Seriousness and Difficulty in Criticism

Barbara Kruger, Empatia, 2016, site specific installation in Mexico City Metro [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

Share:

This essay was originally published in ART PAPERS November/Decmber 1990, Vol 14, Issue 6.

In criticism one is often being serious about things which are by definition not serious. Works, that is to say, which are seriously not serious and difficult by not being difficult. Andy Warhol, for example, tried to fulfill both these criteria. Whether he succeeded or failed is a serious and difficult question.

It’s fair to ask, why is it serious and difficult? And the answer is, because art itself is important to us for reasons which are—guess what-—serious and difficult.

One way in which art is serious and difficult is that it raises questions which are unanswerable in more than one sense and all at the same time. It is simultaneously true that you can’t actually prove that a work of art is good, which is to say, art resists the regimes of logic and science. Nor can you prove that it means what you say it means. And that your idea of what it means might have to coexist in some way with a quite incompatible meaning which you will nonetheless not be able to deny—for example, Celine as fascist, and furthermore in some sense perhaps not quite a liberator— nor that it may be the case that your interpretation of the work is entirely wrong but conceivably so influential as to color the way in which the work is seen even by succeeding generations, so that you may in fact both be the one to recognize the importance of the work and the person responsible for consigning it to infinite misreading.

So the work of art, as has been generally argued since the time when the slave-owning societies which gave us the word democracy also gave us aesthetics—the ancient Greeks, in other words—is in a sense at the very least a kind of training ground for the very idea of difficulty, a kind of unserious zone where the serious might be properly considered as a form, difficulty turned into a game. This is what used to be called the aesthetic dimension of everyday life. In our epoch we have come to think or perhaps one should say the world labors under the delusion that this dimension is far more important than once realized. That contrary to the beliefs of Adam Smith and Karl Marx, it is not basic materials which count but luxury items. Late capitalism leaves heavy industry to the third world and concentrates instead on leading in the fields of fashion, popular music, high culture-areas of endeavor which don’t produce things which people can actually use, like cars or ships or even televisions and portable radios.

It is here that one encounters an historical curiosity. For it turns out that, as it has become clearer that true power lies not with production but with counter-production, with the useless rather than the useful, with the sign rather than the thing, so, paradoxically, has it come to pass that people are less rather than more prepared to see the work of art itself as difficult or serious.

My friend John Johnston was once teaching a course in literature at Queens College in New York and at the end of the first meeting a student came up to him and asked if this was a class in which one would have to read books. Infinitely patient, he explained that since it was a literature class an encounter with books, with, indeed, works of both fiction and non-fiction, was both implicit and unavoidable. I retell this anecdote to illustrate my point. We have reached an historical moment where the innocent feel that it is reasonable to expect access to cultural production without effort, and specifically without engaging the peculiarities of the form in question, which in Johnston’s case was and is the Book.

Possibly one could argue that people resist difficulty in criticism because what they seek in art is, precisely, relief from complexity. We are constantly being told, and only historians disagree, that the world at large is becoming more complex, that there are no straightforward questions left. Every time we think we have our hands on one, it ceases to be straightforward and becomes instead replete with contradiction. It is utterly unacceptable for Iraq to invade Kuwait, and with relief we invoke the principle of national sovereignty as one of those constants by which we live our lives, like the right of free speech. But the problem immediately becomes complex when we reflect that America’s primary ally in the region illegally occupies parts of all four of its neighbors’ territory. Is it that total annexation is unthinkable but partial occupation is all right? Or is it that annexation is only bad when Iraq is doing the annexing? Clearly a serious and difficult question rather than a serious but simple choice.

The point is that no one is surprised by such difficulty or particularly resistant to it. Nor is such acquiescence in complexity restricted to the indisputably com- plex issue of the moral basis of the foreign policies of democracies. In Los Angeles County, where I live, there is a drought, with the result that the populace is being encouraged to conserve water, the result of which is going to be an increase in everybody’s water bill. This is because saving water means that the water company sells less of it, and must therefore charge its customers more in order that its shareholders may persist in receiving their usual high rewards for doing nothing but having money to invest in other people’s need for water. No one, as far as I know, has voiced irritation at this apparent violation of the sacred principle which has it that it is the free market which keeps prices down and that prudent consumption allows the individual to save.

So on every front, foreign and domestic, one finds tolerance for difficulty. Except, apparently, where art is concerned. Here the story is quite different. Despite all the reasons—some of which I’ve mentioned—for recognizing that art and its criticism are difficult whether one likes it or not, a general feeling persists to the effect that it shouldn’t be. Or that it isn’t really difficult at all, but is made difficult by critics in the same way that ordinary people, with good reason, often suspect that the law is itself straightforward but is made difficult by lawyers.

There are, I should propose, three constituencies opposed to difficulty and seriousness in art and art criticism. These are the innocent, the left wing, and the right wing. The innocent, represented by the student who asked if she would have to read books in a literature class, are the most obvious victims of the historical conditions which have led us to substitute the idea of the consumer for the idea of the citizen. The citizen had responsibilities, not least among them the obligation to think for himself and to acquire the means to do so. The consumer is a pig at the trough, a recipient of nutrition who does not pause to ask what place in the food chain may have been reserved for him by those who provide him with food. The woman who asked whether she’d have to read any books was asking for education without effort, and in that reflected the triumph of the idea of consumption over that of struggle. Her argument didn’t reach the point of asking whether, if she didn’t read things for herself, and equip herself with the means to do so, she would pay a price for that. She was innocent of the need to think for herself, whence, perhaps, all intellectual difficulty derives, and wherein, as I’ve already implied, one consequently finds the primary argument for difficulty. Our answer to the resistance to difficulty enunciated by innocents, therefore, may be that art exists, not to destroy innocence, but to allow the innocent to find their own limits and in that to both expand and protect themselves, or the selves that they then become.

Turning now to the left wing, permit me to say at the outset that I am myself left-wing when it comes to politics. The total failure of instituted socialism to produce material wealth in the third world and the Soviet Union notwithstanding, I continue to see nothing wrong with aspiring to a society based on fairness and respect for others as opposed to greed and narcissism. Nor am I persuaded that Marx’s view of how history works has been superseded. A reliance on Marx’s categories has, however, proved to be more or less totally useless when it comes to analyzing the work of art. Among the reasons why this should be so, one would include the obvious truth that the work of art is an irresponsible phenomenon which is simply not reducible to its social origins. What this means is that the sort of things which Marxists tend to concentrate on don’t answer the more pressing questions we’re likely to ask of the work of art. Left-wing resistance to difficulty is founded in this truth, and is in consequence a resistance which tends to take the form of resisting difficulty by shrouding the analysis in another kind of convolution, the effect and goal of which is to attribute great significance to feeble and minor works which are nonetheless socially well intentioned while discrediting and short-changing complex and ambitious projects because they tend to be politically problematic.

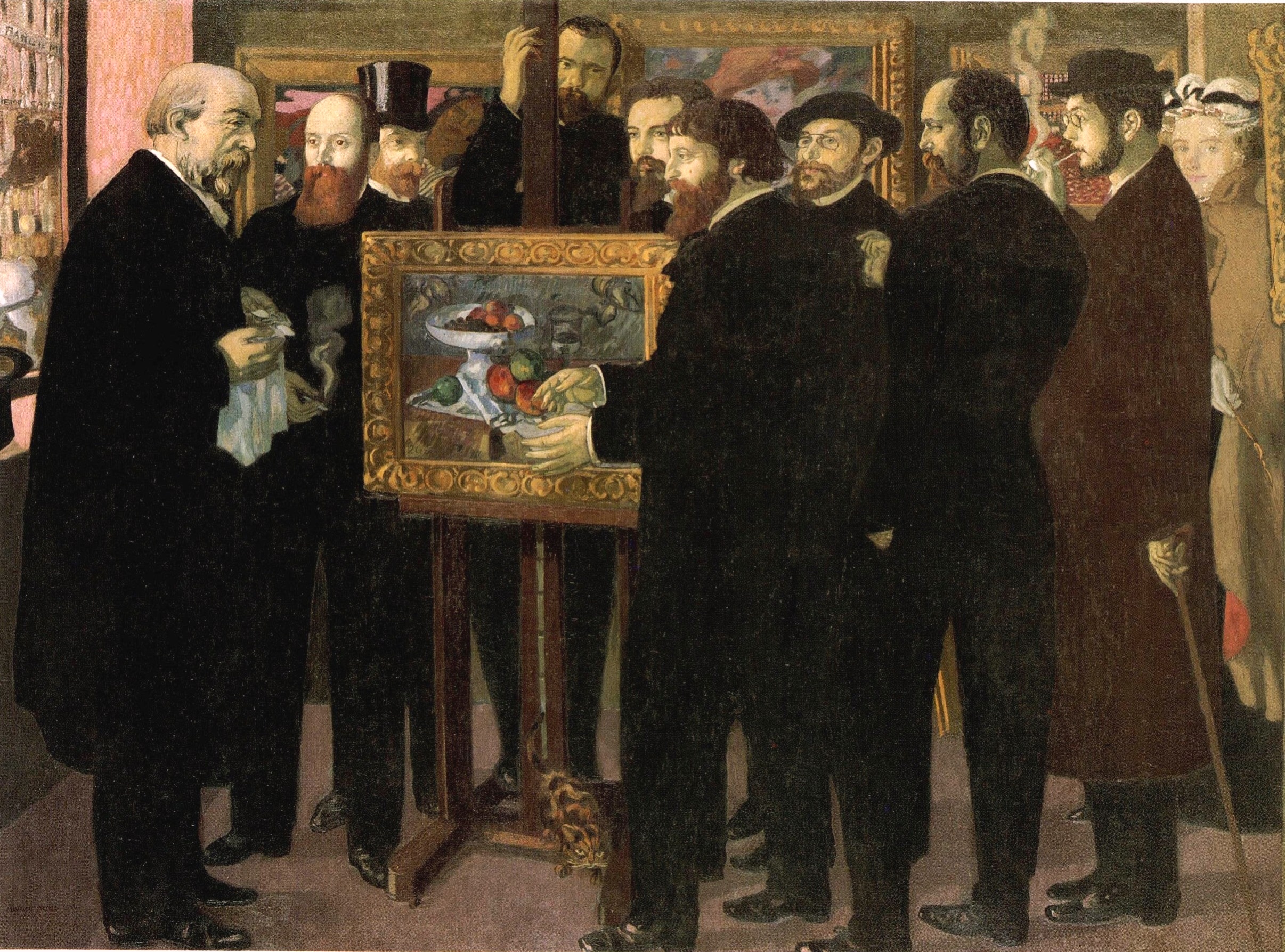

Maurice Denis, Homage to Cezanne, 1900, oil on canvas, 72 x 96 inches [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

The work of art is inherently irresponsible because it’s open to the possibilities available to the signifier when the latter is freed from the constraints of the signified. The work of art, in other words, plays with reality because it is not reality. The first people to get excited about this property of a work of art were the French Symbolistes, who as Penny Florence has explained were interested how in the work of art anything can be put together with anything because everything that occurs in the work of art is occurring in the world of signs rather than of things, so that the work of art resembles the dream—a place of apparitions and appearances—rather than consciousness, which responds to and occupies, to the best of its ability, the real world, ‘real’ being a word which derives from the Latin word for thing. The work of art can make things do anything because it is made not of things but of signs, a point which Manet sought to emphasize by painting things as if they were as much flat as they were solids, emphasizing thereby that they are signs for things and not things themselves. One sign may relate to—share space with—any other sign as one thing may not coexist, in reality, with any other thing, so that the work of art plays with the signifier in such a way as to create combinations which cannot, as I’ve suggested, be returned to a signified which makes sense in terms of a theory of meaning founded, as left-wing thought hypothetically always is, in an analysis of the real world, in, that is to say, the economics of the real. And thus it is that the left always ends up being frustrated by ambitious works of art, and accuses them of mystification, of being elitist. In fact those who made them never sought to mystify anything, in the sense of adding confusion to something which was in the first place uncomplicated, simple, and clear, but rather sought to pursue those possibilities inherent in signs, but which had not yet seen the light of day. In a word, to add to the world’s knowledge by stirring up the system upon which that knowledge depends. This, I am sad to say, is what the left wing cannot stand—and by the left wing I mean the left wing that we actually have, not the one promised by Benjamin and Adorno—the idea that there is knowledge to be gained, generated, played with, that is more a kind of ornamentation of the theory of production that they hold so dear, and mistakenly regard as a key to all that lives and breathes and to all that does not. As Baudrillard has shown, and as I hope I have now demonstrated, it is theories of counter-production which are called for by works of art, theories of irresponsibility rather than responsibility, of transgression rather than confirmation.

This is the sense in which the favorite works of the contemporary left are so arid, such trivial evasions of the difficult. The pieties of Jenny Holzer, expensively produced slogans offered as works of art, while directly comparable to the fatuous pieties of Mao Tse-Tung or the Ayatollah Khomeni, completely fail to generate anything like a new thought. What they do instead is exactly what the slogans of the Maoists or of Islamic fundamentalists do, which is to pretend that difficult ideas can be reduced to simple formulations. It is the insistence that such rubbish is the best that the culture can do which is so dangerous, the lunacy which has Jenny Holzer represent the United States at the Venice Biennale. That this could occur tells us that the worst has happened, that thugs of limited imagination have taken over the administration of culture in the name, of course, of liberation, just like Mao and the Ayatollah. This is a ritual abolition of difficulty and therein lies its danger. The abolition of difficulty is what consumer culture is all about. It’s not supposed to be what the left wing is all about.

And lest you think I am arguing here for an art of the amoral, let me say that if I am, it is not for an amorality which remains at that level, which as it were preserves the work at a level which evades the moral indefinitely, but rather for an amorality which leads back to that morality which would oblige its audience to assume responsibility for itself, to be citizens instead of consumers. On this point I am inclined to quote from an essay by a thinker who is by no means of the left but who cannot thereby be subsumed by the right, George Steiner.

“Whatever enriches the adult imagination,” says Steiner, “whatever complicates consciousness and thus corrodes the cliches of daily reflex, is a high moral act. Art is privileged, indeed obliged, to perform this act; it is the live current which splinters and regroups the frozen units of conventional feeling. That—not some modish pose of abdication, of otherworldliness—is the core of l’art pour l’art. This morality of enacted form is the centre and the justification of Madame Bovary.“

Barbara Kruger, Empatia, 2016, site specific installation in Mexico City Metro [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

This quote from Steiner is from a collection called, appropriately enough, On Difficulty and Other Essays. It is of course precisely the kind of morality which Steiner invokes and describes which is evaded by the works which arouse enthusiasm on the left. It is a morality founded in difficulty rather than ready made answers, and its renunciation by the left underscores the extent to which the latter is now simply a part of consumer culture. On the left as on the right, suppressing the difficult by advocating instead the most ridiculous simplicity is a guarantee of commercial success, which in academia means tenure and in the art world means that you get to sell your work. That these should be the goals and achievements of the left underscores one of the great truths of the Reagan era, namely that the powers that be have given cultural production to the left as a way of both keeping it quiet and simultaneously ensuring that it will become part of the Capitalist machine, willingly turning anti-Capitalism into a growth industry which develops new markets pandering to tastes which already exist and beliefs that are already formed. In this sense, as we know, there is no difference between providing of university departments which once never existed and which, once existing, cause us to wonder how we ever did without them, and products which invoke a similar response. How did we ever do without Women’s Studies, Gay Studies, Afro-American studies, or without computers, fax machines, and a telephone in the car? Small wonder that the language used to rationalize and justify the art favored by the commercial left should generally be so tortured; it exists to excuse the left’s participation in all to which it was supposed to be opposed. And, most terrifying of all, the left doesn’t know it. Drowning in sincerity, the commercial and academic left is the last bastion of unconsciousness, an unconsciousness which preserves itself by insisting that it alone possesses the key to consciousness. The left is the true heir of the Enlightenment, and what it has inherited is that mad belief in the mind as opposed to the body which led the Enlightenment astray and caused it to destroy itself, to never realize itself, and which now exists in such inadvertently parodic events as the career of Jenny Holzer—or Barbara Kruger, or Hans Haacke—or in such truly sad excesses as those acts of criticism that seek to persuade us that Leon Golub is an interesting painter or George Gissing an important novelist or Spike Lee, despite his many strengths, an inspired cinematographer. Whenever the left encounters anything truly interesting these days it shies away from it because it cannot immediately see itself in it. Thus do we now find narcissism where was once a methodology of liberation, profound conservatism which believes itself to be anti-conservative but which can never be anti-conservative because it is too sure of itself, too self-satisfied, too secure in its piety, in short, too conservative.

Hans Haacke, The Anatomy of the Horse, 2015, installation view [photo: Garry Knight; courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

And so to the third variety of resistance to difficulty, that practised by those who truly believe themselves to actually be conservative. If the innocent are, well, innocent, and the left is deluded in its belief that it can be opposed to the system even as it derives sustenance and power from the system, with which it really no longer has any quarrel at the level of the personal and the material, then those who actually call themselves conservative may be characterized, oxymoronically as it were, as both powerful and embittered. Like the left, the conservatives oppose difficulty on the grounds that they already have all the answers and that therefore what appears to be difficulty must in practice be willful obfuscation. Unlike the left, they are nowadays fully aware that, despite their immense power in the world, they are no longer in exclusive possession of power. The often heard complaint, advanced by the aging curmudgeons like Allan Bloom and young fogeys like Michael Brenson, that the humanities faculties of America’s universities are increasingly coming to be dominated by leftists of the generation of the nineteen sixties—my generation—is true. What this means in practice is that the fans of Jenny Holzer have more power than they should. But it also means that you are not going to be taken seriously if you insist that culture fell apart with the invention of abstract painting or the importation of ideas from France. Which is to say, it also means that conservative thought has become exposed for the fraud that it always was. As we know, conservatives in America—and indeed elsewhere—have seldom been interested in conserving anything. What they’re more typically interested in is egomania and instant gratification at any cost. Reagan was the great example of this, a man prepared to sell an entire country—this one–-to the multinationals in the name of tradition, and so it is with conservative criticism, which is prepared to bowdlerize the entire history of modernism in order to preserve symbolically what cannot be preserved in practice, the hegemony of the white male.

My son, Cyrus Gilbert-Rolfe, made the point in a review of Bloom’s book—The Closing of the American Mind etc. etc. etc.—that one big difference between young people of Bloom’s generation and the young people of today was that Bloom’s generation got to talk about casual sex and the young today get to do it.2 A remark which draws our attention to the extent to which conservatives are always infatuated by the symbolic, for while only getting to think about it, Bloom’s was a generation—perhaps the last one—which could seriously think about the world in exclusively male-centered terms. Blooms’ crowd never actually got any, but they could actually imagine an exclusively male-oriented sexuality, if ‘male-oriented’ is quite the right way—puns and double entendres are beginning to proliferate in this sentence to describe that particular fantasy. Of the three varieties of resistance to difficulty I have enumerated here the right wing one is the saddest and least serious precisely because it seeks to destroy not only the present but the past. Earlier art and criticism was never so brutish and straightforward as Hilton Kramer or Michael Brenson—Kramer’s protegé—would have us believe. If it had been it would never have survived, never have led to all that contradicts it but is indebted to it. I have made the point elsewhere that neoconservatism in politics is National Socialism without the working class component—a jingoistic, strike-free society ruled by an executive made up of politicians financed by giant corporations, like Nazi Germany but lacking the gruff beer-swilling aspect which guaranteed that the government would in fact make sure that the working class was well fed and well housed. In a similar sort of way, neoconservatism in art and its criticism is Modernism without the principle of change, a parody of the strained dialectic of a T.S. Eliot, and as such an intellectually trivial endeavor which, like Reaganism, implicitly proposes a total rupture, a radical break, between art as conservatives would now have it and the kind of art which an artist such as Eliot proposed, an art which sought to conserve its past through a sense of its discontinuity with that past. No one could take such nonsense seriously save those who were, implicitly, not serious.

To conclude, then, permit me to make a final point. I have suggested that resistance to difficulty in the work of art comes in three varieties: the innocent; the pious; the embittered. The point I should like to make is that while the innocent deserve our help, the left and the right deserve one another. There is, from the point of view of anyone actually interested in seriousness and difficulty, no significant difference between Andres Serrano and Jesse Helms. Indeed they need one another. Seriousness and difficulty, on the other hand, obviate both. They go elsewhere. So as to end on a note which addresses the needs of the innocent as well as obviating the cant of the pious and the embittered, let me conclude by suggesting that what we want from art is something like what Jean Baudrillard says he gets from theory: “It is true that logic only leads to disenchantment. We can’t avoid going a long way with negativity, with nihilism and all. But then don’t you think a more exciting world opens up? Not a more reassuring world, but certainly more thrilling, a world where the name of the game remains secret. A world ruled by reversibility and indetermination…”3

That is the world made by the work of art. Existing to disenchant the innocent, it offers reassurance to neither the left nor the right, but is instead thrilling. Its secret resides in its ulti- mate inexpressibility, its resistance to interpretation. Therein lies its difficulty, its irreducible seriousness. No wonder people resist it and the criticism it brings forth, it exists to destroy the world by endlessly reordering the names which give substance to things. And not content with reordering, it will even change those names or make them disappear, presenting us with that most threatening of all thrills, intelligible but nameless pleasure.

Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe was a contributing editor for Arts, writer on cultural issues, and advisor to the graduate program at Pasadena Fine Arts Center.