Reckless Rolodex

Reckless Rolodex, installation view, 2023, (courtesy of the artist and Gallery 400. University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago)

Share:

The January 17, 1997 episode of This American Life—hosted by Ira Glass, on the Chicago-based NPR-affiliate radio station WBEZ—featured “stories of starting life over.” In Act II of the program, performance artist Lawrence Steger reads, in monotone, a treatment for a screenplay about Luke—“Gay, white, Midwestern, late twenties”—on the day he is about to embark on a road trip with his friend Bill. But Bill first discovers, at a clinic, that he’s HIV positive. Luke is a fictionalization of Steger, who also planned a cross-country trip right before being diagnosed with HIV in 1990. The flat affect of his voice and directorial tone is in jarring contrast to the emotional content of the scene, although it also speaks to how the spread of HIV/AIDS and the governmental neglect of its victims had, by the 1990s, made the epidemic in the queer community seem somehow ordinary—tragic, yet banal.

Throughout his narration, Steger makes reference to—and revises—the script, especially the soundtrack: “Can we nix that Strauss music? It’s kind of too mournful. There’s really no music on the soundtrack. It’s stark, crisp, maybe some songs coming from the radio at the clinic’s desk.” Steger is trying to find the right emotional genre for the atmosphere of an epidemic. The elegiac is too on the nose. Once again, it’s the banal that triumphs, the ordinariness of a radio tuned to an inoffensive channel in a waiting room.

Steger, who died two years later of complications from AIDS, at age 37, was the subject of what is best described as a tribute show at Gallery 400, a space that is open to the public and run by the University of Illinois, Chicago. Titled Reckless Rolodex, this exhibition, like Steger, was trying to find the right tone for the death not only of an individual but of a population disproportionately affected by a condition exacerbated by public indifference, as activist groups including ACT UP—with which Steger was affiliated—made clear. It was therefore fitting that, in a bold choice, this exhibition devoted to memorializing Steger did so not by restaging parts of his oeuvre but by displaying more recent works from Chicago-based artists who carry on his thematic concerns, interventionist techniques, or political ends.

Reckless Rolodex, installation view, 2023, (courtesy of the artist and Gallery 400. University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago)

Although he was born in St. Louis and briefly resided in New York, Steger’s life, work, and community was Chicago, where he attended SAIC. He was a regular performer at cabarets, theaters, and artist venues, sometimes staging his own plays; sometimes narrating a film he had in his head, like what he would do on This American Life; and sometimes lip-syncing in drag, especially songs by Yoko Ono, about whom Steger became a nonprofessional expert. In an excerpt from Steger’s journal, now available in Matthew Goulish’s exhibition companion—printed in a first edition of 450 copies by Cold Cube Press and freely available for viewers to take home—the artist explains that he was “trying to write and make theater that is alive and honest to [himself] without invoking pity or mercenary reactions.” These works were, like all performances, ephemeral by nature, even as they provided the infrastructure to sustain a larger queer community.

Steger’s works themselves, or video documentation of them, were entirely absent in the Gallery 400 exhibition, save the audio recording from This American Life, which was available via iPad and headphones in the exhibition’s final room, alongside ephemera from his life and career: magazine articles covering one of his shows, programs and fliers for group exhibitions, backstage photographs. One way of thinking about this exhibition design is that it made Steger’s presence spectral, let him haunt the scene of his remembrance through ghostly absence.

Another way to think of the design is that it captured something central about the AIDS epidemic, which is the sublimation of the individual into community, the dead into the sea of mourners. Dominating the largest room in the Gallery 400 exhibition was a humongous stage designed by artist Edie Fake. It rested just a foot above the floor, was designed like a board game, and served throughout the exhibition’s run as a platform for performances and other events. The work actualized how art can become a vehicle for a community by providing a space for gathering, as well as a space for making yet more art.

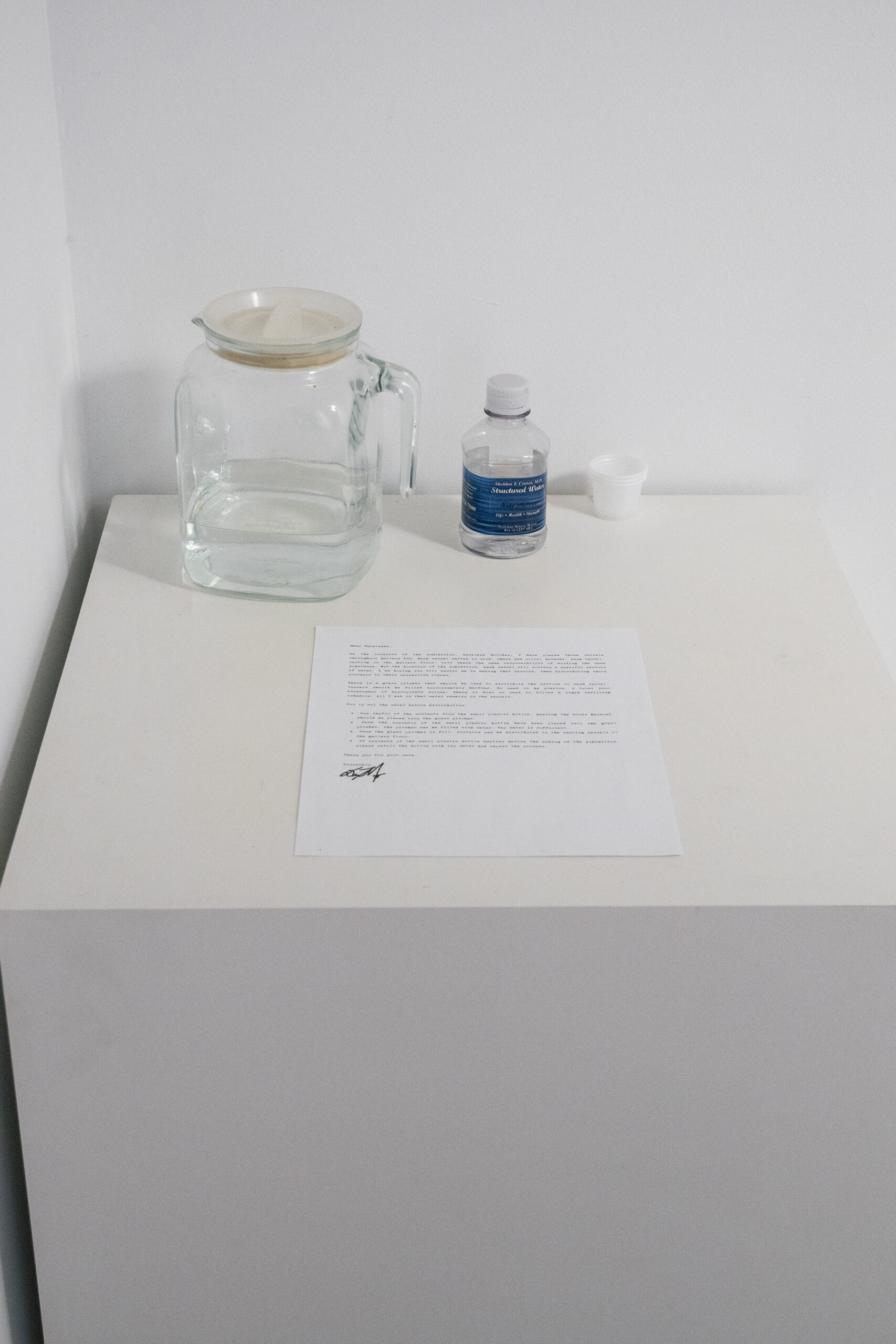

Devin T. Mays, At rest, a vessel, 2022, vessels, water (courtesy of the artist)

Reckless Rolodex, installation view, 2023, (courtesy of the artist and Gallery 400. University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago)

A third way of thinking about the exhibition design of Reckless Rolodex is that it, like Steger’s monotone narration on the radio, was more about emotional atmospheres than about singular events, such as a death. It presented ways that disease, social stigma, marginalization—and resilience, survival, and social subversion—are lived ordinarily, not just in the register of the funeral or on the calendar that singles out one date for World AIDS Day. Hanging from the ceiling in the first room was Young Joon Kwak’s Brown Rainbow Eclipse Explosion (2017), a fragmented sphere of a chandelier that is, at once, a shattered disco ball and a blown-up planet from a science fiction movie. The artist describes the work as an “open-ended sort of choreography, expanding our sense of what our bodies can be, what they can do, how they can feel.” A disco ball scripts its own choreography—the right moves to showcase on the dance floor—whether to let go of the day’s problems or to find that night’s hook-up. But when the ball shatters, dancers are left to improvise a new movement forward, a different rhythm that is nonetheless, like all dance routines are, communal.

Young Joon Kwak, Brown Rainbow Eclipse Explosion, 2017, cast aluminum, welded aluminum rods, resin, glass mirror tiles, acrylic mirrors, epoxy putty, acrylic paint, motor, steel chain and hardware, custom LED light, shadow (courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles and Mexico City)

Scattered on the floor throughout Reckless Rolodex were plastic basins of water, part of Devin T. Mays’ installation At rest, a vessel (2022). As the water evaporated throughout the duration of the installation, gallery staff were instructed to refill the basins from a glass pitcher the artist left, like a statue, on a pedestal. This transubstantiation of water into air ritually reminds us of our shared atmosphere, an allegory not only of “ashes to ashes”—that the bodies of the dead live on in the planet’s dust—but also of the singular becoming shared, a life becoming public, a biography becoming an ethnography.

This thematization of air couldn’t help but take on new resonances and anxieties in a contemporary gallery where all patrons dutifully wear masks, just as the ongoing public health crisis of AIDS has provided analogues for the new crisis of Covid-19. In the second room of the exhibition was an installation, from Derrick Woods-Morrow, titled Gravity Pleasure Switchback (2023). Two used mattresses stood upright and opposite each other, embedded with subwoofers that played a looping nightclub beat. Dispersed around them were balloons; between them was a helium tank, but viewers were also invited to blow up unused balloons with their breath and leave them on the floor. The materials list on the gallery label included “balloons filled with human breath and helium” alongside “empathy, patience, and time occurring naturally.”

Derrick Woods Morrow, Gravity Pleasure Switchback, installation detail, 2023, used mattresses, natural stains, subwoofers, balloons filled with human breath and helium, looped 8:57 mins. audio track, as well as empathy, patience, and time occurring unnaturally (courtesy of the artist and ENGAGE Projects, Chicago)

Empathy may have been one aim of Reckless Rolodex—or, rather, an empathic connection to the past. If Woods-Morrow’s balloons staged for us a being-together, even amid social distancing, in a world where breath has become both symptom and vector of an epidemic, the used mattresses and audio track also staged for us the now-evacuated dance floors of yesteryear. These dance floors are forgotten not only by straight society but also by the canons of gay art and culture that overwhelmingly prioritize New York or San Francisco. The irony of Steger’s appearing on This American Life is that, even as the Midwest is sometimes taken as a metonym for “American,” queerness is oddly considered neither American nor Midwestern. And for a younger generation of queer people, less intimately connected to the carnage of AIDS, the index of breath may provide a means of learning about a shared past and space.

An article available in the collection of ephemera in the exhibition’s back room quoted Steger as saying: “When you’re fucking, you slip out, somebody farts, whatever.” Steger was interested not only in the main event but also in all the accidents and crap that happen in its orbit. So, too, was Reckless Rolodex not so much about the man but the world to which he belonged, or what can be revived of that world a generation later. Following Steger, the humor of many of the works, as well as the cleverness, built that world at the level of mood and atmosphere—the farts and whatevers.

Michael Dango is an assistant professor of English and Media Studies at Beloit College. He’s the author of Crisis Style: The Aesthetics of Repair(Stanford, 2021), a study of how contemporary U.S. art and literature responds to a pervasive sense of crisis, as well as the forthcoming 33 1/3 series book on Madonna’s Erotica.