Jenna Sutela, From Hierarchy to Holarchy, 2015 (left) and Minakata Mandala, 2017 (right), Installation view [photo: Dario Lasagni; courtesy the artist and MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge]

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere

Share:

My introduction to the tentacular exhibition Symbionts: Contemporary Artists in the Biosphere at The MIT List Visual Arts Center (the List) began outside its galleries, at a panel featuring MIT Museum curators. In many ways, this entry point complements the exhibition’s, which aims to “reexamine our human relationships to the planet’s biosphere through the lens of symbiosis, or ‘with living.’” The panel, “Syn /\ Sym: Biology in Art & Design,” convened at the newly opened MIT Museum with William Myers, guest curator of the museum’s shows Gene Cultures; Caroline A. Jones, co-curator of the Symbionts exhibition and professor in History, Theory, and Criticism, Department of Architecture at MIT; and moderated by Jens Hauser, media theorist and curator. The resulting conversation highlighted two strains of thought: innovative progress via design and the revelation of what is already present in interspecies connections—whether mutual, parasitic, or commensal.

Jones referenced the oft-cited phrase from feminist theorist and philosopher of science Donna Haraway, who advocated for “staying with the trouble.” Jones also cited the collective efforts of her all-femme-identifying team including List curators Natalie Bell and Selby Nimrod; their logistical collaboration with the Environmental, Health, and Safety Management Team; and, more broadly, the contributions of women scientific researchers within the field, such as Lynn Margulis; and Jones’ own efforts to push the List to take on the exhibition. Jones noted that Symbionts’ focus upon the interworkings of biological symbioses, rather than on innovative futuristic design, was an example of Haraway’s “trouble.” Just how much trouble, I would learn through the active, radical, and even unruly materials in the exhibition, ones that mirrored the curatorial team’s labor. But before encountering the performativity of dirt, amoebae, fungi, bees, wolves, cress, spiders, mycelium, bacteria, parasites, and spiders, I walked through Gene Cultures.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists in the Biosphere, installation view, 2023 [photo: Dario Lasagni; courtesy of MIT List Visual Arts Center]

Projects by artists—or “bioartists” as described in the brochure—included a mermaid “specimen” by Richard Pell and pink chicken from the eponymous Pink Chicken Project. These works were sequestered behind glass, away from direct interaction with audiences, and laid out on curved tables akin to what fellow nonscientists might envision belonging to a lavish pseudo-science laboratory. One incredible exception was Resurrecting the Sublime (2019), an olfactory collaboration among Sissel Tolaas, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Christina Agapakis, and the biotech company Ginkgo Bioworks, Inc. (with the support of International Flavors & Fragrances Inc.), in which viewers could inhale the scent of now-extinct flowers, synthesized using DNA from samples in Harvard University’s Herbaria.

But for the most part, the works were kept at bay, at a distance intended for what Myers called a “better revolution.” Myers’ characterization of the exhibition aimed to draw a distinction between the dominating effect of genetic code that emerged in 1960s–2000s bio art and the aims of the exhibition—a point that the List’s exhibition press release and a recent interview by Jones were careful to distinguish—but which, unfortunately, was less apparent in the MIT exhibition. In contrast, upon entering the Symbionts exhibition at the List and learning from a gallery attendant that one of the galleries contained live spiders—in Pierre Huyghe’s installation Spider (2014)—I knew this encounter would be more affectively intimate, rather than reliant upon the rhetorical tropes of scientific progress, to the point that the artistic “materials” themselves might press the limits of my presumably individual biological comfort.

Pierre Huyghe, Spider, 2011, Spiders in corner of the wall, dimensions variable [courtesy of the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin]

As Jones notes in her essay “Symbiontics: A Polemic for Our Time,” from the Omnivore-designed exhibition catalogue, printed on eco paper by Gmund and Favini, the acknowledgment of symbiosis—mutual conditions, entanglements, networks—is indeed a polemic rather than a matter of representation or visualization. It is not a given that we acknowledge this foundational fact of biology: We are not alone and, indeed, are in constant exchange. Western neoliberal individualism would, in fact, reject this notion. The state of being-in-relationship takes on new and active political urgency, Jones argues, asking, “If we are dependent on other living entities to survive, how should we acknowledge that affiliation? How shall we live with reciprocity in mind?” These questions lingered as I smelled the pungent dirt used in Claire Pentecost’s installation soil-erg (2012), some compressed into bricks and others stacked like gold ingots, elsewhere lining the walls as currency, all counted according to an alternative banking system. Hidden amid this substrate, tiny laborers of fungus, amoebae, and mites become valued in an abstraction that otherwise disregards their work at renewing the soil.

Paired with Kiyan Williams’ Ruins of Empire II (2022), labor, in relation to the soil, took on the sinister history of slavery in the service of petrocapitalism. An IV bag hangs above a trough and drips a dark petrol-like liquid into a death mask, which is perched on soil that has been cast from mycelia—fungal threads. The work references the slow poisoning of Black communities in Louisiana’s Death Valley, which is overrun by petrochemical plants. In the same gallery, Jes Fan’s Systems II (2018) geometrically scaffolds space, articulating a matrix from flesh-colored piping. Draped over its intersections are blown glass globules filled with melanin, Estradiol, and Depo-Testosterone, materials that allude to a (re)casting of sex and gender.

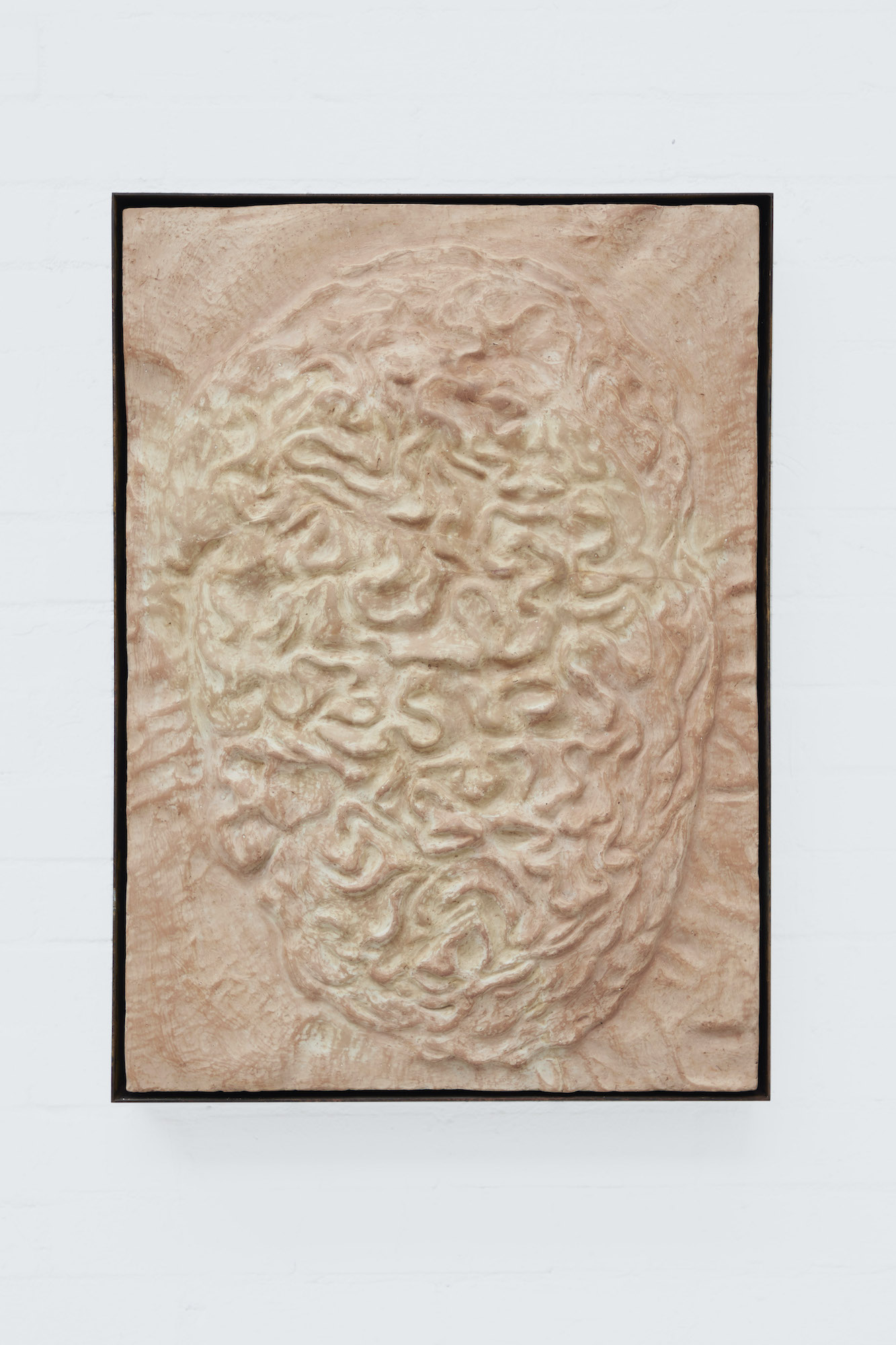

Jenna Sutela, Gut-Flora (Cerebrobacillus), 2022, fired mammalian dung glazed in breastmilk, 35 × 24 inches [photo: Joseph Kadow; courtesy of the artist and commissioned by V-A-C.]

Jes Fan, Systems II, 2018. Composite resin, glass, melanin, Estradiol, Depo-Testosterone, silicone, wood, 52 × 25 × 20 inches [courtesy the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

Predictable material collaborators, such as fungi, recur in the exhibition, such as in Candice Lin’s Memory (Study #2) (2016) and Nour Mobarak’s Reproductive Logistics (2020). Amoebae make appearances, as well, in Jenna Sutela’s From Hierarchy to Holarchy (2015), Minakata Mandala (2017), and in her “Gut Flora” reliefs. Inklings of algae materialize in Anicka Yi’s illuminated tank sculpture Living and Dying in the Bacteriacene (2019). Although common in contemporary art about the biosphere, these “materials” challenged assumptions concerning their agency, and in some cases converted their materialities—in artistic terms—from inanimate matter to animate collaborators. Lin’s sculpture feeds on communal urine, generously supplied by museum staff. Mobarak’s self-portrait decomposes hair and sperm preserved from past lovers. Sutela’s amoebae nourish themselves through labyrinthine quests for oats in low light, and Yi’s wooly algae absorb light. They become performative participants, or “actants,” as philosopher Bruno Latour might argue, with and even beyond the artist and the viewers. They all turn into collaborators.

Špela Petrič’s Confronting Vegetal Otherness: Skotopoiesis (2015) and Alan Michelson’s Wolf Nation (2018) reveal the slow growth of cress plants and red wolves at rest, respectively. In Petrič’s installation, the camera records seemingly imperceptible sprouting around the silhouette of the artist’s shadow. Michelson’s webcam installation captures wolves in a purple glow, seemingly at ease, yet also surveilled—a potent connection with the Lenape Munsee, also known as the Wolf Clan. The wolves and cress do not demand viewer attention but instead perform at the edges of our awareness, challenging us to recognize our deep intertwinements.

Crystal Z Campbell, Portrait of a Woman I and Portrait of a Woman II, 2013, Upcycled wood, MDF, custom 3-D laser-cut solid glass cubes of HeLa cells (image of HeLa cells made with Dr. C. Backendorf and G. Lamers) and of Henrietta Lacks, 35 × 6 × 6 inches each [photo: Colin Conces; courtesy the artist and Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha]

Crystal Z Campbell, Portrait of a Woman I and Portrait of a Woman II, 2013, Upcycled wood, MDF, custom 3-D laser-cut solid glass cubes of HeLa cells (image of HeLa cells made with Dr. C. Backendorfand G. Lamers) and of Henrietta Lacks, 35 × 6 × 6 inches each [photo: Colin Conces; courtesy the artist and Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha]

Unexpected collaborators emerged in the work of Miriam Simun’s The Sound of a Bumblebee Refusing to Colonize an Artificial Nest (2022), that includes beeswax, lemongrass, bee pollen, dried flowers, and local Massachusetts fruits; together these elements index the conspicuously absent bees. Simun’s film Interspecies Robot Sex (2022) follows two intersecting pollinating “rituals” for the pear trees in Dangshan County of Anhui Province, China. In one narrative thread, workers seated around a communal table pollinate the flowers by hand. In another thread, Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering introduces the “RoboBee,” a flying robot used for crop pollination. Bees, once again, are absent. Viewers, however, sense the insects’ presence quite literally in the three-channel audio that buzzes beneath the viewing bench, in seeming defiance of the bees’ obsolescence. Sharing poignant resonances of erasure are Crystal Z Campbell’s works Portrait of a Woman I–II (2013) and Friends of Friends (Six Degrees of Separation) (2013–2014). In Portrait of a Woman I–II (created while the artists was in residence at Amsterdam’s Rijksakademie, as noted in one of the essay-like labels), two portraits engraved with HeLa cells, and another with the visage of Henrietta Lacks herself, are partially covered, as if offering shelter that was previously denied. The cells are known today as “immortal,” and have contributed to significant progress in scientific research for leukemia, AIDS, and the development of the COVID-19 vaccine, among many others. But the work asks, at what cost, as the cells were extracted without Lacks’ permission. A simple line of 1940s slides conjures the harvest, capture, and immobilization of the cells in harrowing abstraction. The cells, now long deceased, actively memorialize Lacks’ legacy, and simultaneously lay bare a system that persists in racial-capitalist medicalization.

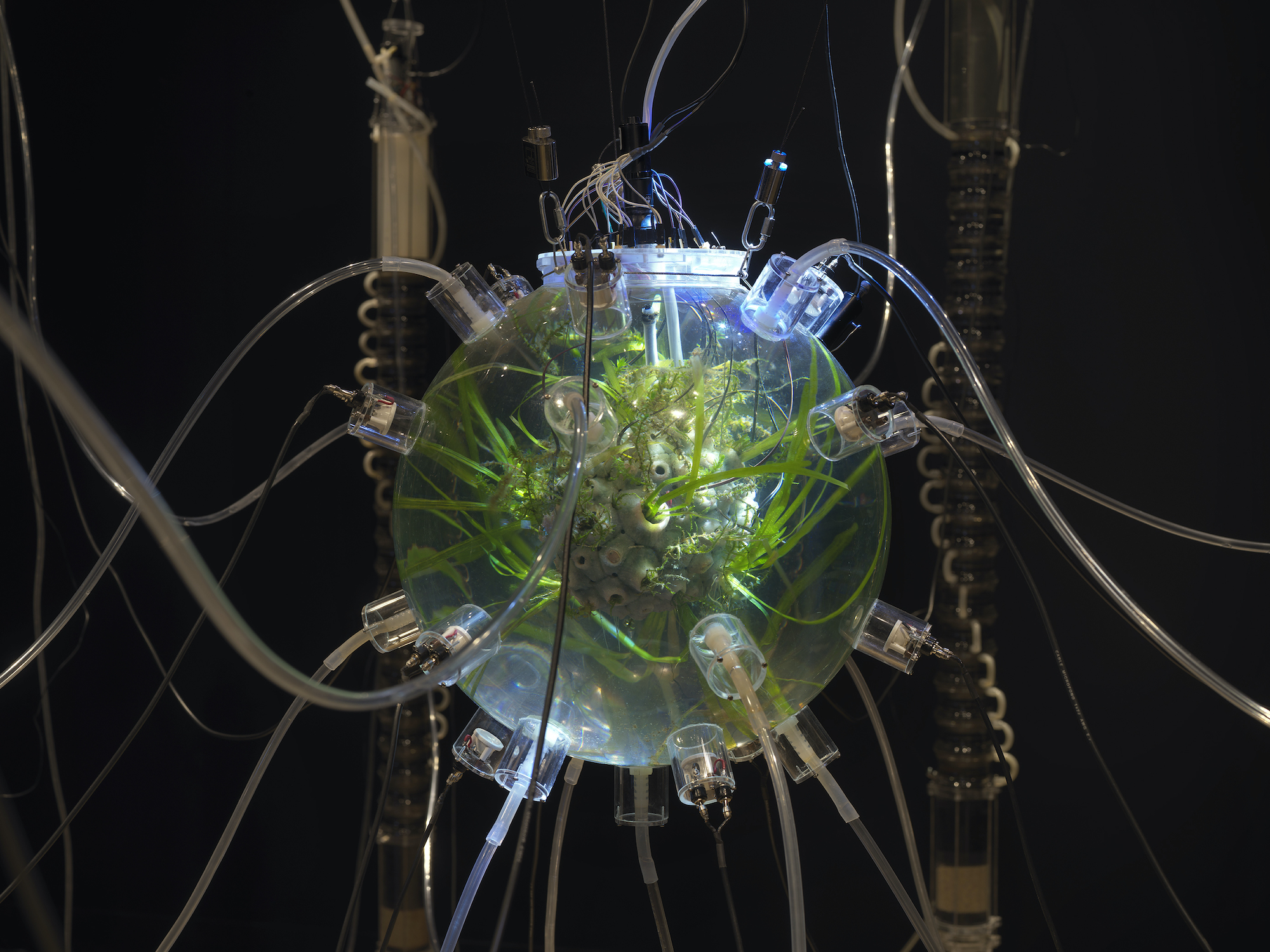

Gilberto Esparza, Plantas autofotosinthéticas [Autophotosynthetic Plants], 2013–14, Polycarbonate, silicon, stainless steel, graphite, electronic circuits, local waste water, natural pond water with microalgae and microorganisms, plants, shrimp, fish, sound 157×157 inches [photo: Dario Lasagni; courtesy the artist and MIT List Visual Arts Center]

Each collaborative entity mobilizes its own kind of micro-performance, but together they maintain a coherence through the way we simultaneously apprehend them in the sensorium. As such, the materials feel less instrumentalized by aesthetics and more mysterious. But upon encountering Gilberto Esparza’s mammoth sculpture Plantas autogotosinthéticas [Autophotosynthetic Plants] (2013–2014) I sensed the same instrumentalization and distance that I found troubling in Gene Cultures in the work’s network of hydraulics, created with assistance from scientists and urban activists, stretched across the space. Long vertically suspended tubes collated sewage from greater Boston and MIT’s campus into towers that fed into a filtration system operated by bacteria. The feeding bacteria produced an electronic current to power a light for a central aquarium hosting crustaceans and microalgae. Here, waste becomes electricity. The system is monitored by a station adjacent to the sculpture, and documentation from the research process appears on screens. The self-contained ecosystem certainly revealed the interrelationships of sewage, living organisms, and electricity, but trafficked in the aesthetics of spectacle that seemed oppositional to the rest of the exhibition. The centralized design, height of the work, and control station contributed to the disconnect. Even as it drew human viewers toward awareness of the sustenance of creatures, it also reified a certain contemporary scientific sublime that seemed more focused on its own mechanisms rather than revealing such systems’ entanglements in the world, beyond its self-sustainability and promise of renewable energy.

Pamela Rosenkranz, She Has No Mouth, 2017, Sand, fragrance, LED light, light controls, dimensions variable. [photo: Timo Ohler; courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers. © Pamela Rosenkranz]

In the final gallery, isolated from other works and offering a return to the mystery I craved, Pamela Rosenkranz and Pierre Huyghe’s installations merged in a salient rumination. Rosenkranz’s calming circle of pink sand with an accompanying glow affectively clashed with my fear of harmless cellar spiders in Huyghe’s many-legged installation. Rosenkranz’s work is infused with the scent of Calvin Klein Obsession for Men and alludes to the sensorial aspects of attraction. The aroma is deployed to infuse a story about T. gondii, which causes toxoplasmosis—a parasitic disease found in cats that can spread inadvertently to other host species—and emits an alluring pheromone. Rosenkranz’s elegant litter box radiates a noncommercialized perspective of the pheromone in this absurd scent-scape that, perhaps, tempered my desire to run from Huyghe’s spiders. Hanging upside-down in the corners of the gallery, his collaborators were barely perceptible. At the same time, they drew me toward those corners—oft-forgotten interstitial spaces between expanses of manicured walls—to behold the creatures probably also occupying corners of my own home. In the artificial habitat of the white cube, they nevertheless spun dwellings, or else departed (the staff released 20). The spiders’ free rein was hair-raising and offered what the exhibition promised: trouble, polemic. It was as if the white walls disappeared altogether to unveil the symbiotic biological worldview that was always already before and around us.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists in the Biosphere, installation view, 2023 [photo: Dario Lasagni; courtesy of MIT List Visual Arts Center]

Author’s Note: I am grateful for the roundtable discussion included in the exhibition catalogue, “Symbiosis, Reciprocity, and Indigenous Epistemologies,” Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, with contributions from Christina Agapakis, Leah Aronowsky, Natalie Bell, Rogier Braakman, Bruce Clarke, Ryan E. Emanuel, Scott F. Gilbert, Caroline A. Jones, Selby Nimrod, Claire Pentecost, Tiare Ribeaux, Jolene Rickard, S. Margaret Spivey-Faulkner, that elaborates crucially upon the purview of “with-living” within Indigenous epistemologies light of historical colonialism. As Claire Pentecost eloquently opens the conversation, “The question at hand is: How does a theory become a worldview? For Indigenous people, it is the worldview of seeing symbiosis everywhere.”

Laurel V. McLaughlin is a writer, curator, and art historian based in New Haven, Connecticut, CT. Her work examines research-based sculpture, installation, new media, and social practice, and performance activated by performance concerning globalized migration and ecological networks. McLaughlin is completing her PhD at Bryn Mawr College, and her work has been published in Art Papers, BOMB Magazine, The Brooklyn Rail, Performa Magazine, ContactQuarterly, and Performance Research, among others.