here. there. everywhere.

“here. there. everywhere,” installation view, 2020 [photo: John Stephens; courtesy of Sierra King and MINT, Atlanta]

Share:

How commonplace and easy it would be to truly love Black women if love were merely limerence, desire, and other ways that we have been admired, and then told, “I love you.” Sierra King’s curatorial statement for here. there. everywhere. at MINT calls the exhibition a dynamic love letter to Black women for the abundance of freedom they have introduced into the past, present, and future—or here, there, and everywhere. Black women are architects of freedom, and sometimes our only resources are a string and a wish. This exhibition was an empowering portrait of such architects. By actualizing Black futurity—made by our hands and through our distinct experiences—Black womanhood was represented in the exhibition through recurring themes of freedom, beauty, maternity, spirituality, hair, and food.

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors witnessed the delicate softness of Black womanhood in Natrice Miller’s Rebirth (2019), a series of portraits that captures this rarely shown side of Black women. The photographs arrested visitors not with color or clarity but with a blurred moment of whimsy. The subject wears a long, light-pink, chiffon dress. She is always in motion, sweeping her long black locs along her body. Rest and Revival are sweetly quiet. The subject’s hands are tightly clasped, held close to the body as if to keep some tiny thing safe. The photos, printed on translucent fabric and suspended from the ceiling, created a filter through which to glimpse the rest of the exhibition. These works positioned me here, and simultaneously framed other theres—other interpretations of the simultaneous nature of Black futurity that claimed Black futures while recovering Black pasts in the exhibition. Beyond Miller’s series of portraits, Humble Beginning (2020), a decadent culinary-themed installation by Mwandisha Gaitor—owner of the catering business 2 Pieces of Toast—was visible. In that work, silver platters hold framed photographs. Books, dried leaves, bright purple flowers, and cast-iron skillets cover the kitchen table, which is set for two.

Mwandisha Gaitor, “Humble Beginning,” 2020, installation view [photo: John Stephens; courtesy of Sierra King and MINT, Atlanta]

“here. there. everywhere,” installation view (right side), 2020 [photo: John Stephens; courtesy of Sierra King and MINT, Atlanta]

Coded (2020), a collaboration between Chandler Stephens and Jazmine Hayes, is a mural depicting heavy arching lines that lead to a knotted textile work made of Kanekalon—synthetic braiding hair used for a myriad of Black hairstyles. During my tour of the exhibition, curator and artist Sierra King said that Chandler Stephens’ other work in the show, The Powers That Be (2020), is an exploration of Ifá, a West African religion, most often associated in the US with Yoruba spiritual practices. The work included five minimal, uniform arches, nested one inside another, increasing in length and width from the inside out, painted directly on the gallery wall. The blue outer arches and the lower bright yellow inner arches called on Yoruba deities—Yemaya for water and Oshun for warmth. Yemaya, an Orisha, is of the ocean and creator of all life on Earth, as well as mother and guardian of Oshun’s children. Oshun, one of the most venerated Orishas, is of the river and associated with divinity, love, and fertility. Surrounding the mural were intimate photographs of domestic narratives. These images—most likely made by someone close, close enough to get the first photo of a newborn baby, the hesitant first dip of a toe into a cold pool, the child resting her head between the knees of the woman doing her hair—appeared to be family photos. Black women, here depicted as wholesome and warm, are often culturally stereotyped as caretakers, mamas, idols—which are sometimes careless labels, and sometimes deep contexts of association that connect Black women to these Orishas. Vernacular photographs such as those featured in Stephens’ work recurred throughout the exhibition, their presence alongside and within artworks elevating the potentially mundane to the status of an homage to Black women that spans generations.

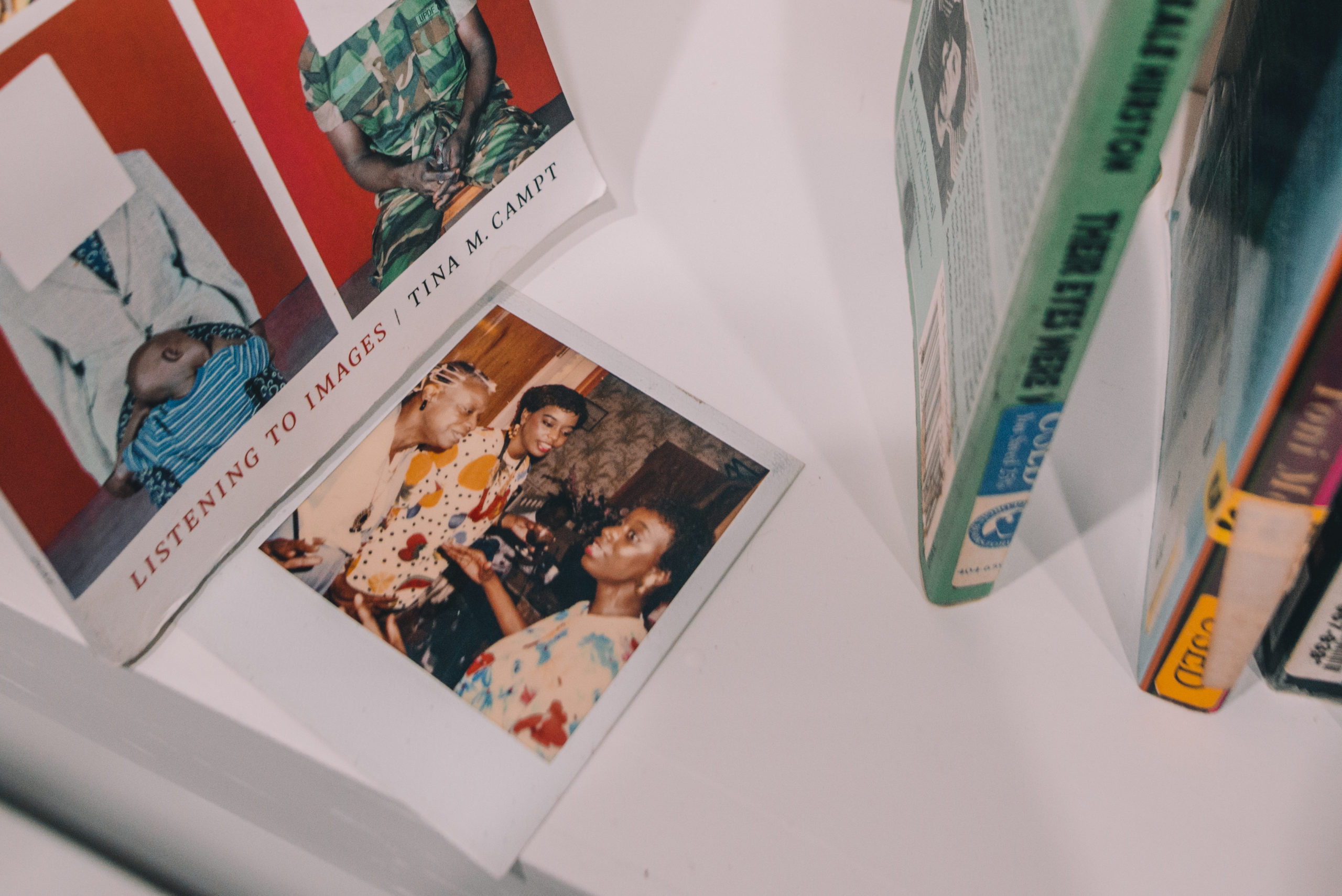

Sierra King’s personal archive, installed along the edge of the exhibition, is an assortment of photographs, books, vintage magazines, and cassette tapes. Visitors were invited to peruse these relics of her family matriarchs. Many of the magazines are addressed to King’s grandmother Ethelyn Stephens in Southwest Atlanta.

Sierra King, archival installation, 2020 [photo: John Stephens; courtesy of the artist and MINT, Atlanta]

Sierra King, archival installation, 2020 [photo: John Stephens; courtesy of the artist and MINT, Atlanta]

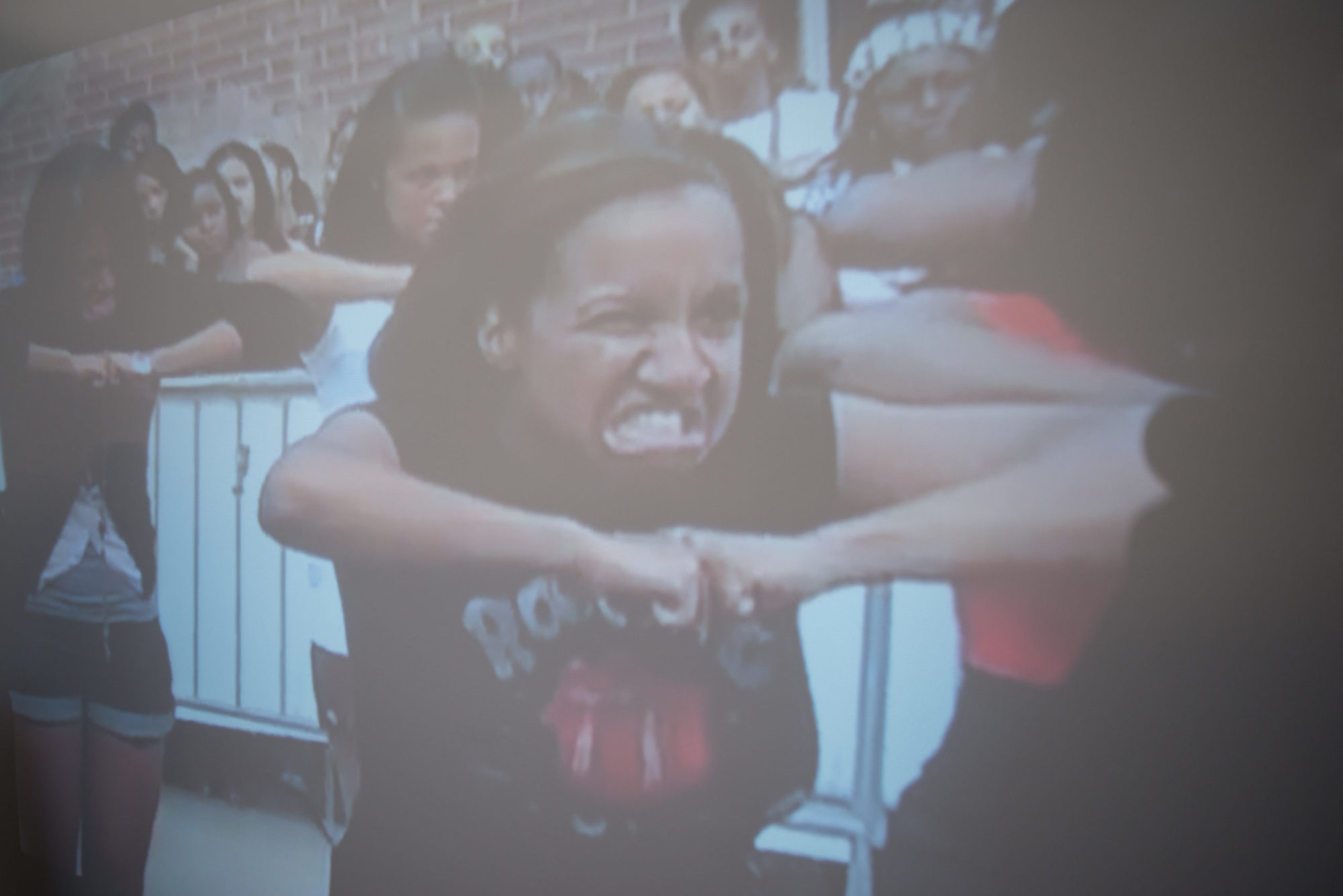

Jazmine Hayes’ video A Round of Applause (2019) is 5 minutes, 55 seconds in duration and uses video showing Nina Simone’s performance of “Four Women,” in which the stories of four Black women who embody several stereotypes are told. Hayes continues Simone’s humanization of Black women, beyond stereotypes, through a collection of appropriated videos that illustrate Simone’s lyrics. When Simone sings, “What do they call me?” the response comes from the audio of another video: “That’s Laquita, she does nails.” An effervescent, shameless voice interjects, “I would like to say that! … I do tattoos.” This comment made me smile.

Aypyhanie (2019), a painting by Toya Beacham, is a nude portrait of a nonbinary person whose pronouns are they, them, and theirs. Although artists’ pronouns and gender identities were not indicated alongside included works, the exhibition statement led visitors to assume anyone represented is a woman. Included artists pull from their distinct experiences of Blackness, Black womanhood, and Black futurity, and justifiably do not attempt to represent every experience.

Jazmine Hayes, “A Round of Applause” (still), 2019, single channel HD video projection (Edition 2/5), 5:55 minutes [photo: John Stephens; courtesy of Sierra King and MINT, Atlanta]

Testimonials, dreams, and the practice of love are at the crux of any effort toward freedom. Talk To Plants (2018), a video and installation by Ebony Blanding, shows a Black woman dancing in a light-filled building as she silently interacts with plants and glasses of water. This character represents Blanding’s grandmother experiencing dementia, but rather than inviting audiences to mourn her, the artist asked them to honor her and to touch and nurture the living plants that were installed below the projected video.

Many works in the exhibition—those of Blanding, Stephens, Hayes, and in King’s archive—incorporate intimate vernacular photographs. The ephemeral presence of faded portraits and group photographs in slightly blemished frames evoked the presence of family throughout the exhibition. There are Black girls, women, mamas, and grandmamas, all of whom this exhibition honored. here. there. everywhere. existed in an almost complete cultural void of gratitude for people with such an abundant impact on our community and world. The exhibition is significant not because it existed in spite of this void, but because King’s reverence and love for Black women was so present you could touch it, trace its contours, and feel it throughout the exhibition.

Taylor Janay Manigoult is an interdisciplinary artist and poet in Atlanta, GA. This year, they have been in Davion Alston’s project featured in fLoromancy, the UNMUTE series on Montez Press, and an installation—flowers within reach at the Goat Farm Arts Center—they created with Amber Bernard. In the spring, Taylor will be a resident at the Hambidge Center. Right now they are obsessed with their finsta, water, and keeping their Nike’s white.