The Last Frontier Left to Conquer:

Brief Reflections on Silent Running (1972)

Silent Running, 1972, screenshot [courtesy of YouTube and Universal Pictures]

Share:

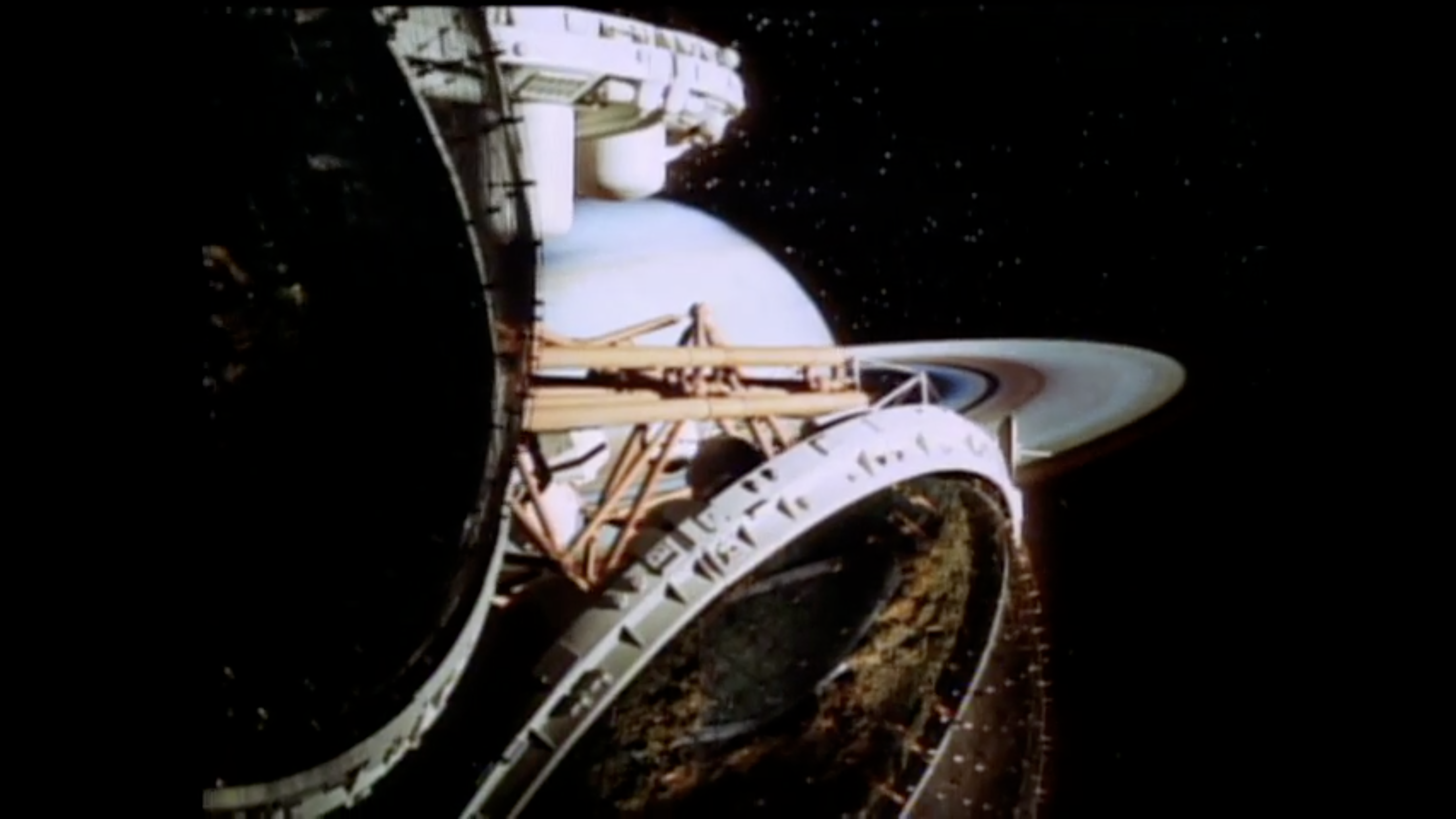

Silent Running, 1972, screenshot [courtesy of YouTube and Universal Pictures]

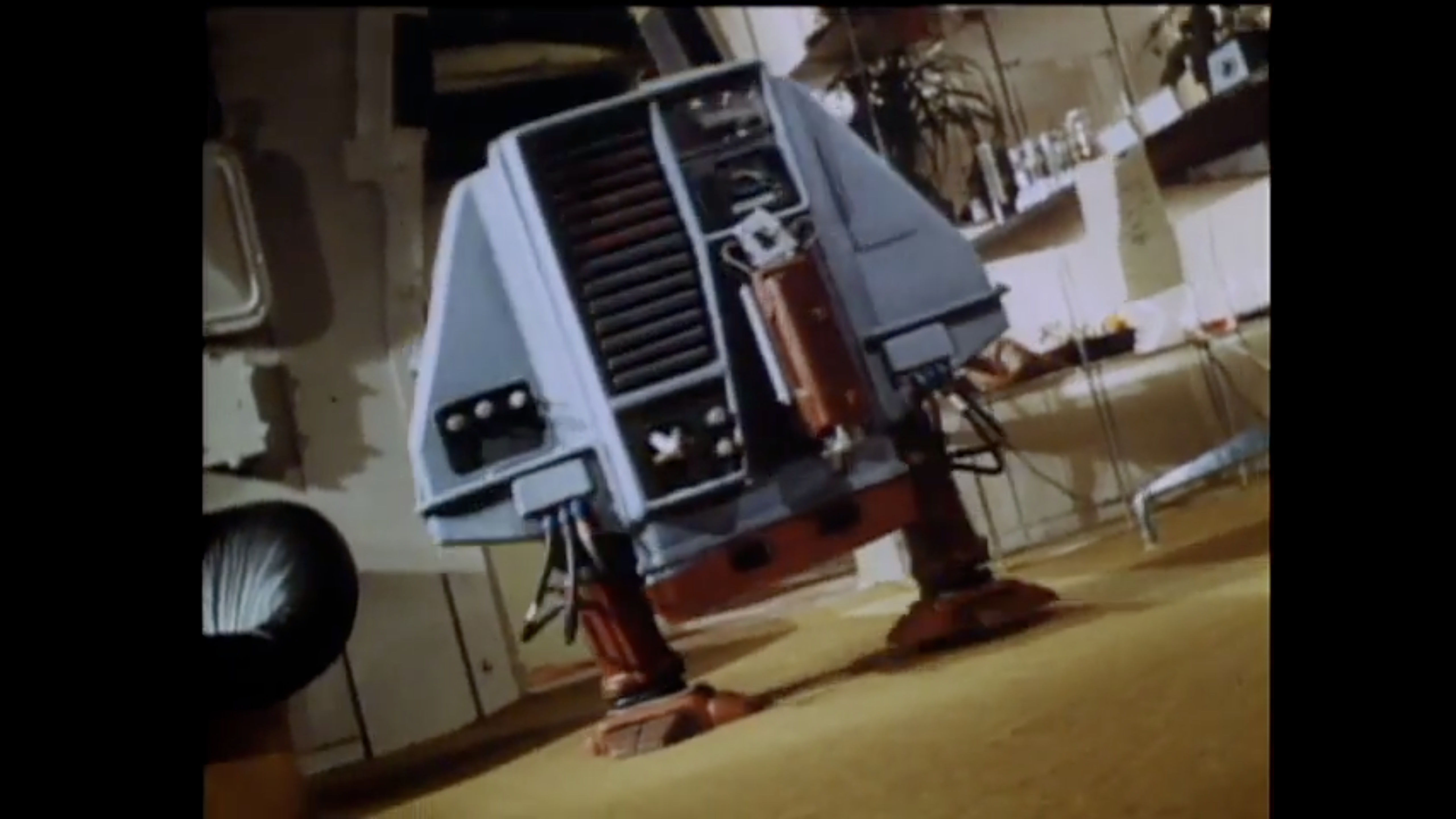

Silent Running, 1972, screenshot [courtesy of YouTube and Universal Pictures]

After emerging naked from a body of water set against a lush, natural backdrop, Freeman Lowell, resident botanist on board the spaceship Valley Forge, dons a priestly smock. This moment follows a sequence of closeup shots that track past snails, frogs, flowers, and leaves. Silent Running then introduces Lowell as a spiritual steward to the last remnants of plant life, which have been sent into space. A cataclysmic climate event has homogenized the temperature of Earth and wiped out all plants, save a select few that were enclosed within geodesic domes aboard the Valley Forge. The initial aim of the Valley Forge’s American Airlines–sponsored mission was to “re-foliate” Earth once its climate is reset by some feat of geo-engineering, thereby preventing the disastrous loss of life’s beauty and diversity, as Lowell repeatedly claims. Lowell’s spiritual disposition is jarringly juxtaposed against the mission’s proposed technological fixes. Silent Running’s premise seems to imply that a sustainable way of life cannot be achieved through radically revolutionizing earthly society—with its deeply ingrained, exploitative, and environmentally degrading habits. Rather, salvation is attainable only by spiritualizing those technologies aimed at managing and rationalizing living beings—and their environments—and by restoring balance through reinstating “Man” as the central figure. The spiritual dimensions permeating Lowell’s actions mask the American imperialist foundations that underlie the Valley Forge’s mission. Lowell, in his arguments with fellow crew members, explains that, on Earth, “there are no more frontiers left to conquer,” disclosing the colonialist mindsets of governance on Earth and their extension into space. With human action no longer confined to a finite Earth, expansionist ambitions find an outlet through the technical ingenuity of the Valley Forge’s sealed domes, stewarded by Lowell and his spiritual ethic.

Silent Running, 1972, screenshot [courtesy of YouTube and Universal Pictures]

The geodesic domes on board the Valley Forge were modeled—formally, technically, and conceptually—after the Climatron, a 1960 Buckminster Fuller–inspired dome, designed by Fuller’s student T.C. Howard and local architecture firm Murphy and Mackey, at St. Louis’ Missouri Botanical Garden. The Climatron’s four distinct climate zones—named Amazon, Java, India, and Hawai’i—were not separated by a physical barrier but by the thinness of air, with gradients of weather and temperature distinguishing them. Their names effectively communicated a colonialist and environmentally determinist disposition toward the very different tropical, colonial locations. Even Fuller endorses this reading of the dome as an image of control when he draws an etymological parallel between dome and domination or dominion. He writes:

“So important have domes been throughout men’s total experience that the root of the word for God, home and dome are the same—Domus, domicile and dome …. Because of the age-long interactions of mysticism, with religions of hope and fear, in the daily lives of men, always centering in the home, the dome, ages ago, became symbolic of all the cosmic thoughts, hopes, supplications and glorious conceptions. From its comprehensive pre-eminence, the dome conception gave root to the words dominate and dominion.”1

Silent Running, 1972, screenshot [courtesy of YouTube and Universal Pictures]

The Valley Forge domes, however, present a slight yet significant departure from their Earthly precedent. Whereas the Climatron relied upon a centralized climate-control machine called the Honeywell Supervisory DataCenter to monitor and regulate condition changes at different points within the enclosure, the domes of the Valley Forge replaced that device with the spiritual and benevolent figure of Lowell, tending to his plants and animals, ensuring the right conditions for their survival. The Climatron’s centralized control shifted from the paradigm initiated by its 1949 precedent, the Phytotron, at Caltech in Pasadena. The Phytotron consisted of discrete compartments, each with specific environmental conditions monitored and adjusted by a central “brain.” In contrast to the Phytotron’s compartmentalization, the Climatron achieved desired variations in environmental conditions with the aid of sensors and air-handling units within a single, open space. Both the Climatron and the Phytotron, directed by the same Dutch scientist, Frits W. Went, reflected a modernist impulse for total environmental control through the use of science and technology. In this light, the spiritual charge that Lowell presents avoids the loss of centrality of “Man” in an increasingly technocratic and mechanized society. His actions—killing the other crew members, resisting central orders, and stealing the spaceship—reveal the great lengths required to safeguard the integrity of “Man” while maintaining the trappings of an exploitative, colonialist, and capitalist society as tenable solutions for any possible sustainable future for life on Earth or in space.

Silent Running, 1972, screenshot [courtesy of YouTube and Universal Pictures]

Silent Running, 1972, screenshot [courtesy of YouTube and Universal Pictures]

Rami Kanafani is a PhD candidate in the history and theory of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. His doctoral research examines postwar architectural practices in the US that turned the whole planet into an object of representation and design. He investigates various institutional and individual attempts to foster a planetary culture within closed ecological systems that forged new relationships between humans, nonhumans, and the environment. Alongside an interest in the rise of environmentalism and its intersection with cybernetics, he also explores the relationship between the Anthropocene, posthumanism, and architecture history.

References

| ↑1 | Buckminster Fuller, “Domes—Their History and Recent Development,” in Ideas and Integrities (New York: Collier Books, 1963): 148. |

|---|