Symbolic (Dis)Possession

Photo: Hani Amra

Share:

i. On Symbolic Control

Jerusalem is a city of competing symbols. Specters haunt its present and threaten its future. It is a city caught between Israel’s ideological resurrection of the biblical past and its settler-colonial present. It is an illegally occupied city that seeks to render its Palestinian symbols, and inhabitants, invisible. It is a city that resists stability. It is a city made visible only through its fragmentations.

It is land whose borders have been aggressively re-territorialized since the Nakba, and more aggressively so since Israel’s illegal occupation in 1967. This ongoing process has led to a(n) (im)material violence that hinges on a dialectical process of in/visibility, controlling who has access to Palestinian cities, its images, and its people—how they are seen and heard. In his ethnographic study, Colonial Jerusalem (2014), Thomas Abowd argues that Israeli governing officials understood, early on, “the paramount role that signs and symbols play in naturalizing and normalizing spatial and racial orders of dominance.” Control over the city’s symbolic assets is a crucial part of Israel’s ideological warfare—a violent process that leans heavily on a sacred past to justify the neoliberal advancements radically reordering the city’s urban space.

And it continues, with increasing international buy-in. Trump’s recent decision to move the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem has inaugurated America’s recognition of the city as Israel’s eternal capital, despite international condemnation and Palestinians’ competing rights for East Jerusalem as the capital of their future state. Observers who play down the move as merely symbolic, obscure the history of symbolic and material dispossessions that has robbed Palestinians of the right to their cities. It is no coincidence that little more than a month after the embassy opened in May of this year, Israel adopted a “nation-state law”: racist legislation that cements apartheid by declaring the “state of Israel [a]s the nation-state of the Jewish people, in which it fulfills its natural, religious, and historic right to self-determination,” in turn overlooking its multifaith Palestinian citizens and other minority groups. This law clearly defines Israel’s national symbols but intentionally omits Palestinian assertions of theirs. (As several commentators have noted, the widely spoken Arabic language has been demoted from an official language to a “special status” that will be “regulated by law.”) In addition to actively encouraging settlement expansion as “a national value,” one clause explicitly states: “Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel.” Against this violent tide of history, which has been illegally enacted for decades, Palestinian symbols act as anchors that keep the spirit of a transnational political liberation movement alive.

Photo: Hani Amra

Photo: Hani Amra

As a diasporic Palestinian and a temporary returnee, my relationship to Jerusalem is mediated through my fractured perspective. Since October 2015 I have been declared by Israel persona non grata, an understatement that is apparent only in the term’s translation: person not appreciated. I have been interrogated at borders countless times and subjected to endless racism by Israeli airport and ministry officials for simply trying to return “home.” This treatment has left little doubt as to whether I have ever been “appreciated” by the Israeli state. And yet, in being issued a 10-year ban and locked for hours in a detention center, it clearly wasn’t a case of being underappreciated. I was arbitrarily and unambiguously criminalized for how I look and for the Arabness of my name. For Israel, image matters. This was confirmed by the Ministry of Interior official who, upon signing my deportation letter, threateningly told me: “From now you will only see Israel through the image. Do you understand?” His careful choice of words was an unnerving insight into how Israel’s colonial optics seek to control the image, at home and abroad.

With my now-forced distance from Palestine, which began with my maternal and paternal grandparents during the Palestinian Nakba (catastrophe) of 1948, I remain haunted by the fragmented images and memories I attach to its cities—a haunting, that compels me to disentangle the visualization of power that works to distort Palestinian reality.

ii. An Attempt at Symbolic Reclamation

Preserving our symbols, whether physical or virtual, from misappropriation or invisibility becomes a highly political act. Yet, as my encounter with the brutish officers at Israeli-controlled borders taught me, it is not always a process that can be enacted or articulated. In the story that follows—which begins in and ends on a reflection upon Jerusalem—I was able to consider the pernicious ways in which icons of persons oppressed beyond Palestine are being politically and economically dispossessed. It is a reflection born of coincidence that links two seemingly disparate icons of resistance: Tupac Shakur and the site Haram al-Sharif in East Jerusalem.

A year before my ban, but more significantly two months after Israel launched its punitive assault on Gaza in July 2014, I, along with two visiting friends, decided to spend time hanging around the walled Old Citya privilege not afforded to Palestinians trapped within and forced outside of Israel’s borders.

Finding a seat on the pavement’s edge, opposite a Palestinian-owned café and a temporary checkpoint—around which stood four or five Israeli officers—we watched the rituals of disciplinary power unfold. Some Palestinian kids were doing bike tricks as the weapon-clad Israeli watchmen looked on intimidatingly. With my friend Nour, whose hijab visually marked her as a Muslim, seated on my left, and Mehdi, whose being Iranian Muslim also marked him with “suspicion,” on my right, our conversation turned to our mutual adoration of Tupac. To add weight to our (my) evangelical enthusiasm, I got out my phone and started playing “Changes,” preaching to an already converted audience about the man Kevin Powell called “hip-hop’s Prophet of rage and revolution.” Musing on Tupac’s ability to connect the ongoing neocolonial warfare in the Middle East with the neoliberal war on drugs in the United States, felt particularly resonant in the context of Jerusalem: a city divided by militarization, in which competing rights to national symbols and Israel’s control over public space have led to the suffering and disenfranchisement of its Palestinian residents.

Photo: Hani Amra

Eavesdropping on our conversation or catching the music that played at low volume, a young, white, American-accented officer blurted out: “Tupac! I love Tupac.” On hearing his shrill enthusiasm, I felt a hot surge of frustration grip me. Sure, I could have taken his glib comment as nothing more than a naive attempt to cash in on rap capital. That is, if his militarized presence weren’t a reflection of a broader logic of entitlement that governs the city. How could an occupier so grossly misunderstand Tupac? How could he not recognize his position within a colonial system that violently polices racialized bodies? Guided by a perverse desire to test the boundaries of unequal power that existed between us, and empowered by our now interrupted conversation, I sarcastically blurted out: “If you really listened to Tupac, then why the hell are you … there, carrying guns and intimidating little children?”

In a city where theft and supremacy are enacted as domestic and cultural policy, acts of reclamation become part of a broader decolonial struggle. In a city where symbolic warfare rages, misappropriating icons of resistance is tantamount to sacrilege.

My accusation, though imperfect, was culturally and politically motivated. Tupac had been central to my political formation. Discovering music that intellectually grappled with the injustices and pain of racism in a way that refreshingly sidestepped academic jargon was empowering. It allowed me to better understand the shared histories of oppression between black and Palestinian communities. And yet, it took a personal confrontation with an Israeli officer for me to fully realize the importance of protecting revolutionary culture from the depoliticizing effects of, in his case, false fandom. Confronted, in that brief moment, by the unholy trinity of state-sanctioned racism, cultural misappropriation, and brazen nonchalance, I would not let Tupac’s legacy be sanitized by a serving member of a state that ushers in a culture of intolerance.

iii. On the Illusionary Dangers of Digital (Dis)Possession

As a vocal agent of black resistance and a revolutionary icon, Tupac exerted influence on black political culture, which in turn crowned him with almost divine status, a responsibility he upheld, but for which he was repeatedly vilified. This tension is captured most poignantly on his album The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory (1996), released under his Makaveli alias just months after his death. The album cover depicts him crucified, his head tilted, his expression withdrawn and suffering. Designed by Death Row’s in-house artist Ronald “Riskie” Brent—but conceptualized by Tupac—the artwork is both prophetic and macabre. The religious metaphor is, among other possible readings, an exploration of the persecution he faced at the hands of anti-black corporate media. The following line from the track “Blasphemy” makes this clear: “the media be crucifying brothers severely.”

Throughout his highly scrutinized career Tupac was acutely aware of the misrepresentation of the mediatized black image, and his desire to take creative and political control was central to his self-presentation. His uncompromising position is made clear in a now famous interview with Tanya Hart on Black Entertainment Television, in which he discusses the limitations of his black role models: Eddie Murphy, Arsenio Hall, and Spike Lee. Speaking specifically about Lee’s seeming lack of solidarity with black artists and his misrepresentation of black women on film, Tupac said: “You can’t compromise our culture and our principles just to put us to work, just to make us appeal to the masses. Because revolutionaries and freedom never came easy.” Reducing the black image to a stereotype for palatable commercial consumption was something he stood firmly against, both artistically and politically—a sentiment the media apparatus diluted and abused, itself a fate that would haunt his legacy.

Photo: Hani Amra

I turn, thus, to the infamous “return” of Tupac at Coachella music festival 15 years after his death, which the artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan has aptly called “a contemporary fable of late capitalism.” His body appeared on stage, a glowing picture of holographic health that starkly contrasted with images from his autopsy. Gone are the bullet wounds, to make way for a clean, easy image, performing on stage alongside Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre. Although the hologram was deployed to blur the line between illusion and reality, it invited more important questions around the politics of representation: what can be seen and heard, by whom, and for whom? Such ideas are brilliantly foregrounded in a John Freeman essay titled “Tupac’s ‘Holographic Resurrection’: Corporate Takeover or Rage against the Machinic?” (2016), in which he offers a political economy reading of the digital manipulation that rebirthed Tupac. Freeman fittingly summarizes the corporate-led sanitization of his black body as a form of “technoslavery”—an enslavement that divorced Tupac’s image from his sociopolitical meaning for the entertainment and consumption of a predominantly white audience. The techno-entertainment logic that birthed Tupac’s holographic resurrection was the cautionary reminder of the violent erasures inflicted on the oppressed through the reimagined imagery of the powerful. It would also offer an inadvertent lesson for the technological de-developments that are working to reimagine Jerusalem away from Palestinians.

iv. On the (Invisible) Violence of Symbolic Resurrection

In 2014, around the time of my confrontation with the officer, a campaign to build the Third Temple launched on the crowdfunding website IndieGoGo. Backed by the Temple Institute, a self-described research organization established in 1984, this mission to rebuild a Jewish temple atop Haram al-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary)—or the Temple Mount, as Jewish communities commonly refer to it—was presented as a solution that would usher peace into the region. Spoken of as the “most contested real estate in the world,” this holy site sparks power dynamics between occupier and occupied. Undeniably the site holds central significance for the three major monotheistic faiths. Contained within the compound’s walls are two major religious Muslim shrines: Dome of the Rock and Al Aqsa Mosque. For many Jewish believers it is to be the site of the Third Temple, though that construction remains a divisive religious and political taboo. For decades it has been a battleground of competing religious-nationalist claims, for which there will never be an “easy” solution. As such, the establishment of a “Temple consciousness” is a direct threat to Palestinian and Muslim communities, to those globally for whom the site is central in religious practice, and as a symbol for Palestinian liberation. For Israel’s religious-nationalists, the site is central to the city’s Judaization project and, in real-estate terms, a visual obstacle to Israel’s nation-brand.

Nasser Soumi, Le Dôme et L’Olivier, 2014, 59 x 59 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Nasser Soumi, Ascension, 2014, 59 x 59 inches [courtesy of the artist]

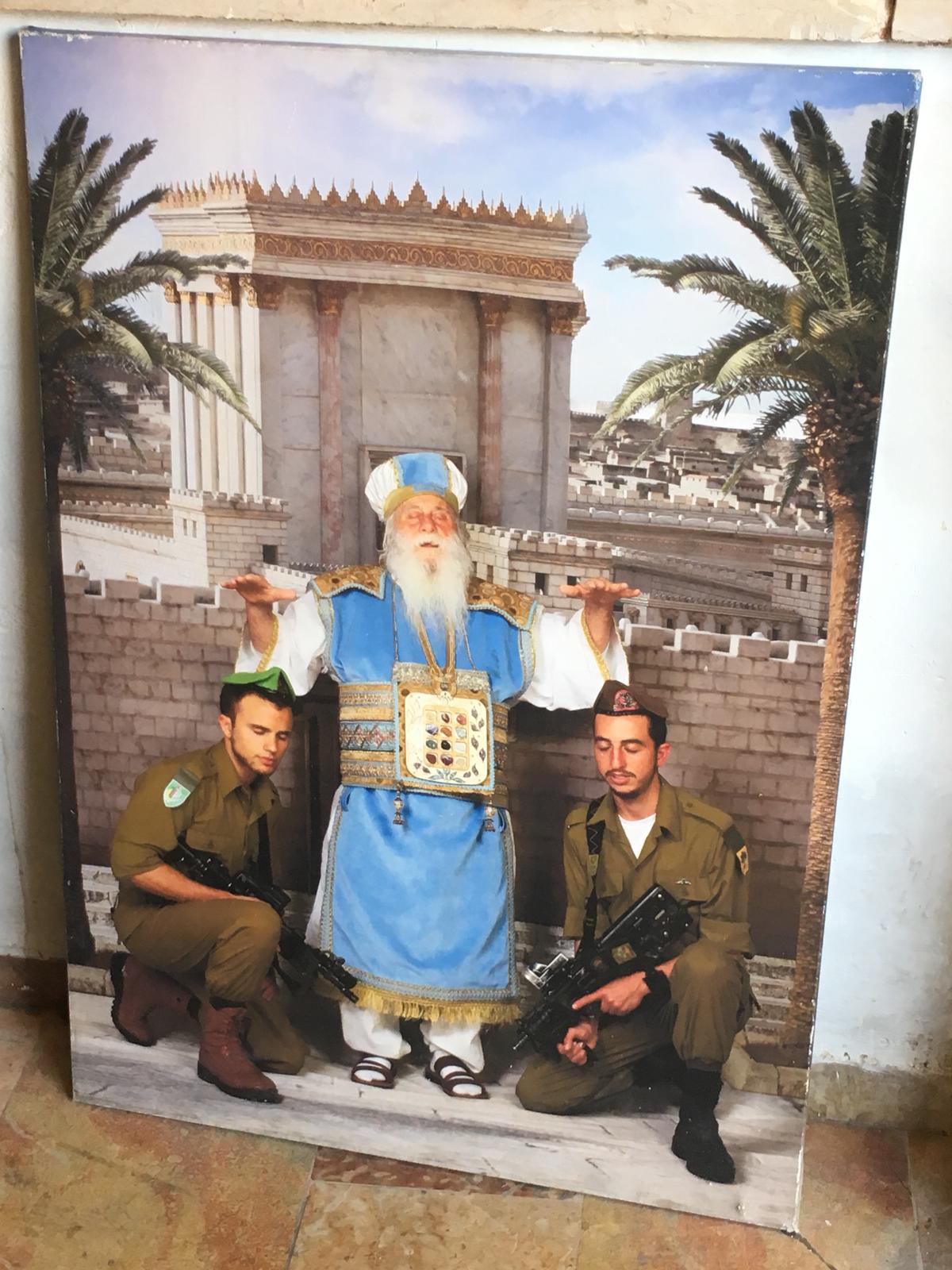

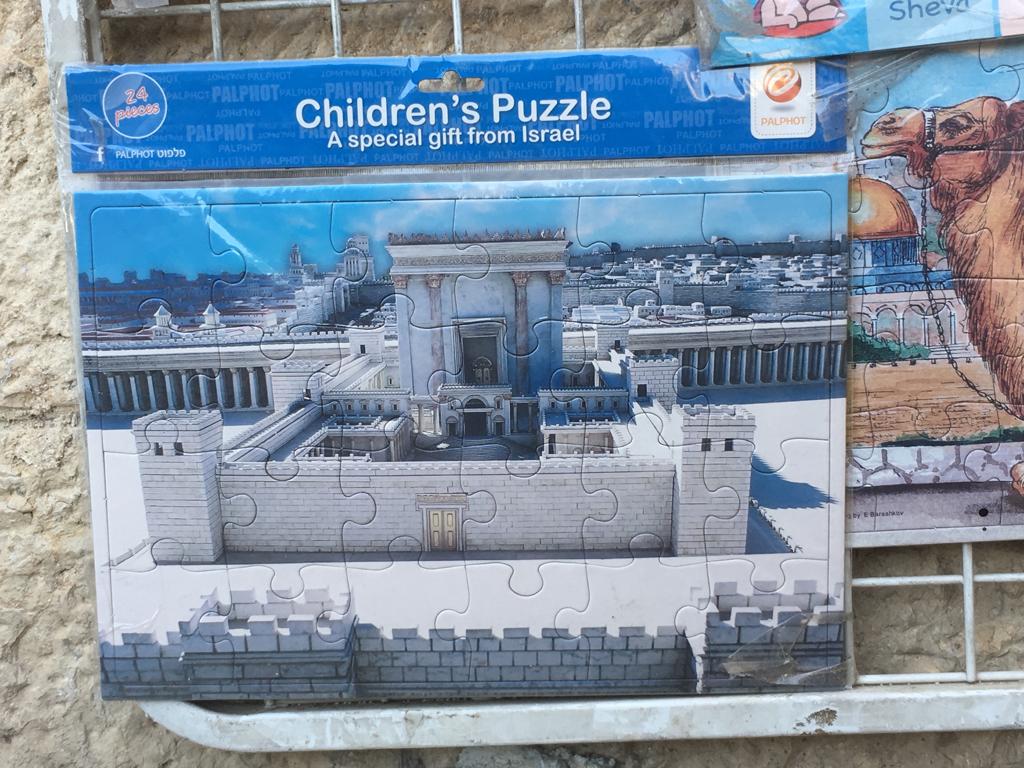

Whether by conspiratorial design or coincidence, a promotional video proposing to build Jerusalem anew, appearing just as Gaza’s population was struggling to reconstruct its destroyed cities, made the timing of the proposition more inflammatory. The campaign videos reveal computer-generated images of the Temple. One presents a utopic vision of a Jerusalem whose skyline has been cleansed of its Palestinian signifiers. Absent is the city’s crowning golden Dome of the Rock and Al Aqsa mosque, and in their place stands the Third Temple. Central to this augmented image is a radically reimagined Jerusalem as a Palestinian- and Muslim- free space. The visual violence is disguised through the familiar aesthetic of sanitized real estate videos. Going beyond its target of raising more than $100,000 to finance the research and development phase, the campaign pointed to the terrifying potential of its endeavor. As a religious enterprise that has grown in economic and political significance over the past three decades, the Temple Institute is one of several Zionist organizations working to normalize (and sell) the idea of rebuilding the Temple. It is not uncommon to find paintings, puzzles, and small-scale replicas of the Temple for sale at shops in the Jewish quarter—formerly the Moroccan Arab Quarter, which, as Abowd discusses in detail, was strategically cleansed of its Palestinian inhabitants in 1967 to give the Jewish State ethno-religious dominance over the city. Whereas the politics that The Temple Institute propagates is not necessarily new, both the dissemination and presentation of the promotional videos reveal a novel strategy. Settler-colonialism is being crowdsourced by a transnational online community.

The idea that technology could offer a “peaceful solution” to global discontents is a familiar one. In the context of Jerusalem, however, it is one of several attempts to disrupt the status quo on the site, ranging from acts of terrorism to divinely absurd digital interventions. I remember reading a bizarre article, published in a 2004 issue of Wired magazine, about Yitzhaq Hayutman, a so-called Israeli cybernetics expert who proposed a “peaceful solution” for the contested Haram al-Sharif site: to beam a hologram of the Third Temple atop the Dome of the Rock, which would “fulfill an ancient, widely revered Jewish prophecy that the temple will descend from the heavens as a manifestation of light.” Hayutman’s holographic solution, allegedly based on his subjective interpretation of the work of an 11th-century Talmudic scholar, would be further realized by creating an immersive virtual temple that would allow for a multiplayer online game. Nutty and far-out as it may read, the creation of a “worldwide virtual reality version of Jerusalem,” as proposed by Hayutman, is not entirely out of line with recent technological developments intended to reimagine the city. A recent article published on Bloomberg.com by Noah Feldman, a Harvard professor of law, raises the alarm on the dangerous advancements in VR technologies being staged at the Western Wall—which borders the site of al-Haram al-Sharif. Rendering a virtual tour of the biblical past in elapsed real time is a “dangerous fantasy,” as Feldman notes, because the “once-radical idea of rebuilding the temple on the site is gradually getting mainstreamed.”

Nasser Soumi, La Raine des Villes 2013, [courtesy of the artist]

Nasser Soumi, Sur la croix, 2015, 39.4 x 39.4 inches [courtesy of the artist]

The birth of the worshiper-as-gamer model, or worshiper-as-crowdfunder model, abides by the restorative power of technology. What appears politically out of line can be erased through the presentation of augmented architectural modeling techniques—an invisible violence that presents an easy solution for what has been lost, or what seeks to be born anew. Beyond the politics of representation, however, it opens up a more serious concern over how neocolonial imagery works in the technological age. The so-called democratizing potential of technological utopias upholds a view of progress as a magic bullet to resolve conflict in the region.

Yet it was only by linking the two seemingly disparate images—the holographic image of Tupac and digitized images of the Third Temple—that I was able to fully consider the insidious ways in which technology can be weaponized against the oppressed. If a politicized rap icon can be made profitable as a holographic likeness for white corporate interests, and a material site of religious and national significance can be erased by digital technologies to make way for the architectural fantasies of ethno-nationalists, how do we preserve the symbols, or indeed icons, of the oppressed? How do we remedy the hollowed-out politics for those who struggle to be seen and heard, and reinstate the sociocultural and political complexity that their narrative demands? Although both images falsely promise a virtuous reality free of conflict—whether through the healed holographic body of Tupac or an ethnically cleansed, digitized vision of Jerusalem—they conceal the (invisible) violence that has led to their (imagined) return. Together they constitute a haunting reminder that technology in the hands of those who wield economic and political influence can translate into (im)material violence for people, or places, bound to power inequalities. Perhaps they explain why ethno-nationalist techno-fantasies risk feeling fanatically real.

Reema Salha Fadda is a writer, editor, and researcher whose work engages with the politics of contemporary artistic knowledge production. She is currently completing a DPhil at the University of Oxford, and focusing on the political economy of Palestinian artistic production. Her writing has been commissioned by leading international publications including Sternberg Press, Frieze, TANK Magazine, ART PAPERS, Ocula, and Ibraaz, where she was commissioning editor of reviews. In addition to developing a lecture series on Arab visual cultures for University of OXford and Darat al Funun, she has programmed cultural events in Palestine, Cairo, and London. She tweets @reemafadda.

Several images accompanying this piece are by Palestinian-born painter and installation artist Nasser Soumi. Indigo, a characteristic color of Soumi’s work, serves to evokes the Mediterranean Sea and the nature of navigation, existence, and human migration. Nasser’s combination of eclectic, manufactured and handmade objects tell the story of where we come from, and where we are going.

Nasser Soumi studied at the National School of Fine Arts in Damascus, Syria and the National School of Fine Arts in Paris, France, with solo and group exhibitions throughout Europe and the Middle East. Currently, Nasser is based in Paris and Beirut. Nasser’s latest exhibition at Mark Hachem Contemporary Art Gallery in Paris runs from February 22 — March 14, 2019.