Reworlding

Share:

0.1

About a month ago, light years now for the living, millions of people looked up and saw an ultra-rare planetary event; the fleeting alignment of 4 bodies: the sun, the moon, the Earth, and perhaps even you. Through some impossible luck, I was in the Midwest, within the Path of Totality, giving a talk, and witnessed the full eclipse on a cloudless day. Many words have been tallied on the subject of eclipse events, and for those desiring some of the best, I would direct you to Annie Dillards’ essay, Total Eclipse from 1982. There, Dillard reveals, probably like many of us, that she too gleaned a partial eclipse at some point; the paper glasses, herding out of school, a black disk inching across the sun. It is amazing, but she identifies the essential psychic gulf between these two similar, but vastly different events. “A partial eclipse is very interesting. It bears almost no relation to a total eclipse. Seeing a partial eclipse bears the same relation to seeing a total eclipse as kissing a man does to marrying him, or as flying in an airplane does to falling out of an airplane. Although one experience precedes the other, it in no way prepares you for it.”

Casting aside the quote’s creaky normativity, this is close to what I experienced. Even arriving “prepared”— having seen the charts and images, knowing the science—how could I, along with a field full of abiding adults, transform instantly into a howling, screaming mass? Shouting at the sky? The scope of the experience simply—profounding—exceeded me along with my science-addled rationality. The shouts were of a welling over, evidence of an alien event glitching our collective brains. Surprise seems too small of a word, but I was consumed by it. Were the cries released from my body the result of the moon’s shadow leaking into my retinas, unlocking some hidden vault of animal knowledge? Was I being newly cleansed for my next years on Earth, or cursed in this sudden and unearthly night-for-day reversal? Three minutes and 37 seconds later, the sun’s light returned to normal, but nothing was normal. Some essential difference remained.

1.0

Spiritually aligned with these concepts—people, earth-scale events, immensity, the possibility of renewal (or not)—finds our issue’s theme; Reworlding. Sitting adjacent to the more out-of-time concept of world, much has recently been written of planet, the planetary, and even planetarity; a term postcolonial theorist Gayatri Spivak coined to help liberate us from previously de rigueur concepts global, and globalism. This recent planetary turn has been underwritten by a rising agreement that the interconnected “flat world” espoused by the blanched oracles of globalism was, in fact, something of a long-form, earth-scale parlor trick—one sadly lubricated by supply-chain-loops propped up by racist, para-colonial logic, supporting a pipeline of mostly southern extraction to northern consumption.

In the wake, we’re now inheritors of horrors flowing to us both upstream and down: arriving from the fever dreams of vectoralists and technocrats in the form of products, substances, and new molecules we never wanted that melt our brains and bodies and cells; and from an Earth in rebellion, cooking up pandemics and new climate as an antidote to these manic desires. For lay people, we’re in the middle, caught spinning in a vortex as these energies collide and swirl; an undercurrent slowly dragging us out to sea.

What might this have to do with art? Artists? I would argue, just about everything. The process of considering the macro reality that our bodies are cast within is part of an ancient story; an arc as old as humankind that artists have been the de facto fablers of. World is a primary protein of an artist’s diet. It’s the shared, ineffable medium of our work. It’s also the cauldron we can’t escape from, trying as we might to register all the tastes, all the vibes and feels, to sing back our findings, before being boiled alive. What separates us, the living, from our recent ancestors, is that we have inadvertently become not just people of the planet, but planetary people. And as planetary folk, we’re the generational interlocutors of interlocking, simultaneous and earth-scaled challenges—something called the polycrisis.

Ben Davis, using this concept as a backdrop, recently opined that “the shocks are not shocking.” This observation might be right, and if it is, it manages to create a double bind—for just as we’re cast in the throes of Earth-scale calamities that need collective attention, our brains and bodies are toggling into self-preservation mode. We are unmoved, incapable of moving, purposefully checked out, or dug into deeper pits of deep-fake denial. The sentiment maps on to how many are feeling privately about art these days; the habit continues, but the shopworn approaches we’ve been handed down—ones honed to perfection within the late-stage globalist bubble—seem unable to siphon adequate durations of attention for art to culturally matter outside itself. Or, more pointedly, are we reaching a phase, where knowing what we know, art begins to feel impossible amidst panoptic crises.

A chasm is opening, and a planetary malaise may be seeping in, radically altering our cosmovisions, our imaginary of Earth, and how to live. The intensification of the process is reshaping our imaginations for what is possible: the contours and brightness of our dreams. This ever-fertile site of possibility, recovery, and new-normaling is where we will linger in this collection of texts. If there are other worlds, they only exist within this one, within us.

This thematic, of course, doesn’t trap itself by offering faux remedies for fixing a busted-up world. Toward this, Gean Moreno and Stephanie Wakefield’s ’s brilliant text casts a lens on Miami, but pulls focus revealing a wider, weirder kaleidoscope of climate mitigation strategies, resilience officers, forecasting reports— describing a world where our ability to imagine is consumed by a logic of omni-crisis, one that artists are readied to visualize.

Artists Haley Mellin and Timur Si Qin contribute a roaming conversation that weaves belief, art’s practice, spiritualism, conservationism, and the tangible ways that artists might wield their powers beyond critique, utilizing the machinations of art toward critical change at planetary scale.

Artists, being transformers of matter, are intimately bound to Earth’s storehouse of materials. Del Harrow offers a poetic text that connects us to how artists obtain a foundational substance: clay. Harrow weaves the industrial process into an ancient feedback loop, one where we discover that the act of making objects with earthen material developed our capacity, as beings, to think and remake again. We’ve come into ourselves through the intimate and ancestral touching of Earth, bringing matter—and ourselves—into form.

For the issue’s glossary, the brilliant Sophie Strand contributes a delicious musing on the term Ecotone; a transitional zone between two biological communities, in the poiecis, finding resonance for the way our bodies might mutually transform, recover, become in the overlaps of others.

Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe has mused matter of factly that “a key driver of the process of planetarization is capitalism.” This concept undergirds much of Stephanie Bailey’s generous offering, which counterintuitively delivers us back to the inchoate animal origins of global capitalism: 18th century whaling. As a haunted through line, Bailey calls upon Melville’s Moby Dick, casting the whale as a willful and vengeful agent of a natural world in rebellion.

Conceiving the term “reworlding” as an active verb, perhaps the most productive site we have for renewal and world building—for better, and as of late, sometimes worse—is school. We gathered some of our moment’s most gifted and celebrated artist-teachers: Angela Dufresne, Gordon Hall, Arnold Kemp, Aki Sasamoto, Nato Thompson, and Rodrigo Valenzuela for a conversation that explores the aspirational promises, pitfalls, desires, and possible new chapters of teaching art.

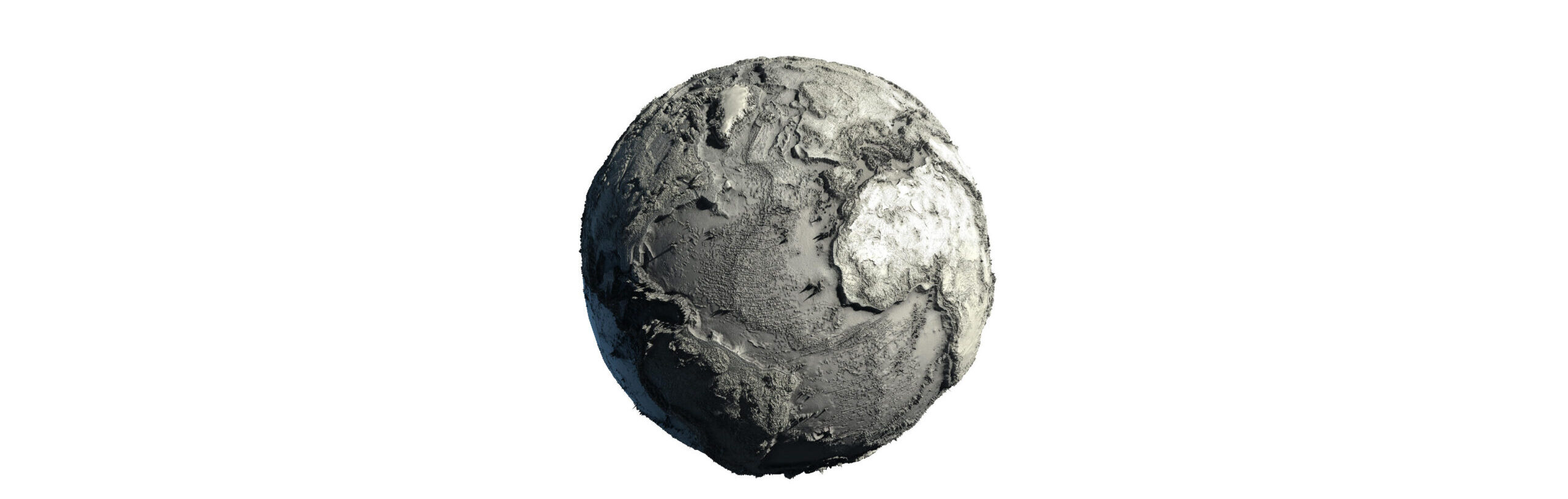

Finally, seated within the tradition of artists writing, I contribute a discursive text into the mix; it’s specter, an artwork I’ve been making since 2017, Twelve Earths. It is a tremendous gift to be offered space and time to ground some longing floating ideas into form.

In nearly all the commissioned works, the implied scope and complexity of “world,” beaconed many writers beyond the realm of traditional word counts. Said plainly, the texts got longer—but I think deliciously so. In receiving the pieces back for editing, each landed with a generosity of thought and spirit that in broaching the formal bounds of the commission, also leaned into personally inspired realms. Zones where word counts be damned. There is of course a logistical side to hosting more words, and I must thank Art Papers’ staff, and especially Sarah Higgins, for holding a space for artists and thinkers to explore the depths of ideas. I encourage you to come along for the ride.

-1.0

Baked into the idea of reworlding could be the tacit understanding that an “unworlding” has happened, or is happening. An event, or events, that have untethered us from a past world, one we have grown tender attachments to, and one that, in its passing—even as we are challenged to heal and collective rebuild—we are still grieving from. With this in mind, it’s important to linger for a beat on the history of this publication: Art Papers. As you read these lines, for the first time in almost 50 years, you do so without a printed volume traveling in parallel within the world. In this issue ‘Papers’ exists now as a vestigial metaphor, belonging to some other world. One I, and I know others, will miss.