Rallou Panagiotou, Tranquil and Unbroken (Sphinx Gold), 2015, aluminum, Peugeot car paint

[courtesy of the artist, Ibid London/Los Angeles, and Radio Athénes, Athens]

Rallou Panagiotou

Share:

Greek artist Rallou Panagiotou has a busy few months ahead: she is participating in an exhibition at Tate Britain that opens in November 2015 as part of Art Now; a show curated by Andreas Angelidakis, Vittorio Pizzigoni, and Valter Scelsi at PAC-Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea titled Super Superstudio [October 10, 2015–January 6, 2016]; and a group exhibition presented by Glasgow Sculpture Studios and curated by Louise Briggs, with new commissions by Eva Berendes, Stephanie Mann, Vanessa Safavi, and Samara Scott [January 23–March 5, 2016]. Presented here is an early career survey of Panagiotou’s oeuvre to date—beginning in 2008 and ending in 2015, when she presented a new work on the island of Mykonos, Greece, as part of a project by Dio Horia.

Rallou Panagiotou, Common Deity (Pink Lycra), 2014, print on archival paper, 108 x 79 cm [courtesy of the artist, Ibid London/Los Angeles, and Radio Athénes, Athens]

Rallou Panagiotou, Perfecto, 2014, print on archival paper, 108 x 79 cm [courtesy of the artist, Ibid London/Los Angeles, and Radio Athénes, Athens]

Panagiotou has said that her practice is about building “stages,” and it is precisely in stages that her work has evolved. In 2009, just one year after graduating from the MFA course at the Glasgow School of Art, Panagiotou was nominated for her home country’s DESTE Prize—Greece’s answer to England’s prestigious Turner Prize. For the nominee show, she produced an impressive sculpture, Darklands (2009), which consisted of an elegant yellow stage resting on two large black blocks—a base inspired by architect Lina Bo Bardi. On the platform, two figures cast in black Jesmonite were arranged in a kind of Don Quixote-Sancho Panza relation, one large and graceful, the other short and round. It was a bold and precise introduction to Panagiotou’s compositional logic: what she describes as “a synthetic topology,” in which an “object is contained by its surrounding architectural forms.” Panagiotou notes the work was really about finding a way to bridge the two cities she divides her time between: Athens and Glasgow.

One year later, Panagiotou put together an exhibition at Gallery AMP, Athens; titled Supernature: An Exercise in Loads, it featured the works of some 20 artists, including Markus Amm and Jennifer West. It was the realization of a dream Panagiotou had while growing up in Kypseli, a densely populated urban neighborhood at the heart of Athens, where a bodybuilding gym owned by a man named Spyros Bournazos fascinated her. The show considered the gym as a hybrid form: a space of bodily transformation and formal intensity. It drew from her experiences of Athens in the 1980s and considered the nationalism inherent to Greek bodybuilding with respect to the international bodybuilding community. At the same time, the show was about the embodiment and shaping of form, and how that might translate to the practice of an artist. For the show, Panagiotou produced a triangulation: artworks from the Viennese actionists, contemporary Scottish painters, and others were hung in the bodybuilding gym, where Panagiotou filmed the scene as men worked out. Then she presented the footage in the gallery space. On the opening night, bodybuilders performed in the gallery in front of Robert Longo’s Bodyhammer: Beretta (2008), a hyper-real charcoal drawing of a gun.

Rallou Panagiotou, Eyeliner (dramatic), 2013, black marble, inkjet print on leatherette, wood, iron, spray paint, bronze tubes, 45 x 88 x 30 centimeters [courtesy of the artist, Ibid. London/Los Angeles, and Radio Athénes, Athens]

Panagiotou held her first solo show in 2010, also at AMP. Titled Heavy Make Up, it was a confident exhibition of large-scale abstract sculptures consistent with the architectural sensibility displayed in the preceding years. These works were produced from materials including metal, wood, Plexiglas, and Jesmonite, and followed a color scheme of red and black, in reference to ancient Greek pottery painting. In Athenee (2010), black cuboid frames made out of scaffolding supported a plinth for a red Jesmonite bust of Athena—barely recognizable save for the suggestion of a helmet and a familiar profile—and a pair of blue jeans encased between panes of red Plexiglas.

Historical references ran thick: in Great Nostalgie (2010), a composition of scaffolding, lacquered wood, and synthetic leather essentially looks like the abstract articulation of a constructivist sketch for both a diving board and a dive. The composition created a chain reaction of subjective references: Hockney’s swimming pool, the constructivist set designs of Popova, Yves Klein’s Leap Into the Void (1960). Meanwhile, denim canvases printed with bleach through the batik process featured abstract forms taken from photographs that Panagiotou’s civil engineer grandfather took of the bridges he designed and constructed; these works recalled Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. Great Nostalgie communicated at once the burden of formal histories and the potential of release embedded within them. At the core of its sentiment—the leap—is the gesture.

Among the works exhibited in Heavy Make Up, one in particular stood out: Your Voice, My Earring (2010), a white marble form of an ear hanging on the wall and wearing a round earring made of lacquered yellow wood, with a hook rendered in sharp metal. The earring was different from the sculptures on the floor for a number of reasons, not least in that it deviated from the color palette of the larger works. As recognizable in art as it is in life, this common accessory, rendered with minimalist compositional flair, offered an accessible point of entry into the formal questions laid out in Panagiotou’s “architectural milieus,” in which high and low culture exist in a kind of horizontal inversion. The earring articulated the concept behind the exhibition’s title—which Panagiotou told me is about “appropriation/decor as the most essential form of artificiality”—and locating our historical relationship to spectacles of display most clearly in, and on, the body itself.

Rallou Panagiotou, Your Voice, My Earring, 2010, marble, metal, lacquered wood [courtesy of the artist, Ibid. London/Los Angeles, and Radio Athénes, Athens]

The earring articulated the concept behind the exhibition’s title . . . and locating our historical relationship to spectacles of display most clearly in, and on, the body itself.

There always seems to be a work that doesn’t quite fit within a Rallou Panagiotou exhibition—a break in the chain that prevents the closing of the circle. It is this touch that makes her stance distinctly anti-modern: there is always a loophole into the heart of her conceptual web, and beyond it. Take Panagiotou’s exhibition with London’s Ibid. Projects in 2011 as part of ReMap KM’s satellite programming for the Third Athens Biennale. Titled Artists and Engineers, it was an immaculate presentation of an entirely new body of work made that year, and a thrilling development that presented a noticeable shift in the artist’s practice. Although her formal sensibility remained, gone were the uniform reds and blacks of the previous series, for instance. Works were lighter, too, both in their rendering and in their referencing: here, Panagiotou’s visual lexicon drew more from pop culture than art history. In Strong Scent (2011), metal rods protrude upward on one side of a hot-pink stand with three legs, designed after a bridge built by the artist’s engineer grandfather, while a large, black, slumping Jesmonite form of an oversized Chanel No. 5 bottle stands on the other side. The pink stand is placed over a plank of wood, printed with the pattern of tangled cassette tape, upon which a bronze cast of the same Chanel bottle lies on its back. In Cleopatra Mild Beauty (2011), a black Jesmonite abstraction of an Egyptian figure kneels on a plinth covered in standard white bathroom tiles. (The artist is obsessed with tiles; she prints on them, too.) The image of a shampoo bottle is printed on a table that cuts into the plinth’s side.

The anomalous sculpture in Artists and Engineers was a hand-carved gray marble drinking straw, presented on the floor. The suggestion of a cup was articulated in a metal sphere on the ground behind it, and by two blue metal sheets alongside it that curve upward and out, Caro-esque. She showed three straws—green, white, and black—at the concurrent Athens Biennale, MONODROME, where they were perfectly installed on the chipped marble floor of the old Diplareios Art and Design School in the city center. These works were my first experiences of Panagiotou’s ongoing Liquid Degrade series: marble straws that exemplify a deft, rigorous, and intellectual relationship to material and form that is at once sincere and irreverent.

Panagiotou once told me that one of her favorite television scenes of all time is in Spongebob Squarepants, when Spongebob goes ape for marble—he wants to feel it, lick it, taste it, become it. This material fetish is epitomized in Liquid Degrade and another series, Eyeliner, in which the thick line denoting an application of eyeliner in instructional beauty graphics is replicated in marble, and accentuated with metal details—often, fluorescent colors added in aluminum, like sunrises emerging out of marble streaks. Both series communicate what Panagiotou has described as a “corrupted modernism.” This gothic dream permeates two sculptures presented at Galleri Riis in Oslo in 2014, in an exhibition called Liquid Degrade. The first is The Deconstruction of Leisure (2013): a white marble straw emerges out of a wooden shelf covered in leatherette, printed with the image of colored liquid gradiating from a deep violet to a rich, pastel tangerine, like the sky of a tropical sunset. Delicate brass curves are held aloft by bronze and zinc fittings; they swirl around the straw offering another level of movement beyond the impressionable tones that color the shelf’s skin. Eyeliner (dramatic) (2013) works in similar fashion: the black marble shape of the eyeliner’s mark is accentuated by wisps of fluorescent orange aluminum, and held up by two bronze tubes that emerge out of another shelf covered in leatherette, this time printed with the image of white bathroom tiles.

Rallou Panagiotou, Fabrics and Milieus, 2015, print on marble, aluminum cast [courtesy of the artist, Ibid London/Los Angeles, and Radio Athénes, Athens]

This is modernism in the club, or history with a hangover, at once elevated and pulled down. Both sculptures encapsulate an experience of contemporary culture on a sensory rather than affective level. The straw is the signifier that ignites the memory of a personal experience: they echo the bubbles that burst on your tongue when you sip soda, or the phantom feeling of the cold cup in your hand. The eyeliner is the memory of the toilets in the dark black cube of a discotheque, illuminated by flashing strobes and glasses glimmering atop a sweaty bar. These are not only the relics of the present or the detritus of mass consumption. They are feedback from a feeling in space and time. Think of a classic Coca-Cola ad, in which a crisp sizzling when the can opens tells us: “It’s the real thing.”

The odd sculpture out in the Oslo show was Off Shore (2013): a pair of diving fins constructed from rubber and metal, pinned to a rectangular iron board covered in white leatherette. A series of stripes move from orange to sky blue over the leatherette, from top to bottom, a pattern taken from an abandoned boat that Panagiotou photographed because she liked its paint job. Like the earring in 2010, the fins were the most recognizable objects in this particular constellation of abstractions—a signpost on the road to something that has not yet fully come into being.

Off Shore connected with Panagiotou’s second solo exhibition in Athens, which opened that same year at Andreas Melas & Helena Papadopoulos. Second Plateau was another show that coherently illustrated a practice, and its ceaseless evolution. By 2014 Panagiotou’s sculptures had become small, compact, concise. The tall, slim, towering arcs of Eyes Like a Geyser (2010), in which an eye is rendered within a black and menacing frame suggestive of a dark ancient temple, resonated in the now small, black marble arches of Goth Gossip (2013). These arches stand on a base covered with an inkjet print on leatherette (a scan of a faux emerald earring), alongside small, black spheres. The work at once exudes the off-center calm of a De Chirico landscape and the directness of a brand logo. Signage is very much a part of Panagiotou’s practice, she tells me.

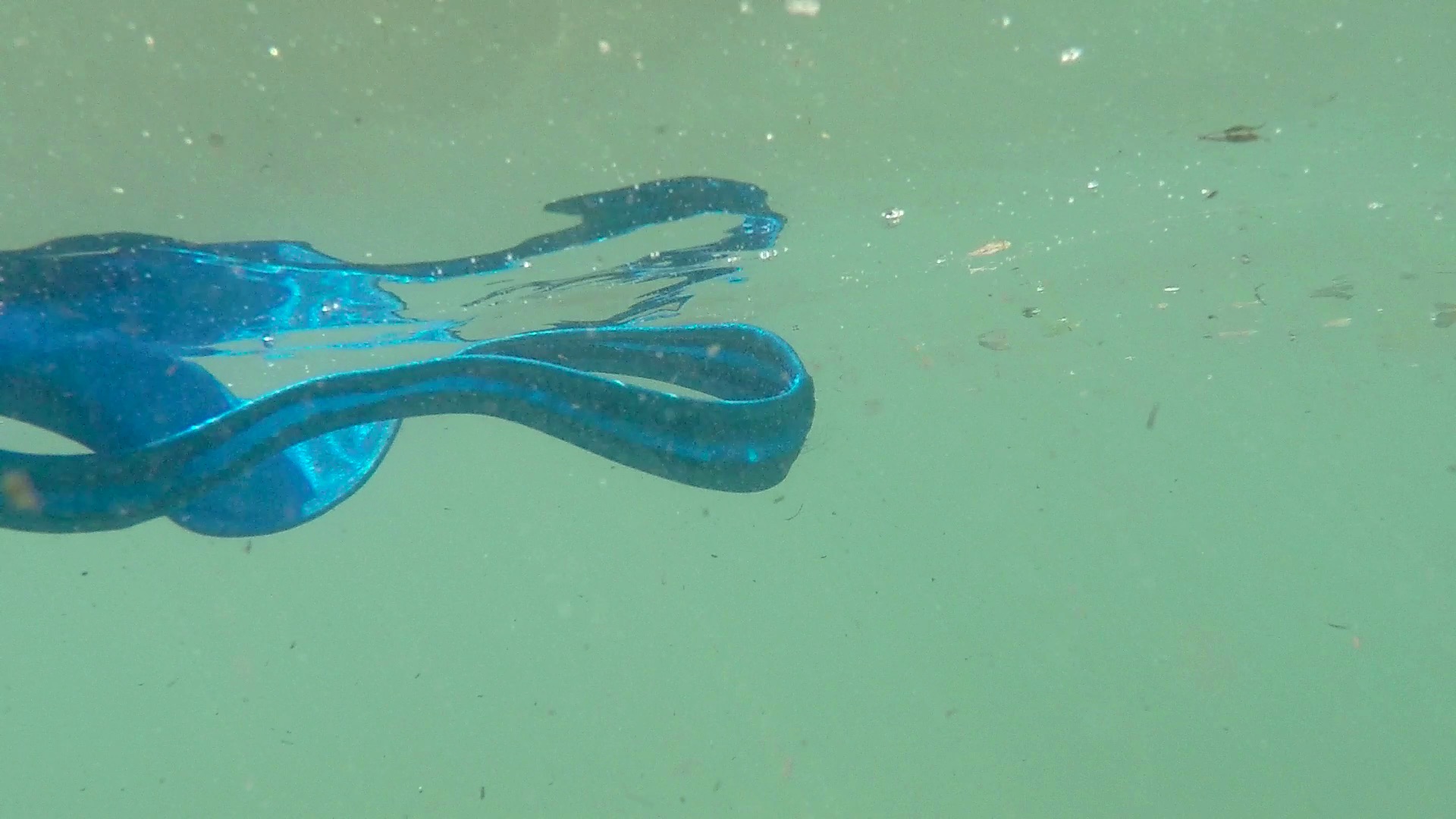

Rallou Panagiotou, film stills from Calypso, 2015 [courtesy of the artist, Ibid London/Los Angeles, and Radio Athénes, Athens]

Second Plateau was a postmodern road trip—the topology of a place the artist describes in a paragraph-long story about the path to the exhibition’s title. The text reads like the synopsis to a Lynchian B-movie, in which the road is as much an ideological space as the plateau itself. Things the artist describes in writing become form in the gallery. Fig trees feature, appropriately, in The Proper Way to Eat a Fig (2013), named after a poem by D.H. Lawrence. The sculpture is a broken wire fence constructed out of iron, held vertically on a low leatherette-covered wooden plinth, printed with an image of cement. Figs cast in bronze are suspended from the base. As a whole, the show was the visualization of a memory through a fragmented landscape, mapped out with objects standing for data points, in what feels like a journey mapped out in riddles.

Among the works in Second Plateau was Rubber Lineage (2013), more oversized diving fins constructed from layers of rubber, metal, and a slab of beautifully polished black marble, cut to fit the shape of the fin’s expanded tip. This work seems to confirm what Off Shore suggested: Panagiotou’s journey holds the sea in full view. Her destination is mapped out further in Layer on Relational Classifications (2013), in which rectangular leatherette-covered planks of wood printed with an image of sand at night (from a very specific beach, according to Panagiotou) are positioned on the floor, over which an aluminum cast of a beach mat hovers. Layer on Relational Classifications is composed as a series of waves; it catches movement in a carefully constructed abstract space. Its title is at once an admission and a challenge: it both invites and counters our tendency to locate meaning through and beyond familiar systems of reference.

In this framework, there is a methodological relationship between Panagiotou’s oeuvre and that of Hong Kong artist Lee Kit, who takes every aspect of pop culture as a readymade—from a lyric of a song, to people’s tendency (in Hong Kong, at least) to drown their sorrows while singing karaoke in bars. This readymade domino effect works virally: by its definition, even the karaoke bar is a readymade, as is everything else contained within it, the behaviors and emotional expressions of its patrons included. Panagiotou operates a similar filter, processing visual codes through the formal language of representation in order to consider our personal relationships with the material world.

In Plato’s famous dialogue, Phaedrus, set on the outskirts of Athens, Socrates admits to his interlocutor that sometimes, when he speaks, he doesn’t know where the words are coming from. It is as if they are being poured into him, he says, as though he were some kind of vessel. Here, Plato suggests not only that he effectively controls the mouth of his mentor in these recorded dialogues, but that he considers expression itself as a flow of found or inherited words and histories. With Panagiotou, as with Kit, every “thing” relates to such a system of ready- made associations; words and objects become forms through which both personal and collective narratives are projected and associated.

Kit has said that his interest in printing the logos of such products as Nivea Creme onto cardboard “canvases” relates to the emotional relationship we have to them. For Panagiotou, however, the representation of one material through another is something that “stands for mediation of the actual experience; the neutralization of sentiment, of affect.” The trick is the cognitive dissonance such material and formal inversions induce. In Shampoo (2012), for example, she presents the same bottle she used in Cleopatra Mild Beauty, this time as a marble outline encased within a wooden frame covered in leatherette printed with an image of swimsuit Lycra. In this neutralization, the commodity itself—its identity and the critique of it—becomes so much a part of the work that its existence is abstracted, even negated.

Rallou Panagiotuo, Installation view: Heavy Make Up, 2010 [courtesy of the artist]

This sensibility is Warholian: everything is potentially iconic, from a soup can to a body, depending on how the thing is framed. When Panagiotou talks about finding the right image of cement for Second Plateau, for example, she says that it had to be “archetypal”—like finding the Gene Kornman among Marilyn shots. Taken as literal assemblages of archetypal commonalities, Panagiotou’s sculptures turn objects such as blue jeans into signifiers of things as “micro” as sensations, recollections; and aesthetic preferences into such macro concerns as class, labor, production, and consumption.

The shampoo bottle appears again in Panagiotou’s latest project, Lycra Proper, presented by Dio Horia, a new exhibition platform launched in summer 2015 on the Greek island of Mykonos. Cleopatra Shampoo (Blue Streak & Flash Gold) is the outline of a bottle that was originally made in marble, cast in aluminum and painted in the Prussian blue and golden yellow tones of the original work. These outlines are placed as a standing sculpture on an Ikea “Eric” drawer—essentially, an office cabinet, symbolic of the bureaucratic division of time between leisure and work. It is surrounded by aluminum casts of swimsuits painted with car enamel; other works, also standing on drawer-plinths, even state what manufacturer the paint is from (Fiat, for instance, or Land Rover). Positioned on the floor near these works is Tranquil & Unbroken (Sphinx Gold) (2015): a small, unassuming aluminum cast of a beach sandal, one strap broken, painted with a shiny, Lycra-esque finish in rose gold—the industry of leisure distilled to a mass-produced flip-flop like a new latrine, or Buddha, for the 21st century. To borrow Panagiotou’s phrase, this is “modernism on the beach.” Coming full circle to the diving board of Great Nostalgie in 2010, we have reached the water’s edge—and the only way forward is liquid ground.

This ground is mapped out in Lycra Proper through Fabrics & Milieus (2015). This series consists of marble slabs hung on the wall, each printed with the image of a Lycra swimsuit and paired with an aluminum cactus. The cacti were cast directly from live plants, as opposed to being cast from sculpture, with is normally the case. Yet the title is what distinguishes this work most of all: it succinctly describes the systems of composition she developed and referred to so visibly in 2009, and which have, year by year, become more encoded into each object’s making. According to Panagiotou, Lycra Proper is based on the perception of “Lycra as an idea rather than a material”—on an expansive web of meaning, a plateau, or a sea filled with material histories. Thus, Lycra the material becomes Lycra the milieu—one in which a reassessment of the past might take place so that we might consider the future as the organized experience of such a reappraisal. In Panagiotou’s world, the materials for the future are present in what has already been left behind: all it takes is a point of departure.

Stephanie Bailey is an ART PAPERS contributing editor.