Jes Fan, Sights of Wounding: Chapter 1, installation view, 2023 [photo: Michael Yu; courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong.]

Of Oysters, Roaches, and New Pessimism in Hong Kong

Share:

Arriving at Empty Gallery is always an experience. There’s getting to Tin Wan in the first place a part of Hong Kong that feels like a world unto itself on its peripheral downtown perch along the edge of Aberdeen Harbor. Then there’s the lift that takes you up to the 19th floor of a nondescript high-rise that hosts this two-floor black box space where art functions as the light in the dark. Such was the case with works by Tishan Hsu and Jes Fan, whose solo exhibitions each occupy one floor.

In Fan’s show, Sites of Wounding: Chapter 1, blown glass orbs glow under spotlights as they slump over metal frames and ooze from resin slabs composed to invoke the surface of oyster shells. A pigmented aqua resin vessel holds two glass orbs in Left and right knee, grafted (2023), while fine, pigmented aqua resin sheets are layered like waves to form a square on the wall in Diagram XIX (2023), out of which a glass orb seems to excrete itself. Nearby, square glass sheets are stacked at intervals on a stainless steel tower frame, in C is for you (2023). Each of the sheets was kiln-fired with an oyster shell so that it holds the impression of its shape, as well as ashy traces of what once was.

Jes Fan, Diagran XIX, 2023, aqua resin, glass, pigment, metal, 12 x 7.5 x 15 inches [photo: Pierre Le Hors; courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

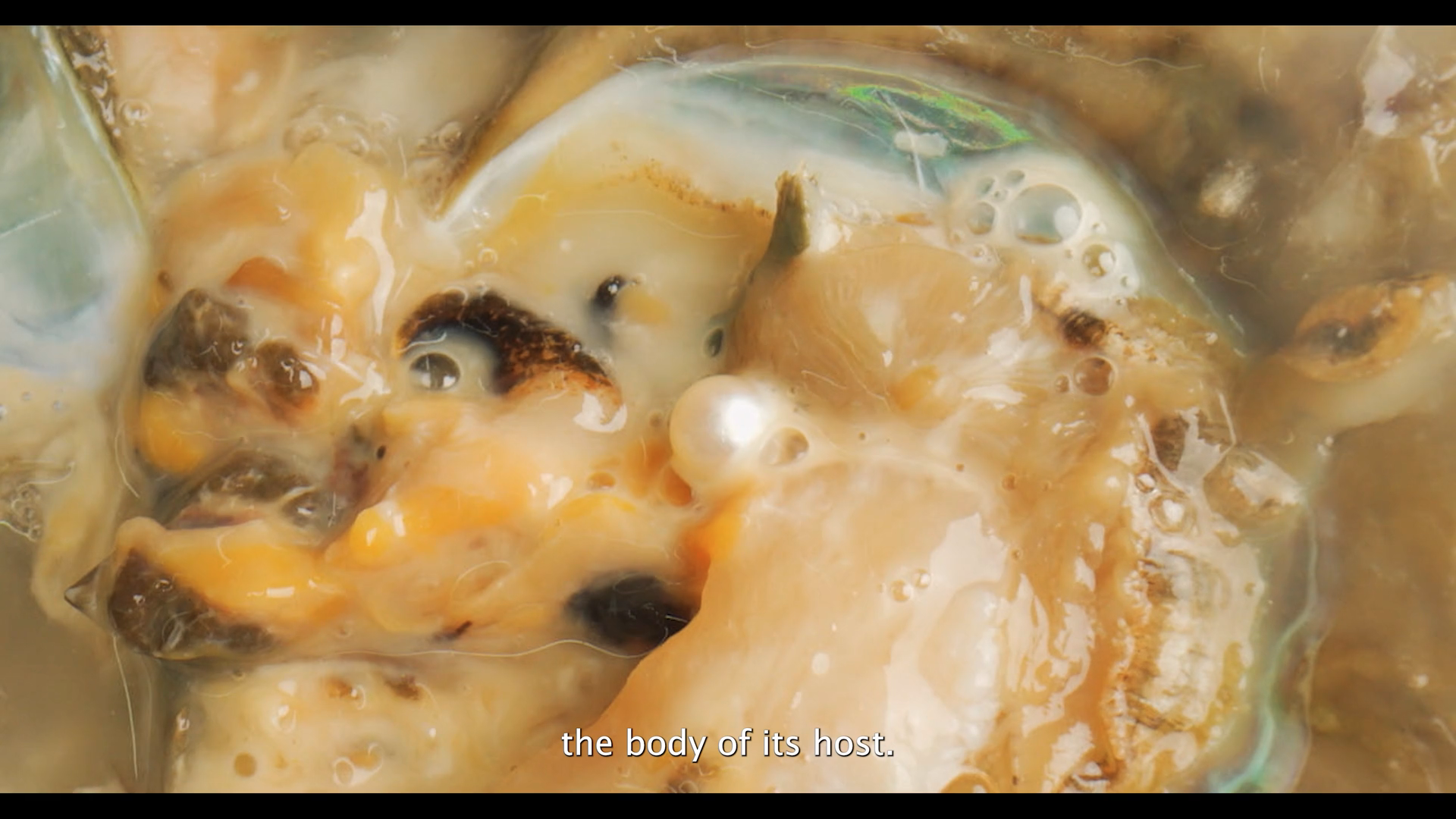

Palimpsest (2023), a single-channel video projected on the wall, introduces the ideas that infuse the show. This dreamlike study shows pearls being grown by implanting the mantle tissue of oysters native to Hong Kong with delicately cut Chinese characters for “pearl of the orient,” Hong Kong’s colonial nickname. As the sounds of shucking and the clicking of underwater life define an ambient, pared-down soundtrack, images take on the details of an oyster’s internal flesh, the waters in which they reside, a shell in hand. Through subtitles, we learn that oysters produce pearls in reaction to an intrusion, and thus in defense of their autonomy, and we are told of the artist’s desire for the oyster to swallow its own name to turn into itself. Words beginning with C are then listed—for example, “C is for colony,” which Hong Kong once was, and “C is for change,” what Hong Kong is experiencing now.

Jes Fan, Palimpsest (still), 2023 [ courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

Jes Fan, Palimpsest (still), 2023 [ courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

Palimpsest is also a visual index for the sculptures in the room. Pigmented resin sheets mimic the green swells of the city’s seascape, while glass orbs referencing the iridescent matter that oysters produce in response to an imposition are reflected in the mirrored surfaces of shopping malls, all of which Fan weaves into Palimpsest. The connections between meaning and context seem endless here. Take Oyster Bay, a shoreline on Lantau Island that was abundant with oysters but has been filled in with reclaimed sand for development alongside a vast swath of the sea. What metaphorical pearl might be produced from this incursion? What iridescence might grow as a result? If “C is you,” then who are we?

Tishan Hsu, screen-skins, installation view, 2023 [photo: Michael Yu; courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong.]

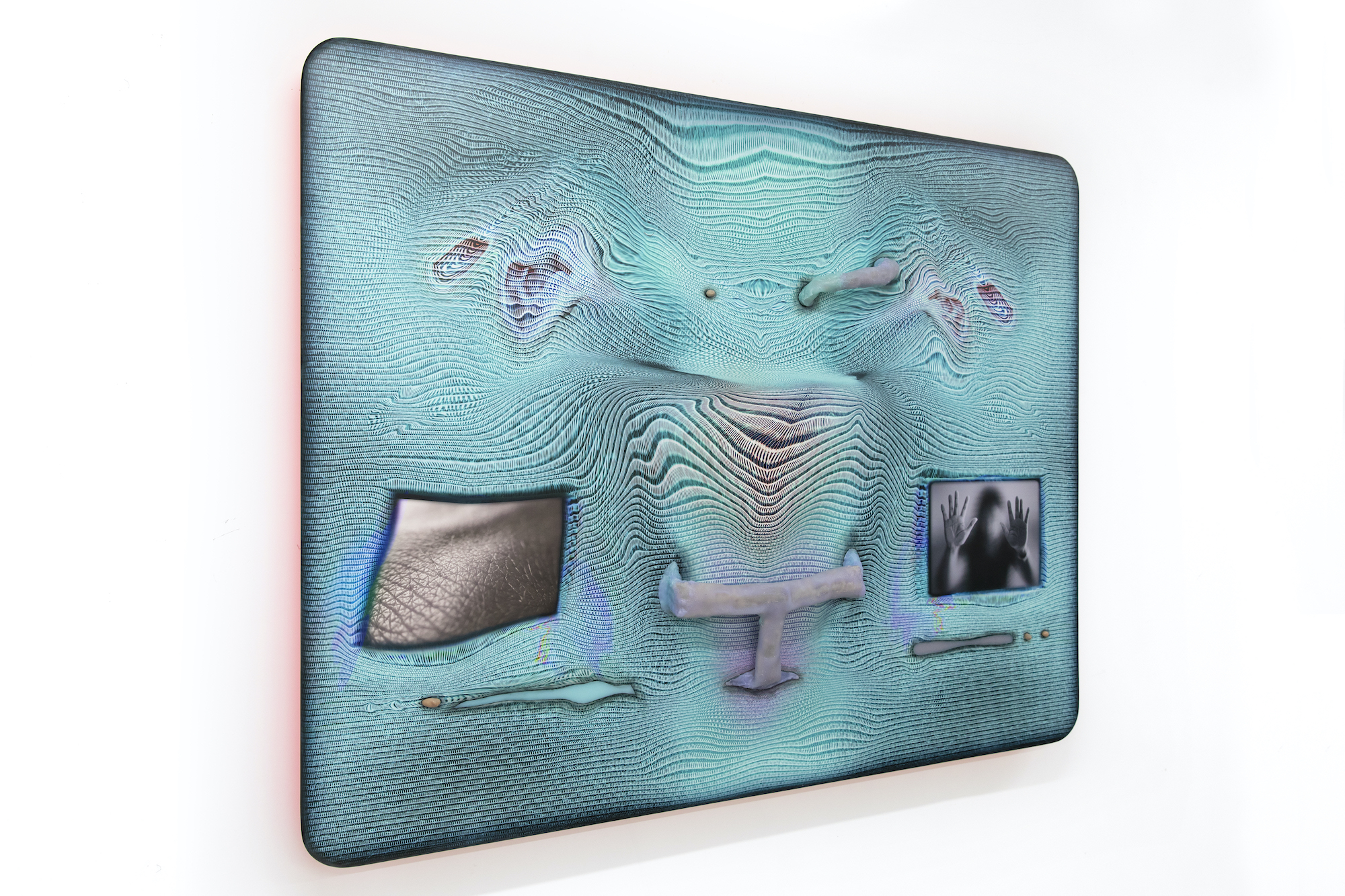

Questions such as these resonate across Hong Kong, like the murmuring rumble of an ever-populated present that holds bodies in uncanny tension—something Tishan Hsu seems to manifest one floor above in screen-skins. Works composed of wooden panels coated in UV-cured inkjet prints depict warped mesh fields, on which images are printed, like the black-and-white silhouette pressing its hands against a television screen in double-breath 1 (2023). Each composition is washed with undulating tones of pale fluorescent blue, corpulent pink, and sandy ocher. Silicone forms invoking bodily orifices create pustules and wounds across dermal surfaces.

Tishan Hsu, double-breath-1, 2023. UV cured inkjet, acrylic, silicone, ink on wood. [courtesy of the artist, Empty Gallery and Miguel Abreu Gallery. © Tishan Hsu/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York]

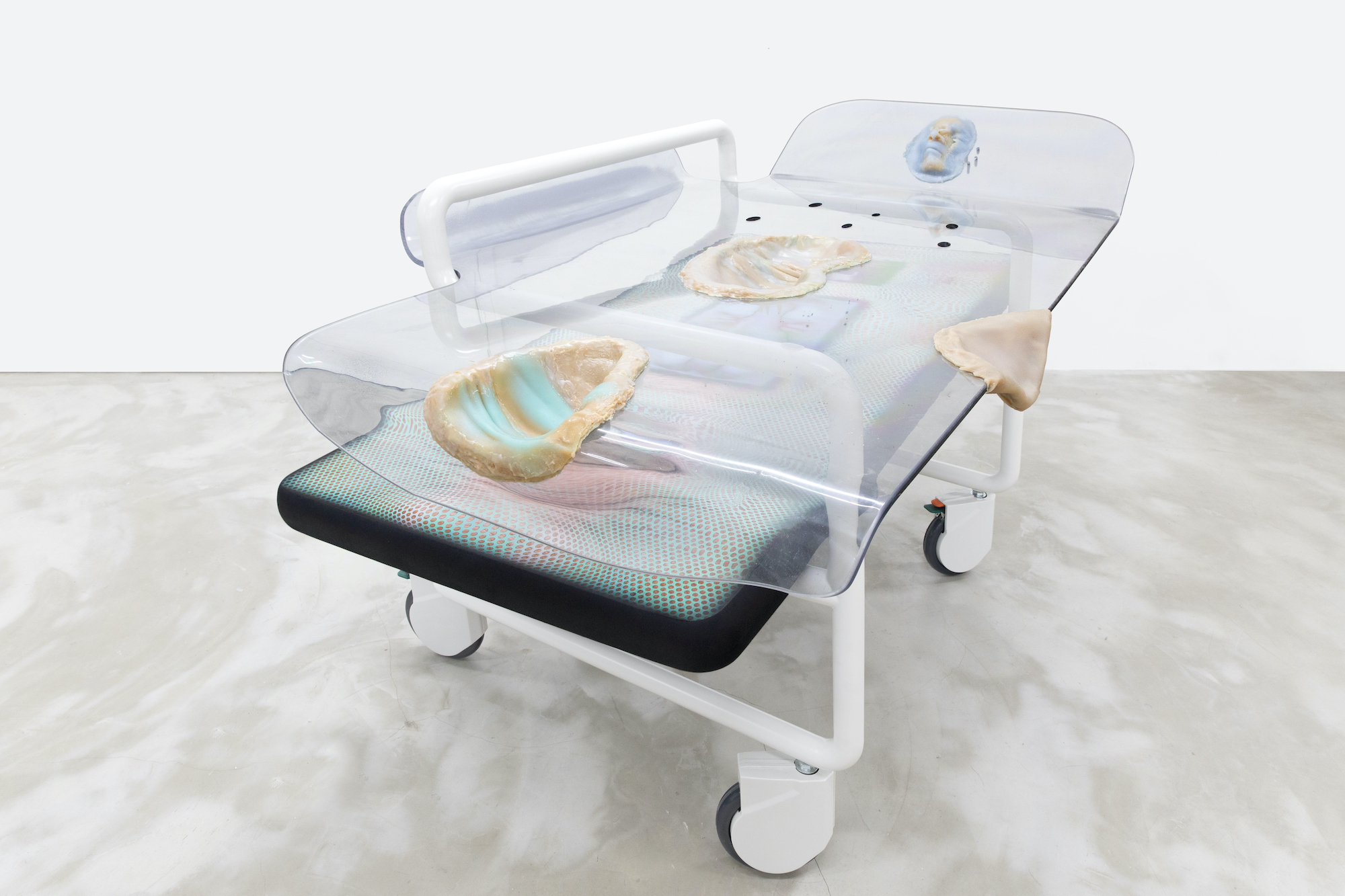

It’s all very Videodrome. That body horror manifests in phone-breath-bed 3 (2023), a sculpture presented in its own small room. A silicone face emerges out of a Perspex panel, where, lower down, a silicone slab forms a womblike concave depression. The panel hovers over the form of a hospital bed with the support of gray plastic piping, whose mattress is a screen-skin painting with creased dermal folds framing silicone protrusions that swell from the flatness. In its expression of a body that has become enmeshed with the technologies and apparatus designed to keep it alive, the sculpture harmonizes with the oyster shell traces burned into glass downstairs in Fan’s show—both expressions of a hybrid, post-human singularity.

Tishan Hsu, phone-breath-bed 3, 2023. polycarbonate, silicone, stainless steel wire cloth, UV cured inkjet, wood, steel. [courtesy of the artist, Empty Gallery and Miguel Abreu Gallery. © Tishan Hsu/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York]

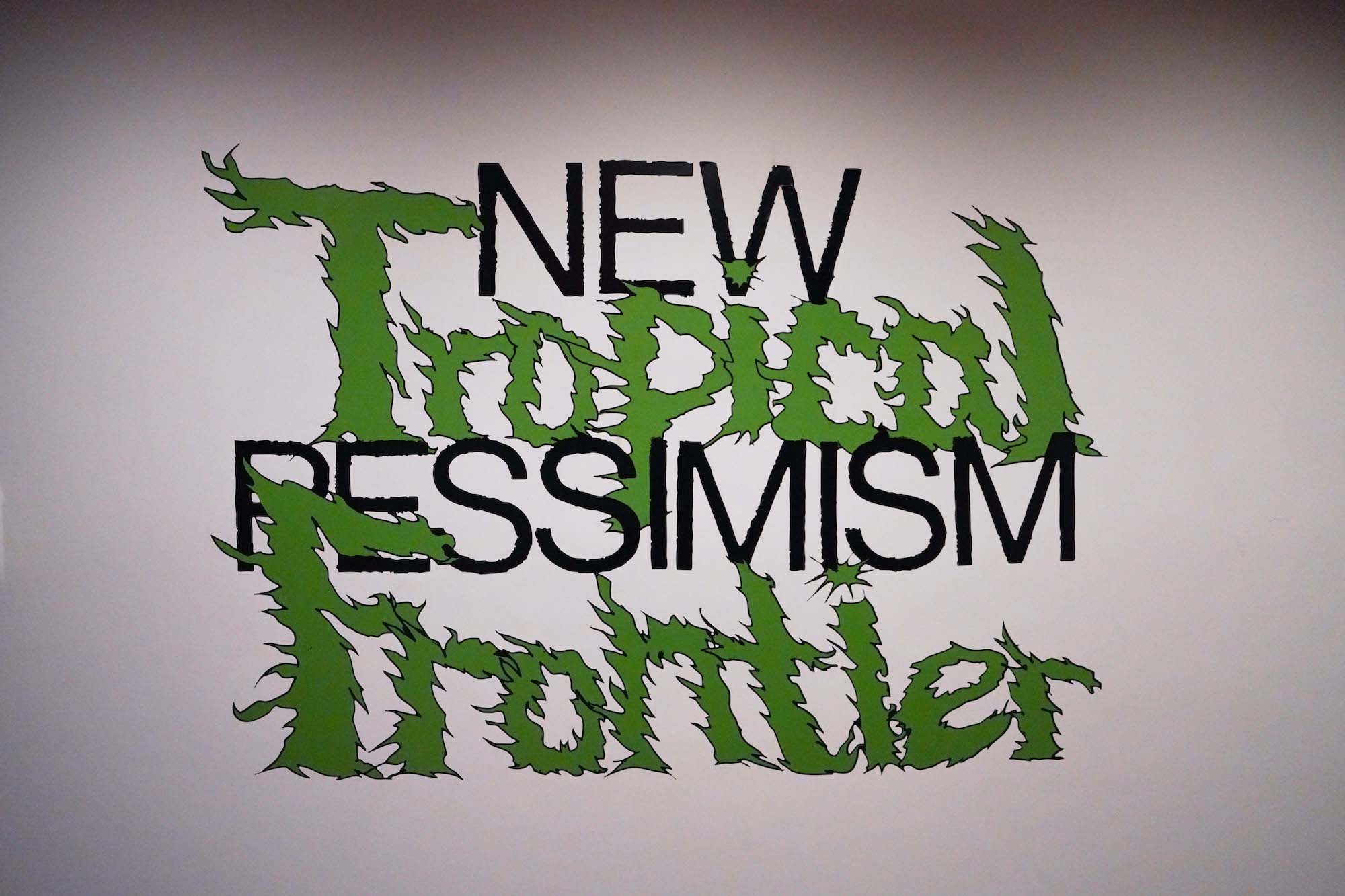

But while Fan’s exploration of nature is a metaphor for a mutational resilience—growths created from fragmented occupations produce something beautifully reflective—Hsu’s implosion of the body into the frames of technology visualizes a terrifying future. That unsettling spectrum was expanded in New Pessimism at Tomorrow Maybe, a show of works by Natasha Tontey and Riar Rizaldi, whose title inverted a slogan associated with Indonesia’s shift to liberalism in 1998—“new optimism”—evoked here to throw metaphorical fuel on the fire of the extractivist system of global industrial capitalism.

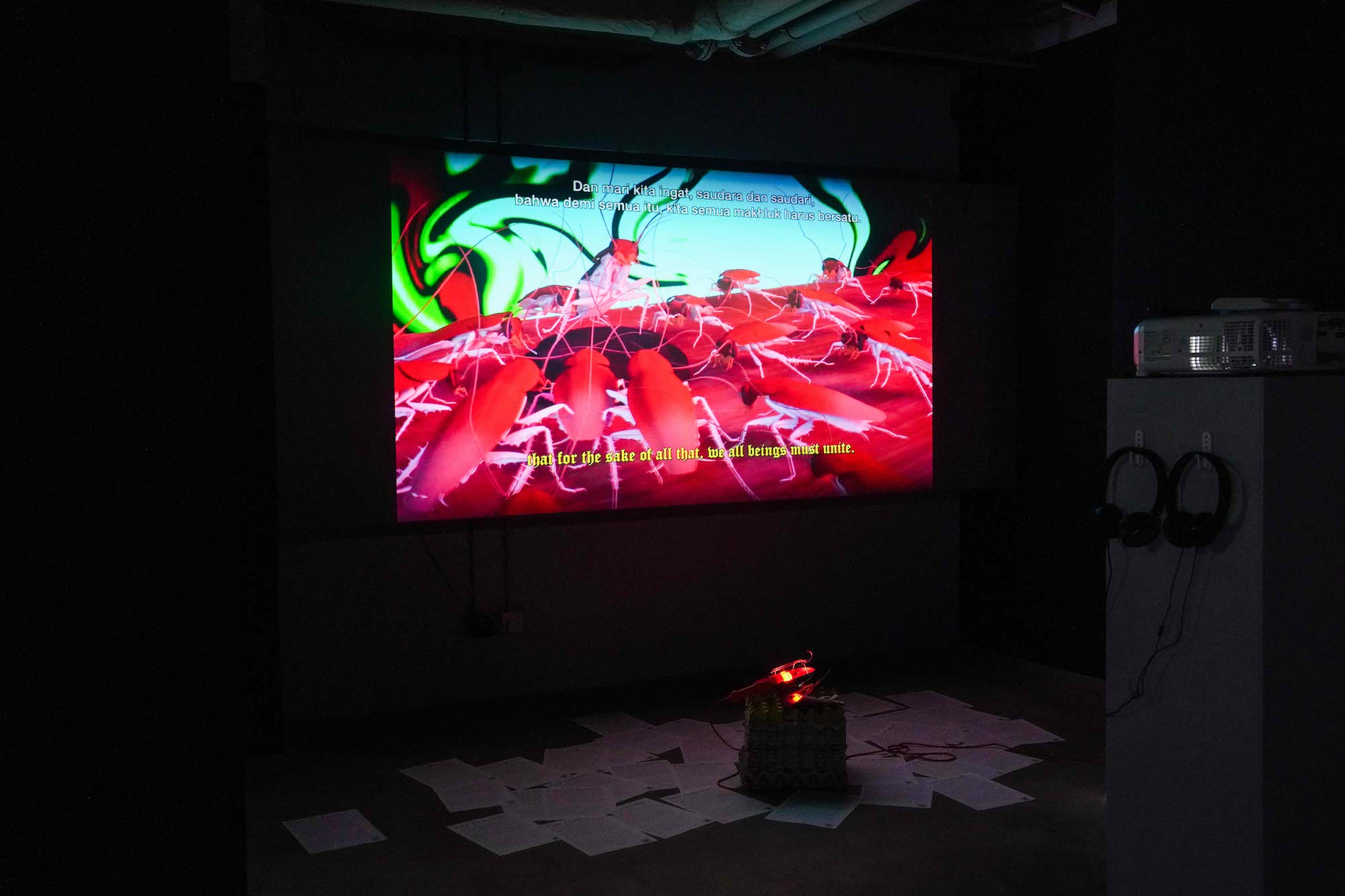

The exhibition began with Tontey’s Pest to Power (2019), an animation of cockroaches attending a conference inside a household cockroach trap. Inside, one roach delivers a speech railing against the treatment of nature. “We just want to live in the world that we were born [into],” says the leader, describing the tyranny of humans turning cockroaches into scapegoats for human malignancy, before calling for a pan-species movement for the betterment of Earth. Nearby, Otonomi Feral (2023), a single-channel film by Rizaldi, recounts a conversation with an anti-civilization ecoterrorist, who points out that “human evolution is not actually as developed as the evolution of ants or bees, which can organize in a more communitarian way.” It’s true, roaches have been proved to be just as communal, if not more so, which adds another dimension to the common description of protestors as “cockroaches” by politicians faced with popular uprisings.

Natasha Tontey, Pest to Power, 2019 [photo: Tze Long; courtesy of the artists, Eaton HK, and Tomorrow Maybe, Hong Kong]

With all that in mind, another single-channel film by Tontey offers a speculative view of how insects might see humans. The Order of Autophagia (2017–2021) shows three people, their faces painted like pantomime actors, who gorge on a feast of human limbs and organs. This ecstatic ritual feels like the terminus of capitalism, where the will to consume has reached its logical end—a cyclical nightmare of pure consumption that Rizaldi’s single-channel film Notes from Gog Magog (2022) distills by telling a pair of ghost stories anchored to two points in the network of capitalist production and circulation. Narrated over images of a shipyard in Jakarta is the story of a ghost—someone killed by a falling container. Meanwhile, photos of an empty office illustrate the story of a desk worker for Samsung in Seoul, who one night steps out of an elevator and into a “bizarre hell” visualized in the video by AI–generated imagery that merges corporate faces with demonic forms.

Riar Rizaldi, Notes from Gog Magog, 2022, duration: 19:32 [photo: Tze Long; courtesy of the artists, Eaton HK, and Tomorrow Maybe, Hong Kong]

Natasha Tontey and Riar Rizaldo, New Pessimism: Tropical, installation view, 2023 [photo: Tze Long; courtesy of the artists, Eaton HK, and Tomorrow Maybe, Hong Kong]

As images spiral across the screen, the worker describes hearing someone whisper in her ear, “Everything changes, Samsung remains.” Per the video’s credits, this quote apparently comes from a speech by Samsung’s president of research, a pioneer in brain-based AI work, whose vision for robotics resonates with the sculpture of a body collapsed into Perspex by Tishan Hsu in screen-skins. In that future, what might the roaches and oysters do?