Nope—A Certain Tendency of the Immaterial

Share:

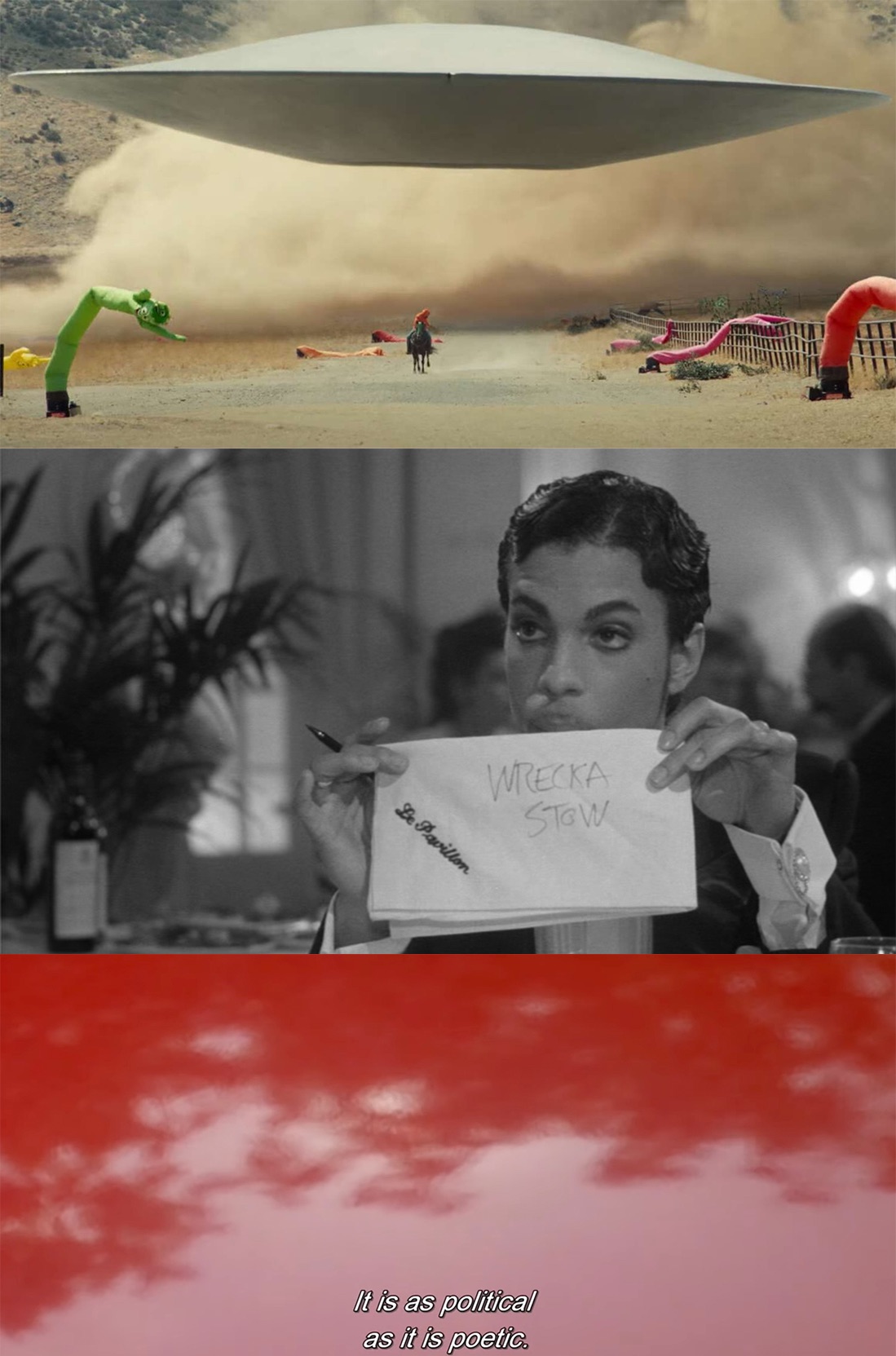

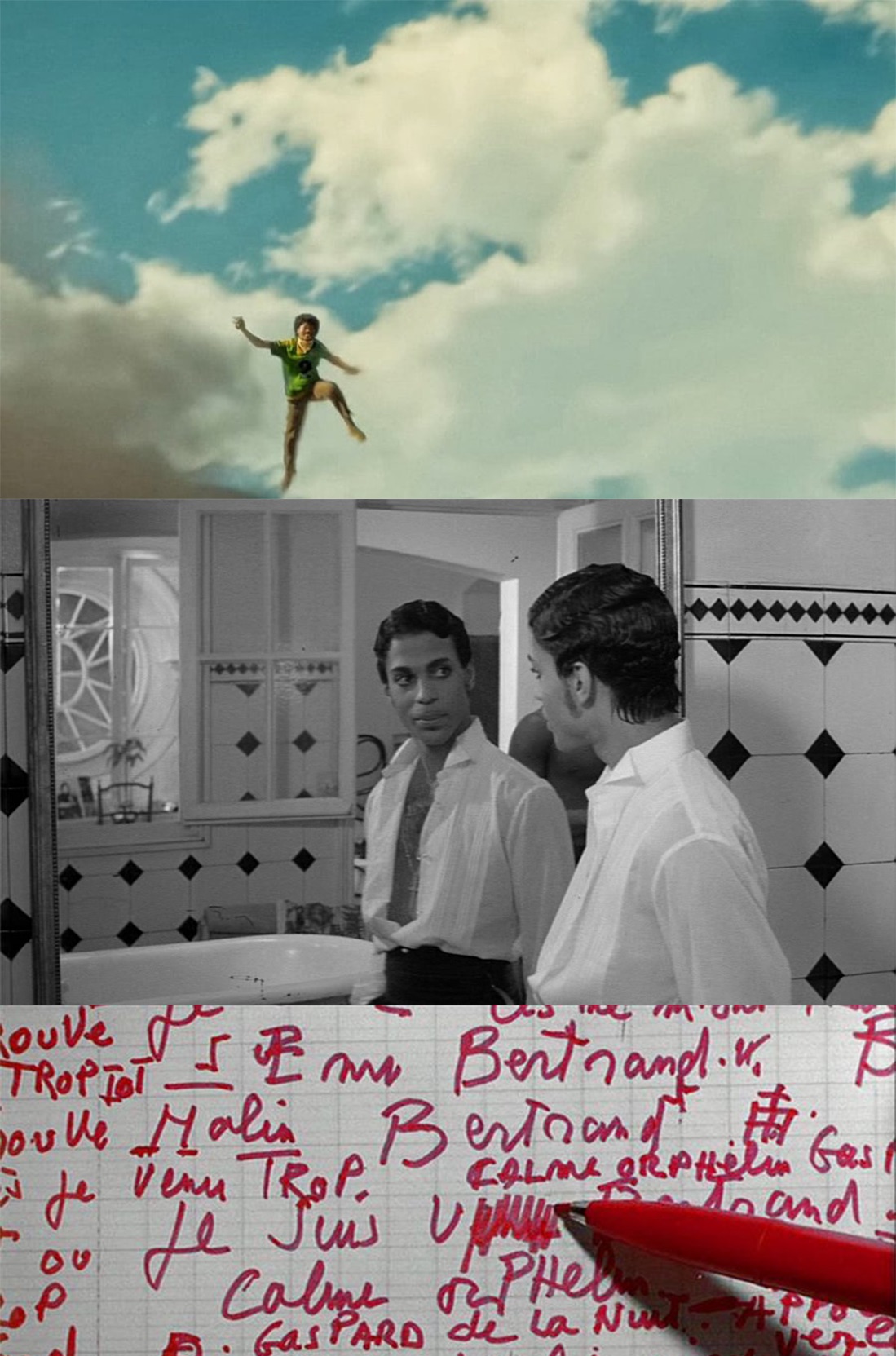

Top to Bottom: Jordan Peele, Nope, 2022, still [courtesy of IMDb and Universal Studios]; Prince, Under the Cherry Moon, 1986, still, [courtesy of IMDb and Warner Bros. Pictures]; Jean Luc Godard, Two or Three Things I Know About Her, 1967, still [courtesy of IMDb and Anouchka Films, Argos Films, Les Films Du Carrosse, Parc Film]

Whatever happened to that Black boy?

—Keke Palmer as Emerald Haywood

I.

I felt giddy coming out of Jordan Peele’s new movie. There were so many questions—I had so many questions. My experience of the work was such an internalized union of the sensorial. Of the visual—and the corporeal—taking hold of me. How to get—how to let you—in. I was freaking out. My mind volleyed from cribbing a line of dialogue of Roman Polanski’s—a lurid clunker spoken by Peter Coyote in Bitter Moon—“My nerve ends were jangling like bells”; to Yasiin Bey as Mos Def in Mr. Nigga, with his revelation that the carceral is just a dummy of the state, when he interpolated, “If I knew you were coming I’d have baked a cake.”

If I could only get this interiority on the page—sustain the moment. I wanted to talk directly to the filmmaker. To the viewer—the reader. Somehow give back to Peele—to Jordan—what he’d given me. A space of real freedom. A world opening in me. I thought it would help to talk out loud while writing—to hear what I was feeling. To have the text be on its feet, as it were, so that I could begin from the beginning. One moment the talking took form as a near monologue—less so outright performed but, rather, necessitated by a pre-forming. Do I begin with the image—with what I see—with what could be an image’s singularity? Nope speaks to a certain preoccupation with technology—possibly humanity’s undoing. But just as the film makes malleable space, the object, objecthood, temporality— compression happens, then a resuscitation through imagery. Or do I deal with the image as it’s dealing with me—singularly. Somehow, a recitation, inverting.

I was gonna start this with some Jacques Rancière thing on pensive imagery. And although I really did feel like an emancipated spectator while watching Nope the first, second, and sort-of-third screening, I’m going to ditch the images-that-think angle for something more vivid: organisms that dream. I learned how to emancipate myself from/through images and talk back to them as a child. Anything I watched, my grandmother was there alongside me, offering counternarratives that dispelled what I was seeing. There’s a lot of fuss being made about Jordan Peele’s latest work—some lauding, others re-nigging on this filmmaker’s vision. Let’s face it, he’s a visionary. There’s only one other moment in my life when I felt certain that entire worlds had opened in me—it was the first time I heard a Prince song. And then, infinitely thereafter, with each album, every music video, every concert, or image of him in magazines, in those movies. Prince always seemed to be challenging and channeling a poetics of contemporaneity.

I’ll tell ya what happened to that “Black boy.” Get Out was his Purple Rain record. Urgent. Gripping. Ahead of its time. Really out there, though everybody and they mama loved it. Us was Jordan’s Around the World in a Day record, just as beautiful, but darker. More coded. Lyrical in its opacity. Folks scratched their heads at it. Many couldn’t be bothered with it. Most admitted that they wanted a repeat of Get Out—Get In?—another Purple Rain record. Nope—Nope is Peele’s Sign O’ the Times record. What I mean is the scope. Ambitious. Breathtaking in its precision. So fully of the moment even as it looks toward something else—something closer to futurity. How the tactile can be inanimate. I WANT TO SAY, parenthetically, here: book, shirt, couch—or if I’m to interpret Nope’s unidentified alien—an animated bodiless thing. Out of the material, these Black men dreamed. That thing when “matter” resides in ambiguity. There’s a certain consciousness that Jordan’s movie has—the looking, the being looked at ways of looking, ways of being seen—that uses something as tacit as celluloid to investigate (pose questions/draw parallels/arrive at) certain things.

Eyeballing the “UFO” in Nope will get you killed. Meanwhile, our existence can be confirmed by “likes” on a screen. Under surveillance, the surveilled monitor how they’re being surveilled. Or—how, as technicians, as artists, as people, we can think about art. In the same way that we think about sex, or death, or loving—by getting lost in the movies. We can cop to it now, Guy Debord was right. But “spectacle” doesn’t have to be damning. It can be a living, breathing organism that hovers in the sky—our projection—that knows it’s a prop (a stand-in) for our collective anxieties. It can devour us. It can make props of us, too (look at us, re-enacting versions of ourselves every day). It can be the mechanism. Jordan’s marvel has an aperture—we’re the object. It’s a pretty deft camera obscura taking up American vernacular as its disguise, masquerading as a “flying saucer.” This genericizing of its own identity is a McCarthy-era bogey—a think piece on alienation. On spectacle. It’s an object, too—the film, I mean, knows how to be an art object. Materially elusive as praxis. Signifyin’ that straddles the line (but doesn’t draw it) between the material and the immaterial. The UFO turned “UAP” in the film’s story reminded me of any number of artworks by Christo and Jeanne-Claude—comments on materiality, on beauty. And sure, on the commodification of such things. Ideas, even. This extends to the air-powered “tube men” recontextualized in the film as, still, goofy hyper-commodified totems of good old-fashioned capitalism, still bait for an unsuspecting consumer, and, maybe still, much to Peter Minshall’s dismay at their recuperative staying power, overexposed and removed from Trinidadian Carnival. These are terribly important gestures.

So is “Run, OJ! Run!”—a brilliantly layered rigging that supports the whole movie, in the same way that Jean Jacket is, certainly (a little Black girl naming something out of the symbolic—marking). Let’s ascribe the redetermining of this organism, this object, as one’s own. More than naming: Black iconicity. These ideas ring true—deep cuts that are deeply coded. Just like Under the Cherry Moon before it. Both works being Black as fuck in their culturally specific familiarity. My friend Danny would call it Blackening.

As a viewer, I never once felt stranded. Jordan Peele doesn’t pander. He is a semiotician who understands that what that requires, is that he be a griot. The reverse is also true. Every griot is a semiotician. So, I’ve come to understand how this can flourish—how the Lovesexy and Jesus Lizard T-shirts give rise to the Buck and the Preacher poster hanging in the family’s living room: the Haywood’s finding home out West. I’ll never shake the image of Sydney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Ruby Dee, and the newly liberated in Buck and the Preacher, looking out onto a landscape virtually identical to Agua Dulce—not yet Compton or Watts or even The Valley. Different times, same stakes. Jordan Peele is not meandering here; his is a strong directive. I kept discovering gems in the family home—aesthetics wasn’t lost on me. The owl-themed string painting, for instance, made me think of David Lynch and my grandmother simultaneously—a surrealism that is Black kitsch. Black fandom. A mesmerizing of history. Minor objects as changelings.

And so, now, with regard to storytelling, can we get into Gordy’s racialized experience? The “Gordy” plot unfolds Rashomon style, partitioned, to account for its fractured perspective. You know, who’s doing the telling? There’s the familiarity of othering. I identified with Gordy—with Gordy’s presumed interior life—of feeling bludgeoned by the normative ruse of whiteness. Normativity comes in blows. Strangely, I also identified with the UFO/UAP/alien/living organism/flying saucer as “Jean Jacket,” and with Lucky—the horse that turns violent at the sight of his own reflection. What does that mean, exactly? That Homi K. Bhaba and W.E.B. DuBois were certainly onto something. But I think it also means that Emerald is me.

I wondered about the unseen, ever-present apparatus of the state that lurks throughout the film. We see its reach in Gordy’s subjugation, exploiting, and eventual murdering. Eerily, peripherally, the state is at the core of the dual nature of the unidentified flying object. The surveillance. The policing. Neither police nor government agents are afforded any screentime.[i] In Nope, the characters fend for themselves. That apparatus of the state is subverted, or at least made diminutive, in the conceit of the Kid Sheriff TV show—in the notion that it’s enough to just hear the cops (on Gordy’s set, at Jupiter’s Claim in the finale, via sirens off screen) to convey a sense of menace, of capitulation. The only sheriff that saves the day here is the inflatable one that the “alien” (transposed as Jean Jacket) swallows in a gorgeously balletic scene. The fraying of the organism’s body reveals its true self—delicate fabric trussed to an oculus—which billows, not flies. It’s astonishing. It’s almost phantom-like. Made of chiffon or silk or cupro—the last of which would make the most sense for its minimal footprint as a biodegradable material. More of what Jordan’s up to—not just, look at this thing! At Sarah Lawrence, Jordan Peele studied puppetry. Puppetry! He knows quite intimately how to embed thought, action, feeling into things.

[i] I DO think that Wes Anderson is reorienting the state, too. The prevalence of law enforcement in The French Dispatch doesn’t feel uncritical to me—they’re Keystone Cops. Maybe more importantly, there’s a heightened sense that they’re wearing costumes. It is a Wes Anderson flick, after all.

Top to Bottom: Jordan Peele, Nope, 2022, still [courtesy of iMDb and Universal Studios]; Prince, Under the Cherry Moon, 1986, still, [courtesy of IMDb and Warner Bros. Pictures]; Jean Luc Godard, Two or Three Things I Know About Her, 1967, still [courtesy of iMDb and Anouchka Films, Argos Films, Les Films Du Carrosse, Parc Film]

This nigga …

— Keke Palmer as Emerald Haywood

II.

What are we talking about here? The indiscernible? The film makes no overt spiritual claims—except to the cinematic. Putting the living organism in drag as a flying saucer, Jordan reaches deep into the pocket of the horror genre to suggest the UFO has seen The Amityville Horror—it excretes the blood and belongings of its previous victims all over the Haywood home. I really want to get more into his commentary on material culture and visuality. That shit makes me wanna sing. Sometimes, the alien looks like a rear projection—aerially—flung on a string. Not camp, but here, reveling in objecthood, in speculative feats of whimsy. Terror, even, and terror never feels unwieldy. The cyborgian paparazzo on a motorcycle reads as an artifact—and is treated as such in the film. Sounding like a parrot or gimmick while he pleads for the shot. In spoofy contrast to the auteur cinematographer who martyrs himself to get the impossible shot from inside the thing that sees. A scene of the character, Angel, changing film reels inside a film-changing tent is less fetishistic than it seems. The gesture is unadorned. Many viewers might be thinking, what is that thing? Some doubling. Otis Haywood Jr. evokes Black Dada Nihilismus when staring down the “alien being,” as if to say, Pull up! Or, when shown in profile, shrouded in mystery, framed as “out yonder”—me cueing the Tramaine Hawkins refrain “Goin’ up yonder,” just as Jordan knew I would, in my head, to this scene.

Where am I goin’? I thought about ending with Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life, nominally undone in the film’s observations on the routine monetizing of the poetic. I’ve been pelted with filth, made a fool of, and regarded contemptuously. Let me be propelled by myth. Let myth be the thing that propels me.

Sherae Rimpsey is an artist and writer. Rimpsey is the Mildred Thompson Art Writing and Editorial Fellow.

The Mildred Thompson Arts Writing and Editorial Fellowship is a collaboration between Art Papers and Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University. Funding for the two-year editorial position was provided to Newcomb Art Museum by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for an emerging Black arts writer/editor to gain hands-on experience as part of Art Papers’ editorial team. The fellowship also honors and builds upon the legacy of Mildred Thompson, associate editor of ART PAPERS from 1989 to 1997.

Conceptualized as part of Art Papers’ Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility efforts, the fellowship received seed funding from AEC Trust and The Homestead Foundation to pilot the program in 2022.