Spiritual Migrations

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS November/December 2000, Vol. 24, issue 6

After a number of years spent earnestly trying to discover diverse cultural identities, sometime around 1990 the art world and the world at large began to suspect that identity had already been hybridized every time anyone looked at it, and that we might as well get used to. Looking at African-American culture, some began to say that the kind of sampling of other musics practiced in hip-hop and rap were only the latest example of borrowing mainstream symbols in order to transform or subvert them. The paintings of Jean-Michel Basquiat, viewed freshly after the posthumous 1992 retrospective at the Whitney, began to look less than graffiti art and more like an inventive hybrid iconology.

Attuning themselves to the implications of these conversations, plus such things as the example of David Hammons, young African-American artists began to construct their own hybridized heritages. Some, such as Kara Walker and Michael Ray Charles, adapted and sought thereby to subvert 19th-century racist stereotypes, and they stirred considerable antagonism in the process. Others, most notably Leonardo Drew, created constructions of cotton and burnt wood that seemed like elegant metaphors for African-American experience even as they referenced the postwar avant-garde of arte povera. By the time the decade ended, a growing number of such artists had attracted national attention. One of these was the Atlanta-based artist Radcliffe Bailey.

Leonardo Drew, Number 215, 2019, Wood, paint, and sand. Dimensions Variable. Installation view: Leonardo Drew, Galerie Lelong & Co., New York, 2019 © Leonardo Drew. Courtesy of Galerie Lelong & Co.

Leonardo Drew, Number 305, 2021 Mixed media, Dimensions variable. Installation view: Leonardo Drew, Galerie Lelong & Co., New York, 2021. © Leonardo Drew Courtesy of Galerie Lelong & Co.

At age 32, Bailey has achieved something close to the level of respect attained by Walker, who was his undergraduate art-school classmate, but without the downside of controversy. In fact, Bailey is Increasingly named, and collected, alongside Drew, who in some ways he resembles in his metaphoric evocation of the intricate history of Americans of African descent. Bailey’s work is in over a dozen museum collections, and a large-scale painting by him greets international arrivals on Concourse E of Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport, where it was installed as part of the expansion of the airport art program for the 1996 Olympics.

At about this time, Bailey moved towards his now-characteristic use of greatly enlarged prints from family tintypes (not always of relatives whom anyone remembered), surrounded by a variety of contrasting frequently intense colors that, at this time, referred to African-American quilting practices among other things. Phonetically transcribed words from spirituals such as “In Nuh Watuh” (the possibility of racist parody neutralized by the dignity of the surrounding painting) appeared in these paintings alongside lucky sevens and other emblems of the African-American South; soon, they would be joined by the axe of the Yoruba divinity Shango, numbers and names referring to the slave trade and the Middle Passage across the Atlantic, and bottles and small velvet bags containing objects like the ones consecrated in Diaspora religious practices. Bailey was on his way towards a style of cultural hybridity that didn’t so much communicate a single message as provide a space for imaginative understanding: he was creating his own deliberately disconnected mythic spaces, held together by their compositional strength and an intuitive sense of rightness that overcame any objections based on historical associations. The African Diaspora symbols and objects that Bailey assembled in his paintings came from all over the Americas, but they all sprang from similar wellsprings of emotion and preserved traditions.

Bailey was an exhibiting artist even before his graduation in 1991 from the Atlanta College of Art, though his immense reproductions of fragments of cabin walls with equally fragmentary African-American domestic scenes painted on them first appeared in a gallery exhibition that summer at Atlanta’s McIntosh Gallery.

Radcliffe Bailey, Caravan, 2018, mixed media, 120 x 72 x 12 inches © Radcliffe Bailey. [Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York]

Only a year or so later, Bailey had his first museum show at the Mint Museum in Charlotte, and by 1994 he had produced a full-scale installation work for the “Equal Rights and Justice” exhibition at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art. In the meantime, Bailey himself had appeared in the 1992 video of Arrested Development’s “Tennessee,” marking a close association with musicians that would later result in an entire series of paintings devoted to musical imagery.

“Places of Rebirth,” a 1992 exhibition at Atlanta’s TULA Foundation Gallery, established Bailey’s lasting themes carly. Though his characteristic palette was the mixture of flat and gloss black then popular with area artists, this exhibition combined these dark paintings (one of which was dominated by the dates of birth and death of a family member) with a floor installation in which a birdhouse was surrounded by candles, cowrie shells in sand, peanuts, and flower petals offerings that already loosely referred to West African cultural survivals in the Americas.

Though he began with evocations of family heritage, Bailey moved outward to historic social topics; Alter for Four, the installation, for the High Museum, was a shrine to the children killed in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing, with their photographs mounted high on an altar-like wooden wall roped off by fire hoses. Adjacent pews encouraged contemplation to the accompaniment of John Coltrane’s “Alabama” (which Coltrane composed soon after the bombing as a memorial piece), played gently on a tape player concealed in a vintage radio.

Radcliffe Bailey, Blue Black, 2016, glass, ink 61 x 53 x 13 inches © Radcliffe Bailey. [Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York]

Radcliffe Bailey, Other Worlds Worlds, 2011, mixed media, 75 x 120 x 115 inches © Radcliffe Bailey. [Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York]

Spiritual Migration, Bailey’s recent (summer 2000) installation commissioned by the Atlanta College of Art Gallery for the National Black Arts Festival, began, literally and metaphorically, with a photograph of Bailey’s grandfather’s tobacco fields, and with the fact that his father is a railroad engineer. From these two points of departure, there flowed a lyrically concise symbolic commemoration of family heritage and the communal impulses surrounding it.

Radcliffe Bailey, Caravan, 2018, mixed media, 120 x 72 x 12 inches © Radcliffe Bailey. [Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York]

Inspired at least in part by Basquiat, Bailey’s signature style also derived from regional examples that blended Robert Rauschenberg’s overlaid photographic references with the plexiglas-covered object-filled niches that Anselm Kiefer was incorporating into his work circa 1990. Bailey’s distinctive contribution was the recognition that the cultural mix-and-match practiced by African societies in the Americas, about which the theorists Robert Farris Thompson and Paul Gilroy were writing at the time, was an exact conceptual parallel to the sometimes bewildering blending of cross-cultural references undertaken by artists such as Rauschenberg and Kiefer. To borrow their styles to express the truths of the African Diaspora, then, would be both in the spirit of the Diaspora and firmly in conversation with the primary visual vocabularies of contemporary art. The transfer of meaning through the assemblage of objects and images has remained Bailey’s strategy to this day.

The photograph, rendered in sepia and framed monumentally, greeted visitors to Spiritual Migration. On the other side of the gallery wall, similar vintage photographs of riverbanks surrounded a line of glistening glass jugs half-filled with water, representing the Mississippi. A maze of railroad tracks emblazoned on the far wall led out of the side “river” gallery into the main gallery, in which shelves of drying tobacco leaves, sugar cane, and cotton balls emblematized the export commodities grown by African Americans and shipped out by rail. Dominating one wall of this gallery was a monumental sepia-toned photo of African Americans on a station platform seeing off a trainload of other African Americans, symbolic of the great migration by which so many left farm labor forever for industrial jobs. Another wall bore railroad-oriented ancestral shrines juxtaposed with dates and places of slave rebellions, collapsing together a complex of meanings that range from the railroad as path of liberation in the first half of the 20th century to the Underground Railroad’s path out of slavery in the first half of the 19th century. Throughout the gallery, recorded waves and bird cries mingled with railroad noises.

Rather than being interpreted in any strict logical sequence, the many associative elements in Spiritual Migration blended to form a space for contemplation, in much the same way that Bailey’s paintings do.

And indeed, Bailey has incorporated the crossed-track imagery and copies of photographs from the installation into new paintings that were exhibited earlier this fall at Atlanta’s Fay Gold Gallery, Bailey’s primary dealer for most of the 1990s, Continuing his practice of developing an integral symbolism that can be expressed in many different genres, Bailey has stated his intention to present further elaborations of the migration theme in his solo exhibition at the gallery, opening in early November.

Along with this new work, Bailey recently produced another site-specific installation for the Birmingham Museum of Art (on exhibit there through December 31) on the theme of “The Magic City” rhyming the historic nickname for Birmingham with the visionary use of the term by Birmingham native Sun Ra, whose improvisational music on the 1965 record of that title celebrated an imagined place of balance and harmony where evil would be overcome and beauty be triumphant. Bailey’s new works also honor that style of balance, commemorating life transitions in characteristically oblique fashion and auguring a new blend of historical consciousness and personal recollection.

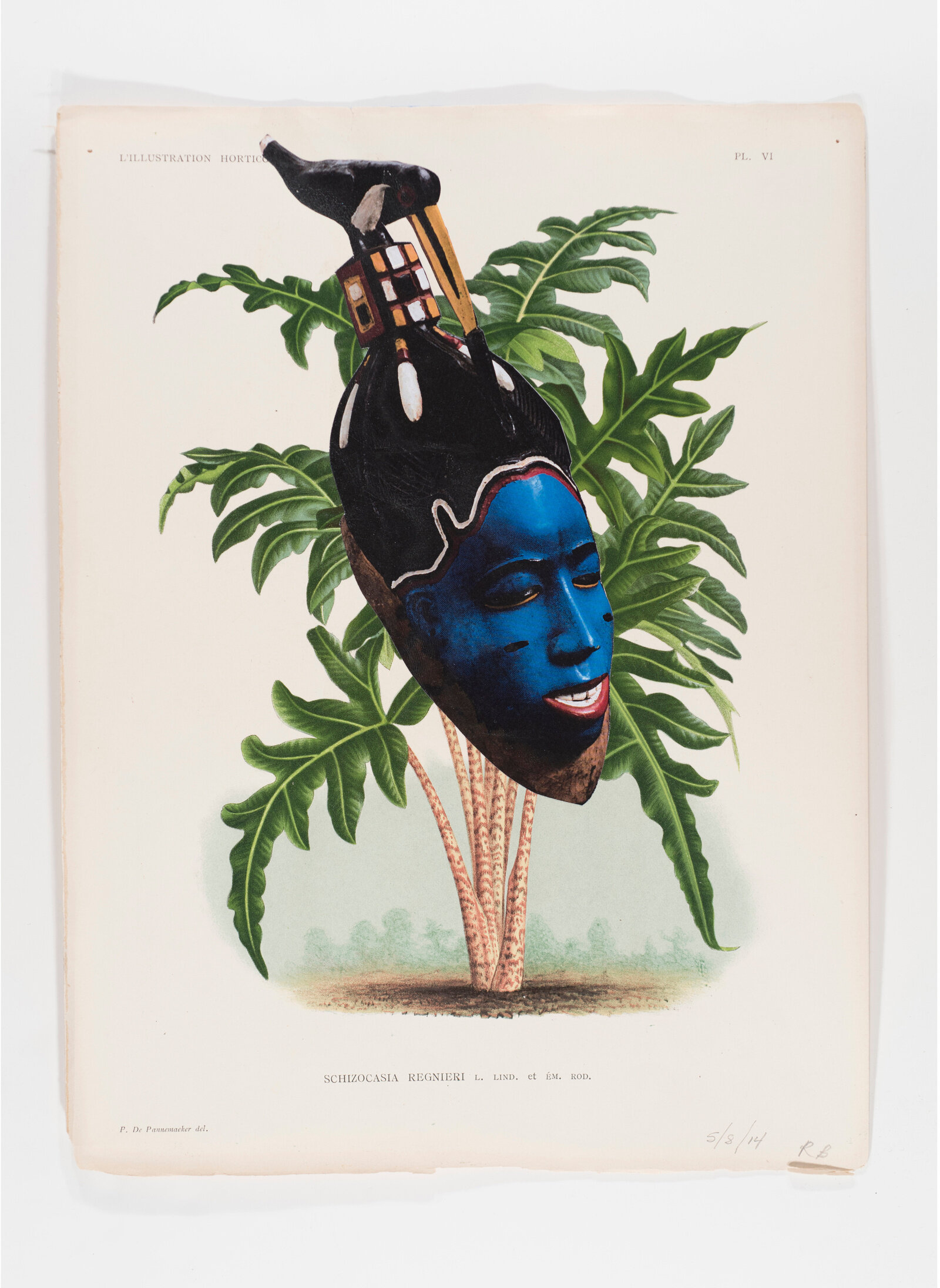

In speaking about Spiritual Migration, Bailey described his overall practice as being “like a self-portrait where I’m visually writing a story in space. There’s both fiction and non-fiction, but the stories I am telling could be true.” But Bailey’s quest to include what he terms “another level of history that allows viewers to find themselves in the work” has resulted in such things as, in the case of the paintings made for the “Magic City” exhibition, the incorporation of photographs of African sculpture from the Birmingham Museum of Art’s permanent collection, documented by Bailey himself in a series of visits. Bailey’s brand of hybridity is intensely personal, but it isn’t self-indulgent. His art deals deeply with African-American themes, but its emotional impact cuts across a fair number of cultural divisions.

And indeed, Bailey has incorporated the crossed-track imagery and copies of photographs from the installation into new paintings that were exhibited earlier this fall at Atlanta’s Fay Gold Gallery, Bailey’s primary dealer for most of the 1990s, Continuing his practice of developing an integral symbolism that can be expressed in many different genres, Bailey has stated his intention to present further elaborations of the migration theme in his solo exhibition at the gallery, opening in early November.

Along with this new work, Bailey recently produced another site-specific installation for the Birmingham Museum of Art (on exhibit there through December 31) on the theme of “The Magic City” rhyming the historic nickname for Birmingham with the visionary use of the term by Birmingham native Sun Ra, whose improvisational music on the 1965 record of that title celebrated an imagined place of balance and harmony where evil would be overcome and beauty be triumphant. Bailey’s new works also honor that style of balance, commemorating life transitions in characteristically oblique fashion and auguring a new blend of historical consciousness and personal recollection.

In speaking about Spiritual Migration, Bailey described his overall practice as being “like a self-portrait where I’m visually writing a story in space. There’s both fiction and non-fiction, but the stories I am telling could be true.” But Bailey’s quest to include what he terms “another level of history that allows viewers to find themselves in the work” has resulted in such things as, in the case of the paintings made for the “Magic City” exhibition, the incorporation of photographs of African sculpture from the Birmingham Museum of Art’s permanent collection, documented by Bailey himself in a series of visits. Bailey’s brand of hybridity is intensely personal, but it isn’t self-indulgent. His art deals deeply with African-American themes, but its emotional impact cuts across a fair number of cultural divisions.

Radcliffe Bailey, Saints, commissioned by the airport in 1996. [Courtesy of Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport]

Dr. Jerry Cullum, was Senior Editor of Art Papers Magazine, and now writes regularly for the ARTS ATL and a variety of other publications.