Paul Ramírez Jonas: Disappearing Vows, Disguised Lies

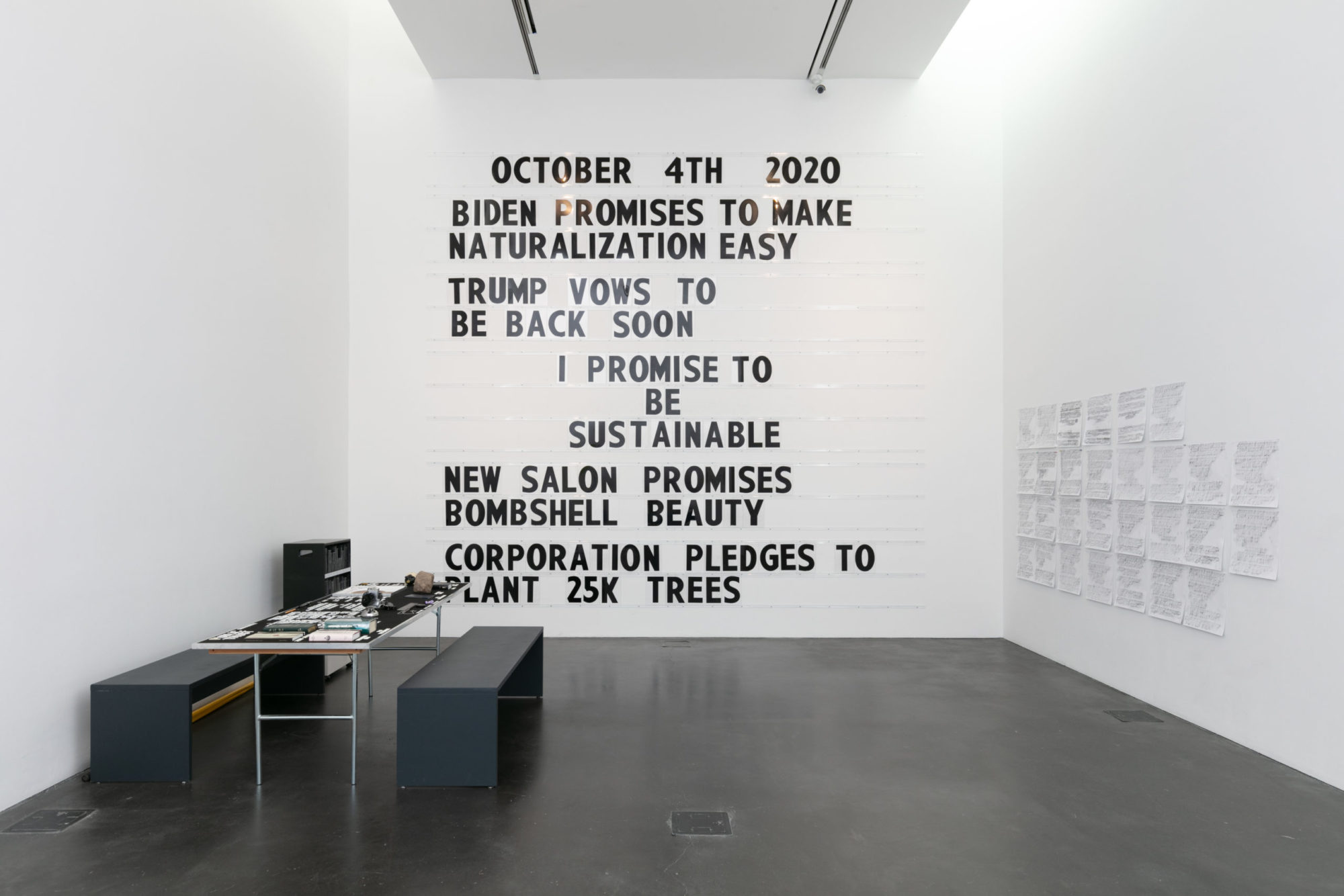

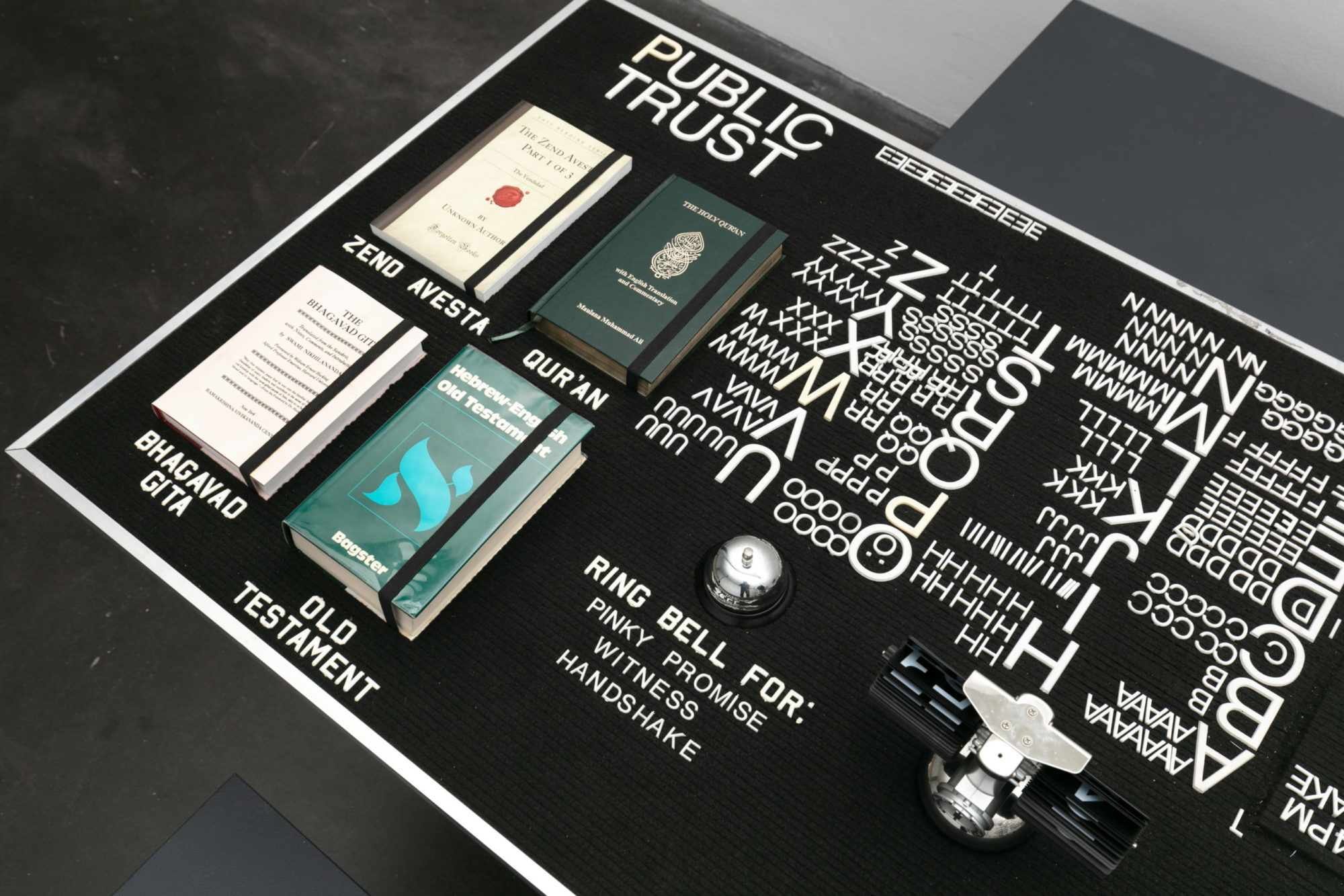

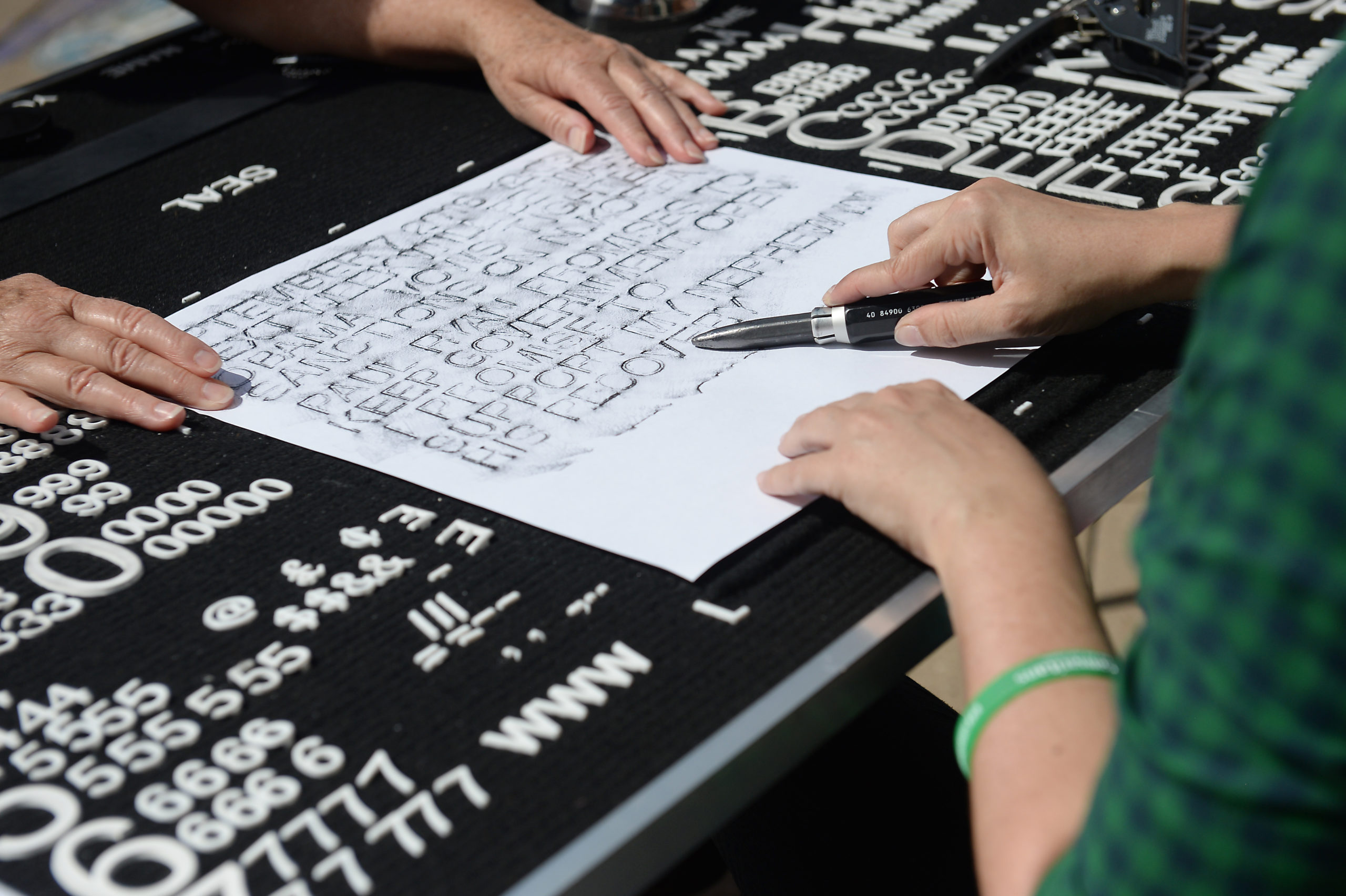

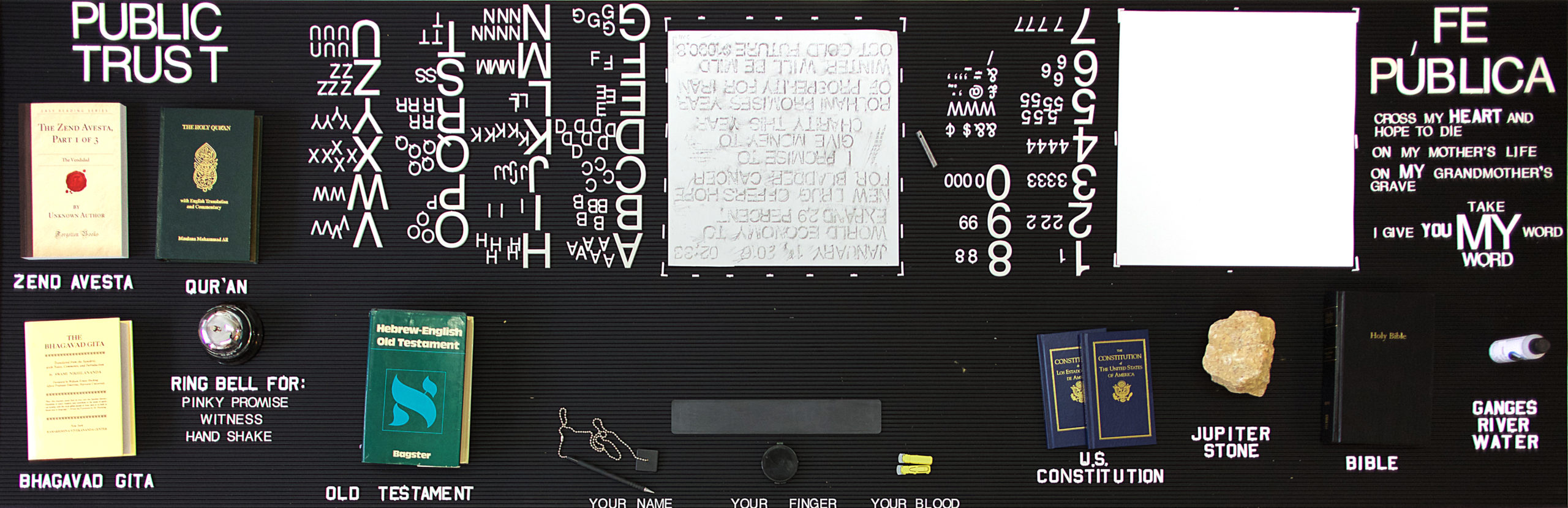

Paul Ramírez Jonas, Public Trust, 2016, table (birch plywood, felt, plastic letters, elastic, Bible, Bhagavad Gita, Hebrew–English Old Testament, Quran, Constitution of the United States, Constitution of the United States in Spanish, Zend Avesta, plastic bottle with Ganges River water, Jupiter Stone, disposable medical lancets, piggy bank, call bell, ink pad, pen and ball chain, flip clock, embossing seal, paper, and graphite) and marquee (plastic letters, plastic rail, letter-changing pole, cabinet, and hardware), dimensions variable, produced in Boston by Now + There [courtesy of the artist and Galeria Nara Roesler, and MCA Denver]

Share:

A variety of sacred and civic texts, an alphabet of letter blocks, a folding table, and a 16-foot marquee provide the framework onto which the public can provide a promise. “What is interesting about promises is they become a truth or lie,” Paul Ramírez Jonas told me in an interview about his artwork Public Trust, which is currently on view at Museum of Contemporary Art Denver.

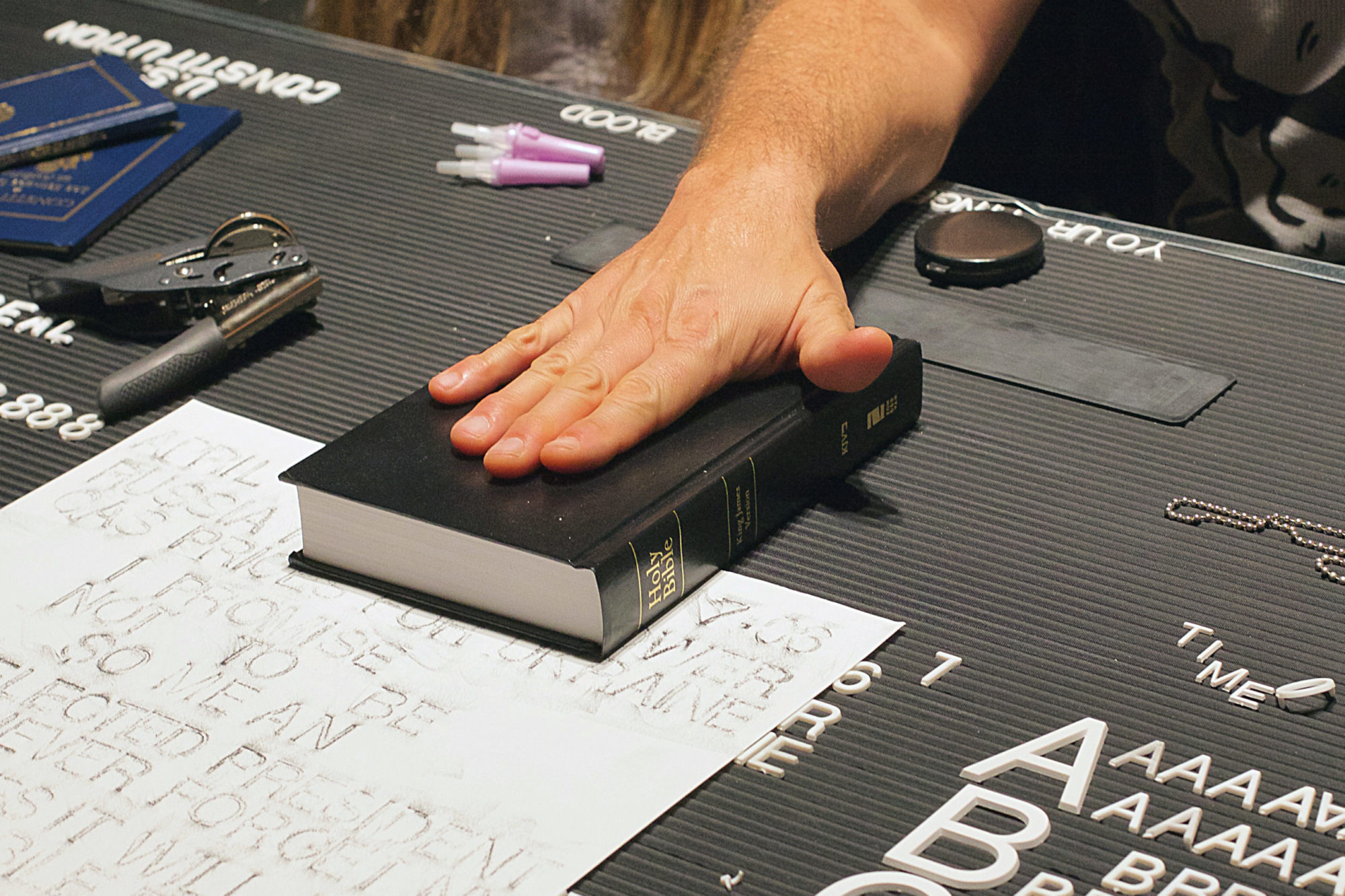

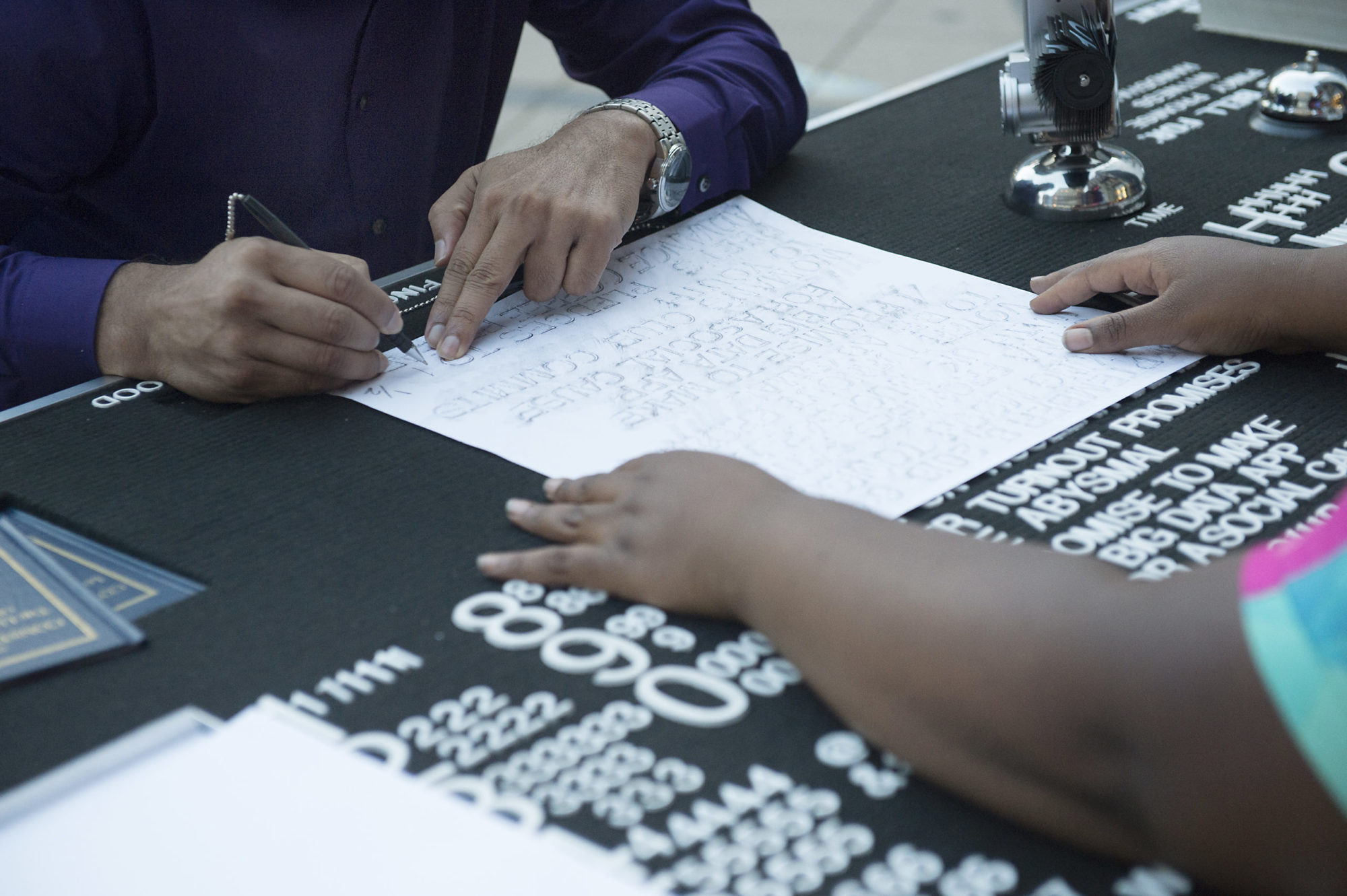

Speaking makes one’s intentions audible. Some speech acts are formal commitments, such as marital vows or pledges of allegiance; many such utterances are casual, like “See you tomorrow,” and some are duplicitous. In Ramírez Jonas’ participatory artwork, visitors make a promise, then witness it documented, duplicated, notarized, and enlarged for public consumption to test our assumptions about the power of promissory language.

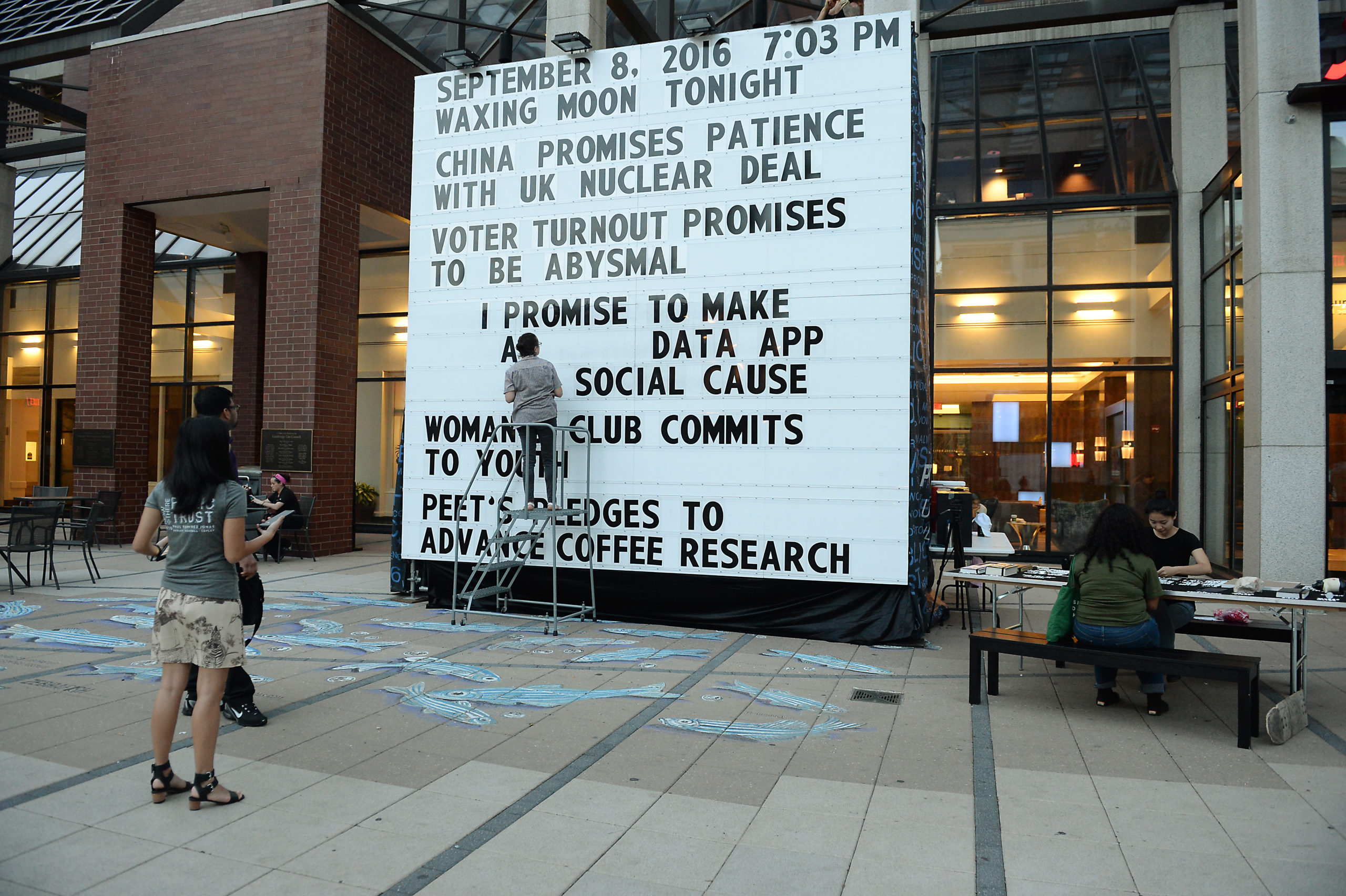

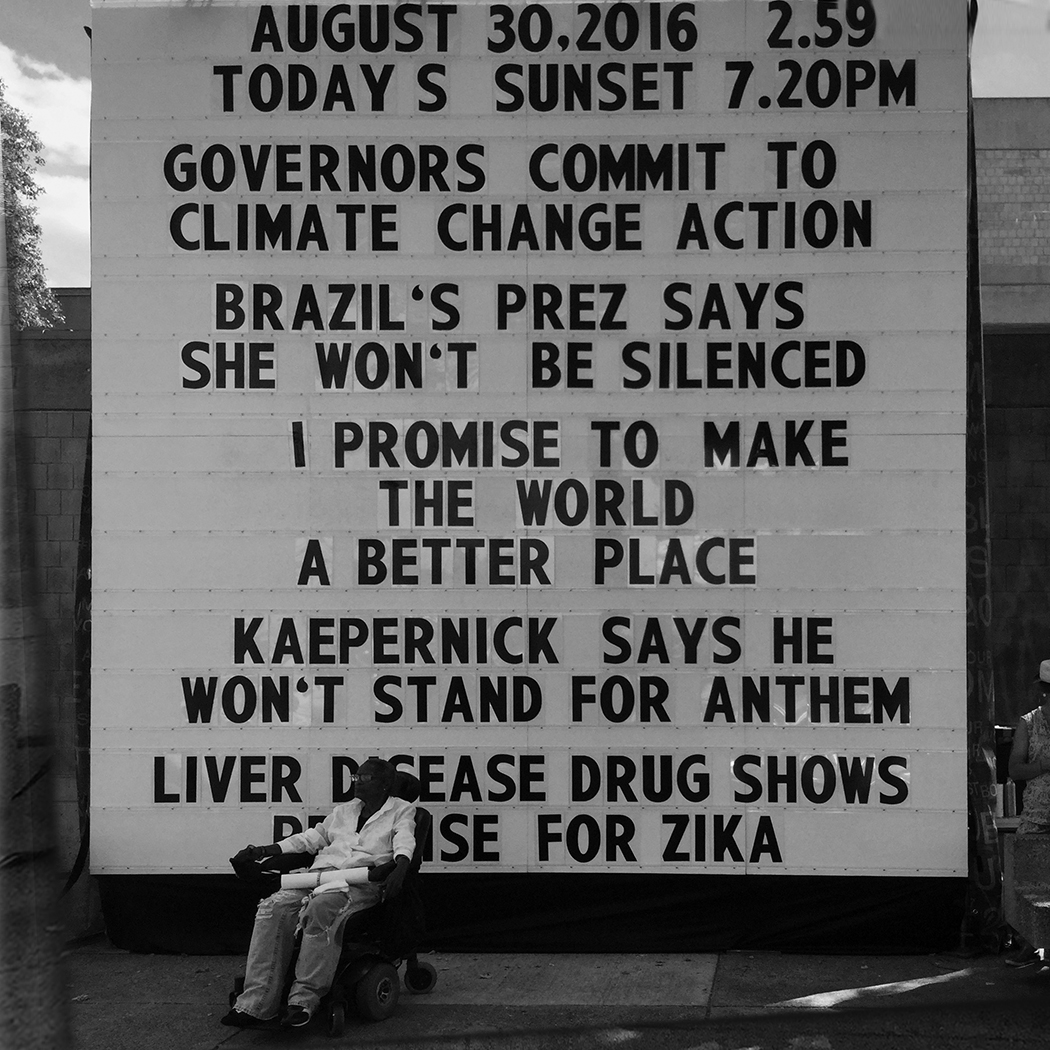

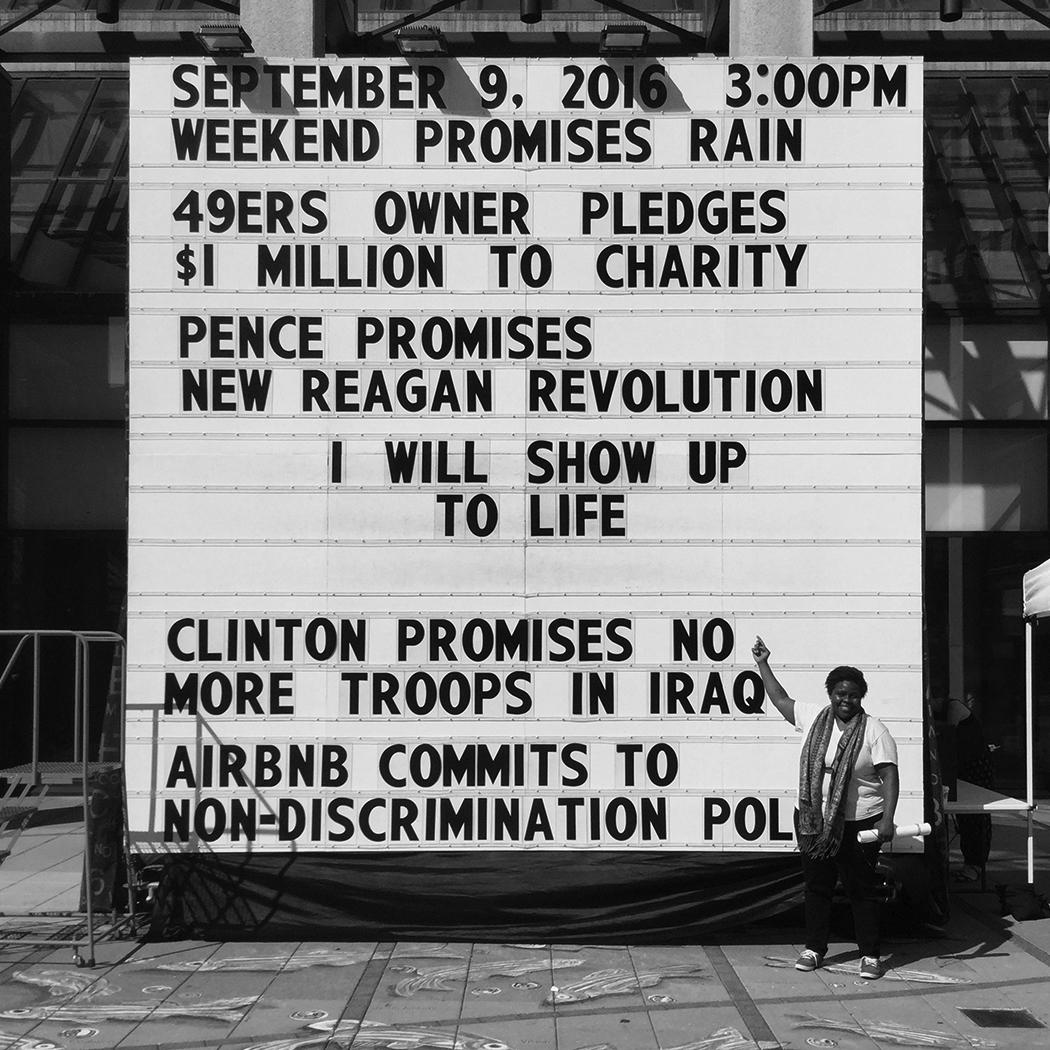

A bell chimes. “We have a promise” is loudly announced, followed by humble applause and a burst of activity. With the help of a ladder, new letters click into place on the billboard-sized marquee. A graphite rub transfers the table’s letterpress words onto two large papers; one departs with the promise-maker, rolled like a scroll, and one is unceremoniously tacked to the museum wall as if to a community news board. The commotion, like a carnival barker, entices curious onlookers to become oath-makers. Alongside the marquee’s ever-changing promises are context clues such as date, time, and daily headlines that evoke other promises: “President Vows to Quarantine Immediately” and “Jets vs. Broncos Promise Must-Watch Football.”

Paul Ramírez Jonas, Public Trust, 2016-ongoing [photo: Wes Magyar; courtesy of MCA Denver]

Two or three facilitators glide around the museum gallery. In 2016, when Public Trust was shown in Greater Boston (Copley Square, Kendall Center, and Nubian Square), it was activated for 21 consecutive days and changed locations every week. Ramírez Jonas developed a script for several people to perform the oath taking: “Now I am an author of work to be reenacted.”

Promissory language has been a significant literary device for centuries. Greek tragedies used oaths to announce the formation of a hero. Such spoken attempts to thwart fate—aka the gods—shifted a character from a passive agent to an active one. In the Bible two unrelated characters may profess an identical oath, thereby constructing a relationship between their stories.1 Because oaths were typically made by evoking God, or with God as witness, they could be seen as a measure of piety. Therefore a promise could craft the reader’s understanding of a character without overtly describing his or her morality. Shakespeare could launch multiple intertwining plotlines from the enunciation of a single oath. Even “baby Yoda’s” guardian in The Mandalorian is a contemporary reflection of our appetite for promissory language. Like boundaries on a field of play, the eponymous character must negotiate difficult decisions to abide by his own stated creed.

The act of promising can be performed somewhat like a joke in a three-person paradigm: one person tells the joke, one is the subject, and one is the witness. In Sigmund Freud’s Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, he explains that one of the qualities of the third party is to understand the language as a joke. The promises of Public Trust are duplicated for display because a commitment being witnessed by others is a method of scaling up accountability. Witnesses can transform a private vow into a public duty. Some museum visitors stepped forward quietly to make a vow, and others did so more enthusiastically, but just as many viewers critiqued from a distance, watching a promise to vote, to be kind, to finish school, with each taking a turn on the comically large marquee. “There is a populism to the piece,” argues Ramírez Jonas. “Ideally [Public Trust] should be outside, so ‘the public’ looks like our country.” He notes that when the work is presented inside a museum, such as at MCA Denver, there is a narrower range of promises. “In Boston, someone was acting erratically in line, almost violent. I walked up to him and hugged him. He calmed down and left. He came back days later and apologized, confessing he was very high. He then got in line and made a promise to be a good father. That moment would never happen inside a museum. The museum is a gate.”

Paul Ramírez Jonas, Public Trust, 2016-ongoing [courtesy of the artist]

Paul Ramírez Jonas, Public Trust, 2016-ongoing [courtesy of the artist]

Many of Ramírez Jonas’ previous works are explorations of trust. Mi Casa Su Casa (2005) and Key to the City (2010) involved granting strangers access to private and public property with the exchange of a simple metal object. In Key to the City, 24,000 keys were distributed. They opened things including a chapel, a kitchen, and a cemetery, transforming a symbolic recognition into a literal act of generosity and vulnerability of which anyone was worthy. Ramírez Jonas notes that half of the country today doesn’t trust the other half, but when the interaction is one-on-one, at the table of Public Trust, it exists. “When a storm is coming, we come together to sandbag, but when discussing global warming we seem unable to do anything. We lost the ability to scale [up trust],” the artist laments. This inability wasn’t always the case. Sumerian records show that Hammurabi’s law considered the oath so effective, if a person accused of a crime made a declaration of innocence, freedom could be granted. According to historian David Silkenat, surrendered soldiers who vowed not to fight again in the American Civil War could be granted parole. But are everyone’s words weighted the same? Does the efficacy of the oath rest in its consequences?

When Republicans blocked the confirmation hearing for President Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland because of its timing in the administration’s final year, Senator Lindsey Graham stated, “I want you to use my words against me. If there’s a Republican president in 2016 and a vacancy occurs in the last year of the first term, you can say Lindsey Graham said, ‘Let’s let the next president, whoever it might be, make that nomination,’ and you could use my words against me, and you’d be absolutely right.” Party colleagues did not admonish Graham when he reversed his promise in 2020. Instead of a curse, or lightning strike by the gods, it is the reaction of one’s peers that indexes the weight of a broken oath. In a few weeks, Public Trust will be closed, crated, and shipped elsewhere. Vows will disappear from the prominent museum wall, to be recalled only by a few people or maybe none at all. Is a joke still a joke if the comic is alone in the club? Is the oath in play when the witness no longer wants to referee?

Paul Ramírez Jonas, Public Trust, 2016 [courtesy of the artist and Galeria Nara Roesler, and MCA Denver]

Immanuel Kant observed that if breaking promises became universal, no one would agree to accept a promise, and it would disappear, along with morality. Such an outcome would argue that what is moral is the same as what is socially normal. However, something can be legal and not moral.2 Consensus around accountability and expected behavior has shifted. For example, consensus exists that the Iraq War was a disaster and that President George W. Bush lied about weapons of mass destruction. Writer Michelle Goldberg notes, “No such consensus will be possible about Trump—not about his abuses of power, his calamitous response to the coronavirus, or his electoral defeat. He leaves behind a nation deranged.” 3

The difference between an oath in Public Trust and one in motion on a national scale is the impact. Arguably, if a promise-maker does not finish school or fails to be kind, it is distinct from an elected official violating a vow to achieve better healthcare for millions or increase educational funding. A promise can keep track of gains or losses in the philosophical theory called scorekeeping, in which a common ground exists among a set of propositions that all parties agree to be true. If an assertion is made and no objections are offered, that assertion can move the common ground. But American political and cultural common ground is fractured like a puzzle dramatically swept off the kitchen table by a frustrated hand. Consensus is now conjecture. The disorientation of this space recalls Galway Kinnell’s short poem “The Vow” (1989), in which the lover (or promise-breaker) leaves, but the brokenness stays, and all affinity for that person only strengthens and dignifies the suffering.

Public Trust is like a finger in the air, gauging cultural currents. It does not address whether the chaos of recent years has been the result of broken promises. Critics, poets, or philosophers are not oracles. If they were, it would mean we are all like Oedipus or Achilles, our fates engraved and our efforts heroic but futile. Public Trust underscores that vows are corruptible. If the ground shifts beneath the promise-maker, the witness, or the oath’s subject, that slippage can threaten the nature of the oath, but that is different from a lie documented and notarized as true. An oath is also an act of trust that acknowledges what has not been done and what still needs to be achieved.

***

Public Trust is included in the exhibition “Citizenship: A Practice of Society” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, on view through February 14, 2021.

Kealey Boyd is a writer and art critic. She is a regular contributor to Hyperallergic, and published with College Art Association (CAA Reviews), Artillery Magazine and others. She is the art consultant to the national literary journal, Copper Nickel, and a lecturer in Art History and Theory at Metropolitan State University of Denver. Her research interests include methodologies for interpreting painting and other visual forms as an integral element of political and cultural discourses.

References

| ↑1 | Yael Ziegler, Promises to Keep: The Oath in Biblical Narrative (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2008), 16. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Herbert J. Schlesinger, Promises, Oaths, and Vows: On the Psychology of Promising (New York: The Analytic Press, 2008), 2–3. |

| ↑3 | Michelle Goldberg, “Just How Dangerous Was Donald Trump,” New York Times, December 14, 2020. |