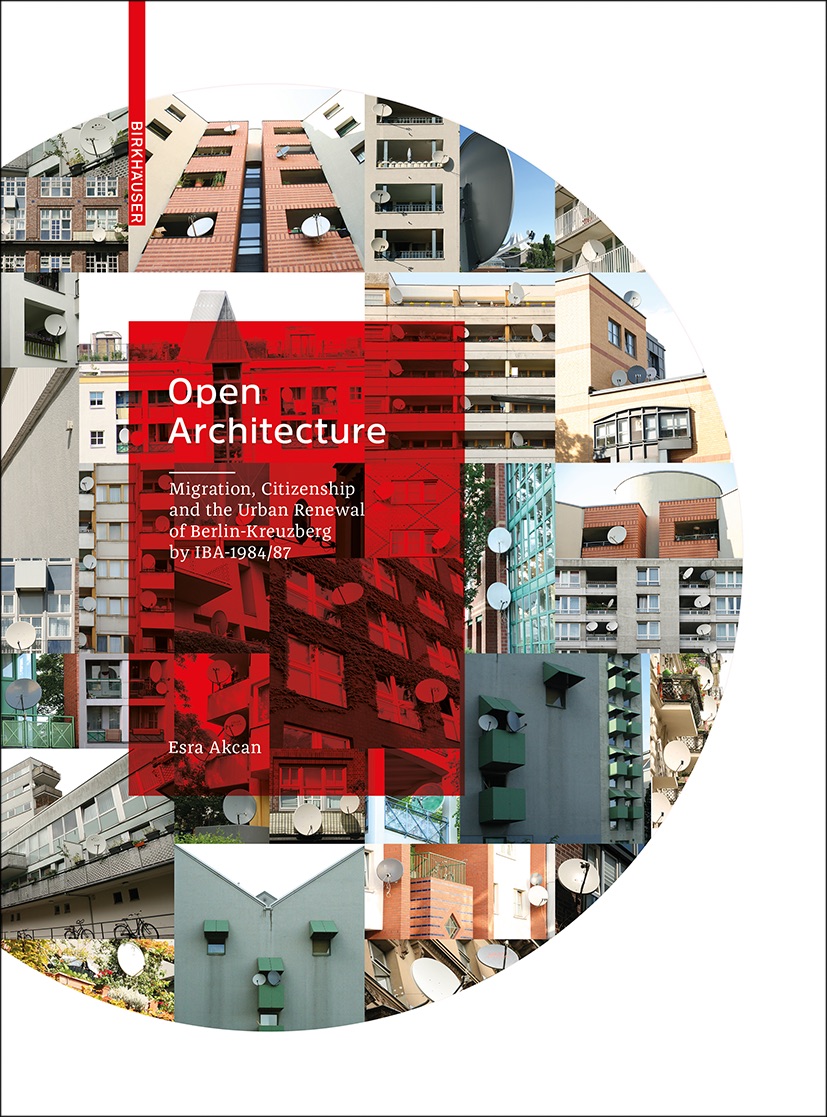

Open Architecture

Image from Open Architecture: Migration, Citizenship, and the Urban Renewal of Berlin, 2018 [photo: Esra Akcan; courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Subjects, Not Objects—Hospitality Through Open Architecture.

Rather than espousing a syncretic approach, architecture has been preoccupied for decades with either global environmental conditions or isolated formalist aesthetics. In her latest book, Esra Akcan manages to activate and integrate artistic formalism with sociocultural performance by elevating diverse current-day and historic narrative into a critical discussion. She decisively reevaluates the language, method, and ethics of an architecturally driven activism at a moment of sociopolitical instability in which the figure of the migrant, again, resurfaces in the cross hairs.

Akcan’s Open Architecture: Migration, Citizenship, and the Urban Renewal of Berlin-Kreuzberg by IBA-1984/87 reveals itself as an academic work of formal inventiveness and passionate advocacy. Anchored by a detailed investigation of the Internationale Bauausstellung Berlin 1984/87 (IBA), the intermittent international building exhibition initiated in 1979 as an urban renewal project for West Berlin, her writing unfurls through time and space with unassuming acrobatic lightness. The book overcomes the challenge of unmuting the exhibition’s many marginalized actors, whether the architecture professionals who built the full-scale exhibition or the migrants who eventually lived in it, filling a conspicuous gap in architecture history in the process.

Since their inception in 1901, IBAs have been instrumentalized as model settlements in German-speaking countries during times of upheaval for the purpose of expressing ideological positions in permanent full-scale building and planning. Among the most impactful antecedents to IBA-1984/87 are the 1927 Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart and Otto Bartning’s IBA 1957 in West Berlin. The latter, a direct response to the monumental Stalinallee (1952–1960) and its status as a beacon of Soviet planning in East Berlin, wove social and building program with modern technology and aesthetics to create a Western model for the city of tomorrow.

Structured in three parts—Open Architecture as Collectivity, Open Architecture as Democracy, Open Architecture as Multiplicity—Akcan’s examination of Berlin-Kreuzberg, or the Harlem of Germany as a 1973 article in Der Spiegel dubbed the borough, takes the reader on a series of explorative strolls and stops, illustrated on a foldout map. The map itself, by charting passages rather than marking points, graphically affirms the experiential dimension and gravity of contextualization critical for encounters with architecture and its inhabitants. The stroller, explains Akcan, “is a dot in virtual space, but one who is also capable of dislocating in time, and one who is interested in archival resources and in traveling to a past when Kreuzberg’s urban renewal took place.” To define “open architecture,” Akcan analyzes seven IBA buildings from which to compose larger trajectories or else to implode the calcified image of IBA-1984/87.

Esra Akcan , “Open Architecture: Migration, Citizenship, and the Urban Renewal of Berlin-Kreuzberg by IBA-1984/87,” 2018

Like Josef Paul Kleihues, the exhibition’s director, Akcan layers the area’s histories in order to unveil their fraught intentions, carving out a “‘physiognomy’ of the area,” as she writes, that both grounds and projects. More crucially, this process becomes integral in unpacking “how legally constructed citizenship status coupled with socially constructed racial or ethnic hierarchies affect urban space and architecture.” Assembling and critiquing multimedia evidence, she leads the reader to deconstruct the ideological agenda that corrupted the exhibition, turning it into a tool for social control of its noncitizens—the abstract economic category under which the Turkish guest workers and refugees fall.

Collecting the voices of residents and architects, citizens and noncitizens, politicians and activists, the author orchestrates them into critical dialogues, declaring that they all “have the same subversive instinct about the bureaucracies in urban spaces.” Through these “touching tales”—which Akcan evokes by way of the labor migrant poetics of Aras Ören’s Berlin trilogy (1973–1980)—Open Architecture dismantles and reconstructs the IBA-1984/87 as a catalyst for straying temporally and geographically into the periphery to discuss the larger notions of hospitality and openness.

“Open” in Akcan’s book title unfolds in its various meanings—“flexibility and adaptability of form, unfinished and unfinalizable design, collectivity and collaboration, participation and democracy, and multiplicity of meaning.” Openness also implies potentialities, which are represented by the unrealized projects for IBA-1984/87 with which she closes her book. Written in the past-tense subjunctive, as if to escape the limitations of history writing, the final chapter interrogates the idea of a history of possibility. By questioning received truths, she narrates “what if” scenarios that reveal new interpretations of “what was,” otherwise impenetrably obscured by an unbalanced representation of the cultural integration and ethico-political spectrum of IBA through its official organs and the media. “The book asks,” she concludes, “what would have happened if the architectural discipline and profession were shaped by new ethics of hospitality toward the immigrant, and calls this open architecture.”

Image from Open Architecture: Migration, Citizenship, and the Urban Renewal of Berlin-Kreuzberg by IBA-1984/87, 2018 [photo: Esra Akcan; courtesy of the artist]

Swiftly and unassumingly, Akcan pulls her readers from historical setup to theoretical, sociocultural, and political intricacies. Her ability to translate a wealth of information into a substance that stays in the reader’s mind makes her a rare literary talent in architectural history writing. And although some of Akcan’s chapters and subchapters peter out in speculation, these sections form a theoretical proposition that, like a question mark, keep the reader thinking, demanding continued engagement.

The clarity and acuity with which Akcan presents the cacophony of German, Turkish, and English voices are matched only by her descriptions of buildings and urban environments. Even readers who are faintly familiar with Kreuzberg or Berlin are catapulted into the streets and court gardens by her ability to convey both detail and broad strokes while oscillating stimulatingly between architectural and sociological description. For instance, her descriptions formally carve out the cuboid mass of Oswald Mathias Ungers’ Block 1 while setting it as the stage of a brutal murder that reflects the sober reality of its sociopolitical makeup. The leitmotif of hospitality that snakes through the book continues Akcan’s investigation of migratory histories and the intricate philosophical nature of hospitality developed in her first book, Architecture in Translation: Germany, Turkey, and the Modern House (2012), by “making a plea for a new ethics of welcoming that would inform open architecture to come.”

Image from Open Architecture: Migration, Citizenship, and the Urban Renewal of Berlin-Kreuzberg by IBA-1984/87, 2018 [photo: Esra Akcan; courtesy of the artist]

The book’s ample illustrations balance Akcan’s analytic descriptions with visual evidence. It includes intimate interior photos by the author herself—their pictorial framing striking the delicate balance between voyeurism and architectural documentation that nevertheless betrays traces of inhabitants. Amid descriptions of the dwellers of John Hejduk’s iconic Kreuzberg Tower, we’re shown both their journey to Berlin and the endemic limitations of the architecture’s functionality. For Akcan these interiors become operative in supporting a feminist architectural history that ought to write more women as so-called resident architects into architecture—“individuals who confirm the openness of architecture by participating in its mutation.” Akcan’s reading aims to undo the essentialist link between domesticity and women while observing how they shape the home.

Extending its theoretical tentacles into the present and posing questions for the future, Open Architecture is more than a historical study. It not only records but reconstructs the ongoing struggle of immigrants and noncitizens in Germany in an effort to underline the importance of public housing for architecture and the sociocultural equality of city dwellers. It is through the voices of the architects, the residents—the sheer effort in collecting of stories and facts—that Akcan is able to advocate for an open architecture that doesn’t reduce the inhabitants of housing blocks to “users” and that does demonstrate their humanity.

Open Architecture, with its innovative methodology and style, becomes a manifesto to propagate not only spaces of hospitality but the writing of “open architectural history.” Open Architecture is Akcan’s creaturely hybrid: “it is the translation of a new ethics of hospitality into architecture,” an important contribution to the writing of feminist architectural history, orienting architectural discourse toward viewing “the inhabitant as a subject rather than an object who is supposed to behave in the way predefined by the author-architect.”