Muhammad Ali: No way to hide

Muhammad Ali, No way to hide, installation view, 2023 [courtesy of the artist and AllArtNow, Algiers]

Share:

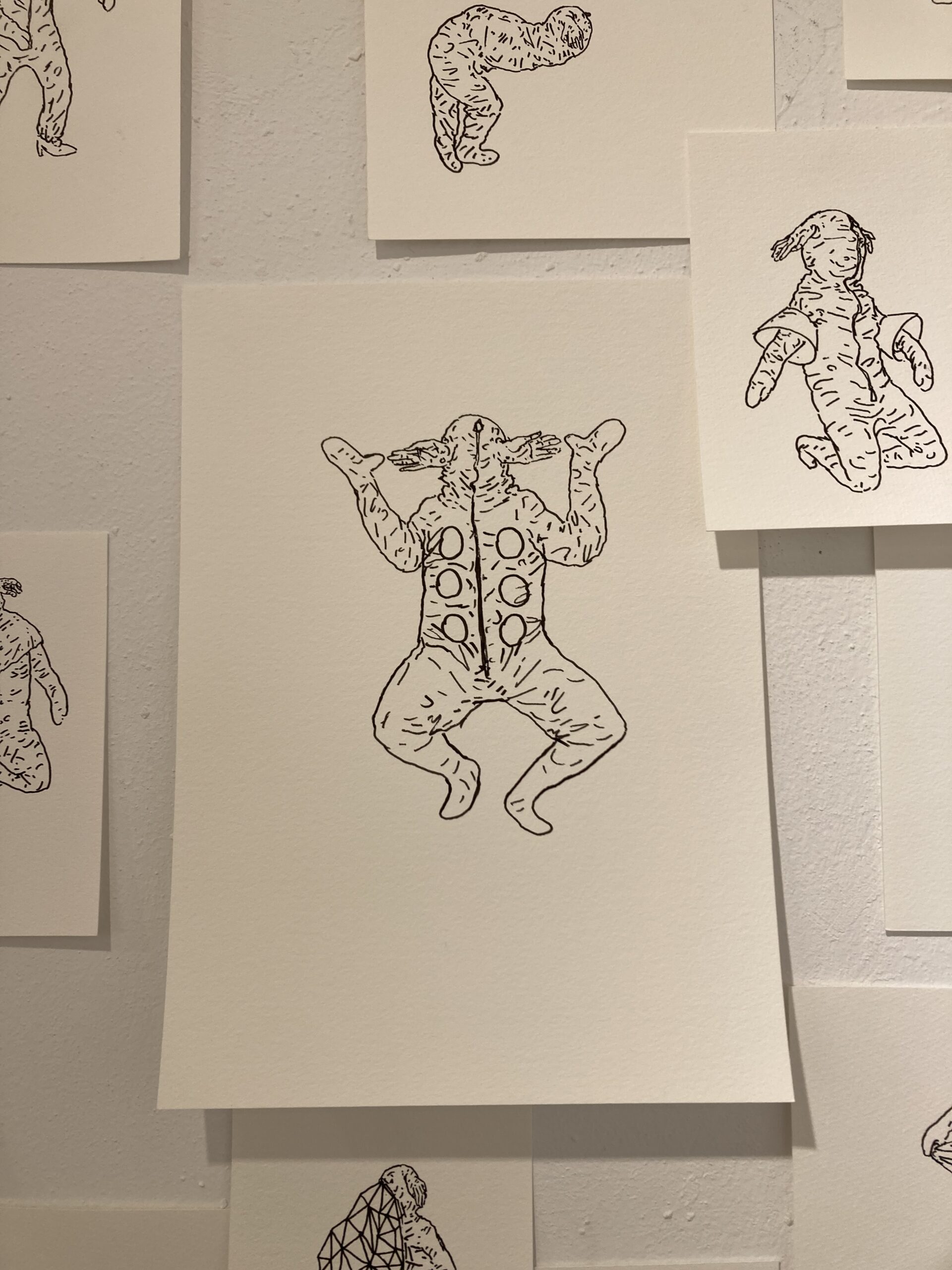

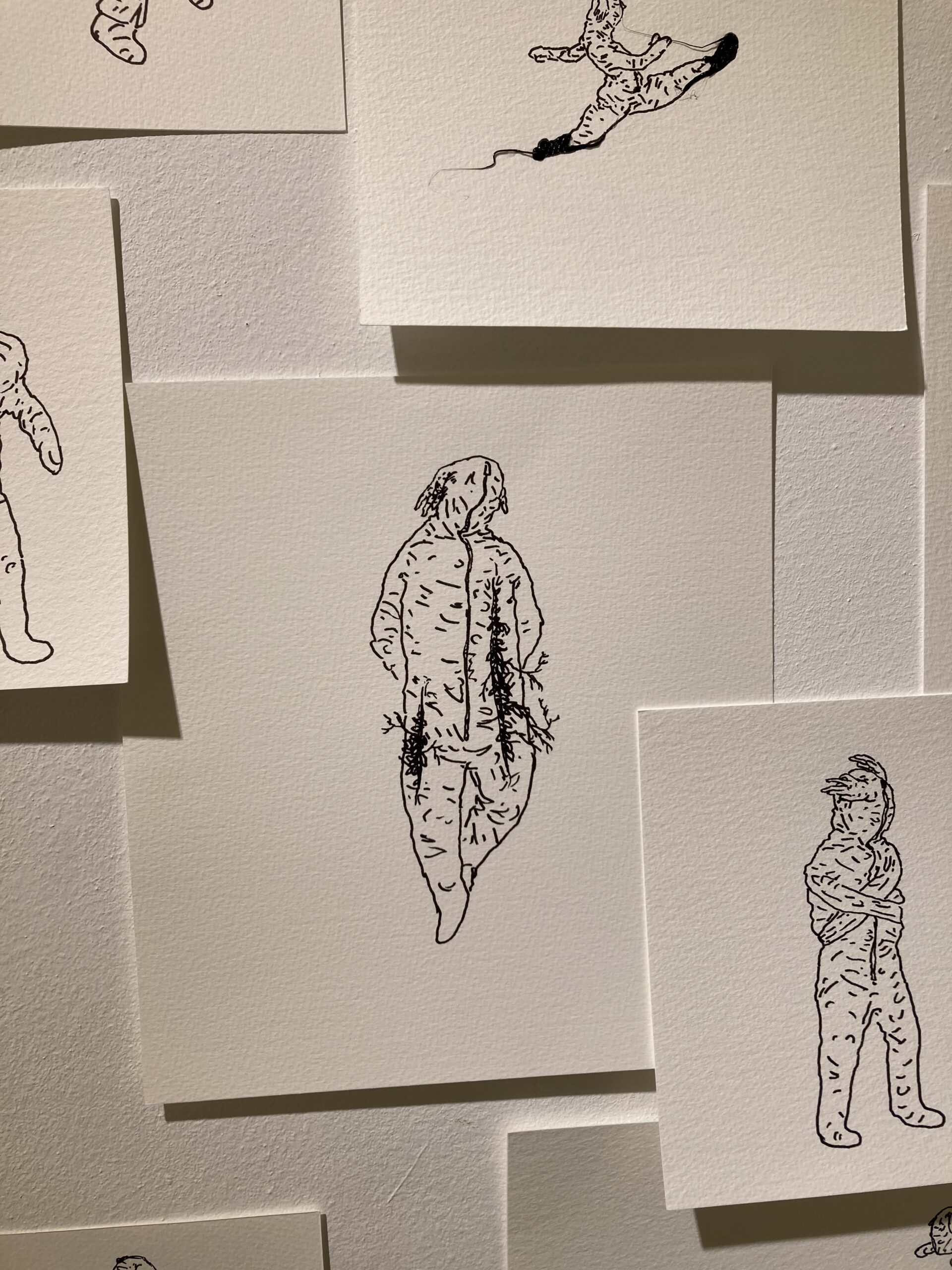

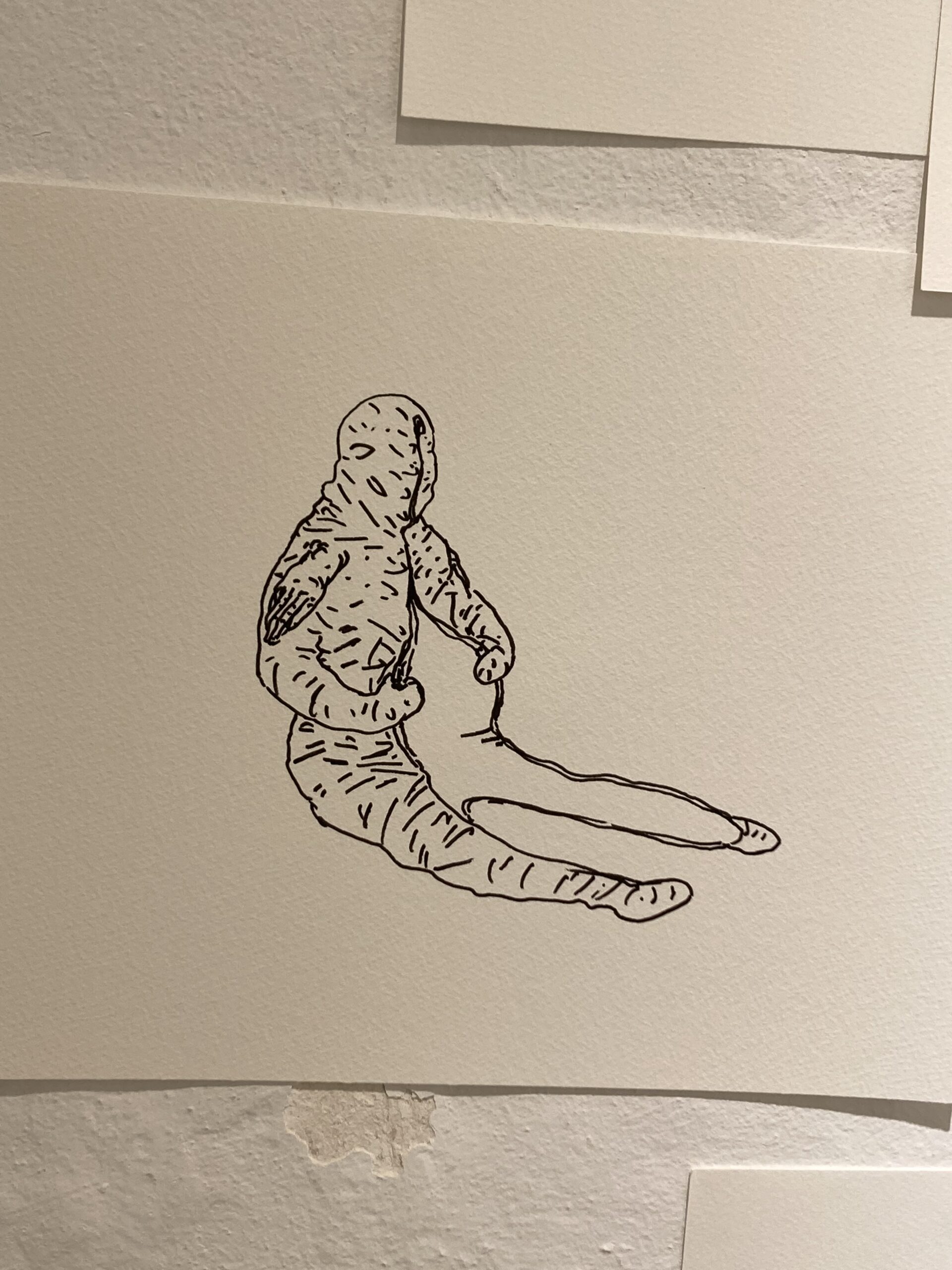

A single figure dominates the works in No way to hide, Muhammad Ali’s solo exhibition at the Dar Abdelatif in Algiers. The figure is named AEIOU—a list of all the Latin alphabet’s vowels, which connect consonants and allow words to be speakable. In many drawings in the exhibition’s first room, AEIOU is dressed in a coverall garment that extends over every inch of his body, even zipping over his face. On either side of his head, where one might expect to find ears, two hands sprout from the coverall like sentient tassels. AEIOU is drawn in motion: leaping, with arms outstretched, over an unseen hurdle; bending to one side and gesturing broadly for an unseen other to pass by; staggering, with one arm bent to rest a hand on his lower back in a way that suggests both exhaustion and pain; and balancing gracefully on one knee, the other leg outstretched in the manner of a child who is ambivalent about standing. Although the gestures themselves are ordinary, taken together, the drawings illustrate an endless variety of efforts required to accomplish something abstract.

Muhammad Ali, No way to hide, installation detail, 2023 [photo: Natasha Marie Llorens; courtesy of the artist and AllArtNow, Algiers]

Muhammad Ali, No way to hide, installation detail, 2023 [photo: Natasha Marie Llorens; courtesy of the artist and AllArtNow, Algiers]

Abstraction, in Ali’s work, is tinged with existential futility. This impression is created, in part, by the inclusion of such works as one in which the figure is seated, his coveralls unzipped to the ankles. AEIOU holds the suit open to reveal to himself that the garment is empty, and that his own body does not exist. In another image, the figure is doubled over while the material of his coverall—which here has the texture of chewing gum—is aspirated into some void just beyond the drawing’s frame. The forces opposing AEIOU and the boundaries of his universe are left unarticulated. Without horizon or grounding, anything can happen to him.

According to Ali—a Syrian-born, Stockholm-based artist who was educated first at Damascus University and then at Konstfack in Stockholm—the figure is based loosely upon Alfred Jarry’s notion of ‘Pataphysics. ‘Pataphysics is an absurdist philosophy developed in the early years of the 20th century, and which later fascinated such artists as Marcel Duchamp and Picasso, then surfaced in reference to the SituationistInternational, and to John Cage at Black Mountain College. It is a theory of the absurd and, therefore, difficult to summarize, but one of its more concrete propositions is that is the space between the thumb and forefinger is divine—the location of God—a fact that renders hand gestures particularly significant from an existential perspective. The philosophy emphasizes a phenomenonal idea of reality—things occur in unique and inexpressibly complex moments—and contrasts with the scientific approach to reality that tracks the repetition of events to draw conclusions about truth from the fact that events reoccur.

Muhammad Ali, No way to hide, installation detail, 2023 [photo: Natasha Marie Llorens; courtesy of the artist and AllArtNow, Algiers]

Muhammad Ali, No way to hide, installation view, 2023 [photo: Natasha Marie Llorens; courtesy of the artist and AllArtNow, Algiers]

No way to hide installed across three narrow chambers, and only the first room is decorated with Ali’s unframed ink drawings. In the second, an animation is projected against the back wall. In the animation, AEIOU lies motionless within an altered photograph of the living room in the Algiers apartment where the artist was in residence to prepare this exhibition. The furniture, the rugs, and all traces of everyday life have been removed, leaving only the walls and the ornate molded-plaster ceiling. In the animation, black liquid drips from the ceiling’s centerpiece medallion into an open cavity in AEIOU’s abdomen.

Ali digitally mapped the third and final chamber to make a virtual landscape scaled to the room’s dimensions. The landscape was accessible via VR headset. Inside the virtual space, Ali placed a collection of monumental heads drawn freehand along the edges of the space. Viewers were invited to grasp these virtual objects by using their actual fingers, “pick them up,” and move them about. If a virtual object was brought close to a viewer’s ear, a faint soundtrack of street life in Algiers would become audible. Each object bore a different soundtrack, a different moment of the day on the street. Thus, the medium of drawing expands in each room, but with each expansion it draws closer to a specific site—a room in Algiers, a street in Algiers—and to the dimensions of the exhibition space itself. As Ali moves further from his medium in a classic sense, he draws more concrete conclusions about the relationship between the figure and the environment it inhabits.

I read this specificity as Ali’s response to the striking visual environment of Algiers. The city is built on terraces carved from steep slopes that overlook the enormous Bay of Algiers. Ali was in residence at the center of the colonial-era city, in a Haussmannian neighborhood, built with stubborn rectangularity notwithstanding the topographical impossibility of broad avenues or straight promenades.1 The Dar Abdelatif, by contrast, was built in the second decade of the 18th century by dignitaries from the Ottoman regency in Algiers. First a diplomatic residence, then a military plague ward, then a permanent exhibition space for colonial agricultural products, the villa was transformed in 1907 into a residence for artists. In the 20th century, the building served a similar role to that of the Villa Medici, a building used by the French Academy in Rome since the beginning of the 19th century to house visiting artists. From 1907 to 1961, the Villa welcomed laureates of the Abd-el-Tif prize, which was also modeled on a conversion, and funded a year’s stay in Algiers. The award was given by the society of French Orientalist Painters to a list of artists consisting almost exclusively of Frenchmen.

Today the Dar Abdelatif—tucked away along the winding road from the Jardin d’Essai to the Martyrs’ Memorial—is home to an organization (Agence algérienne pour lerayonnement culturel, or AARC) that supports Algerian cultural activities. Its white, molded-plaster walls and bright-turquoise wooden doors represent a state-sponsored return to the vague authenticity of Ottoman rule and support for a generalized amnesia about the uses to which Orientalism was put by the colonial regime. In this kind of mythologized space, it’s a relief to encounter Ali’s darkly absurdist animation of viscous liquid seeping through an ornate architectural feature.

Natasha Marie Llorens is a Franco-American independent curator and writer based in Stockholm, where she is a professor of art and theory at the Royal Institute of Art. Llorens regularly contributes art criticism to e-flux agenda, and she has recently published with Artforum, frieze, CURA., Contemporary Art Stavanger, and La belle revue, among others. She holds a PhD in modern art history and comparative literature from Columbia University and an MA from the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College. She is currently at work on a book project about five experimental films from the 1960s/1970s in Algeria and collaborating on a research project about Algerian socialism with contemporary artist Massinissa Selmani. The first exhibition associated with this research is to open in Algiers in May 2023.

References

| ↑1 | The exhibition was the conclusion of Ali’s three-week residency in Algiers, made possible through the collaboration between a Swedish arts institution founded by Syrian artist Nisrine Boukhari and Syrian-born curator Abir Boukhari, AllArtNow, and an Algierian artist-run space, the Box24, founded by Walid Aïdoud and Sofiane Zouggar. The project was funded by a Swedish state-run organization, Konstnarsnamnden, but the Dar Abdelatif was instrumental in producing the exhibition. The intricacy of this collaboration reveals some of the effort required to invent infrastructure for international artistic exchange in Algeria. The Dar Abdelatif was built around 1715 by the Ottoman ruling class as a residence. The builkding was requisitioned by the French colonial army shortly after its invasion of the capital city in 1830. The army used the villa for a few years as an infirmary, after which time it was rented to the agricultural company associated with the nearby botanical gardens, the Jardin d’Essai, for more than half a century. It was restored to its early 20th-century state in 2008 and is now classed as a national heritage site. |

|---|