Szu-Han Ho: COVID–19, the #PPE we all need

Szu-Han Ho, Shelter in Place, 2016 [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

This conversation is one of several that I undertook with artists from late April through early May 2020. People were still adjusting to self-quarantine, social distancing, working from home, or losing their jobs. In early May the world was already changing incomprehensibly from one week to the next. The passage of three weeks brought video of another Black man, George Floyd, being killed at the hands of police, which jettisoned the US into widespread civil unrest and public protest. This interview documents one moment of art making in a radically changing world. — Joey Orr

***

Who is making art when so many of us are stepping back from our usual ways of inhabiting the world? When museums and other exhibition venues are closed, where do we go to hear artistic contributions to such a polarized moment in public discourse, when the protection of our very lives is being instrumentalized for bad politics? In many ways, flipping through Instagram has been taking the place of studio visits in our time of social distancing. During my search for artists taking on the precariousness of this moment, I found Szu-Han Ho’s imagined personal protective equipment (PPE) that lends a delicate but incisive tone to the longing for closeness we all feel now.

The subject of the series is the one thing not represented in the work and precisely what cannot be realized in a time of self-quarantine: our touching bodies. Through sketches of protective gear for our new world, however, Ho addresses not only the immediate yearning for physical contact but also how this need is symptomatic of something deeper that has become increasingly explicit. Our urgent need for acknowledging and acting on our shared and perilous fate has been compromised by institutions that have been failing us for some time. The vulnerable are made more vulnerable, to the point of rupture, and our global interconnectedness is sacrificed again and again at the cost of our lives and the planet we inhabit. Emerging from simultaneous impulses toward despair and hope, Ho shares her thoughts about making, activism, immigration, and ecology.

Joey Orr: Your installation and performance piece Shelter in Place, was realized in 2016. Although the work addresses a very different history and context, it is thinking about the idea of shelter through material and performance. Your series COVID 19 the #PPE we all need seems related in that sense. Have you thought about the return of sheltering in your work now?

Szu-Han Ho, Shelter in Place, 2016 [courtesy of the artist]

Szu-Han Ho: I do see a strong connection between Shelter in Place (2016) and this current series. Shelter in Place comes out of my understanding of crisis—how I’ve survived it, how my family has survived it, and how so many contradictions emerge from the surviving: the feeling of dissonance I get from experiencing great loss as well as profound beauty and resilience. It’s a very confusing and paradoxical thing. The actual sculptural form of the piece is also meant to conjure that ambiguity through the suggestion of many possible objects/spaces: a shelter, a ruin, a monument.

I started making this current series, of course, under the stay-at-home order. I know some elected officials have opted to stay away from the phrase “shelter in place” because of the connotation of mass shootings and wartime. With the current situation [still under the stay-at-home order as of this interview], I’ve been thinking a lot about how the things that keep us safe right now—the social distancing, the protective gear—are also what deprive of us of really essential things: physical touch and intimacy. I’m really feeling the loss of those things right now. I can’t think of a time when I’ve gone this long without physical contact from another person. I also feel that sense of contradiction every time I listen to or read the news: I’m hearing about this thing that we’re all going through in some shape or form, and that helps me to feel connected to the world in a bizarre way, but it’s also creating more anxiety, unease, and disconnection.

JO: Although your studies for protective gear underscore our inability to physically touch each other now, by preparing the plans for their function and construction, they evoke a very real longing for human contact, as you suggest. They protect, but their necessity reproduces an ache for something we miss. Is this moment of sheltering in place and self-quarantine connected to an already existing politic that is simply made explicitly manifest now?

S-HH: As with all major social crises, I think this one has brought out the … dynamics bubbling under the surface. And we are definitely seeing systems and institutions imploding all around us, systems that have been failing many people for a long time now but are doing so at such a breathtaking scale. In general, we live within systems that drive us apart from one another and mediate/distort our relationships. It is strange, isn’t it, that the right thing to do right now (in terms of public health) amplifies that isolation?

And the conundrum is also there in the ways that we try to remain connected, through digital media …. It’s the lifeline that can also be the noose. I was trying to find a way, through these drawings, to actually create connection—or the imagined possibility of it—in a material, nondigital way. I could really use a hug right now, and this is one way to imagine connecting with someone that isn’t dependent on Zoom.

I wanted to make these [drawings] very quickly, to give them immediacy. The fact that they are plans for something feels important. As soon as I made the first one for hugging, I thought, yes, I really need this to exist in the world! There’s a satisfaction that comes from being able to make these very quick studies; they’re sketches for the planning of something embodied. Then I very quickly go back to the longing that they emerge from.

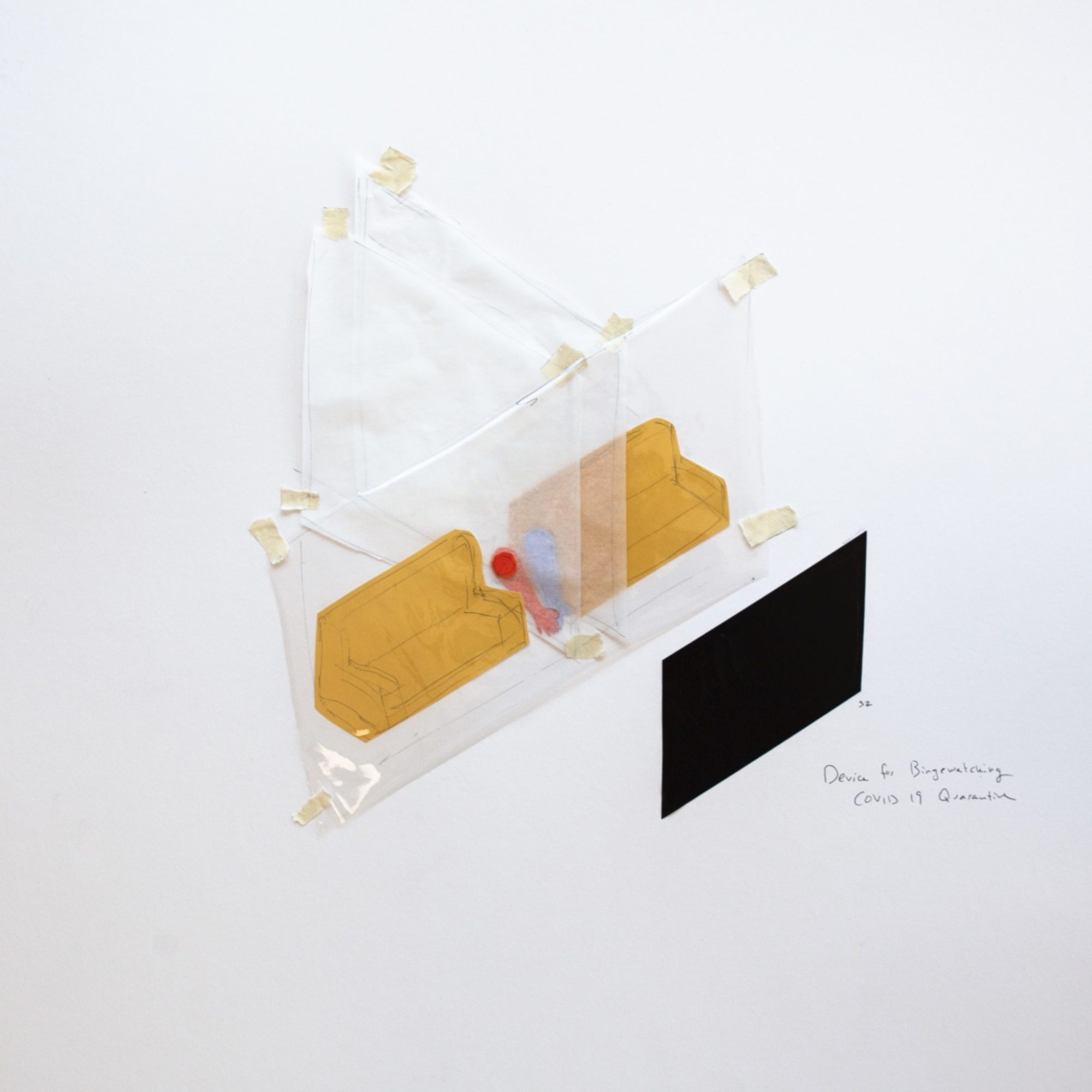

JO: Device for Grabbing a Drink (Sonic Projection Dishes) and Device for Bingewatching seem to have a more humorous tone. Actually, the sonic projection dishes are not just imaginative, but could be a really effective idea for right now. Of course the rub is that you would never be facing each other. And the little arm extensions in the PPE for bingewatching make it so you could hold hands while streaming a series about one of our many imagined dystopian futures. They are too delicate to be jokes, though. They are more like a subtle and kind nod of acknowledgment over a shared understanding. Can you say something about gently teasing a knowing smile out of the viewer, or just about the gentleness of the work in general? Even the materials and palette seem gentle to me.

S-HH: Since I wanted these to be studies, I wanted them to feel temporary, contingent. And also tender. I was dreaming up these elaborate ways to actually make these intimate gestures possible, and because I’ve also been making masks and reading obsessively about best practices for preventing spread of the coronavirus, I really took the safety part seriously. So the design of the devices started to feel more and more complicated for these simple acts of togetherness. For some reason, the Device for Bingewatching took me awhile to conceive, even though it was one of the earlier urges. It’s not that easy to devise a way to share space, sound, and image with someone while protecting [each other].

JO: You are part of the New Mexico Craft Responders, which seems like an activist treatment of this same subject matter. Can you tell us about the group’s work?

S-HH: My projects sometimes split in this way: there’s the “activist” work that is pragmatic, and then there’s the “art.” There’s always going to be the part of me that feels that something urgently needs to be done, but as we know, change comes very painfully or sometimes not at all. So I have to make something into art to actually remember that transformation (or even transcendence) is possible. Sometimes I need a clear distinction between the two—artmaking and organizing—and other times they collide. The process of collision can be gratifying in its own right, regardless of whether we get to the outcome we’re struggling towards. Hopefully, that progress does eventually come along, but I think you have to be a superhuman … to withstand the disappointment and heartache of movement building if there’s no joy or beauty in the process.

Szu-Han Ho, NO, 2018-ongoing [courtesy of the artist]

S-HH (cont.): NM Craft Responders is a collective of artists, makers, and organizers that sprung from the COVID-19 pandemic. We feel that this particular group of people—artists, makers, and organizers—are incredibly resourceful and can mobilize quickly. We started by making masks and intubation boxes that were requested by hospitals and healthcare workers. We’re now also making masks for other frontline workers and vulnerable members of our community, and we’re allied with other amazing local maker groups. I’ve been really struck by how, even with layoffs and real financial hardship, people have been committed to giving their time and energy and money to this. Seeing how these kinds of mutual aid groups have sprung up all over the globe has been truly life-giving in these grim and scary times. The organizing piece of this is something I have personally learned a ton from, and I hope we will carry it with us way beyond this current crisis. I guess you could say that the #PPE we all need drawings are the flip side of this effort to fulfill a direct and urgent need of the masks—but for me, these drawings represent just as urgent of a need: the need for intimate connection.

JO: Just looking back here and seeing a lot of co-existence among contradictory experiences: loss and resilience with sheltering in place, heartache and joy in movement-building, connection and anxiety while staying informed. You also say that art making reminds you that transformation is possible, but of course the artistic making is evoked by these very contradictions. Are these dynamics the condition of your artistic making?

S-HH: Yes, I think that tension is always the seed of a project for me: something that catches me off guard and makes me feel an inherent friction. That’s the way I approach working with materials. For example, I’ve used Mylar emergency blankets in different ways, because they have come to represent the inhumanity and cruelty of the U.S. immigration detention system, but they have also been appropriated by protestors to call out that cruelty. And it’s this shiny, flashy material. So all of that generates ideas and feelings, and becomes something new for me through a project: I used the emergency blanket to make choir robes for MIGRANT SONGS, and in NO, I designed what I call a “multi-functional garment for the migrant justice movement,” in which this piece can be used as a banner, a poncho, a shade structure, and a supply tote.

Szu-Han Ho, Migrant Songs, 2019 [courtesy of the artist]

JO: So much of your art and protest work is invested in immigration. It seemed like a human rights issue that continuously exceeded its previous boiling point, beyond all belief. We hear so little about it in the mainstream media now since COVID-19. How do you connect our immigration crisis with the pandemic and our ecological crisis?

S-HH: We are seeing that immigrants are amongst the most vulnerable in both of these crises: immigrants make up a huge part of the farm workers, the meat plant workers, healthcare workers, much of the frontline essential workforce. And migration itself is tied up with the ecological crisis, as more people are being displaced from their home countries due to climate change. Migrants seeking asylum are unnecessarily being held in detention centers, which are highly prone to outbreaks—putting so many lives at risk. Immigrants and “foreigners” once again become scapegoats, linked to the introduction of disease and physically and verbally attacked because of it. Before the CDC recommendation came out, for weeks, I was worried about wearing a mask in public for fear of being targeted. I did it anyway, because I thought it was the right thing, but it didn’t stop me from feeling that fear. You see how little it takes for the xenophobia to resurface in this country, in this particular case, against Asians and Asian-Americans. You see it in the disparities in access to accurate COVID information in different immigrant communities, because of language and technology access. You see it in how undocumented immigrants are even more vulnerable, since they are excluded from government relief—from stimulus checks to unemployment benefits, to better healthcare, even though they pay taxes. The pandemic has brought all of these issues to the forefront for immigrant communities, even if you don’t see that reflected in mainstream media coverage. All of this is part of the ongoing struggle of the migrant justice movement, amplified by this crisis. I hope we can all take a breath to think about what ties us to one another, even though we may be feeling isolated.

Szu-Han Ho, Migrant Songs, 2019 [courtesy of the artist]

JO: I have recently been looking at the New Green Real [Carrie Brownstein, Harrell Fletcher, Addee Kim, Eric Johnson Olson, and Salty Xi Jie Ng], a group that [posts] news coverage about how animals, plants, and the planet are beginning to recover in this pause of human activity. They ask this question: “While we collectively hold the global trauma from the COVID-19 pandemic, how can we use the insight gleaned during this time of crisis to reshape our world ecologically?” You are a professor of art and ecology at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. How does this question sit with your own views on ecological justice?

S-HH: I think this pandemic has made it clear that things can’t go back to “normal,” whatever that meant before the crisis. I’m very interested to see how and if people, myself included, will restructure their lives. We know that it’s not enough for individuals to change consumer behavior in order to bring life on this planet back from the brink …. I think that the only way we will bring about the necessary restructuring is through collective re–imagining and uprising: that can happen on the local, neighborhood scale, as we’re seeing with mutual aid projects, all the way up to mass movements [that] demand political, economic, and social change. The pandemic is a manifestation of an ecological crisis; the more feverishly connected we humans are—through trade, travel, migration—the more vulnerable we are. Ecology is all about those interconnections. There have been some beautiful moments that have emerged during quarantining here in New Mexico: I’m hearing more varieties of birdsong; I’m appreciating the transition to spring/summer more microscopically. I am personally prone to abject despair when it comes to the climate crisis, but that is where the art making and organizing come in: at the scale of the people and projects I see around me, I have a lot of hope.

JO: One big motivation for this interview was to bring artists’ voices into public discourse at a time when museums and other exhibitions venues are closed. The tenderness and contingency of this new work emerges from the intersection of contradictory experiences and feelings, and this seems urgent to me now. What do you see artists offering our society and culture in this moment of failed politics?

S-HH: I think a lot of people think of art and culture as something extra, something that is a luxury after all of your “necessities” are met. I disagree. Art, music, and culture are absolute life necessities in my mind. What culture does not have music? What culture does not make art in some shape or form? There’s not a single one without art and music that comes to mind. In this time of quarantine, we rely on artists, makers, writers, musicians, performers, filmmakers, and cultural producers more than ever to bring us together, to keep us at home, to mobilize us, to offer a glimpse of a different reality. I hope everyone comes to realize that and finds a way to support an artist at a time when livelihoods are at stake. Art is essential.

This interview was completed on May 18, 2020, one week before the police killing of George Floyd. I have struggled with whether to release this work. It is one document of my experience of the pandemic, but as the national uprising began, it felt that the world was moving on. These drawings are about my sense of mourning over intimacy and connection with others, with losing contact with other bodies. We are now in a national state of mourning, uprising, and demand for real structural change, and people have taken to the streets in a mass movement, putting their bodies on the line. We self-isolated and stayed home as a matter of public safety, but this moment calls for more. Our bodies have not stopped being the focus: both the pandemic and the uprising have laid bare the huge gulf between the health and safety of some bodies over others. I still don’t know how these drawings will land, what kind of world they will go out into–every day feels like reeling towards a new crisis. No going back may be the only constant. – Szu-Han Ho

***

***

This interview originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Summer 2020 // Living & Working.