Heba Y. Amin, Online Book Launch | Heba Y. Amin: The General’s Stork (screenshot) [courtesy of Vimeo]

Passenger—Migration Patterns on the Living and Those of the Dead

Share:

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) of Toronto holds the world’s largest collection of passenger pigeons (Ectopistes migratorius). Various sources claim that the passenger pigeon may have been the most numerous species of bird on the planet—before the arrival of colonial forces to what is today known as North America, that is—with populations as high as five billion during the 19th century. The bird was known for its massive flocks, which “darkened the skies for hours.” In 1866 a single flock over Ontario was described as being a mile wide, 300 miles long, and taking 14 hours to pass overhead. This avian cloud was so impressive that author and naturalist Aldo Leopold called it a “biological storm.” Several theories exist about what led to the passenger pigeon’s extinction, which took a mere half century; all of them have to do with human intervention. One permeating theory is that the bird existed in large numbers because, like plankton, it could thrive only in a massive swarm. Once numbers dwindled, its social and procreative abilities vanished. Another theory is that the birds exhibited an unusually small variation in genetic diversity—stemming from an accidental population boom—and were headed for a natural crash in numbers. Regardless of such theories, the bird’s extinction coincided with its massive slaughter by humans for food. The nickname passenger comes from the French pigeon de passage and refers to the birds’ mass migration patterns.

In 2016, while resident at the ornithology wing of the ROM, I noticed a peculiar fact: The passenger pigeon collection consisted mainly of gifts by locals. Museums document the origins of such specimens by attaching small paper tags to the birds’ feet. These pigeon specimens came from several blocks—or several miles—away. Their travel from capture to museum was brief, and it tells a story of a different Toronto, where one could hunt birds mere blocks from the city’s main streets. These dead birds, now flocking in the museum, tell local stories about local economies and social ecologies. But other species had a far longer journey. The majority of winged specimens in the ornithology gallery at the ROM have traveled extensively through a global network of museums and display cases since drawing their last breath. One bird, collected in Indonesia in 1960 and placed on display there, was soon sold to a museum in Delhi (1965), and then to the British Museum (1985), where it was later de–accessioned and sold to the ROM in Toronto (1992). The cendrawasih, a bird of paradise (Paradisaea raggiana), does not traditionally migrate. Rather, the bird adapts to the island it inhabits and hybridizes with other birds of paradise, thereby becoming a different species. In death it follows a necro-migratory path. First collected under a tree in New Guinea, this specimen made its way through a colonial network—one that gradually extracts life, connection, and meaning—into archives, and through an increasingly complex system of evaluation that ends in a drawer in Toronto, where I examined its tags.

Heba Y. Amin, Online Book Launch | Heba Y. Amin: The General’s Stork (screenshot) [courtesy of Vimeo]

Millions of dead birds follow such new migratory paths, which draw capital from the south and the east into the north and the west. Often, these paths consolidate, convene in the centers of the colonizing empires—London and Paris—for a few years, or decades, before moving on to museums in the new world. These routes are not the birds’ natural flyways. They are new paths toward a capitalist archive that usurps purpose from the world it exploits. In her Paprika! magazine essay “The Archives Need to Breathe,” Chanelle Adams writes, “Jurisdiction over biotic resources, trash or treasure, extends beyond the ethics of recycling paper trails of colonialism. Exploitation of natural resources of former, overseas territories continues. These operations are justified by the paradoxical logic that resources must be extracted, cataloged, and named in order to conserve them.” It is well documented that racist politics develop not only through the brutal subjugation of others but also hand-in-hand with systematic and rigid hierarchical thinking in general. Many European thinkers, once revered and now understood as problematic, have invoked the “laws of nature”1 to justify some of their oppression of others. By conflating the flyways of capital with the natural migratory pathways charted by birds and the practices of ecologically minded artists, I wish to examine the ideological praxis that demands our relationship with “natural law” be restricted to metaphor or economic pursuit.

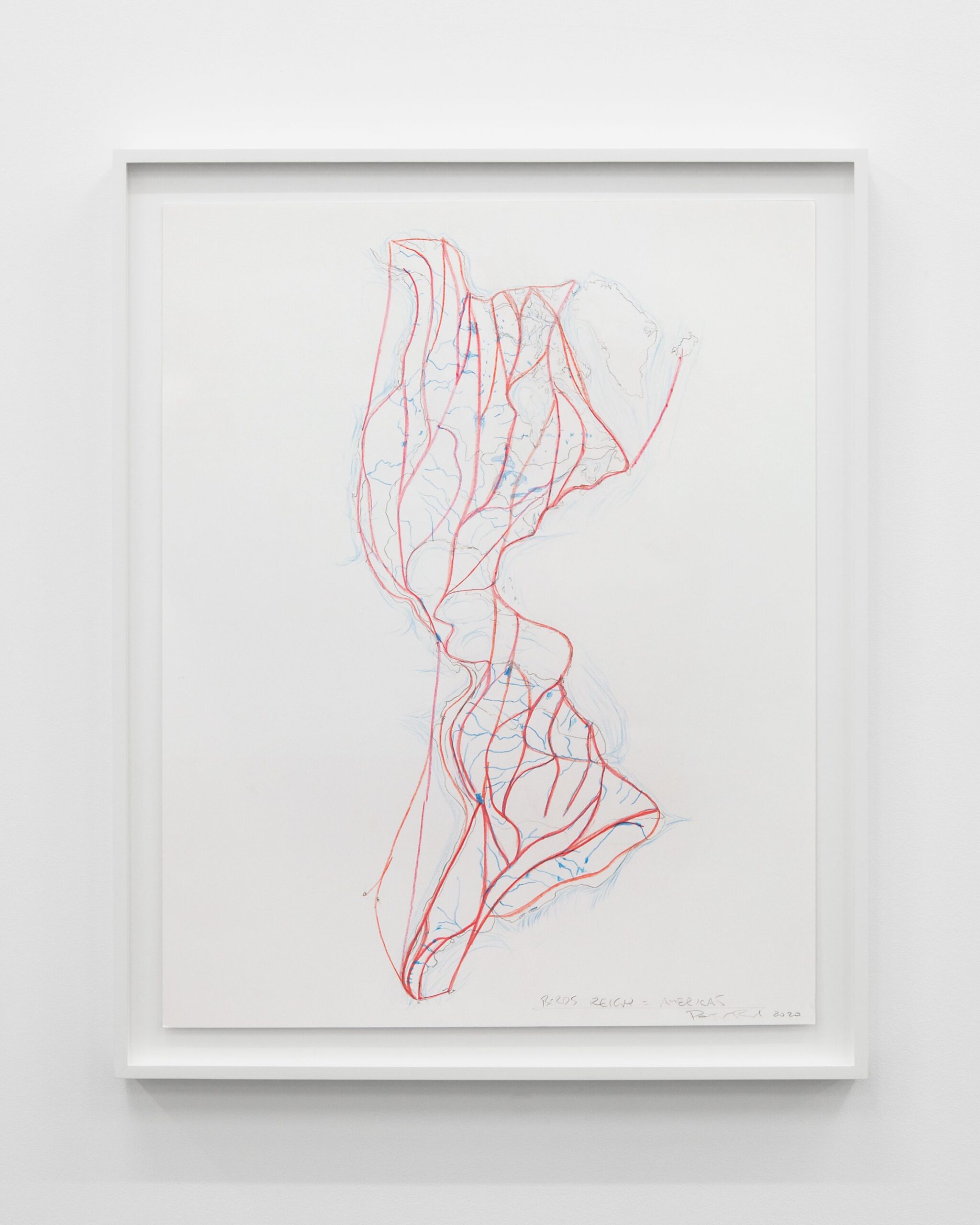

Peter Fend, Birds Reign – Americas, 2020, pencil and coloured pencil on paper, 24 x 18 inches [photo: Jens Ziehe; courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss]

Although on the surface Marx’s analysis of the crisis of the earth (soil) offers promethean solutions to the tensions between economy and ecology, nothing could have prepared communists for the ecological disaster that would be revealed in the aftermath of industrialization on a mass scale. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, artists in Eastern Europe were communing with nature as a way to demonstrate intellectual freedom against a backdrop of restrictive nationalistic parameters applied to painting and sculpture, and eventually to performance, film, theater, and music. The unpredictability and near-psychedelic diversity of natural forms made it an impossible medium to monitor. To those who were burdened by an increasing demand for ideological purity, nature offered a recourse into a grander narrative, colored by existential concerns. An increasingly obvious ecological crisis demanded collective action that exceeded the capacities of the industrial complex constructed by the movement. In reaction, authorities accused those activists of “anti-socialism.” These tensions exposed an underlying “rift” in Marx’s “universal metabolism,” which assumes that all nature will recover once the world becomes wholly socialist. In the aftermath of this conflict, some of Marx’s more ecologically inclined writings were adopted by the avant–garde, which caused further strife within the labor-oriented movement. The Cartesian gap between economy—the functional management of the environment (or the home) and ecology—and its underlying mind-logic undermined the fragile façade of collective utopia that powered the movement.

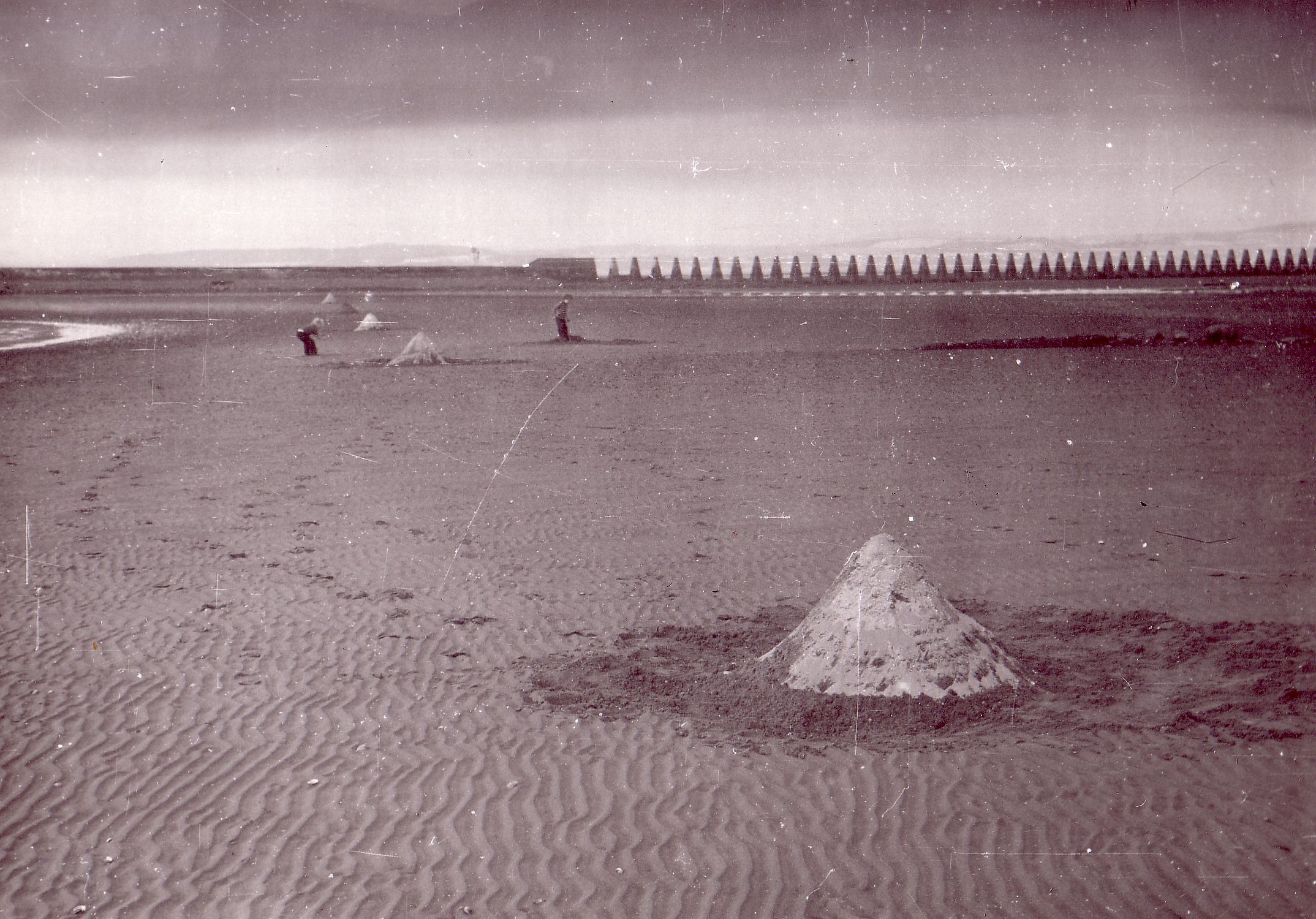

Barbara Kozlowska, documentation of Borderline (Action of the Sea and Five Colored Cones), Edinburgh, Scotland, 1973 [photo: Zbigniew Makarewicz; Courtesy of Zbigniew Makarewicz & Arton Foundation, Warsaw]

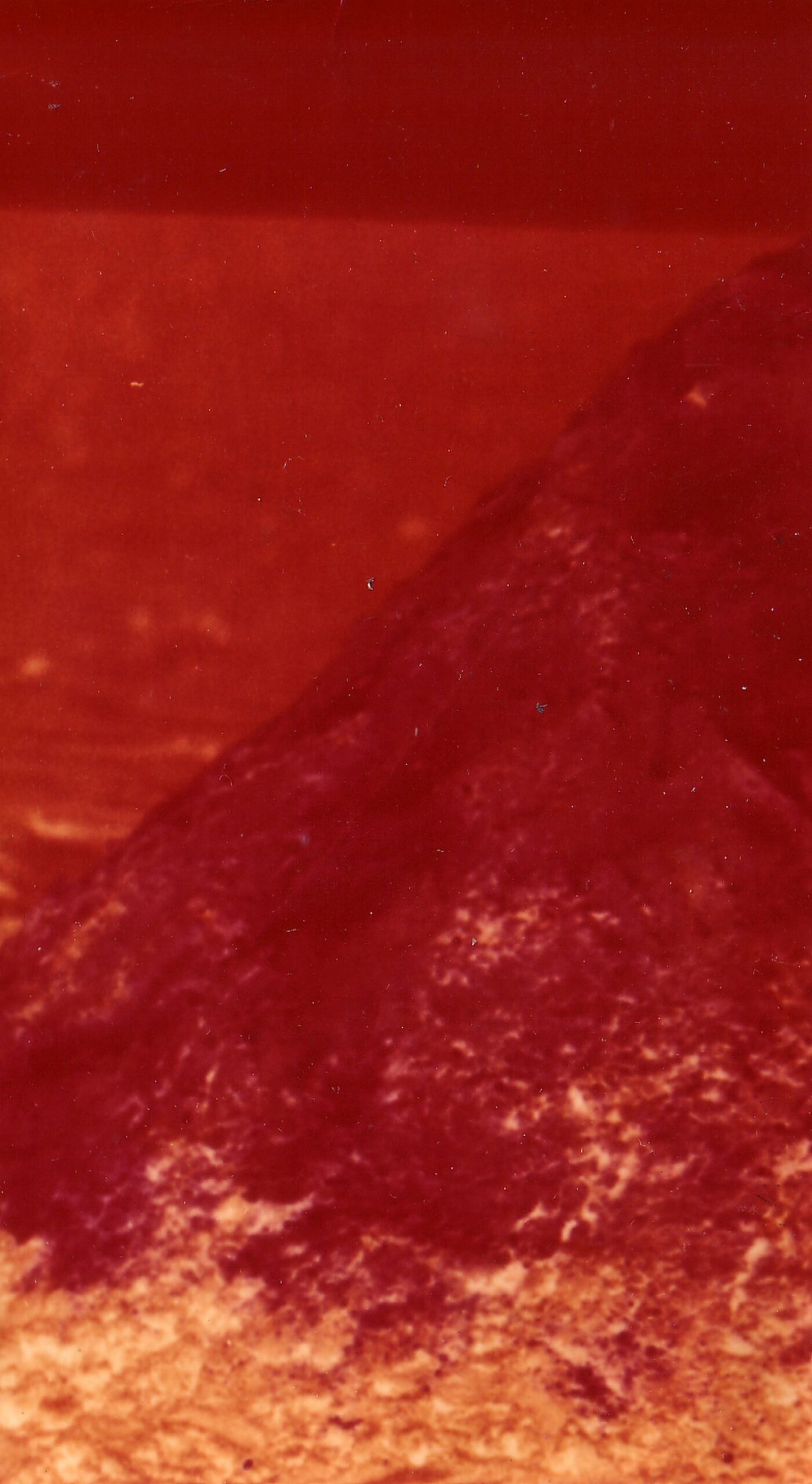

In a 1970 bird’s-eye–view photograph, a red streak colors a sand dune that culminates in a cone. At the image’s top left, there appears to be a body of water. The scale of the streak is revealed by nearby footprints. Begun in 1967, and continued until the artist’s death, Borderline is an earthwork by Polish conceptual artist Barbara Kozłowska. In this work, Kozłowska has drawn an extended line, intended to circumvent the globe from east to west. The line is connected by small points of reference: Sand cones of her own creation mark where land meets water—a small attempt at her own self-determined migration route. That course charts a new pathway around the globe, making visible the arbitrariness of political borders while leaving little trace for the government to complain about. Often wind and water devoured the figures soon after their creation.2 Yet with its erasure, the artistic gesture enters the realm of possibility. New lines can still be drawn, even if only in the sand. They become, as Malgorzata Dawidek Gryglicka observes, “a track running from one point coded by history to another.”

Barbara Kozlowska, documentation of Borderline (Action of the Sea and Five Colored Cones), Edinburgh, Scotland, 1973 [photo: Zbigniew Makarewicz; Courtesy of Zbigniew Makarewicz & Arton Foundation, Warsaw]

In 1976 artist Peter Fend wrote, “Agriculture ends, Art takes over.” Founded by Fend in 1980—along with Colen Fitzgibbon, Jenny Holzer, Peter Nadin, Richard Prince, and Robin Winters—Ocean Earth Development Corporation (OEDC) began in the collective’s New York–based office. It was conceived as an instrument of the environmental movement—intended to elaborate upon the ideas of such artists as Joseph Beuys, Robert Smithson, and Gordon Matta-Clark by creating “useful,” real-life versions of these artists’ projects. The OEDC also provided art services to nonclients, such as the administrative divisions of various governments, political parties, and official environmental bodies. In Fend’s view, the world would benefit from accepting this infrastructure, and from developing such projects as earthworks, because art and artists could then be put to “proper use” by operating and trading in “realities” as efficiently as they do in metaphor. In this way, OEDC rebelled against the limitation of artworks to surfaces and spaces of display that are easily manipulated by capital.

Barbara Kozlowska, documentation of Borderline (Action of the Sea and Five Colored Cones), Edinburgh, Scotland, 1973 [photo: Zbigniew Makarewicz; Courtesy of Zbigniew Makarewicz & Arton Foundation, Warsaw]

Ocean Earth officially launched in 1982 with an exhibition titled Art of the State—a play on the phrase “the state of art”—at The Kitchen in New York. The exhibition consisted of displays that, at the time, were new: satellite images of contested places such as the Falklands, Beirut, and the Caribbean. Like Kozłowska’s Borderline, OEDC’s first exhibition took advantage of an equalizing gesture of the bird’s-eye view, which “marked an important shift from the observational techniques attuned to human perception in modern (art) history—a jump from the human eye into the all-seeing eyes of satellites, first enabled by the military use of aerial photography in the 1930s.” In a phone conversation, Fend told me that satellite imagery can be considered a work of art: “History painting is also the satellite imagery of some war zone.”

Fend’s recent publication Africa-Arctic Flyway: Physiocratic States (2022) elaborates on his strategies of organizing the planet according to hydrology and through pathways of watershed migratory routes, rather than according to national borders. Fend builds upon the concept of physiocracy—the “rule of nature,” an 18th-century school of economy, foundational to most economic thought, and characterized by the idea that governments should not interfere with natural rules. Whereas mercantilists considered wealth to consist of gold and coin, physiocrats insisted that wealth is manifest in the earth through its cultivation. Using mechanisms developed by extractive industries, Fend’s proposed method exemplifies his vision of replacing fossil fuels, dams, nuclear power, and industrial farming with art, architecture, and science in hopes of conserving the world’s wildlife, and to focus upon restoring wetlands and flyways. Fend developed other organizations that provoked government in official and unofficial ways, often in a manner intended to make viewers question whether provocation has become part of the performance. His own writings often mention the FBI and other government agencies that get in the way of his research. In later writings, it becomes apparent that, to him, sites of conflict and extraction are already artworks. Flyways become information highways, and the borderlines connecting sites of conflict and extraction encompass metaphorical terrain. They therefore present real artistic possibilities that can potentially be managed by artists.

Peter Fend, Birds Reign – Eurafrica, 2020, pencil and coloured pencil on paper, 24 x 18 inches [photo: Jens Ziehe; courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss]

Peter Fend, Birds Reign – East Asia, 2020, pencil and coloured pencil on paper, 24 x 18 inches [photo: Jens Ziehe; courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss]

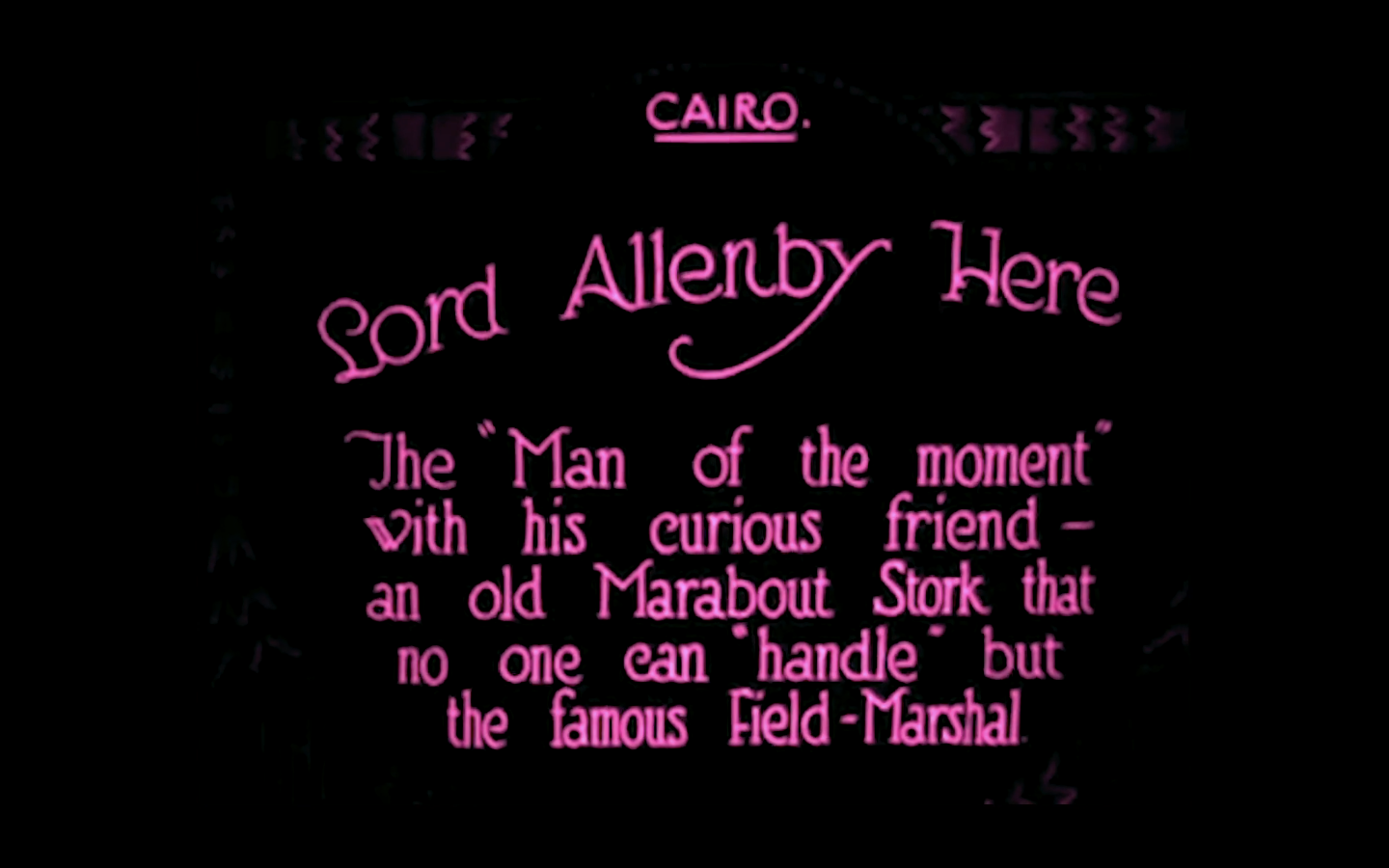

This metaphorical discourse of natural elements, plants, flyways, and wetlands is rooted in deep, existing entanglements of animal passageways with military ones. In 2013, Egyptian authorities arrested a stork for espionage. There is a history of animals being used as spies. Notably, pigeons used as camera carriers did work now done by drones. A project dubbed “acoustic kitty” planned for the launch of a feline spy into the Kremlin but failed when the trainee was hit by a taxi. In 2011 an Israeli vulture was arrested in Sudan. The stork— which had been equipped with a tracking device to help conservationists identify changes in migration patterns—was completing a flyway path from Hungary to the Lake Victoria Basin in Africa, which is bordered by several countries. The bird flew through Israeli airspace into Egypt, where it was dramatically captured by a fisherman in a citizen’s arrest. Artist Heba Y. Amin details the occasion in her multiform project The General’s Stork. Echoing Fend, Amin states:

“We’ve begun to dismantle the linear perspective. The mathematics of art, as put forth by Italian Renaissance painters and architects, no longer deals with the horizon or the vanishing point but rather [with] the detached, observant gaze of god’s-eye view …. The aerial view has become the new norm, as technological tools of surveillance become seamlessly embedded within our contemporary landscapes …. The language of occupation and colonization has been written into the visualization of landscape.”

The animal’s arrest coincided with a shady election and an insurgency. Despite the fact that the flyway followed by the stork is a common one for this type of bird, the story is complicated by its confluence with the comings and goings of colonizing powers. The bird’s migratory destination has long been used as a military base for, in turn, the Americans, the British, and the Soviets, thanks to its remoteness and an alignment with advantageous angles on North Africa.

Heba Y. Amin, Online Book Launch | Heba Y. Amin: The General’s Stork (screenshot) [courtesy of Vimeo]

But storks were not the only flying objects with a history in the area. In 1917, after some unsuccessful attempts to take over Gaza, General Edmund Allenby, a commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, sought to conquer Jerusalem by air. Amin references this episode in The General’s Stork. Convinced by a biblical prophecy in Isaiah 31:5, which reads, “as birds flying, so will the lord of hosts protect Jerusalem,” Allenby ordered the maximum number of planes available to fly over the city—his own biological storm, of sorts. Amin states, “It is said that, at that time, the Turks had never seen as many planes in the sky and [they] were terrified by their presence.” The planes dropped leaflets that read, “Surrender the city today—Allenby.” According to Amin, Allenby could be read in Arabic in only one way: Al-Nabi, which in Arabic means the Son of God. Coincidently, the Ottomans had their own prophecy that, one day, the son of God would demand the city. On that occasion, the prophesy warned, they must deliver it at once. The people of Jerusalem surrendered, which set the scene for a British mandate that would morph, midcentury, into the State of Israel.

Lord Allenby famously had a pet stork, with whom he had made several media appearances. Upon its release, the stork accused of spying was shot down by the very people who first captured him. They proceeded to eat him. In doing so, Amin asserts, “they had consumed their paranoia.”

Amin’s story cautions us against constructed histories that justify oppression as a consequence of natural law. In the current political climate, artists face an increasing pressure to create work with real-life consequences, ostensibly to improve social circumstances. One recurring question among works that concern social justice, the environment, and anti-war sentiment is asked in refrain: “What is at stake?” A subject of high-class capital, the art market is heavily indebted to the ravaged planet it continues to degrade. But when we talk about restitution, we often neglect true biotic claims to justice. Birds, rats, seas, and winds are ceaselessly contending to shape the physical landscape while we struggle to determine their metaphorical agency for the cultural world of humanity. What chance did the Ottomans have in the face of a biological storm—the word of God darkening the skies over North Africa?

Would becoming an earthwork save Lake Victoria from transformation into a full-fledged military base? In recent decades, droves of people were forced to leave their homes and move from east to west. Unlike Kozłowska’s traces, theirs became permanent—worn paths of hardship. Every day, masses of people are forced to migrate away from military conflict in search of respite. Such patterns of migration reveal the necromantic desires of the West to extract, collect, appropriate, and name not just birds but also people, languages, politics, and cultures. What traces constitute an archeology of meaning?

Heba Y. Amin, Online Book Launch | Heba Y. Amin: The General’s Stork (screenshot) [courtesy of Vimeo]

Heba Y. Amin, Online Book Launch | Heba Y. Amin: The General’s Stork (screenshot) [courtesy of Vimeo]

Can migratory paths offer clues about our recent past (and quickly approaching future)? Deleuze and Guattari wrote on the process of de-territorialization and re-territorialization as transformative contextual practices that create new social spheres. At the intersection of museological procedures, military operations, and artistic practices that mitigate the natural world is a philosophical thread that binds these entities to the history of movement at large. Winged species’ habits presage larger patterns that dictate the lives of people, art, and artifacts across landscapes and centuries, encompassing prophetic visions, colonialism, and all of capital. Above all, they reveal a tension between the migration patterns of the living and those of the dead. By tracing the capital flyways that channel the mass migration of specimens, we might uncover how other routes that direct our species and affect life on Earth determine the memory of the world.

Xenia Benivolski curates, writes, and lectures about sound, music, and visual art. Her writing appears in such academic journals and art publications as e-flux journal, Artforum, Art-Agenda, Infrasonica, and Flash Art. She is editor and curator of You Can’t Can’t Trust Music at e-flux.com, a research project connecting sound-based artists, musicians, and writers to explore together how landscape, acoustics, and musical thought contribute to the formation of social and political structures. Benivolski contributes to the Worker as Futurist project at Lakehead University.

References

| ↑1 | 1 Austrian composer Heinrich Schenker—whose systematic notational structures have served as the foundation of modern melodic, harmonic, and tonal music—was a fascist who supported the categorization of races with equal fervor to his systematic categorization of notes. Schenker saw compositions as living organisms. Moreover, he believed in the inequality of tones. In “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame,” for Music Theory Online: A Journal of the Society for Music Theory, Philip A. Ewell writes, “Indeed, Schenker’s hierarchical beliefs on race are so intimately connected with his hierarchical views on music, one wonders which motivated which.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | 2 In Feminism and Technoscience, theorist Donna Haraway writes, “‘To figure’ means to count or calculate, and also to be in a story, to have a role. A figure is also a drawing. Figures pertain to graphic representation and visual forms in general, a matter of no small importance in visually saturated technoscientific culture. Figures do not have to be representational and mimetic, but they do have to be tropic; that is, they cannot be literal and self-identical. Figures must involve at least some kind of displacement that can trouble identifications and certainties.” |