Suzanne Lacy: We Are Here

Suzanne Lacy, Annice Jacoby, Chris Johnson, The Roof Is on Fire, 1993-94, performance, City Center West Garage [photo: Gary Nakamoto; courtesy of the artist and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco]

Share:

If you have never seen the name Suzanne Lacy on a wall label in a museum, or even a gallery, it is not that you haven’t been paying close enough attention. Unlike almost every other contemporary artist working today, you are more likely to have seen her name or work on your local news channel. Lacy has spent her artistic career, which began in the early 1970s, expanding the concept of performance art to include strategic conversations—a choreography of dialogue, as she has put it—with members of communities experiencing various forms of distress or resisting oppressive external forces. Although driven by timely issues, Lacy’s work is nonetheless formally bold and conceptually complex. Her artistic interventionism, which is now mostly referred to in contemporary art as “social practice,” is not the sort that fits comfortably within the white cubes that still, despite the proclaimed open-mindedness of its underlying structures, upholds the rigidity of the (male-dominated) canon. Needless to say, an artist such as Lacy, who travels the world and works closely with underrepresented people—rape victims, inner-city youth, sex workers, immigrants, low-wage laborers, and the elderly—does not align with the still primarily white, male, Western (or at least Western-educated) artists whose names, paintings, and sculptures are the celebrated standard of such an institutionally sanctioned lineage.

Here We Are [April 20–August 4, 2019] is a bit risky, spanning both the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts—the city’s main art museums—which are neighbors amid downtown’s atmosphere of tech startups–turned–Fortune 500 companies and ready-to-retail accompaniments, (think robot-made smoothies, touchscreen cafés, service-free Amazon grocery stores, etc.). Within this context, the work on view is clearly all the more germane. In direct response to the drastic transformation of the city from liberal enclave to economist chic, the entryway to the exhibition greeted viewers with Beer Bucket/Champagne Bucket, an installation from Lacy’s Central Valley series (2008–ongoing). As the elevator doors opened, immediately we saw stacks of folded T-shirts leaning against a wall and just below a selection of large-scale c-prints of scenes from yard sales in the San Joaquin Valley. The shirt atop each pile bore quotes from Lacy’s research into stock reports that follow trends of the aforementioned “buckets,” referred to as such to connote such containers as they pertain to low-income households—the beer stocks—and high-income households—the champagne stocks, of course. One read, in part, “Wal-Mart has benefited as Americans, squeezed by higher gasoline and food costs, tighter credit and a slumping housing market, try to shop at cheaper stores. The company, which had been bruised by unrelenting attacks by union-backed groups, has seen criticism diminish.”

Suzanne Lacy, We Are Here, installation view, 2019 [photo: Charlie Villyard; courtesy of the artist and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco]

From this introductory installation the exhibition continued through a corridor where viewers found themselves flanked by black boxes featuring Lacy’s more recent video work, The Circle and the Square (2017). To the right we saw multiple 3-D light boxes within which each projected a video telling the individual stories of residents of the area near Brierfield Mill, once one of England’s largest textiles mills that has been closed for years. On our left, another example of the dire and sometimes heartwarming consequences of globalized capitalism unfolded with a large-format video showing interfaith members of a nearby community center engaged in sessions of Sufi chants. Working with these retired mill employees, religious initiatives, and a local arts nonprofit, Lacy gathered information through interviews, workshops, and ceremonies to both reunite the town and make the videos. Beyond this two-sided installation, the space opened up into a large gallery that presented some of Lacy’s earlier and most signature works that address such issues as labor hierarchies and wage inequalities, as well as the deep-rooted pain and collective anguish wrought by sex crimes and violence against women.

Lacy uses bodies, personas, and youth as vehicles through which to explore various aspects of community and culture, such as violence against women, as well as labor and class. It becomes clear that the imagery in her works often incorporates a physical cover or covering of some sort. The T-shirts of Beer Bucket/Champagne Bucket represent a simple way to cover oneself—for protection or to propel a message. In the religious scenes of The Circle and the Square, men and women cover their heads with traditional hats and scarves, and overall the work deals with the ever-controversial textile industry. In a restaging of Alterations (1994), a woman continuously sews garments from heaps of either red, white, or blue used clothes. Her own body and labor are somewhat obscured by the large mounds of fabric, which reach at least 10 feet in height. Nearby several examples of the recurrence of quilts in Lacy’s work were also on view, the most prominent of which was The Crystal Quilt (1985–1987), yet another thing with which to be covered and comforted.

As with many artists working through performance, masks—another cover—also appear throughout Lacy’s practice. Masks are sometimes used as a form of therapy in art, as well as in theater, and in Lacy’s work they are shown from a diaristic and exclamatory perspective. El Esqueleto Tatuado (The Tattooed Skeleton) (2010), for example, deals with public representations and receptions of domestic violence in Spain. She also uses masks in more outwardly performative ways in Inevitable Associations (1976), one of several performances in which Lacy transformed herself into an elderly woman; and The Bag Lady (1977), wherein she addresses not only aging but also homelessness and its juxtaposition with corporate money that fuels the arts by camouflaging herself as an elderly homeless woman and positioning herself outside high-end commercial galleries as collectors, consultants, and critics strolled in and out.

Suzanne Lacy, We Are Here, installation view, 2019 [photo: Charlie Villyard; courtesy of the artist and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco]

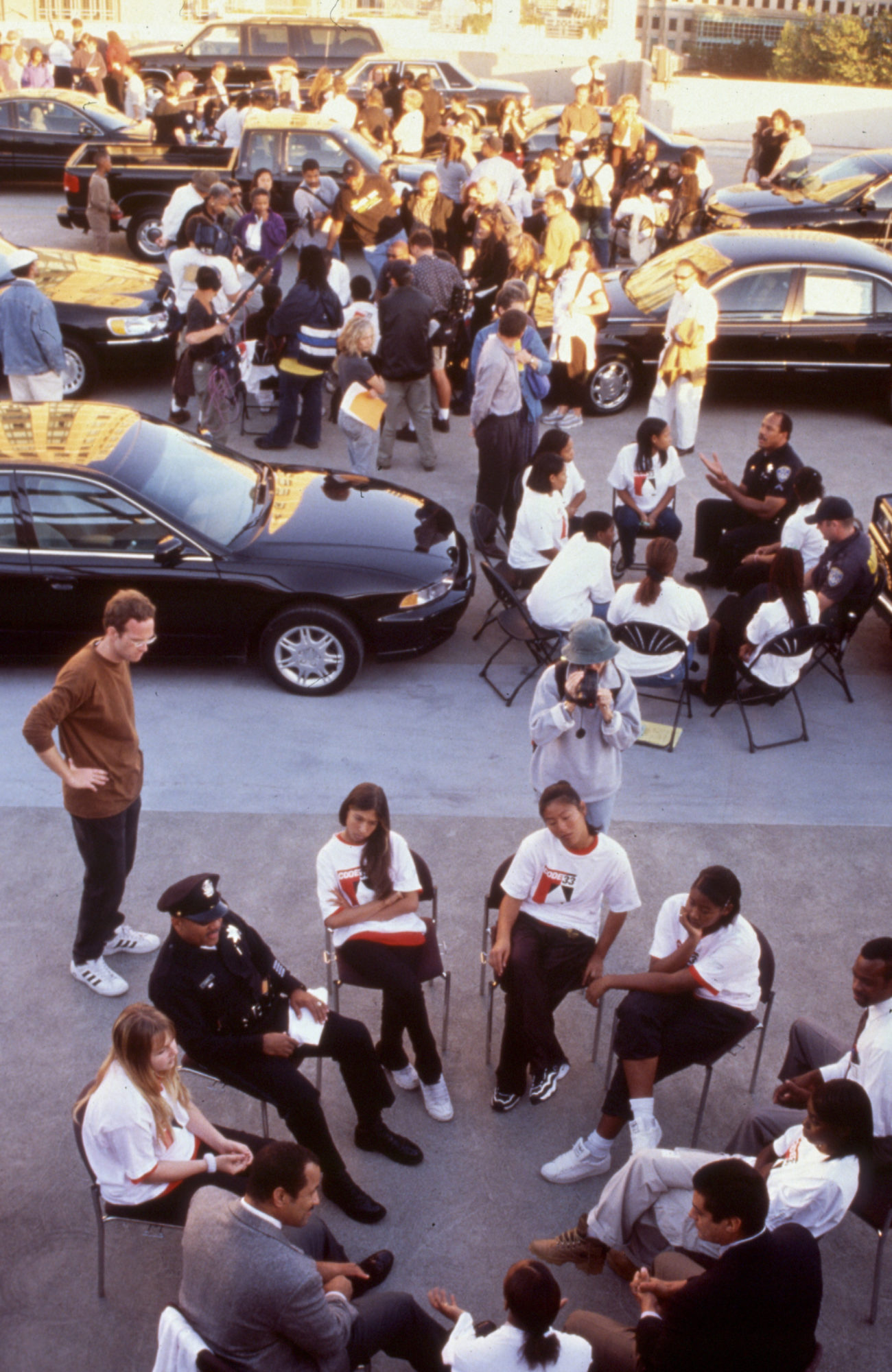

Other forms of cover or coverage include cars and rooftops in which Oakland youth discussed excessive force and racial profiling with policemen, as was the case in Teenage Living Room (1991–1992), which took place during her long-format, wide-ranging series The Oakland Projects (1991–2001). In addition, Lacy has also used cloaks, hoods, blindfolds, and animal carcasses or organs in her work, all of which were incorporated into pieces related to violence against women and the vulnerable battleground that, too often, is the female body. The use of imagery and objects that cover, in one way or another, may be due to the revealing nature of Lacy’s work and the pain or obstacles that it lays bare. Perhaps the acknowledgment of such wounds, whether physical or emotional, prompts the procurement of a shield, healing bandage, or cast-like covering to take form as she works through such contentious issues and finds ways to tell her collaborators’ stories.

Not surprisingly, the disclosure of cultural and political issues that still haunt the US coincide with the origins of Lacy’s work, which began during the inception of Judy Chicago’s Feminist Art Program in 1970. Her first seminal and deeply feminist piece, Three Weeks in May (1977), consisted of more than 30 events, such as media interventions, performances, and activist conferences. An early and palpable example of Lacy’s unique ability to take art out of itself, Three Weeks in May, brought communal outrage about daily reports of rape and sexual violence in Los Angeles directly to the mall of City Hall and the very streets where such heinous crimes had taken place. Yet within the retrospective We Are Here exhibition, the artwork was inherently separated from the action for which it stood. At the time, Lacy and her many collaborators—chief among them fellow performance artist Leslie Labowitz-Starus—widened the scope of the original work of Three Weeks in May by addressing the wounds that such egregious acts inflicted upon Los Angeles communities. In so doing, they staged public events such as holding widely covered press conferences at the Office of the City Attorney; organizing simultaneous “moments of concern” at churches around the city; and hosting slide presentations at the Edison Building that showed evidence of assaults on women. These actions carried the conversation about violence against women from inside the insular gallery into a larger, public consciousness, as well as bringing it to the attention of city councils. This was not an art project, it was an artistic call to action—and although awareness and national discussion of such violence has broadened in the years since, Lacy is able to bring back to the fore the sad fact that even today policy still dictates that men charged with domestic violence can purchase and carry firearms, including semi-automatic weapons, here in the world’s “bastion of freedom.”

Suzanne Lacy, Julio César Morales, Unique Holland, Code 33: Emergency, Clear the Air!, 1997-99, performance, City Center West Parking Garage [photo: Kelli Yon; courtesy of the artist and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco]

In Three Weeks in May, this reminder comes in the form of Lacy’s stamped maps-cum-paintings, which notate all reported incidents of rape at the time in Los Angeles. The sprawling, wall-mounted maps, presented as a centerpiece of the project, are trampled with the blood-colored, alarming-red word RAPE overlapping itself to the point of illegibility in certain, concentrated areas. Back in 1977 these works served as irrefutable proof, outside of the art world, that the lives of women were not prioritized on any local, state, or federal level. But as a woman looking at them as paintings in a museum in the spring of 2019, it is hard not to scoff as 18 states around the country send up anti-abortion-legislative test balloons, hoping to float one straight to the steps of the Supreme Court and strike at the feminist core of Roe v. Wade.

Suzanne Lacy, Pilar Riaño-Alcalá, La piel de la memoria revivida / Skin of Memory Revisited, 2017, mixed media instillation, video projections, sound [photo: Tony Mastres; courtesy of the artist and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco]

Even though Lacy’s kind of art rarely fits into institutional norms, and is thus rendered less potent when viewed after the fact in the sterility of a museum, it is nonetheless more and more critical for artists of her esteemed ilk to be remembered, understood, and taken into serious consideration. Far too much contemporary art, especially in the face of one of our most politically regressive moments in decades, addresses literally nothing, and speaks to no one other than those who want to beautify their living rooms. Too many artists shy away from tackling difficult issues that highlight the personal within the political because they fear it will be read as overtly activist, and therefore somehow less than sophisticated or conceptual. Still others may see the conservative grip that aims to strangle rights for women, LGBTQ, the elderly, the pre-existing-conditioned—the generally underprivileged—as problems too big and interwoven to adequately address through art. Lacy, however, remains engaged. She continues to find new ways of bringing people together through photography, film and video, sculpture, installation, drawings, books, and most importantly through the performativity of dialogue brought into the public sphere. There is much to be learned from her example. She reminds us that nothing breathes such life into repressive political agendas as looking the other way, idly choosing surface over substance.

Courtney Malick is a contemporary art curator, writer, and editor based in Los Angeles/San Francisco. Her work focuses on video, new media, sculpture, performance, and installation, and parses sociological issues and cultural shifts. Since receiving her MA from the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College in 2011, she has organized exhibitions and discursive events in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Miami. Malick also contributes to a range of art publications, including Art in America, ARTnews, CURA., and Flash Art, as well as being a founding member and ongoing collaborator of DIS Magazine.