Cornell Labs Panama Fruit Feeder Cam at Canopy Lodge

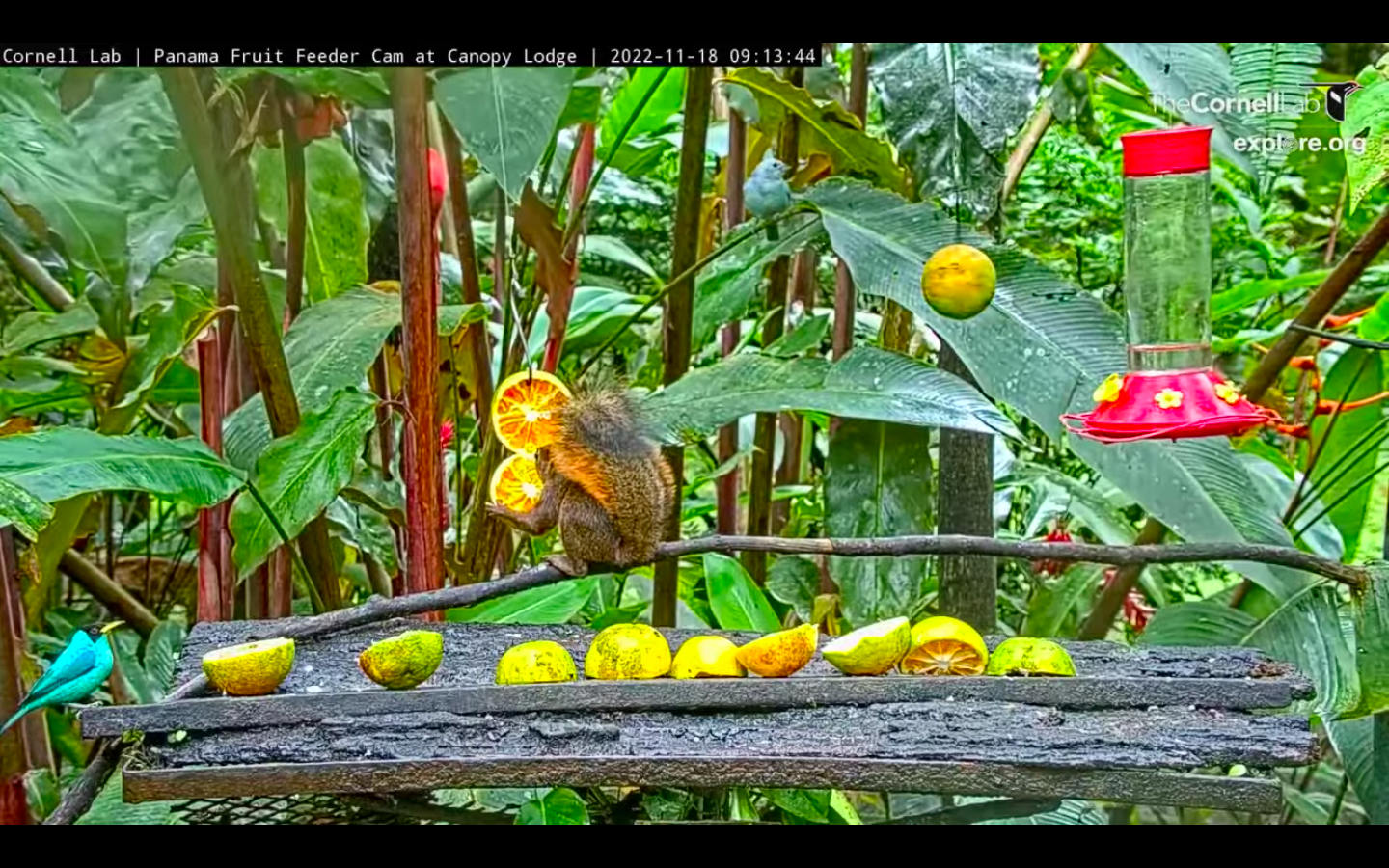

Panama Fruit Feeder Cam at Canopy Lodge (screenshot), 2022 [screenshot courtesy of Cornell Lab Bird Cams and Youtube].

“We have to become humble in front of this overwhelming misery and overwhelming fornication, overwhelming growth, and overwhelming lack of order. Even the stars up here in the sky look like a mess. There is no harmony in the universe. We have to get acquainted to this idea that there is no real harmony as we have conceived it. But when I say this, I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it. I love it. I love it very much. But I love it against my better judgment.” —Werner Herzog, Burden of Dreams

Share:

I have watched the Panama Fruit Feeder Cam at Canopy Lodge, passively, almost every day for seven months. Like Wordle and cigarettes, it was never supposed to become a habit for this long. Yet here we are. The Fruit Feeder rests comfortably in the bottom right corner of my second monitor—a small, lively scene nestled below my Outlook calendar.

A collaboration between the Canopy Lodge, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and explore.org, the Fruit Feeder Cam is a 24-hour live stream featuring the verdant vegetation and wildlife in the lodge’s surrounding forest. Explore.org hosts many such live streams, including the Mississippi River Flyway Cam, the Giant Flying Fox Cam, and the popular Two Harbors Bald Eagle Cam. All these live streams have their own charms and dedicated audiences, but the Panama Fruit Feeder Cam is a clear stand-out. It consistently draws above-average viewership, and the reasons are obvious.

Even without the presence of a rufous motmot or gray-cowled wood-rail, the Fruit Feeder Cam captures a lovely scene. Luscious greenery frames a low wooden platform adorned with fruit. Halved limes are often placed face up on the platform—to best display their fleshy gifts—whereas bananas and lemons swing lazily from metal hooks hung, presumably, on the branches above. Occasionally, mangos and papayas join the happy party and are often devoured quickly. Above and to the right of the camera hangs a hummingbird feeder that gets jostled frequently by eager blue-chested hummingbirds and the occasional optimistic squirrel. In the wet season, rain renders the whole scene slick and glistening; otherwise, the sun casts its hazy rays through the canopy.

Panama Fruit Feeder Cam at Canopy Lodge (screenshot), 2022 [courtesy of Cornell Lab Bird Cams and YouTube]

Panama Fruit Feeder Cam at Canopy Lodge (screenshot), 2022 [courtesy of Cornell Lab Bird Cams and YouTube]

Compositionally, the Fruit Feeder feed resembles still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age—posed yet messy, sensual, dramatic, and half-eaten. The Cam’s color palette is vibrant with rich greens, yellows, and oranges. Of course, unlike still lifes of old, the scene consists not of luxury foods and wares but of the natural—albeit casually staged—abundance of the Canopy Lodge. Furthermore, unlike a static still life, the Fruit Feeder is quite alive. Although the Cam undoubtedly offers a pretty picture, even in its quietest moments, the real stars of the show are its vivacious participants.

The Fruit Feeder can be viewed as a kind of durational performance art. Its participants may be unaware of their roles, but they perform their daily dramas nevertheless. Fights between peckish birds over the best bit of mango or the prime perch on a branch often rattle the otherwise tranquil setting. The overwhelming growth and decay of the surrounding forest and the exhausting, relentless tussle between life and death infuse the scene with a kind of madness. It is less a fight against entropy and more of a complete capitulation to it. Carefully placed limes are, ultimately, no match for the fury of life in the forest.

Panama Fruit Feeder Cam at Canopy Lodge (screenshot), 2022 [courtesy of Cornell Lab Bird Cams and YouTube]

Rarely do the squirrels, iguanas, and brightly colored birds that pop in and out of frame act at ease. Their eyes dart. They are easily startled. The most spectacular collared aracari might jump onto the platform and jump away just as quickly, as if fleeing hot coals. In the morning, fruit appears, then it is eaten, then it appears again. Sometimes a banana will hang from a hook all day, slowly picked away, slowly rotting. Sometimes the banana is gone in minutes, torn to bits by the violent beak of a toucan. Once the best pieces of fruit are gone, the bugs consume the rest, buzzing in thick clouds above the carcasses. Every day, the same. Every day, different.

Nighttime is a nightmare. The inviting rainbow of colors disappears into black and gray as the sun goes down and the Cam’s night filter activates. The bugs, which during the day appear as black specks against the brightness of the fruit, seem to multiply by the thousands. Once black dots, they now become swift-moving specks of gray. They slam against the camera lens, they fly erratically. Larger insects can be seen crawling along the platform in search of food. The fruit, which has decayed all day in the sun or has become swollen with rain, is well picked over by night. Bits of banana skin and mango lay half-gored to bits. Lemons, barely clinging to their metal hooks, sway in the night breeze. Possums and other eager nighttime rodents are quick to the scene, a two-for-one special of fruit rinds and bug bodies. Bats flicker across the frame and momentarily visit the hummingbird feeder to take a fleeting sip. The sound is unbelievable. Although the Fruit Feeder is by no means quiet during the day, at night it turns into a roaring, shrieking cacophony as hundreds of bugs and animals set their volume to loud. The dawn arrives exhausted.

Panama Fruit Feeder Cam at Canopy Lodge (screenshot), 2022 [courtesy of Cornell Lab Bird Cams and YouTube]

Panama Fruit Feeder Cam at Canopy Lodge (screenshot), 2022 [courtesy of Cornell Lab Bird Cams and YouTube]

Another, more enigmatic character in this performance has yet to be mentioned. I have seen him only a handful of times, but he is a crucial figure. In the early morning, if you’re watching at the right moment, you’ll see a man. He stays near the edges of the frame. He often wears a wide-brimmed hat and gloves. He brushes the ruined fruit from the platform and removes any dangling remnants from the hooks. He replaces the old with the new. Presumably the same man might not do this duty every single day—the Canopy Lodge has a large team—but those times that I have glimpsed these procedures, they are performed by the same man.

I want to talk to this man and find out what he has seen. What world exists beyond the confines of the camera frame? I want to know if he felt the way I did the first time I saw a baby rufous motmot. I want to ask him who is winning in the game of life and death at the Canopy Lodge. I want to ask if he has ever had to remove the body of an animal in the morning, along with the banana peels and lemon rinds.

Panama Fruit Feeder Cam at Canopy Lodge (screenshot), 2022 [courtesy of Cornell Lab Bird Cams and YouTube]

With his furtive placing of fresh fruit, the whole performance begins again, forming a nearly seamless loop. Birds and iguanas and squirrels come together in alternating moments of peace and violence, harmony and chaos. The sun’s heat brings growth and decay; the sunset brings safety and panic. The Cam documents a scene of constant contradiction. But there is a strange comfort in it, all the same. The performers have their own reliable rhythms. Like the dependability and consistency of the planets’ rotation, fruit appears, fruit is eaten, fruit reappears.

Watching the Cam has become a daily practice of sorts, less meaningful than a prayer, but certainly more meaningful than a routine. Over the past seven months, the Outlook calendar that lives as the Cam’s upstairs neighbor on my second monitor has changed to a different kind of chaos—unpredictable and unstoppable. There is no death in the Outlook calendar; only uncontrollable, linear growth. Nothing there is destroyed, only created. But below, a banana peel browns in the rain. A squirrel picks an ant off a mango. Eats it.

EC Flamming is a writer in Atlanta. Her work focuses on the cultural impacts of moving images and contemporary art to explore how media consumption shapes and reflects social relations. She has written for Art Basel, Photograph, ART PAPERS, ArtsATL, Paste, BURNAWAY, Another Gaze, and more. Her work can be found on ecflamming.com. If you have a movie or television suggestion, DM @ecflamming