Motoko Fukuyama, La Bohéme, installation view, 2018 [courtesy of the artist and Tops Gallery]

Motoko Fukuyama / Virginia Overton

Share:

“As a child, I thought slugs were snails that ran away from home. I would force slugs into the empty shells of dead snails to give them a home ….” The subtitled voiceover that begins Brooklyn-based artist Motoko Fukuyama’s video La Bohème (2018) is taken from Iede No Susume (roughly, An Encouragement to Runaways), a 1972 essay by postwar, avant-garde dramatist Shūji Terayama (1935–1983). Meditations on home, entropy, dislocation, and the distinct melancholias that accompany people who run away as well as people who stay behind unspool over the duration of Fukuyama’s 20-minute free-form documentary, which provided the focal point and title of her recent exhibition at Tops Gallery in Memphis, TN (January 26–March 10, 2018). Additional sculptures and silkscreen prints adorned both locations of gallerist and Memphis native Matt Ducklo’s laudably inventive exhibition space. One occupies the windows of a sealed storefront gallery downtown, the other the basement of a commercial printer’s building in the arts district, around the corner from where Fukuyama studied: the soon-to-close Memphis College of Art.

Fukuyama is one of two Brooklyn artists with roots in Memphis who returned to the city to open concurrent shows early this year. Tennessee-born sculptor Virginia Overton returned to her alma mater, The University of Memphis, for a show at the university’s Fogelman galleries (January 20–March 9, 2018). Overton, known for her large-scale site-specific installations and Home Depot hardware readymades, typically forages for materials locally, responding to the particular architecture of a given site with repurposed objects found in the immediate environs. This show was presented in two parts, one gallery containing six new sculptures (some wall-hung, some free-standing), sourced from salvaged wooden window frames and other materials found in her former advisor Greely Myatt’s studio, and another a room-sized installation of electrical wiring, flowing water, and overturned pedestals from the gallery’s storage room. The installation, titled Untitled (Water Feature for Gallery B) (2018), was comical from the outset thanks to the sheer brazenness of its execution, which is typical of Overton’s tendency to utilize objects in ways other than those for which they were intended. Live wires snaked across the walls like elaborate line drawings; these connected precariously to water fountains housed in plastic-lined MDF pedestals that were obviously never meant to hold liquid. There’s a sense of danger, a performative hyperbole somewhere near the heart of Overton’s work, as well as a curious probing at the origins of materials and the boundaries of their use.

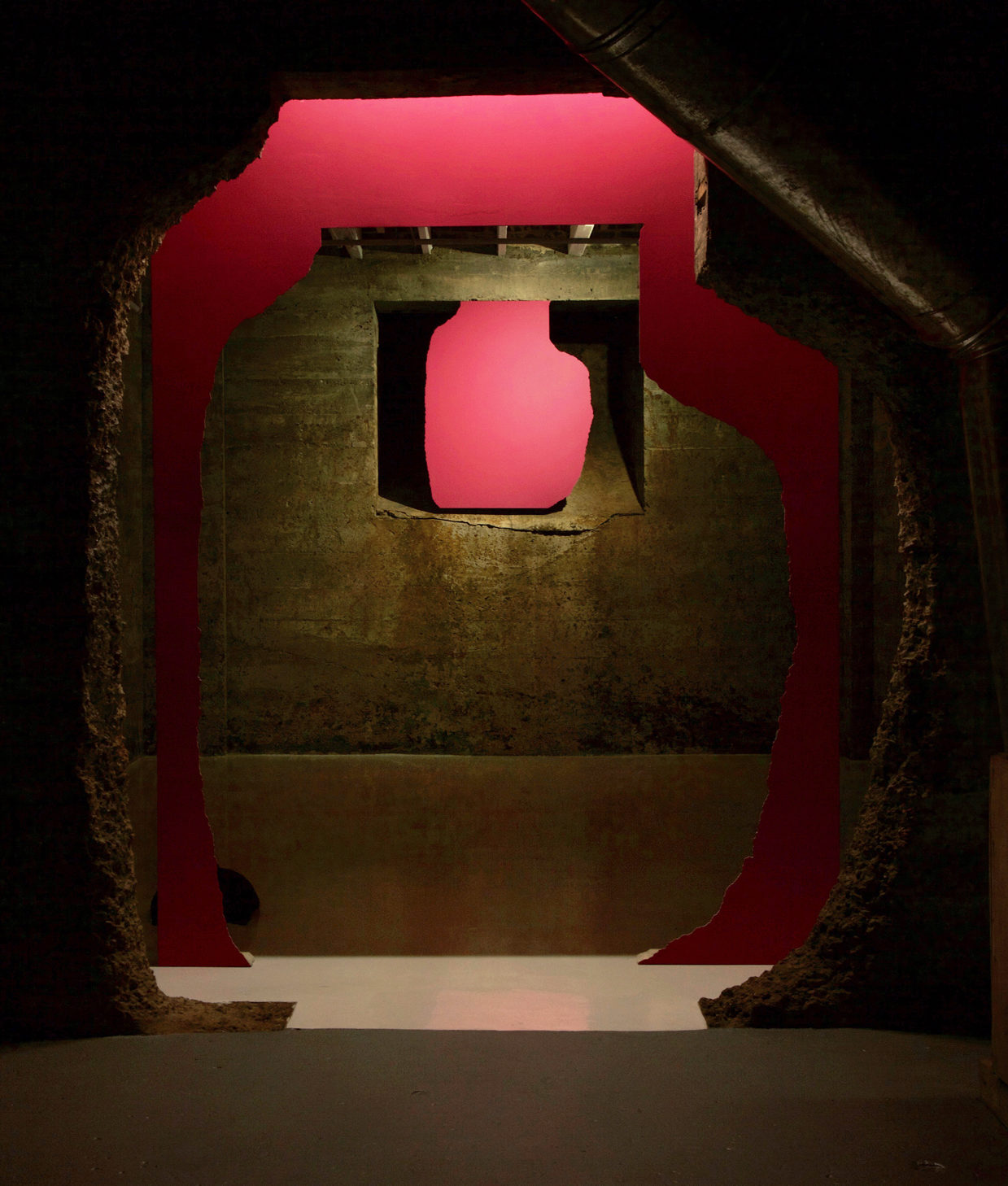

Motoko Fukuyama, Ancient & Forward Fuchsia, 2018 [courtesy of the artist and Tops Gallery]

In the past, Overton has made pointed use of object-signifiers of Southern culture, such as pickup trucks, weather vanes, and mud flap girls. Her general approach to materials evokes a DIY ingenuity—“git-’er-done” making do—that similarly gestures toward her rural roots. Overton hadn’t exhibited on campus since her MFA thesis show at U of M’s art museum, which consisted of a single sculpture titled In the Making (2005): a 1957 John Deere tractor procured from her father’s farm and suspended from the ceiling by Overton’s signature ratchet straps, levitating the machine just above the floor.

In a similar investigation of family, Fukuyama’s La Bohème is a portrait of her older sister Naoko, who introduced the artist to Western pop culture yet remained behind in Japan as her sibling ventured abroad. In the long interview that structures the film, Naoko recalls the workaholism that typified her late 20’s as a Tokyo graphic designer, culminating in a nervous breakdown. “Eventually, I had out-of-body experiences,” she says of her condition,” when I was at work, typing, I couldn’t tell who was moving my fingers […].” Naoko narrates a cascade of ensuing psychological diagnoses, including autonomic disorder, depression, bipolar disorder, and PTSD. She spends years at a time unable to work, housebound and lost in the past. She describes her state as being stuck in a permanent adolescence, unable to connect with the present, but consumed by the obsessions of her younger self. Naoko fits the archetype of the otaku—a social group that has been recognized in Japan since the 1980s, but whose characteristics now uncannily describe aspects of 21st-century American youth culture. Obsessed with manga, anime, and cosplay, she withdraws from the world into fantasy, losing the ability and desire to connect with society at large. Naoko’s object of fixation is a 40-year-old-and-counting graphic novel called Crest of the Royal Family, which tells the story of an American teenager who is transported across time to ancient Egypt and falls in love with a handsome young Pharaoh, coincidentally named Memphis. Scored by the New York experimental musician Chuck Bettis, the video climaxes as Naoko fully immerse herself into her fantasy world, as Fukuyama’s camera captures the skill, wit, and creativity that her sister pours into her home-made costume design, set painting, and role-play performance. The result is an uplifting burlesque and melodramatic camp in the spirit of early Jack Smith—and an earnest anthem to the healing powers of creative work.

Uniting these shows was both a sense of play and a grappling with the past. Overton and Fukuyama had previously collaborated on a 2013 video titled Storyteller, which documents the felling and milling of an Eastern red cedar tree in Lebanon, TN. The finished wood eventually paneled a wall of Mitchell-Innes & Nash gallery in New York for Overton’s solo show that year. The artists certainly have adjoined interests—Overton in the way things are made, Fukuyama in the people who make things. Their concurrent shows in Memphis offer concentrated, rewarding excursions into both.