Rami George: The Tangents, Pivots, and Slants of Artistic Research

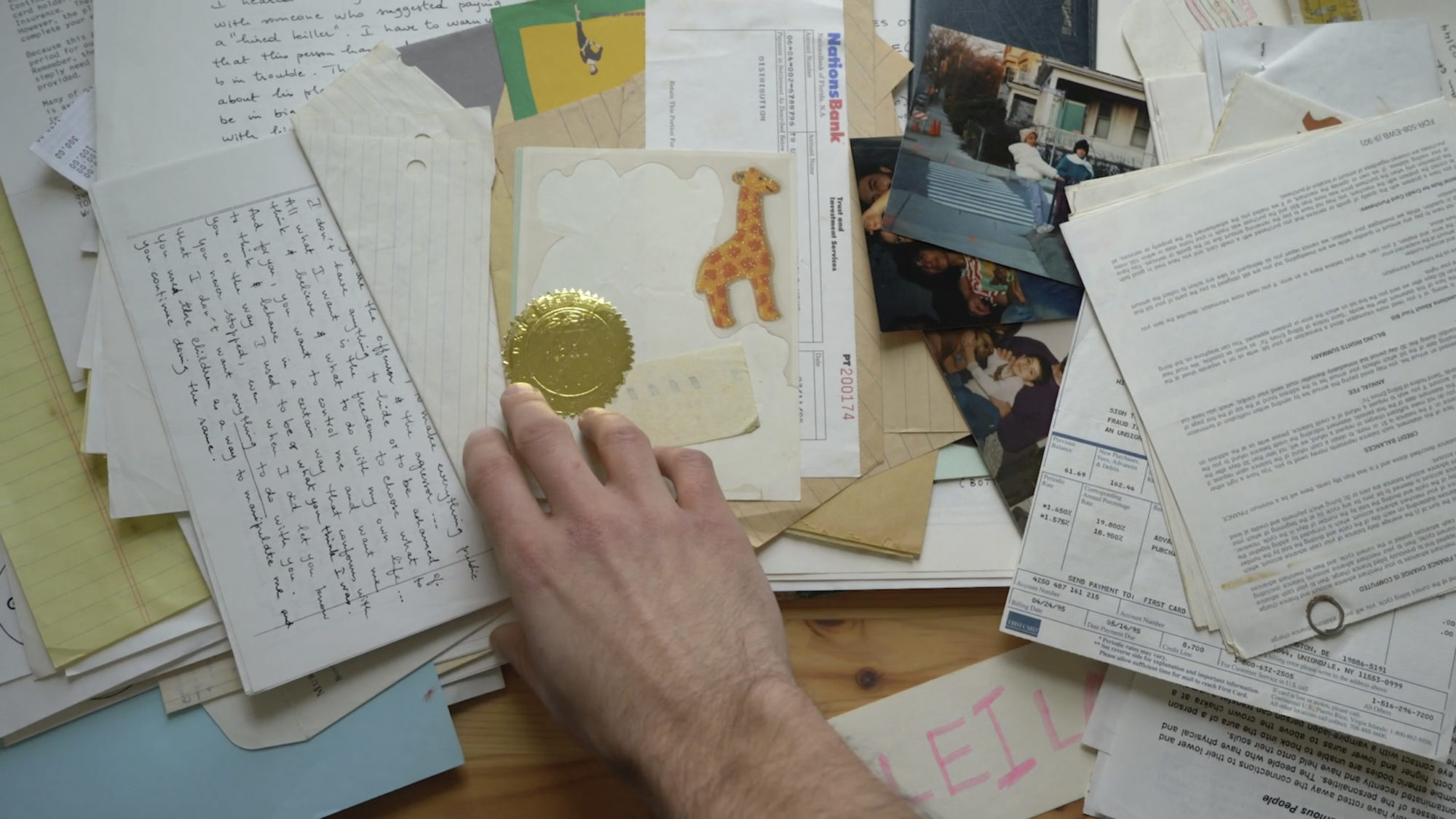

Rami George, Video Playlist (composite video still), 2020. HD Video, color, sound, 41:30 min. © 2020 Rami George. Image courtesy of the artist.

Share:

Rami George’s video essays, installations, sculptures, and collages teem with references to the artist’s conflicted encounters with the Samaritan Foundation and, most recently, the ashram known as The Movement Center in Portland, OR. The Samaritan Foundation was a New Age intentional community, or cult, in which the artist’s mother became deeply involved in the early 90s, ultimately leading to a custody battle over the artist and their sister, and to the children’s forcible removal from the community. The Movement Center is another intentional community of which the artist’s father has been a member for almost 50 years, and an entity with which the artist engaged throughout their adolescent years. George’s video essays function as citational threads, tethered to, and interwoven within, the stories of these communities at varying scales. The artist’s intricate research process radiates from narratives of history writ large and zeroes in on often-sidelined personal and familial accounts that impress themselves upon the psyche. As George describes, this tracing, or footnoting, follows a sinuous journey through tangents, pivots, and slants.

The following conversation encompasses several forms—including transcripts of recorded talks and Google Docs—produced throughout 2020 and 2021. George and I recall cogent research points that unfolded during their solo exhibition List Projects 21: Rami George at the MIT List Visual Arts Center [March 19–October 11, 2020], their participation in the

group exhibition Networks of (Be)longing at the Center for Contemporary Art & Culture (CCAC) of the Pacific Northwest College of Art [October 16–December 6, 2020], and their satellite show, Rami George: and one day will tell you so many stories at Paragon Arts Center of Portland Community College, Cascade Campus [September 25, 2020 spring 2021]. In the midst of conflicting global and national narratives, George’s research expands and contracts; pushes and pulls against dominant frameworks of selfhood, community, and home; and repeatedly returns us to the intimate knowledge and power of the personal.

Rami George, Still from Untitled (with my father), 2020, HD video, color, sound, 20:31 min [© 2020 Rami George, courtesy of the artist]

Laurel V. McLaughlin: You’ve mentioned the importance of research within your artistic practice. “Artistic research” is a somewhat nebulous term, so, how are you thinking about it?

Rami George: There are different types of artists, of course, some of whom are more studio—and others more research—based; I feel that I take a bit of both, but that the research acts as a sort of backbone to it all. Having gone through academia, I learned traditional research and writing strategies, but I found that I wanted to get weirder. I love the flexibility and porosity which is artistic research. Being able to pull from many different things or events or histories—some clearly connected, others less evidently so—and being able to hold them concurrently, there’s a special freedom and gift in this, and I do believe it can lead to new, and potentially radical, discoveries.

LM: And it seems to be influencing more “traditional” modes of scholarship—and academia needs that desperately. The porosity and flexibility which you infuse [into] your research extends to how you situate “autobiography” in relation to your work, especially in your video essays that explore your entanglements with the intentional community the Samaritan Foundation in Untitled (Samaritan Foundation)(2014), Untitled (Saturday, October 16, 1993) (2015), and Untitled (with my father) (2020). How does your personal perspective stretch the histories of this community?

RG: I think autobiography has been part of my work from the beginning, but the naming of it as such has been more recent—specifically by Selby Nimrod, assistant curator at the List Center, in writing about my practice for our exhibition. With the naming, then, comes a parsing of the history of the genre—what are its strengths, what are its limitations?

Like much of my research, the process begins in reading, writing, collecting, and sifting. It’s been a particularly unique experience to find my name in print and pre-existing publications related to the Samaritan Foundation community. And, like all research, one thing leads to another. For instance, researching the Samaritans has led me to explore other intentional communities of the time, such as the Branch Davidians in Waco, TX—to which the Samaritans were routinely publicly linked, although my mother says this was mostly inaccurate. Like other forms of research, it feels like the discoveries expand and contract, and ultimately I get to decide what to funnel down into the specific project at hand.

I think that by starting from a place I know—the personal, the self—I can then circle around larger local and global narratives, while still feeling deeply invested in the work. I do believe that autobiography, or even just personal anecdotes and experiences, have the opportunity to destabilize set narratives. In many ways, Untitled (Saturday, October 16, 1993) and Untitled (with my father) are the same story, but the modes of telling are quite different—a public media version in the former, and a personal lived experience in the latter. I hope that by allowing them to sit alongside each other, ideas of truth and history are pulled at in generative ways.

LM: Within your research there seem to be a few concepts around which you repeatedly circle, such as narrative, assemblage, and affect. Beginning with narrative, how does it figure within your research?

RG: I was able to share Untitled (with my father) with my father, and we’ve had a lot of conversations about the work and my practice in general. He really likes to describe me as, fundamentally, a storyteller. Having someone else name the thing—like autobiography—made me examine how prevalent it truly is within my work. Almost all of my video works are video essays wherein someone is voicing a story or narrative. Even in my two-dimensional and installation work, narrative feels very resonant.

My particular method of storytelling is visual art, which, again, offers me experimentation in the telling and form. Sitting with stories that have been lost, forgotten, or intentionally disappeared is really where I’ve been invested with narrative. When it involves the personal, such as work around the Samaritan Foundation, I like being able to start from a point within my own life and then expand, pivot, or twist from there. Earlier on in my practice, I was invested in thinking through things like the slant, tangent, divergence, lean—and how these terms might be queer in and of themselves, or offer a path towards queerness and difference. I think that still remains in my practice, and perhaps feeds that drive for deviating narratives.

Networks of (Be)longing at Center for Contemporary Art & Culture, installation view, Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, OR, 2020 [photo: Mario Gallucci; © 2020 Rami George, courtesy of the artist]

List Projects 21: Rami George at MIT List Visual Arts Center, installation view, Cambridge, MA, 2020 [photo: Peter Harris Studio; © 2020 Rami George, courtesy of the artist]

LM: That also might relate to the way that assemblage works in your collages, such as those that you featured in your List exhibition, as well as your large-scale billboard sculpture Untitled (mapping) (2020) at Paragon Arts Gallery. There’s a different type of logic—or maybe a better word is relationship—in how you group visual information, like the dowsing diagrams, or processes for divination, with the photographs of your mother’s ceramics. How did you select these sources, and how do you view them interrelating?

RG: With my collage work, grouping usually starts through experimentation and play. It’s that classic studio thing where you make a pairing or an overlay—perhaps late at night, maybe with a little tequila—and you wake up the next morning and notice something you didn’t initially see or intend, but it feels resonant. I still find this process very valuable and something I want to keep in balance to the research.

For the collages present at the List, I was thinking through how to include some of the primary source materials of the Samaritans. They published a lot of content, most of which is not for me—in terms of language, concepts, homo- and transphobia—but there are also some really beautiful moments, particularly visually. In speaking with my mother, I learned that many of these illustrations were visualized by Linda Greene, the head of the community, but translated to the page by more artistic members of the community, such as Allen Ross (an experimental filmmaker involved in the group, who later went missing, and was ultimately discovered murdered) and my mother.

I then mixed these materials with select family photographs. I’ve used familial photos quite a bit throughout my work, but in this case I was particularly interested in finding and using the stranger images—people turned away from the camera or hidden in the shadows, domestic spaces and objects, et cetera. I was thinking how the content in the collages was part of my upbringing, voluntary or not, so these teachings and illustrations can sit next to these moments of domesticity and family, and they start to spill and overlap upon each other.

With the opportunity to exhibit at Paragon, specifically activating their windows, I was thinking through a billboard structure. It’s not immediately visible, but the placement of the materials roughly corresponds to the layout of the US. I wanted to intuitively map or trace my own family’s movements across the US, as related to our proximity and interactions with these varying intentional communities. A lot of the materials are actually present elsewhere, such as collages at the List, or within Untitled (with my father)—this is another part of my practice, using and reusing imagery to tell slightly varying narratives. To connect all these materials, I used part of an illustration produced by the Samaritans as the interweaving mapping. Initially I was imagining this work like a flow chart, but I decided that a nonlinear mapping actually made more sense for the work. As often happens, I was pleasantly surprised at many moments of connection—spirals landing roughly in Portland, the central points of the illustration in Guthrie with the Samaritan Foundation’s brief headquarters, et cetera.

LM: Keeping with these ideas of layers and assemblage, they seem to seep into the digital realm of your video playlist. Do you see the playlist as documentation of the works concerning the Samaritan Foundation, or as a work in itself, or perhaps as a kind of footnoting process?

RG: I initially made this video playlist as part of a public program at the List and … screened it at the CCAC this past fall. I was thinking through all of the public media content that already exists around the Samaritan Foundation—a documentary called Missing Allen, [which was] a Dateline special, a ghost-hunting episode about the jail we briefly lived in, a made-for-TV docudrama, footage of Linda Greene explaining dowsing. I also wanted to find a place to include some of Allen Ross’s filmic work. So, the video playlist is composed of many snippets from these sources, as well as a few of my own videos created in relation to the community. I also included an early video essay made before I really dug into the Samaritan story that, in retrospect, I can see is so deeply connected. Like other parts of my practice, I wanted all of these fragments to sit next to each other, to act as context, or footnotes, or even another essay or collage. I think it functions both to catch people up to the story, but it also does something like a stutter or a reiteration—saying the same, or a similar, thing, with slight variation. Perhaps it goes without saying that the ways in which the Ghost Adventures episode chooses to tell this story are vastly different from the ways that I choose to in my own practice. I really appreciated letting them sit next to each other, though.

LM: There really is so much context around the work—it’s staggering. Every time we talk, you mention something new.

RG: There is! And I think that’s why I, and others, have been so interested in the story. It’s salacious, it has all the makings of a TV drama—and there is one. But then it also has all of these strange coincidences and connections, micro and macro, and that’s what I’ve been interested in sitting with.

LM: That also leads us to the affects, or emotions, that are so present in the works and research. What was the emotional process like for you in engaging with the recollected conversations, texts, and visual ephemera for works such as Untitled (with my father) and Untitled (the ashram)?

RG: I’ve been interested in steering my work towards emotions, the physical, the body, in addition to the mind. There was a point where I was really invested in theory, and then I decided it wasn’t exactly where I wanted to situate myself. So, sitting inside of my feelings and lived experiences helped me get out of the theory and into something like affect or emotions.

In terms of the research, there are times when it’s easy, pleasurable, weird, or interesting, and then there are times where it gets very difficult and painful. I have these letters between my parents that have intense anger, sadness, and animosity because they were going through a custody battle and a divorce—and they were adults, and my sister and I were children, so of course we experienced this time in different ways. There’s a letter that appears in Untitled (with my father) that describes how my sister would say beautiful prayers for my mother, but how I wasn’t into praying so much. It resonates with our life experiences—she found religion, and I was always skeptical. Parsing through it, it could be from this traumatic experience directly related to my mother’s search for spirituality, or it could be a part of me that’s always been more observant and skeptical.

The presentation can also hit these emotional points. Sometimes I’ll make the work and feel ready to show it, and when I finally experience it live, projected and amplified, suddenly the emotions really hit. Ultimately I want to honor and invest in those experiences, though. I’ve been thinking a lot about radical honesty—what it could mean, particularly in our world right now. I hope to tap into the painful moments, in addition to the beautiful and pleasurable ones.

With Untitled (the ashram), I was surprised at my father’s hesitation to speak about the ashram. With a little time, I can understand it more. Of course, it’s easier to talk about a community that no longer exists—like the Samaritan Foundation—but there’s a different sort of ethics or responsibility in speaking towards a community that is still very much continuing. I wanted to acknowledge and respect that trepidation in the work.

Rami George, Untitled (mapping), 2020, inkjet print, wood, 84 x 96 x 28 inches [photo: Mario Gallucci; © 2020 Rami George, image courtesy of the artist]

LM: The way you describe investing in emotion seems so pertinent to this work, since it’s been a continued journey. It’s a series, but made over a long expanse of time—so the idea of investment honors that time. It’s also generous that you invite people in to share in that emotion with you.

RG: I’ve had some very meaningful interactions with people who have viewed the works, and perhaps shared tangential experiences, like a custody battle, or losing a parent, or another big rupture. Someone told me about their parent having been murdered and there being a Dateline episode about it—so, these instances in which your private life becomes public, which is very much a part of this work for me. I want to share my story with all of its weirdness. I’ve seen it resonate with other shared experiences, as we all have our own traumas, losses, and grief.

LM: An aspect of the work in its presentation at the List that makes the emotion palpable for me—and I did not see it in person because of COVID-19, but you can sense it in the installation photos—is the built environment. You constructed an architectural form for the works at the List that mirrored the Seminar Room in the Samaritan Foundation’s site in Oklahoma. You also built out a dual screen in the presentation of Untitled (with my father) and Untitled (the ashram) at the CCAC. Did this spatial research differ from the processes you’ve already mentioned?

RG: That also started out as an intuitive or an aesthetic drive. At the List, I wanted the first thing that you would encounter to be the back of a wall. I wasn’t exactly sure why, but I liked the idea of initially offering the viewer something unexpected, and maybe not initially legible as art—like a jolt, or a stall, as you enter.

So, I had this drive to have these walls present in the space, [though] I still wasn’t exactly sure why or what for. But as I kept working on other components of the exhibition, I remembered that years prior, Kelly Raines—an amateur historian, in Oklahoma, exploring the Samaritan Foundation—had sent me a bunch of material, including a floor plan of “The Monastery,” which is what the community called the converted jail in Guthrie, Oklahoma, that we were living in. When I looked at the floor plan, I noticed a room named the “Seminar Room,” and I realized that the shape of that room could be translated to the List, and suddenly all the pieces clicked into place. First, to have this confrontation with nonart and that disruption of expectation; and second, it being related to a site used for dowsing and teachings of the community. Then I was thinking through what it means to have my work, which includes these dowsing charts and instructions, inside a mock seminar room. I also started to lean into the idea of a room within a room, and what that might mean or convey. There’s an intimacy, and I think a relation to an interior, or psychic, space. We did end up making a label for the space, naming it Untitled (After the Seminar Room), so the reference is there, but again, only if and when you choose to dig deeper.

LM: I think your idea about complicating intentional communities is really prescient. Not to politicize your work in a way that it doesn’t intend, but just thinking about multiplicity and nuance is so important in this extremely divisive moment in history, because thinking in binaries seems to stall the real work.

RG: I hope to live in a world full of nuance and care and support. Another term that I keep thinking about, and finding in my work, is community. I feel like we are really grappling with that term in this moment: What does a local community look like and need, what does a global community look like and need? I appreciate that you relate the work to this current moment. I don’t think I’ve included those references so explicitly yet, but I am seeing that ongoing question of community and belonging as being this connecting thread, of the then of my own history, to the now.

LM: We can’t cover all of the complexities of this year and how they might have affected your research, but I did want to ask you what is your approach when you face obstacles?

RG: I was very excited about the prospect of being in residence in Portland, and flying out to create Untitled (the ashram) in person, but, as we know, the world has a different idea for all of us in this moment—and I’ve been trying to listen to that, too. I have often created work from a distance, so the shift to a remote project was not so difficult. I was able to pull from different strategies that I’ve used in the past—requesting footage, working with Google Maps, incorporating close scans—and for the first time combining them into a single work. Although COVID-19 is only mentioned once in passing in the work—it’s named briefly in an email correspondence requesting footage—I do feel like this work is very much a pandemic film. Even the use of a phone call feels resonant to that—something my father and I have been doing a lot more of this past year. Luckily, I have some great friends and peers (including you, Laurel) who have been willing to help me along the way: shooting footage when I can’t physically get somewhere, scanning dictionary definitions for me, et cetera.

LM: Thank you, Rami. Lastly, may I ask, where do you see this work leading next?

RG: With this deeply personal work, I often need to take some rest and breaks. That being said, I’m currently finishing up a couple of projects related to this content. While I was working towards my List exhibition, I was simultaneously collaborating with a close musician friend of mine, Joel Midden. I asked Joel to help respond to the Samaritan’s primary publication, Virtues, Laws & Powers. In this book, there are 31 abstract line drawings that respond to “virtues” of the world. I find these drawings really strange and magnetic, and was curious what it would look like to respond to them sonically. Although it didn’t end up fitting into the exhibition, Joel and I have continued collaborating, and have now finished an EP of the first 10 sonic responses. Later, I asked a designer friend of mine, Joshua Hauth, to help me polish up some ideas for a limited-run poster to coincide with the release of this EP. Some early visual treatments by Joshua ended up opening some doors to think about what a video treatment could be, particularly through 3-D animation. Through yet another friend, I was connected to an incredible animator in Chicago, Mak Hepler-Gonzalez, who I’ve now been working with to translate this EP into animation. These remote collaborations have been really exciting to me in this time of both confinement and unlimited virtual possibilities.

Rami George is an interdisciplinary artist living and working in Philadelphia (Lenni-Lenape ancestral lands). Their work has been presented in exhibitions and screenings at MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge; Anthology Film Archives, New York; Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow; Grand Union, Birmingham; the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London; the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; LUX, London; the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; and elsewhere. George received a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an MFA from the University of Pennsylvania. They continue to be influenced and motivated by political struggles and fractured narratives.

Laurel V. McLaughlin is a writer, curator, and art historian from Philadelphia, based in Portland, OR (on the unceded lands of Bands of Chinook and Clackamas, Cowlitz, Kathlamet, Molalla, Multnomah, Tualatin Kalapuya, and Wasco peoples). She uses the V in her name to honor her maternal grandmother, Vera. McLaughlin is currently a 2020–2021 Luce/ACLS Dissertation Fellow in American Art and a history of art PhD candidate at Bryn Mawr College, writing a dissertation concerning migratory aesthetics in performance art situated in the United States, 1970s–2018. Her criticism, essays, and interviews have been published in ART PAPERS, Art Practical, Performa Magazine, Contact Quarterly, Performance Research, and Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture, and she has organized exhibitions and programming at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, FJORD Gallery, the University of Pennsylvania Incubation Series in collaboration with the Arthur Ross Gallery and the ICA Philadelphia, AUTOMAT Gallery, Vox Populi, the Center for Contemporary Art & Culture, and Paragon Arts Gallery, among others.