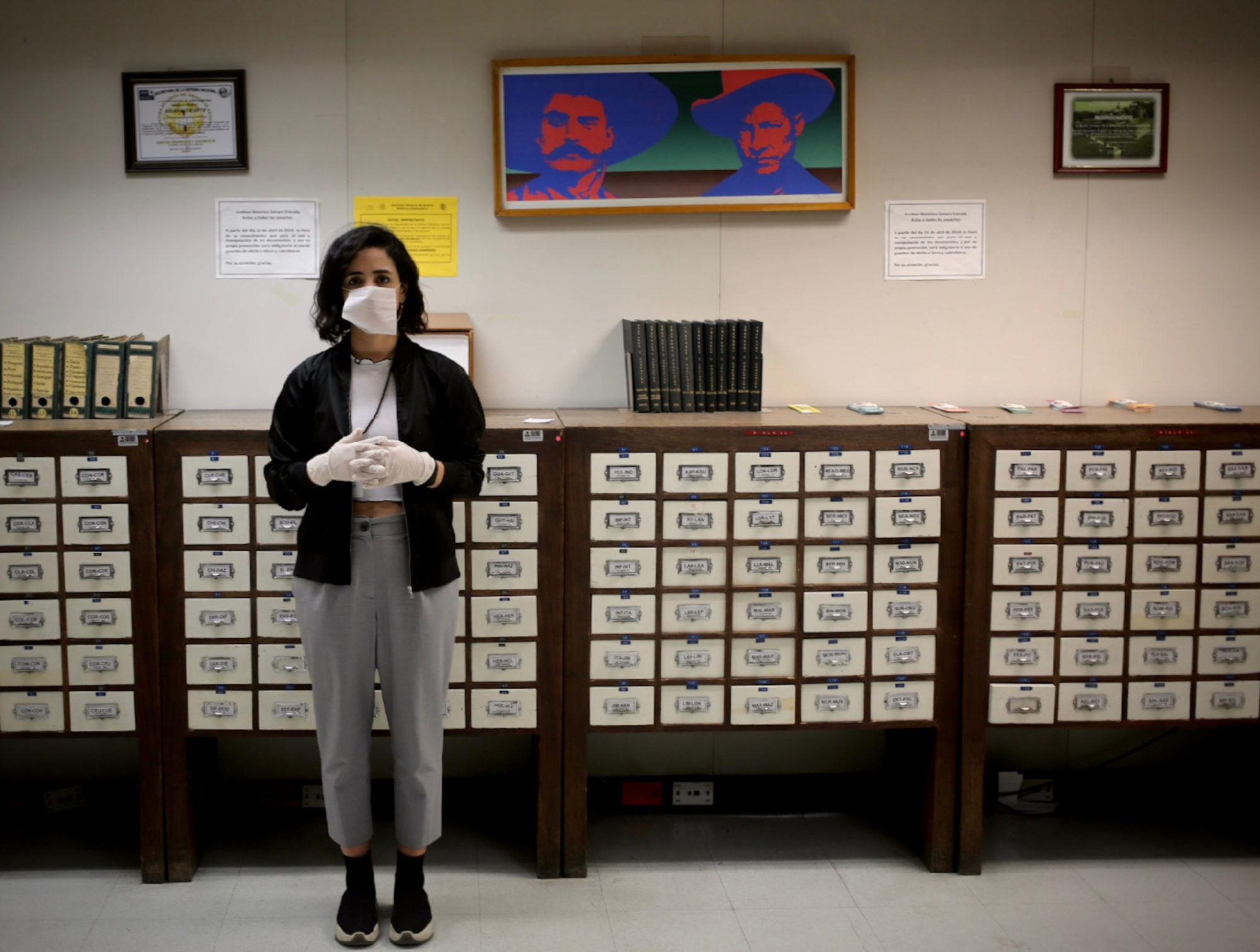

Tania El Khoury, The Search for Power, 2018 [photo: Elina Giounanli; courtesy of the artist]

AGR: And for your recent work—which is about Lebanon—The Search for Power, you delved into the history of power outages in the country, and this led you to archives in Belgium, France, United Kingdom, and the US. Could you talk about what you found there, and the darker legacy that was revealed by this history of electricity?

TEK: I don’t want to reveal too much about the piece, as it is still relatively new and I want people to go see it … but what’s not surprising for anyone is that the story of electricity blackouts in Lebanon is not just about a dysfunctional public utility, but about economic and state power. It was also very striking to understand the involvement of many colonial and imperial powers in the history of electricity, because at the time it was a very profitable business. Just like how oil is right now, electricity affected policies and politics and diplomacy.

AGR: Since your collaborations with Dictaphone Group, you have always been interested in archives and what they reveal. I think about the state-sanctioned archives that you’ve looked at, and in contrast you produce these kind of alternative archives, whether oral histories or photo or video documentation. Could you say more about the relationship of the archive to power in general in your work?

TEK: I think about my work as producing knowledge that can contribute at a later point to an archive, but at the moment it’s concerned with the conversations that are happening right now in politics. You can say that my work poses questions on the accessibility of this information that affects our daily life. For example, who owns the seashore in Lebanon, and why is public access to the beach barely existent? In the case of The Search for Power, I worked on it with my husband, Ziad Abu-Rish, who is a historian. We started by researching electricity in Lebanon, and we couldn’t find much that told us why we have electricity blackouts. Access to information is very difficult, so we needed to look elsewhere. We started with World Bank documents and moved on to the archives of foreign embassies and so on. Oral histories, like the ones I use in Gardens Speak, will become a historical document that archives the first period of the Syrian Uprising through the lives and deaths of these ordinary people who were killed by the Syrian regime. These types of stories are very important when you have a regime that tries to erase its population, both figuratively and practically, and an international community that frankly doesn’t give a fuck about Syrian people and is only concerned with geopolitical discourse.

Tania El Khoury, As Far As My Fingertips Take Me, 2016 [photo: Nada Zgank; courtesy of the artist]

AGR: I think it’s vital, those archives that you are producing. In your work, the borders that separate us—whether visible or invisible—are often the subject, and yet in presenting these eye-opening stories about separation and state suppression, you also include the audience. What are the various ways you involve the audience in your work?

TEK: I always involve the audience. Not just when I work on borders, though one could argue that all my work has been about borders in a way. I see interactivity as an artistic form by itself, an aesthetic and political choice, and I’m not ready to move towards a more passive spectatorship. The audience is never just an audience, but is always part of the story, a political being, a collective, but also a complex individual. And I’m interested in how interactivity allows for each performance to be totally different, rather than just having one endless run of the same show every night to an audience sitting in the dark, or to have viewers as just anonymous entities. I like the intimacy of small audiences. I like how vulnerable this makes the art, the artist, the audience, and the performer.

AGR: Could you say more about your use of the word “interactivity”? In performance, there are always these conversations about participation, and I really appreciate your choice to use the word “interactivity” here.

TEK: Yeah, I step away from the word “participation” because it reminds me of participatory politics, participatory architecture, participatory policies, and these labels are often used to mislead communities into thinking that they have choices, when these choices were already made for them by people in power. And in certain cases, when it’s used in performance, communities where these performances are made and researched and performed are called “participating communities” by the artist. I often wonder, who is participating here? Is it the artist allowing these communities to participate in an artwork about them? Or should it be, these communities are allowing that artist to participate in their lives and their everyday politics? I think “participation” is quite misleading and has been abused as a word. I find “interactivity” to be more suitable for the ethics that I strive for in my work.

Tania El Khoury, Gardens Speak, 2014 [courtesy of the artist]

AGR: Speaking of interactivity, I’m thinking about multisensory sensations and the way that’s employed in your work. In Gardens Speak, the audience touches and smells the soil in the experience of the stories told. In As Far As My Fingertips Take Me they give their hand to a refugee they can’t see on the other side of a wall who tells their story of displacement and migration, while marking that story in ink on the audience member’s arm. Could you talk about the impact of these sensory textures on the storytelling in your work?

TEK: I don’t like to talk about impact on an audience, to be honest. I feel like it’s a nonquantifiable notion, and it also risks glorifying both the artwork and the artist. But think about the political potential of interactivity— as you said, it involves all senses and the body, so it’s not just about rationalizing the content of these pieces, but about experiencing it; listening as a radical act, sensing, embodying, et cetera. This allows for a deeper connection with the work that goes beyond just the rational, the intellectual, and it’s not just emotional either, nor entirely spiritual. Maybe it’s somewhere in between all of that … and I personally find it exciting.

AGR: To shift a little bit—your work has been translated into multiple languages, and toured 32 countries across the continents. Could you talk about things that were lost or found in translation in presenting your work in different geographical locations?

TEK: I actually like it when pieces are translated into different languages, because people tend to think of English-speaking performances as not translatable, which is not the case. In my case, English is my third language, and I don’t love it, to be honest. When I perform in English, people don’t think of it as a translation. But when it’s in Italian or Greek, they start to think of it as a translation. And obviously we can talk about Americanism as a dominant culture, but the use of language is always political. For example, I don’t present work in Lebanon or in the Arab world in English, because that’s just telling local populations that the work is an elitist event. And when pieces can be easily translated—like Gardens Speak, because it’s mainly sound pieces—I prefer that they are presented in the local language, rather than English, because English in Gardens Speak is a translation from Arabic anyway. I feel that doing so brings it closer to people who are experiencing the work. There are obviously concerns about how things are translated when they are in languages I don’t read or understand, so I try to work with people I trust and pay attention to who are performing the pieces in other languages. For example, is the French version performed by a voice that sounds like a middle-class or upper-class white man? Or does it sound like it’s performed by a person who’s bilingual and is from the banlieue for example. It’s a big difference.

Tania El Khoury, Cultural Exchange Rate, 2019 [photo: Ziad Abu-Rish; courtesy of the artist]

AGR: I’m thinking about translation of language, but I’m also just thinking of communicating the work in different geographical locations, and I’m thinking of geographical locations that have a close proximity to borders, and some that are very remote. Are there instances in which the work reads in a different way in each of those specific locations?

TEK: I think at the moment, borders affect the whole world. If I was performing this piece in Australia, some might assume that most audience would be privileged with an Australian passport. But this is also a settler colonialist country, where the state has historically exercised borders on indigenous communities through the policies of White Australia, and through Manus Island, an open-air prison, forcing refugees into actual suicide. I can’t think of anywhere in the world right now that is completely unaffected, in its own policies or histories, by borders as a social and political construct.

AGR: Borders have occasionally become an obstacle to your work being seen. I wonder if you could talk about your experience in touring the work internationally?

TEK: I’m privileged in that I have dual citizenship. I’ve experienced traveling or touring my work on a Lebanese passport, versus when I started touring on a British passport, and it is like day and night. I’m aware of the hassle that artists from the global South in general have to deal with, sometimes barely supported by the inviting venues or countries, and they end up having to fill out forms by themselves, pay visa fees, deal with bureaucracy and anxiety, and many times get rejected. I have many stories, some of which you know, about collaborators who got refused visas recently. We responded to this particular discrimination through the work, so the story [of visa struggle] became part of the work itself, and in a way, allowed us to open up conversation about border discrimination. I think the art world needs to be discussing more practical ways of dealing with how many artists get visa rejections. I’m not going to mention specific cases that happened to us because some of these collaborators are currently in the process of applying for another visa, and I don’t want to affect that.

Tania El Khoury, Cultural Exchange Rate, 2019 [photo: Ali Beidoun; courtesy of the artist]

AGR: Of course. So, you are co-curating the biennial of contemporary performance at Live Arts Bard called Where No Wall Remains. Could you tell us a bit about this project?

TEK: Excitingly, it’s my very first time curating other artists, and it has been brilliant. I get to choose people I find inspiring, learn about their process, give them a commission opportunity, and, as an artist, situate my work within their work and in conversation with them. It’s been really fun. It was an invitation by Bard College’s Fisher Center for the Performing Arts. I was invited by the Artistic Director for Theater and Dance, Gideon Lester, who co-curated the festival with me, and we dreamt of a festival across continents that would happen in New York, Berlin, and East Jerusalem, and how these three different cities have a different relationship to border walls. At the moment we are still dreaming of this, but for now in November, it will be a four-day festival in New York at the Fisher Center and some places nearby, like the Bard Farm and the restaurant Murray’s in the nearby village of Tivoli. It will be a program of commissioned pieces, which I find unique in festivals and special because it is not just about curating hit pieces, but about curating artists and trusting their abilities and process. The works will be different and multidisciplinary, some are interactive, and others are not. A number of them will include live music; others will include dining or farming. It’s a beautiful mix of mediums, ideas and practices. The common ground is that these works respond, in one way or another, to the notion of borders.

AGR: Could you mention a few of the artists involved?

TEK: Yeah, so, we will have: Palestine Hosting Society; Emilio Rojas, Basel Abbas, Ruanne Abou-Rahme, and Muqata’a [Tashweesh]; Emily Jacir; Jason de León; Rudi Goblen; Ali Chahrour; and me.

AGR: This will be the US premiere of your work Cultural Exchange Rate at the biennial, and it tells the story of a hundred years of border crossings by your family. Could you say a little about how this work came into being?

TEK: This work has been coming into being for ten years. I’ve collected random material from my family’s relationship to border crossing and migration, but have never done anything meaningful with them until now. So, I’m very excited to share it with the world finally. It will be an interactive piece in which the audience is the main activator. The piece contains ten different scenes or images or stories that will be experienced by each audience in a different order. The narrative of the piece is a sort of puzzle, which is very much how I’ve collected these stories—in a scattered way. Again, I don’t want to ruin it for people who might experience it, but I’m terribly excited and terrified about this work, because it’s quite personal. I also think it is global, politically speaking. But let’s see what people get out of it.

Anna Gallagher-Ross is associate artistic director & curator at Fusebox, an annual contemporary performance festival based in Austin, TX. A graduate of the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, she has curated performances, exhibitions, and public programs in New York, London, Toronto, and Austin. Her writing and interviews have appeared in C Magazine, Walker Reader, Theater, Written & Spoken, and elsewhere. She is co-editor of Imagined Theatres, Issue #04: Curating Performance (fall 2020).

Tania El Khoury is a live artist creating installations and performances focused on audience interactivity and concerned with the ethical and political potential of such encounters. Her work has been translated and presented in multiple languages across six continents. She is a 2019 Soros Arts Fellow and the recipient of the ANTI Festival International Prize for Live Art, a Total Theatre Award, and the Arches’ Brick Award. El Khoury holds a PhD in performance studies from Royal Holloway, University of London. She is the co-founder of the urban research and performance collective Dictaphone Group in Lebanon.