Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019

Lorraine O’Grady, Art Is… (Troupe Front), 1983/2009, C-print in 40 parts, 16 x 20 inches, edition of 8 + 1 AP [courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, NY © 2020 Lorraine O’Grady, (ARS) Artists Rights Society, NY]

“Writing is the art form most closely bound to time, but to layer information the way I perceived it, I needed the simultaneity I could only obtain in space.”

—Lorraine O’Grady

Share:

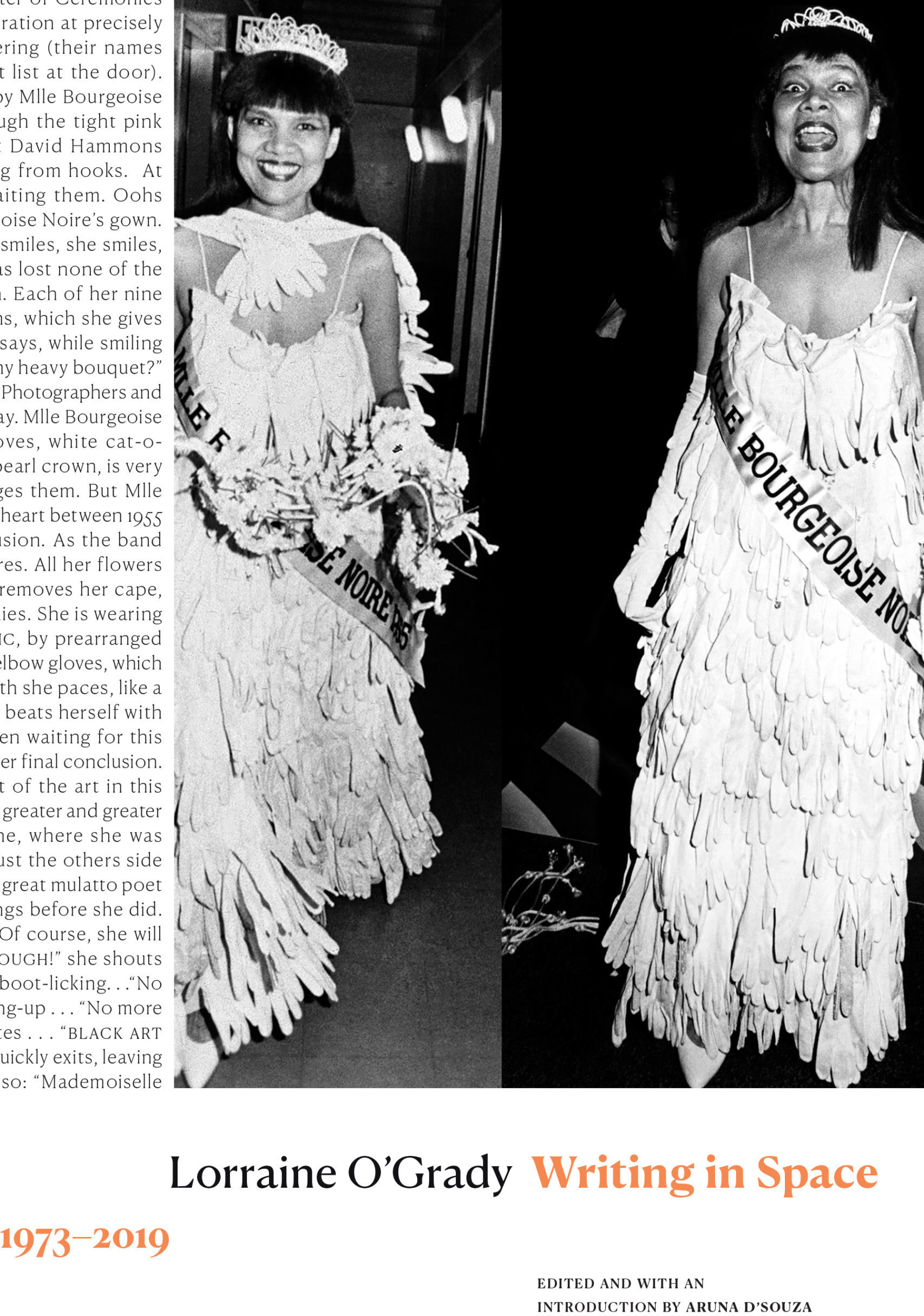

While on a Schomburg Center fellowship in the summer of 2017, I came across Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Costume (1980), arguably one of Lorraine O’Grady’s most recognizable works, in We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85, at the Brooklyn Museum. Although the exhibition was brilliantly comprehensive, Mlle Bourgeoise beckoned to me and captured my attention; I had never seen anything like it. I approached the elegant garment with curiosity, questioning what the amalgamation of weathered ivory gloves and neatly sewn sash signified. I wondered whether the mannequin’s tan, creamy skin tone was intentional. I was, at that time, in the midst of my undergraduate years at Spelman College, and the work evoked memories of how involvement or adjacency to pageants offered students social capital that often became tangible.

O’Grady channeled her early questions about the politics of performance in the West Indian Episcopal Church into an artistic practice that agitates art establishments, particularly ones that disregard Black women’s participation in the avant-garde. The artist draws inspiration from gender, diaspora, and identity-based theories, yet she maintains focus on Black female subversiveness, which permeates her performances, photo installations, and moving images. Her initial professional life—as an intelligence analyst for the United States government, a literary and commercial translator, and rock music critic, before committing to artmaking—reflects a passion for language’s ability to constantly take new forms.

Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019 [courtesy of Duke University Press]

We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85, installation view of Lorraine O’Grady’s “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Costume,” 1980 [photo: Jonathan Dorado; courtesy of Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY]

Writing in Space, 1973–2019—the aptly titled first compilation of Lorraine O’Grady’s writings—is a deeply nourishing account of her life, from the years preceding her full approach to artistry and criticism until recent times. Throughout the collection of writing, O’Grady encourages readers to create, evoking the adage “if you build it, they will come”: “Right now, my goal is to discover and create the true audience, and something tells me that, for a black performance artist of my ilk, this will take a many-sided approach. Because I sense that the true audience may be coming, not here now, I try to document my work as carefully as I can.” Such a collection, 46 years into O’Grady’s exceptional career, reflects how the art industry has long excluded Black women artists. It is a delicate and difficult read, and a manifestation of the many possibilities embedded in thoughtful collaboration between an artist and editor who have been longtime supporters of each other’s work. The introduction, by editor Aruna D’Souza, proved to be an appetizer that left me eager for deeper context:

O’Grady has always remained keenly aware of how the obligation to explain oneself still weighs more heavily on black artists than on white, and may always be so—because, as she recognizes, the demand for explanation and justification from artists of color, especially women, are part of how white supremacy continues to shape the (art) world and its institutions.

The book is organized into sections based on categories. Rather than a more traditionally format-driven grouping of artist’s statements or interviews, the texts are arranged using headings that alternately emphasize form or content. Some of the writings in the first section—Statements and Performance Transcripts—such as “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1955 (1981)” and “Rivers, First Draft (1982)” are theatrical scripts, with the names of players at the beginning. Others are epistolary—such as 2007’s “Statement for Moira Roth re: Art Is …, 1983” and still others are exhibition texts in wall-label format, for example, “Body Is the Ground of My Experience, 1991—Image Descriptions (2010)” The variation in forms, even in O’Grady’s crystal-clear voice, can make following her intricate thought process tricky, but readers can settle into this aspect of the book as they navigate it.

Lorraine O’Grady, Art Is… (Back of Float), 1983/2009, C-print in 40 parts, 16 x 20 inches, edition of 8 + 1 AP [courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, NY, © 2020 Lorraine O’Grady, (ARS) Artists Rights Society, NY]

Lorraine O’Grady, Art Is… (Woman and Girl with Stripes), 1983/2009, C-print in 40 parts, 16 x 20 inches, edition of 8 + 1 AP [courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, NY, © 2020 Lorraine O’Grady, (ARS) Artists Rights Society, NY]

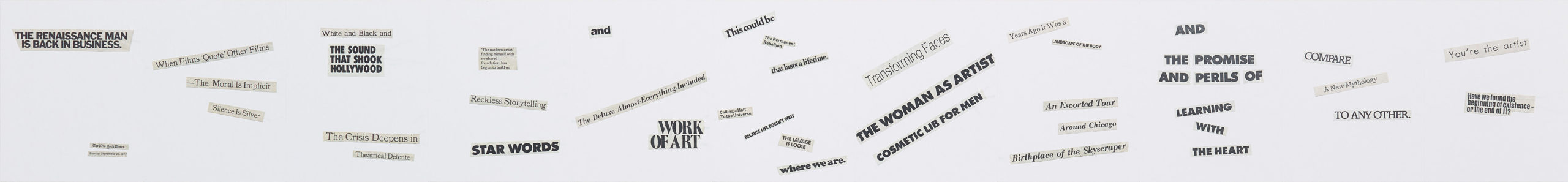

Many included texts are O’Grady’s contemporary responses to works she created decades earlier, such as her interview with curator Amanda Hunt about O’Grady’s 1983 performance work Art Is …. “On Creating a Counter-confessional Poetry (2018)” also builds upon, and more deeply examines, her earliest body of work, Cutting Out The New York Times (1977). O’Grady supplies readers with context that imparts her original intent and reveals an intense longing to revisit a lost version of herself, decades later:

The shock of entering the art world in 1980 had caused a distortion in what I produced, it seemed, away from the more experiential and toward the more argumentative. I wanted to return to that voice so as to get on with new work. Cutting Out The New York Times … had succeeded in its first goal to make public language private, but it had failed, I believed, in its second goal—to create counter-confessional poetry …. But I thought forty years of experience might correct the failure. And they did.

Lorraine O’Grady, Cutting Out the New York Times, The Renaissance Man is Back in Business, 1977/2010, toner ink on adhesive paper, 11 1/8 x 86 4/8 inches, edition of 8 + 1 AP [courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, NY © 2020 Lorraine O’Grady. (ARS) Artists Rights Society, NY]

Here, and at various other points throughout the book, O’Grady reveals a trust and respect for her past work—and who she understood herself to be when she created it—that reminds others to draw inspiration first from within themselves. She revisits the injustices that served as inspiration for her older work, many of which continue today in varied forms. O’Grady’s comfort in assessing the class-specific notions of her upbringing further establish her as an artist who looks to the past as much as the future.

For many people, passion for an artist’s work leads to a desire to know and understand the person behind the work, to probe the myriad, encompassing forces that affect their work and ability to create. These pursuits are fed throughout the text, and deeply inspired me to form active relationships with artists from across what Paul Gilroy named the Black Atlantic. Aruna D’Souza traverses the past and present to create Writing in Space, 1973–2019, which is likely to remain a significant resource for years to come.

Tyra A. Seals is an emerging curator of African diasporic art and a PhD student in the department of Art History at the University of Delaware. Her research seeks to address the social, political, historical, and economic forces that affect the works of female assemblage artists across the Black Atlantic. Seals is a proud Atlanta native and alumna of Spelman College, where she studied English and art history and graduated cum laude in 2018. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter @thetyratales.