Morehshin Allahyari: A Jinn Rather than a Cyborg

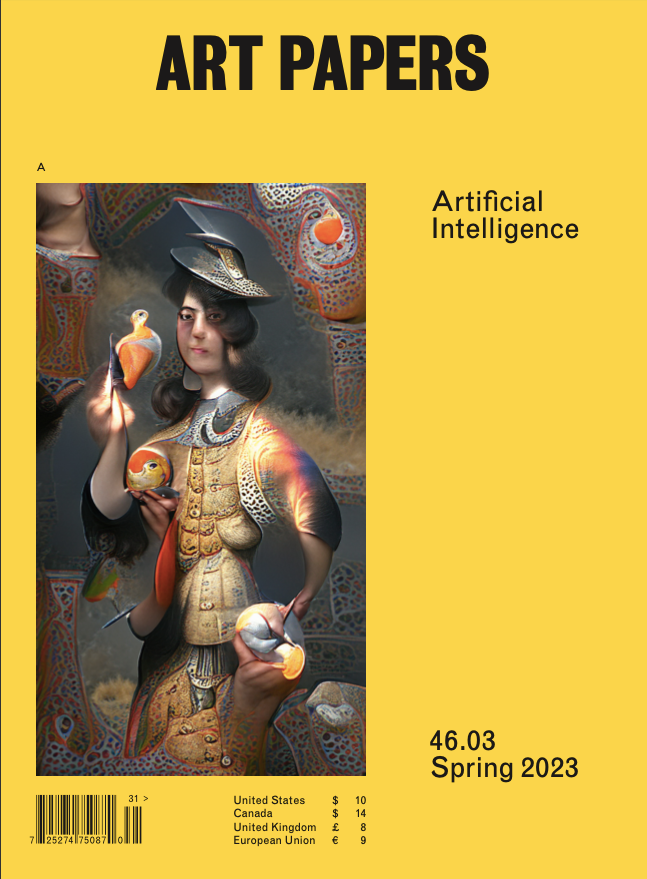

Morehshin Allahyari, Moon–faced ماه طلعت, installation view, 2022 [photo: Pinelopi Gerasimou; courtesy of the artist and the Onassis Stegi]

Share:

An oddity of much recent algorithmically generated art is that, while it traffics in the rhetoric of hyper-novelty, it often relies on datasets derived from 500 years of the Western art–historical canon. In effect, the newly made work inherits the timeworn coloniality of Western art history, and that of artificial intelligence as a field.

Morehshin Allahyari—a New York–based, Iranian Kurdish artist, activist, and educator—attunes us to markedly different algorithmically generated visions. In her decade-spanning corpus, Allahyari has addressed the intertwining forces of digital colonialism and European visual regimes. Through her widely circulated project Material Speculation: ISIS (2015–2016), Allahyari used 3–D mapping to recover Southwest Asian and North African cultural heritage from destruction and from Western institutions’ claims of ownership. In this conversation, Allahyari discusses her recent use of multimodal AI models and 3–D imaging to re-figure queer and nonhuman agents in West Asian archives by drawing from ancestral knowledge to generate as-yet-unseen representations.

Mashinka Firunts Hakopian: A representative of Christie’s, commenting on the algorithmically generated La Famille de Belamy (2018) series [constructed by Paris-based arts collective Obvious] noted, “It may not have been painted by a man in a powdered wig, but it is exactly the kind of artwork we’ve been selling for 250 years.” Your series, Moon-Faced (2022), offers a markedly different approach to AI. This series uses an AI model trained on Qajar dynasty portraiture to paint genderless portraits and recover queer forms of representation that precede the influence of European visual culture. To start off, I wanted to ask you to speak to the origins of this project.

Morehshin Allahyari: I was interested in finding a relationship between an AI system and a history of the Qajar dynasty. There’s this article by Afsaneh Najmabadi that I came across, in which she specifically delves into these questions of gender and gender representation within the history of the Qajar dynasty. Culturally, as Iranians, we all know this dynasty—which goes back to 250 years ago—as a time when gender norms were very different than what we understand as contemporary gender norms. Definitions of beauty for men, women—they were very different.

So the word moon-faced, which is ماه طلعت in Farsi, was used for men and women as a way to define the beauty of both. The paintings of the Qajar dynasty follow the same trajectory. There are a lot of portraits where you don’t know if there are two women, if they’re a man and a woman, if they’re two men.

And I love that about that history, how actually we’re so stuck about the ways that we differentiate between men and women in representation and beauty and gender in the contemporary. But then you go back only 250 years ago, in a country like Iran, and you see that, wow, there is just a whole different set of values and beliefs and systems being played out.

I was doing research around this history, and at the same time, came across this VQGAN+CLIP. To also give her credit, Emily Martinez, she taught me how to use this library. In that process, I was researching these archives of [Qajar dynasty] paintings. When you look at the beginning versus the end of the 19th century within the Qajar dynasty, you see a change from this queer, nonbinary representation to [something] becoming more distinct in terms of “this is a man,” “this is a woman.” In the article I mentioned by Afsaneh Najmabadi, she talks about different reasons for this [shift, such as] the introduction of camera technology to Iran, which then gives painters more influence from the Western style of painting, and also Iran going through Westernization at that time.

With the AI library that I was using, I wanted to see how I could collaborate with this machine to undo and repair this history of Westernization. Obviously, this is a double-edged sword, because I’m also dealing with a library that itself is very dominated by Western data and Western history. And from the data to the material it pulls from visually, the archives that it uses obviously are dominated by the Global North.

Morehshin Allahyari, Moon-faced ماه طلعت, Hamraah [fragment], 2022, still image from video [courtesy of the artist]

I would give it words … and then, based on the kinds of phrases it would receive, it would generate these images. But I was also feeding it the specific paintings that I wanted it to change for me. If I didn’t do that, it would make up something completely different. It would never arrive at a Qajar painting, because, I guess, it does not have enough of that material to pull from. So, you already see the lack of this kind of data when it comes to, let’s say, the history of Iran or the words “Qajar dynasty.” Without feeding it the images that I wanted it to undo, it would not be possible to create. Plus, I’m dealing with typing in English, another language, again, that probably has more limitations when it goes back to history in a country like Iran, where this material is more available, perhaps, in Farsi. So there’s lack of data, and then there’s bias. If I would put in a phrase like, “two lesbians holding hands,” for example, immediately it would add a rainbow.

[For me] to train this AI, we were training each other, almost. [Given the image] library that I was working with, I was trying to figure out how else I could trick it to give me what I wanted it to give me, which was to undo these images and make them, once again, queer. And I was also trying to think about the whole process of working with an AI as an act of undoing, as an act of unlearning.

MFH: Let’s move on to She Who Sees the Unknown (2017–2021), where you use 3–D modeling to visualize monstrous feminine and/or queer figures of West Asian origin. The project is populated by figures like Huma, a demon with three heads and a tail, who summons fevers, and the Laughing Snake, a serpent-like figure of immense power who’s eventually undone by her own uncontrolled laughter at seeing her image in a mirror.

Morehshin Allahyari, She Who Sees the Unknown: Huma, 2016, image of 3d Printed sculpture [courtesy of the artist]

So, in your retelling, the laughing snake becomes an avatar for hysteria, gendered morality, and the experience of “living in a female body in the Middle East.” And you note in the description for the project that jinn historically represent one of “the three sentient creations of Allah.” I’m curious, what kind of knowledge do jinn conjure in your retelling? How do they call on us to re–evaluate historically feminized or otherwise gendered forms of knowing?

MA: She Who Sees the Unknown is a project that I got obsessed with because I came across manuscripts in 2016 that had illustrations and stories about mythical beings and spirits, from jinn to monstrous beings. The beginning of this project was, again, the lack of history, of stories, around these kinds of figures in the Middle East or in North Africa—in the mythology of that MENA region, or Islamic countries—about figures that are not male. Growing up in Iran, I always came across figures that were male, and stories about them that are culturally known. So first, I wanted to look for figures that did not fit into this one gender representation. And then, second, I became interested in the idea of the jinn, who in the Quran is talked about as a spirit made of smokeless fire. So that can be good or bad. If angels obey and devils disobey, then jinn, like humans, have the agency to decide.

MFH: Rerouting Donna Haraway’s oft-cited statement that she would rather be a cyborg than a goddess, you’ve written that you would [prefer to] be a “jinn rather than a cyborg.” What does it mean to claim the status of a jinn over and against that of a cyborg?

MA: In popular culture in the Middle East, we hear a lot of stories about the jinn. And one of the things that we always hear about is that they are a mix of human and this other thing, which is nonhuman. They say that if you want to know if a person who maybe showed up somewhere weird, who you didn‘t expect, is a jinn or not, you look at their feet. If they’re made of hooves, then you know it’s a jinn.

To me, this [combination] connects the jinn to the idea of the cyborg—the cyborg being this figure who is a mix of human and nonhuman. A cyborg is different than a robot, different than just one being. And what’s interesting about a cyborg is that it’s a mesh of two things. And it’s exactly like that with the jinn. Jinn were also, when I started this research in 2016, very popular spirits and figures in our culture, who were rarely thought about as [ones] who give the potentiality and possibility of becoming other things within the world.

MFH: Beautiful. I’m wondering, to what extent does the project frame the nonhuman intelligence of jinn as aligned with the nonhuman intelligence of computational systems that foresee, predict, or produce the as-yet unknown?

MA: First of all, I love this question. And yeah, I feel like that’s the potentiality of the jinn as a figure. You can befriend a jinn, or you can summon a jinn and befriend it, or you can be possessed by a jinn, right? You can use the power of the jinn to enter or channel yourself into other worlds. That comes with a set of talismans. There is a whole tradition of talisman writing, or Doaa-nevisi, which means “writing prayers,” where you summon the spirit of the jinn as a way to influence something in the future, as a way to remove an object that you don’t want to be somewhere, or as a way to find something … entering all these different dimensions of time and space.

When it comes, then, to the future, or predicting something or producing something that is not yet known, that’s exactly what a jinn is known to do. And if you’re possessed by one, there is that trouble, the horror of all the things that could happen to you that then interrupt some kind of flow, or some way of being in your life. It’s almost like hacking into a system, right? So maybe, actually, jinn are a kind of hacker.

Morehshin Allahyari, She Who Sees the Unknown: Aisha Qandisha, 2018, still image from video [courtesy of the artist]

MFH: That’s fantastic. I think that’s an essay unto itself. I’m going to switch gears a little bit and ask you about the specter of digital colonialism, which looms large in much of your work as a kind of force against which to wage struggle. You define digital colonialism as a framework for critically examining the tendency for information technologies to be deployed in ways that reproduce colonial power relations. And in earlier works, [such as] Material Speculation: ISIS, you respond to forces of digital colonialism by using 3–D modeling to recover Islamic cultural heritage from the dual violence of ISIS destruction and the claims of ownership issued by Western cultural institutions and tech companies that purport to act in the name of cultural preservation. So, I’m curious about how more recent projects like Moon-Faced and She Who Sees the Unknown represent responses to those same forces of digital colonialism.

MA: As I mentioned, with Moon-Faced, there’s the process of trying to undo something that happened because of Westernization in Iran, and at the same time trying to work with a system that is already biased or has a lack of data. Then, with She Who Sees the Unknown, part of the five years of working through this project was gathering an archive. That process became very difficult, sometimes, because of the gatekeeping of a lot of Western institutions. I decided the way that I wanted to build this archive and represent it on a website was to think about the question, how do you protect knowledge while you give access to knowledge? And to also resist the idea that open source is always good. To ask the question, who is this data for?

On the archive of She Who Sees the Unknown, I created four layers of access to information. So if you know [only] English, you can only have access to the first layer of the archive, which includes around 12 PDF files. And then, to get to the second, third, and fourth layer of the archive, you have to know either Farsi or Arabic, because you have to basically solve these puzzles—these cultural language codes—that I put in front of you. And then it will get unlocked. As you go deeper and deeper into the layers of the archive, the materials that are there become much more unique and rare, things that it was really hard to have access to.

People talk about decolonizing all the time. If you think about ways of building systems or platforms where you can actually experiment and really practice what decolonizing can look like … I think I was trying to see how close I can get to that. This project showed me that once I made those kinds of filters, then I got the attention of a different community of people who were interested in the archives, people who spoke Arabic and Farsi, and also very much a queer community. To me, that was really the value of doing this project and targeting a specific audience whom I wanted to have access to this knowledge.

Morehshin Allahyari, She Who Sees the Unknown: Kabous, The Right Witness, and The Left Witness, installation detail, 2019, 3d printed sculptures and VR video, [courtesy of the artist and The Shed, New York City]

MFH: It’s such a poignant way of organizing access—you can access the knowledge only if it’s in some way local to you. On the subject of accessing knowledge, you mentioned earlier in the conversation that one of the things that your work responds to is the false conflation of the past with history and the future with technology. And I see your work as exemplary of a set of practices that I’ve been thinking about under the rubric of “ancestral intelligence”—practices that engage AI and emerging technologies while refusing the violent rhetorics of innovation and technoscientific progress; practices that conjure non-Western pasts and ancestral knowledge to generate futures and future technologies otherwise. For example, you’ve located the origins of your fascination with jinn in the stories transmitted by your grandmother in Iran about her encounters with otherworldly beings. I’m curious—what role does ancestral knowledge or ancestral reclamation play, more broadly, in your work?

MA: I truly think it’s in my blood. I am half Kurdish. My dad is Kurdish, and my mom always made the joke, “Oh, this is your Kurdish side coming out,” because Kurdish are known as very resilient toward any kind of oppressive power. So, I really think it’s more of a blocked memory in me that is, like, “No, it can’t be that way. I have to find another way.” I don’t see my practice as one that sits in the cave of an individual practice, but rather [one that] builds worlds with other people. Specifically, in this case, people in diaspora from the MENA region. So, I think that’s where the ancestral knowledge comes from. That’s what I’m also trying to leave behind, something for the future. It has to be this line of taking from the past and passing it forward.

MFH: That’s extremely poetic, taking something from the past and passing it forward. It segues into my question for you on re–figuring, which is a term that you’ve used to describe your work as a feminist and activist practice of retrieving the past … to re–imagine alternate presents and futures. I’m curious about how re–figuring operates in Moon-Faced and She Who Sees the Unknown, and how you see re–figuring in relation to other critical models of engagement with the past, [such as] Saidiya Hartman’s critical fabulation or Kodwo Eshun’s countermemory.

MA: I think about this phrase which is … how do you remember the future and then look forward or predict the past? Something like that. When I think about re–figuring, it’s about going back and speculating on the past—and what was something unknown about the past that I’m trying to find?

In She Who Sees the Unknown, if you looked at [the figure of the Laughing Snake] from a feminist position, a position that did not see this female jinn figure as just a monstrous figure, and didn’t see monstrosity as a thing that was about women being monsters, but rather as a position of power, then you could reread this story in a different way. I always try to remember that there’s something here that I can speculate [upon] or reread in a way that was not told to me. Then, in re–figuring, it’s not about just shuffling something. It’s about a much more complicated process, re–figuring this idea of an alternate future. Because if you can re–figure the past, you surely can walk into a different kind of future.

Morehshin Allahyari, She Who Sees the Unknown: Kabous, The Right Witness, and The Left Witness, 2019, image of 3d models [courtesy of the artist]

MFH: Amazing. Is there anything that we haven’t touched on that you want to add?

MA: I think I would say just one more line about the cyborg. Obviously, Donna Haraway has always been one of my inspirations. Her texts, the way she thinks and writes. But then I always wondered, if we had someone that theorized and thought about a figure like Haraway did at the time that she did, but that person was not from [the US], what would [that] Donna Haraway dream about? And when I was thinking about the jinn and building these stories and potentialities and possibilities around the figure of the jinn, that’s the closest I came to an answer: that if it was not the cyborg, it should have been the jinn.

MFH: And still can be, I hope.

Mashinka Firunts Hakopian is an Armenian writer, artist, and researcher born in Yerevan and residing in Glendale, CA. She is an associate professor in technology and social justice at ArtCenter College of Design. In 2021, she was a visiting Mellon Professor of the Practice at Occidental College, where she co-curated the exhibition Encoding Futures: Critical Imaginaries of AI with Meldia Yesayan at OXY ARTS. With Avi Alpert and Danny Snelson, she makes up one-third of the collective Research Service. She is a contributing editor for ART PAPERS, and her writing and commentary have appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books, Performance Research journal, Art in America, Hyperallergic, and Meghan Markle’s Archetypes. She is the author of The Institute for Other Intelligences (X Artists’ Books, 2022).

Morehshin Allahyari (Persian: موره شین اللهیاری) is a New York–based Iranian-Kurdish artist using 3-D simulation, video, sculpture, and digital fabrication as tools to refigure myth and history. Through archival practices and storytelling, her work weaves together complex counternarratives in opposition to the lasting influence of Western technological colonialism in the context of SWANA (Southwest Asia and North Africa). Her work has been part of numerous exhibitions, festivals, and workshops at such venues throughout the world as the New Museum, MoMA Centre Pompidou, Venice Biennale Architettura, and Museum Angewandte Kunst, among many others. She is the recipient of the United States Artist Fellowship (2021), the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant (2019), the Sundance Institute New Frontier International Fellowship (2019), and the Leading Global Thinkers of 2016 award by Foreign Policy magazine. Her artworks are in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Current Museum of Art. She has been covered by The New York Times, BBC, Huffington Post, WIRED, National Public Radio, Parkett, frieze, Rhizome, Hyperallergic, and Al Jazeera, among others.

***

This feature originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Spring 2023 // Artificial Intelligence.