SOFT POWER

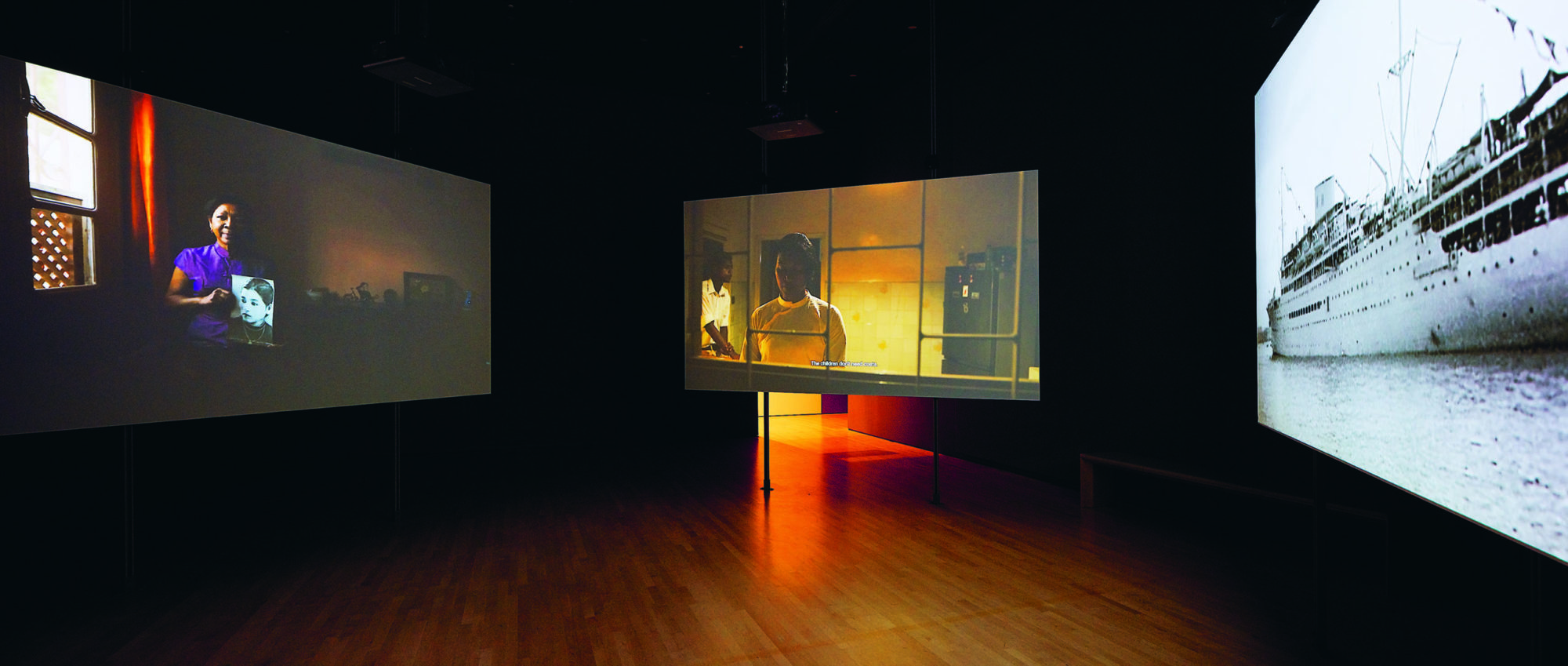

SOFT POWER, installation view, 2019 [photo: Johnna Arnold; courtesy of SFMOMA]

Share:

SFMOMA’s recent exhibition SOFT POWER was a sprawling assortment of conceptual artworks by 20 prominent contemporary artists. Works on view offered treatments of memory, place, politics, and migration from across geographies and social positions. They were connected through reference to “soft power,” a phrase adopted by the US State Department to describe its efforts to influence the developing Global South via cultural exchange and foreign aid. US empire, expressed this way, has become a sort of hyper-object beyond simple perception. It best comes to light in its negative effects—trauma, corrosion—and thus offers a compelling set of problems for artists.

Many of the works on view featured absorbing approaches to specific sites and narratives. I spent a long time studying and thinking about works by Pratchaya Phinthong, who offered a meditation on the American bombardment in Laos—undetonated bombs melted and refined into small mirrors bearing an impression of recovered Laotian landscapes—and Carlos Motta, who installed a series of videos about DACA’s impacts on queer artists. Motta also organized a conference on the topic hosted by SFMOMA and UC Santa Cruz. An engaging research-based artwork by Minerva Cuevas detailed the political ecology of the US–Mexico border through samples, maps, photographs, and film of the area in a true of mix of scientific and museological approaches.

Minerva Cuevas, “The discovery of invisible nature,” 2019, acrylic paint on wall [photo: Glen Cheriton; courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City; New York City; and SFMOMA]

But the main impression I had while walking through the exhibition was altogether different. The curatorial choices, in contrast with the situated politics of the artworks themselves, emphasized the works’ surface appeal. The presentation was, I felt, demonstrative of a widespread fixation among contemporary art museums on the aesthetics of commercial design and marketing: the depth of the work was obscured by an anodyne visual character. Upon entering the second floor, I was immediately swept up in vivid abstractions by Haig Aivazian, Eamon Ore-Giron, and Duane Linklater, all of whom employ organic forms and colors in their work. Aivazian, the Lebanese curator who has done work on dispossession, covered the walls in pink suede and a crafted menagerie of plastic animal forms. Nearby, Linklater’s works were laid out on the floor—tarps dyed in mauve tones with traditional Omaskêko Cree techniques using locally sourced pigments. Above them were four of Ore-Giron’s large canvases with perfect, architectural line-work over pastel gradients. I quite liked standing among these objects. And I liked the objects themselves, which thematized regional and indigenous traditions and, in Aivazian’s case, a colonial ideology of nature. The works shared a critical, anti-representational politics. But their assembly in the gallery denied this friction, reducing them to a mix of complementary colors and shapes.

All that these works seemed to retain was their currency as contemporary art. In an irony, such currency is a typical expression of soft power today. The arts reporter Sam Lefebvre recently wrote an article exposing SFMOMA board member Penny Coulter’s financial connections to military contractors (and making note that the museum gladly exhibited the recent Warhol extravaganza financed by now-infamous tear gas baron Warren Kanders). SOFT POWER, in this light, felt redundant not in its themes but in its soft concealment of political violence. It offered many of the contradictions that appeared at the 2019 Whitney Biennial, but without the controversy, the protests, the artist pullouts, or much reflexive engagement with the museum itself.

SOFT POWER, installation view, 2019 [photo: Ian Reeves; courtesy of SFMOMA]

Some curators are starting to realize that liberal claims of inclusion are exactly what make the global contemporary art museum such a potent instrument of deception—a kind of laundry service for the fortunes of war, private prisons, corporate drug trafficking, and so on. I do not envy the position of stalwart Eungie Joo, who took over as curator of contemporary art at SFMOMA in 2017 (after curating the Sharjah Biennial in the UAE, among other global blockbusters). Almost certainly a requirement of her job was to present this shapeless globality—and thus to flag the museum as internationally important. The late Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, perhaps the figure most associated with global contemporary art, has argued that such logics have come to absorb the discourse of resistance. He identifies the “paradox of a disjunctive innovation that simultaneously announces its allegiance and affinity to the very tradition it seeks to displace.”

This idea was fully evident in SOFT POWER, despite what I suspect Joo and the museum view as a continuation of Enwezor’s critical insights. Enwezor’s success had to do with bringing to light a new ensemble of practices—documentation, film, photography—from points of view that were not already overexposed. Perhaps privatized institutions in cities of the Global North are the wrong starting points for such inquiries. Efforts to gather voices from here and there have been widely contested for their tendency to exploit old colonial routes and to tokenize select artists. These contradictions should be thematized through a breakdown of the works’ transmission (from artist to gallery to public) so that audiences can better understand the institutional politics at play.

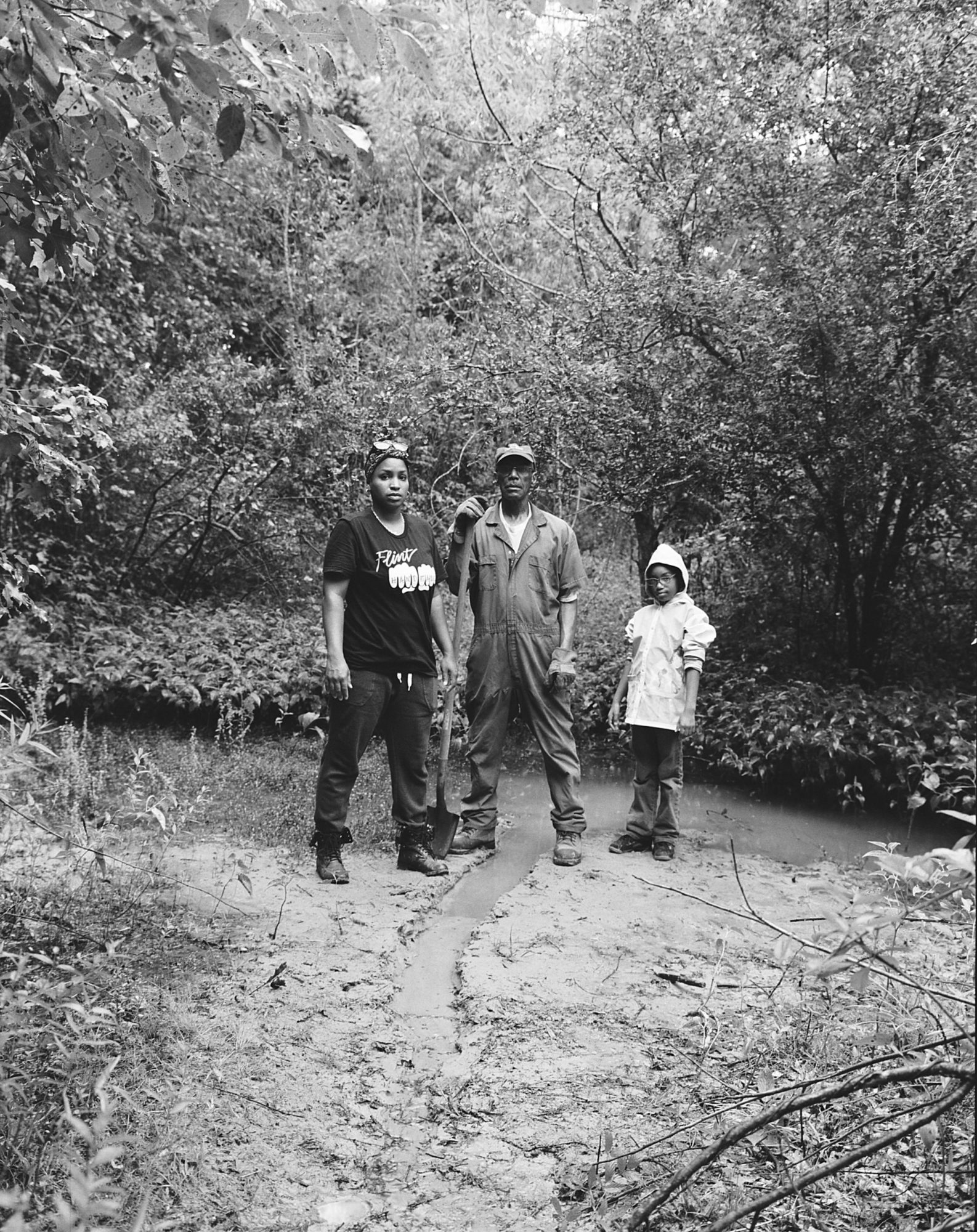

I will add in closing (and here’s another way of recognizing Enwezor’s influence) that the most compelling work on display was documentary in character. Motta’s installation in particular offers more than even journalistic outlets in elucidating the resilience of queer, migrant communities under threat. Cuevas’ work similarly exhibited the consequences of US expansion with rigor and detail. Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s work also offered some traction, transporting audiences from the gallery through a multichannel cinematic interface. Latoya Ruby Frazier’s work is, as always, a model for critical social realism in this country. Her visual exposé of a family’s flight from Flint, MI, to the deep South reminds us of globalization’s effects on poor people of color in a country founded on misery and privation—a realization that could also be made by walking outside the museum and into San Francisco, which bares all the signs of its own collapse.

Nicholas Gamso is the author of Art After Liberalism, forthcoming from Columbia Books on Architecture and the City. He teaches in the Art, Place, and Public Studies program at the San Francisco Art Institute.