Bodies / Antibodies

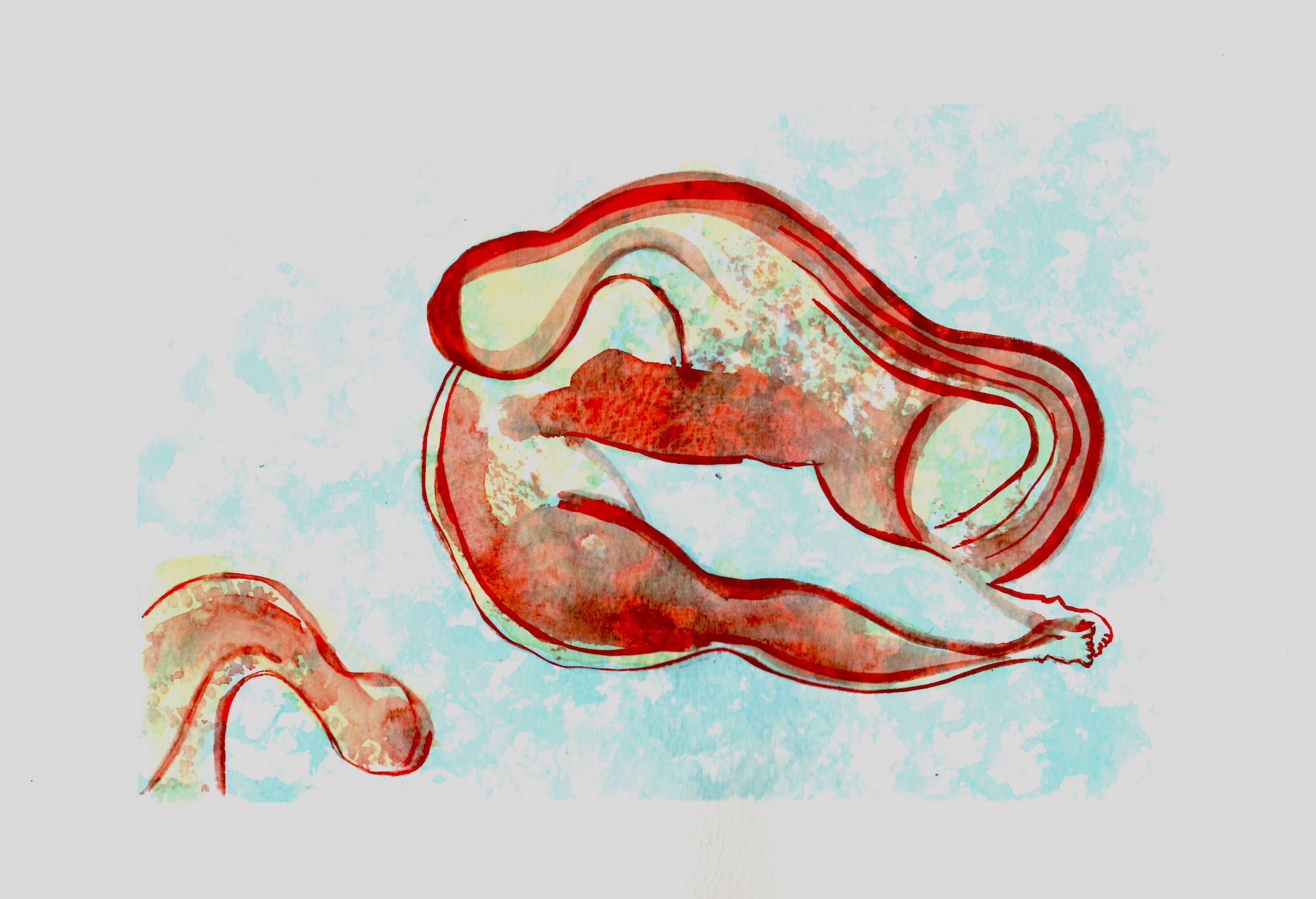

Miriam Simun, Leaking, Merging, Blurring (series), watercolor on paper, 10 x 4 inches, 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

On the fourth day of the lockdown we put on head-to-toe Lycra suits (heads, feet, even fingers covered) and try out the transhumanist-cephalopod practice I’ve been building the last few years. It involves lots of touching. We touch the carpet, touch the couch, touch the floor, touch the piles of records everywhere, touch the plants, touch the speakers, touch the walls. We touch each other. First fingers and forearms, then shoulders, legs, breasts. It’s not sexual, but there is a desperate, starved sensation—grasping and rubbing. The Lycra is silky smooth, the feeling of a 90s Slip ’N Slide in a friend’s yard. We stay dry.

We make sounds together. A low humming builds slowly. Suddenly we’re wailing, separately, yet aware of each other. Not crying—more like dying animal sounds, like the stray cats in the alley outside our kitchen window. I welcome the familiar onrush of body, an ocean of sensation, the luxury of it all. It’s her first time, and I watch something break open. Afterward, she’s shouting from the balcony, releasing euphoria.

On the eighth day of the lockdown I go for a run. It’s been years; my chest and ass burn, long minutes to catch my breath between sprints. My breathing-wheezing is so intense that people cross the street to get away. I take note of these moments, when it is useful to be regarded with suspicion: a body carrying a viral load.

I enjoy this new city emptied of cars. I run the wrong way along the center of a normally busy road. My body feels intensely free. I turn the corner to face a narrow gap between car and sidewalk. I keep hurling myself forward. As I lurch past, the man at the wheel extends a blue-gloved hand and half-gropes-half-swipes my thigh. I stop feeling free. I feel weirdly grateful that it was gloved, the hand. I take note of the reminder: no feeling lasts forever. That meditation app I downloaded this morning is on to something.

Miriam Simun, Leaking, Merging, Blurring (series), watercolor on paper, 9 x 12 inches, 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

On the 12th day of lockdown I crave meat. Red, bloody meat. I don’t usually buy much meat and ponder how I will explain in my broken Portuguese which animal part I want to eat. I imagine repeating, over and over, “Eu quero uma coisa como isso,” while furiously pointing to my ribs.

The butcher shop is small, two bodies behind a counter—one in the corner, taking payments through a Plexiglas divider. I wait my turn outside. One out, one in, the butcher shop as Berghain. I step inside. In a glass case, body parts of various shapes and colors sit under fluorescent lighting. Turkey to the left, pork to the right, beef in the center. Beyond that, I have no idea what I’m looking at.

In the end I go with what is easy to explain, ground turkey and a piece of flesh labeled “Osso Buco.” I step back from the counter just as a woman enters the store. I sidestep to make space between us but end up grazing a man who is paying. I move sideways to get away but realize that not only is there nowhere to go, but there is now a momentum in my body that has to be released, or else I’ll fall. I end up lifting both hands in the air, a bag of meat in each clenched fist, and spin, twice.

Miriam Simun, Leaking, Merging, Blurring (series), watercolor on paper, 9 x 12 inches, 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

Miriam Simun, Leaking, Merging, Blurring (series), watercolor on paper, 9 x 12 inches, 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

On the 18th day of lockdown I wake up and feel only dread. I decide to cancel the day. I will forget I have a body, that it used to go places, touch, be touched, do anything other than move around regarding all obstacles with suspicion of contagion; or else safely sit staring at various-sized blue-tinged screens, worrying—about my grandma, my Italian friends, my New York friends, the migrants in Greece, the migrants in US cages, how I’m going to make rent. I leave my Mediterranean black-out blinds closed, take three Xanax, and get back into bed. A new season of Ozark was released, and I dedicate myself to it wholly. Two episodes in, a stray thought flits by, questioning the politics of … I push the thought away, push myself back out of myself, into the screen, into the fast-changing narrative, the boats speeding away as the water glistens.

Suddenly an alert on my phone: an international bio-artist Zoom call. I consider. I tense from the thought of joining. I tense from the thought of failing to do one simple thing today. I compromise—two more Xanax and I call in, mute on, body horizontal.

One participant asks us to join a “social sculpture,” inspired by his mild cold. To purchase antibody tests directly from manufacturers and test ourselves. An efficacy debate ensues. I skip the sculpture and focus on the antibody. Maybe I can see people again, touch them, breathe together. Antibodies are the only thing that can bring me back into my body.

Miriam Simun, Leaking, Merging, Blurring (series), watercolor on paper, 9 x 12 inches, 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

Etymonline.org defines an antibody as a “‘substance developed in blood as an antitoxin,’ 1901 … probably a translation of German Antikörper, condensed from anti-toxischer Körper: ‘anti-toxic body.’”

The anti-toxic body.

It’s tricky. An anti-toxic body is in fact a toxic body—not to me, but to the virus I become host to. Suddenly a previously intellectual knowing burrows deep inside my skin: my body’s survival has always depended on the proper balance of entire colonies of alien microbes living in the corners of my mouth. It just so happens that this particular alien might kill me, although probably not, but it could kill my grandmother via me.

My body would thus become the toxic body.

On the 24th day of lockdown I catch a plane across the Atlantic body. The airport is sparsely populated, human bodies moving in soft round patterns while navigating various processing points: check-in, security line, boarding gate. Waiting for the train between terminals, I stand two meters away from a woman in a blue mask, black gloves, pink baseball hat, and a clear piece of vinyl reaching to the center of her chest—human Saran Wrap.

The train arrives, its doors stay shut. “Please wait for the train to be screened for your security,” says a pre-recorded voice over the intercom. A guard walks back and forth inside the train. I am confused. She’s not cleaning anything. Finally I realize that she’s looking for bombs, not viruses. My gut drops. The post-9/11 security apparatus is about to double down. Who will get the worst of its excess this time?

Later a friend will question my motives for leaving: “You are impatient, you need to take action in the face of uncertainty, you can’t just wait and see.” I can’t entirely dismiss this assessment. For now, I still believe the reason that drove me to leave this calm socialist democracy for the land of the uninsured is reasonable—a term I will admit is slippery these days.

I do not run from toxic bodies that threaten to invade my body, but toward a body that has nourished me, that I care deeply about and am frightened for. A body less likely to produce anti-toxic-bodies fast and strong enough to kill the toxic bodies that could cause this loved body to shut down its functions. The cruel irony is that some of the likeliest threats to this loved body are toxic bodies lodged in my own body, that might transfer then to her.

These loops and Venn diagrams of bodily relations are confusing. They can’t settle properly in my mind. I am reminded of Astrida Neimanis: “Our own embodiment … is never really autonomous … we require other bodies of other waters (that in turn require other bodies of other waters) to bathe us into being.” Neimanis asks, what if we think of bodies not as jumbles held together by skin but, instead, as flows that leak? On the flight I fight this notion with all I’ve got: bra cup over nose and mouth, eye mask over eyeballs, headphones over ears. All plugged up.

Miriam Simun, Leaking, Merging, Blurring (series), watercolor on paper, 9 x 12 inches, 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

Neimanis lists things with “aqueous facilitative capacity”: human wombs, sea monkeys, amphibious eggs, primordial soups. I look out of the airplane window and float away, my body housing a primordial soup. Who knows what might grow in there? “A rat’s nest. Someone who is late in washing his hands in the morning. White snivel, and children who sniffle as they walk. The containers used for oil. Little sparrows. A person who does not bathe for a long time even though the weather is hot,” from Sei Shōnagon’s list of “Things that give an unclean feeling,” written a thousand years ago. Upon landing, I am asked: have I been in touch with livestock? No one takes my temperature. The date is April 4th.

On the 26th day of lockdown, 2nd of total isolation, I crawl onto the fire escape of my quarantine apartment. Birds sing, helicopters whirl, and I fit each leg each through an opening between the metal bars. Limbs dangle six stories up, the safety of containment. A decade ago in New York, my grandma turned to me and said: “Whoever built all these fire escapes sure made a lot of money.” I was surprised that this Soviet Socialist citizen (from birth to age 55) so clearly saw the capitalism in the infrastructure. I later read: COVID-19 vaccine is coming fast, thank capitalism for that (also from an ex-Soviet, this one with an investment blog).

“This country is horrible,” I tell my grandmother on the phone, recounting stories of dying workers in the news. Da vsey strane ujastnaye, she replies: all countries are horrible. I am reminded of my grandfather, the reluctant refugee, who died last fall. before this all began, but left me with an aptitude for salvaging humor in the darkest places: “I only live in great empires.”

On the 29th day of lockdown I laugh out loud. A reporter asks the president why he and all his aides stand so close together, ignoring distancing guidelines. Big Orange waves his hands while the camera pans: the VP’s feet are firmly planted, but his body leans. At full tilt he’s 65 degrees from horizontal—a dance move from some early–90s music video.

I stop laughing when I watch a viral video made two weeks ago by Jason Hargrove, a city bus driver who died today. “This is real. I’m out here, we out here, moving the city around, trying to do our jobs and be professional about what we do. Again, I ain’t blaming nobody—nobody—not the city, not the mayor, not the department, not the state of Michigan, not the government—nobody—not the president. I blame that woman who stood on this fucking bus and coughed.”

It hits me in the gut. How deep the pathogen of individualism has lodged. The man calls out, by name, every responsible actor he does not blame. Detroit began to provide masks only after Hargrove’s death and fame. And all the other drivers in all the other cities?

Miriam Simun, Leaking, Merging, Blurring (series), watercolor on paper, 9 x 12 inches, 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

I blame the city. I blame the mayor and I blame the department and I blame the state of Michigan and I blame the president. I blame the fucking government for this man’s death.

And also, my mind zooms in and out of scale, at times retreating to the cosmic. No protection is foolproof, no border impermeable. I read George Saunders’ letter to his students: “the world is like a sleeping tiger and we tend to live our lives there on its back.”

He continues: “I saw this bee happily buzzing around a flower yesterday and felt like, Moron! If you only knew!” I listen to his former student respond, that she looks at trees, impervious to this virus, and finds solace. My mind is only shouting: “BUT SOMETHING’S ALREADY COMING FOR THE TREES!”

People write that in this moment we can learn to change carbon-based economies, prevent the worst of the climate crisis. I watch the US government suspend anti-pollution governance while funding airlines instead of high-speed rail. What is the antibody for the Anthropocene?

From Wikipedia: “an antibody can tag a microbe … for attack by other parts of the immune system, or can neutralize its target directly.”

“Neutralizing the target.” I can’t remember where I heard this phrase before. The Terminator? I remember, near the start of this pandemic, watching Arnold Schwarzenegger sit at his dining room table, feed two miniature ponies directly from his plate, and instruct the country to stay home. Okay, so, if the ponies are the pathogen and Arnold is the antibody, he either starves the ponies himself, or marks them and instructs security to kill them on sight.

Please bear with my analogy. I do not have a biological mind. Cardi B’s refrain “shit is getting real” has been on repeat in my mind for weeks, and it’s been a month since I had another body in my bed. Come to think of it, it’s been exactly 30 days since I had direct contact with another person’s skin.

A friend writes me: “antibodies are NOT a guarantee of immunity—they are a record of exposure.”

“We simply don’t know yet what it takes to be effectively protected from this infection,” a pathology professor tells Scientific American. I read about immunity licenses in Germany, bio-passports in Chile, and 70 different companies vying to sell antibody tests in the US. Decisive action in the face of uncertainty.

Miriam Simun, Leaking, Merging, Blurring (series), watercolor on paper, 9 x 12 inches, 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

On the 33rd day of lockdown, a total calm—sans Xanax—comes over me. I no longer want to go outside; this quarantine sublet has become my womb. I read that human wombs were made with viruses. Our ancestors got sick, and we got viral DNA that allows “babies to fuse to their mothers.”

I was obsessed with pregnancy as a child. I loved The Cosby Show episode wherein Cliff gives birth to a six-foot-long submarine sandwich (he dreams). Thinking of Cosby brings me back to Neimanis and “the phallogocentric regime.” It “supports a forgetting of the bodies that have gestated our own, and facilitated their becoming.” She writes of discrete individualism, anthropocentrism, and phallogocentrism: “deeply entangled, mutually enforcing claims of each other.”

These days, neoliberal news outfits are full of statements decrying the end of individualism. Anthropocentrism is bafflingly ignored.

I read how the containment and crowding inherent in industrial meat systems are perfect breeding grounds for novel viruses, letting them pass easily, mutate, and recombine to form new and stronger strains. I read about PEDv, a virus that seven years ago killed seven million pigs, within twelve months. To fight transmission via human carriers, managers prohibited employees from living together. A wife cared for piglets, her husband slaughtered them. Because killing is always better paid than caring work, she left her job and he kept his.

A segregation based on bacterial interactions. Age of the blue glove.

I reconsider, in this light, the blue-gloved hand, groping from a car window—a transgressive, anti-segregationist act? Nope. Still gross—and I wonder why I desire to accommodate oppressive acts against my body. I feel Neimanis’ whisper in my ear.

Miriam Simun, Leaking, Merging, Blurring (series), watercolor on paper, 9 x 12 inches, 2020 [courtesy of the artist]

On the 35th day of lockdown I break total quarantine to meet D. It strikes us both, the inability to touch. I feel an aching on the surface of my chest and running down both arms. We compromise. We lie down on the grass and form a single line—head to feet to feet to head. We touch shoe soles and move our legs together, until our abs and then our minds get tired.

On the 37th day of lockdown I awake staring blankly at The New York Times, then jolted by surprise: “bodies gathered ….” Who’s gathered? It’s over? What now?

But no, “antibodies gathered” from recovered bodies are being collected and re-injected into bodies of the sick. We survive by managing porosity. If the danger lies in leaky bodies, so does hope.

“Can you hold one another tonight in the blur, so that one and another are no more?” writes Fred Moten.

Leaking and fusing and merging and blurring.

There are so many ways this could all go, good and bad. Bare exposure of oppressive racial-capital structures begins to shift after confronting this wound; or, just a simple, vulgar, doubling down.

Maybe what’s to learn, in months of endless sitting, is precisely this: to sit. To sit in, to sit with, to sit and see … the leakages, the blur, how best to be, how best to care, how best to be care-ful.

This text was written in the ancient past. Now: everything has changed. Nothing has changed. I think about how it feels, to be crushed together with thousands of other bodies in the street—not sitting but marching, masked, in defense of Black lives. The pandemic has brought a heightened awareness of bodily permeability to this crowd, consciously becoming, in a multitude of ways, a giant single body, while also starkly and violently divided by difference, because of real and perceived characteristics of our individual bodies. In hopeful moments I think: perhaps this virus, which laid bare the leaking of our neighbor’s body into our own, forces us to witness, more intimately than ever before, the violence enacted against Black bodies, fellow bodies. In March the G20 gave us “a powerful reminder of our interconnectedness and vulnerabilities,” and in May we took this wisdom to heart, and to the streets. In hopeful moments.

In other moments, I feel unease and think, let’s take what we can get. Quarantined minds and angry souls bring their bodies to the streets, and it appears, for now, that enough body mass in and of itself can start to shift something. Now even the most privileged have gotten the tiniest taste of what it is for their government and fellow citizens to have total disregard for their lives. “And now my ‘other’ is happening to you. Now degradation and moral compromise and your body breaking down are happening to you,” writes Hilton Als. We must fight for every “othered” body as if it were our own—for, in a very real sense, it is. We keep bleeding, keep seething, keep leaking, and keep fusing—because of, and in spite of, into and out of, each other. Nothing has changed. Everything must change.

***

This feature originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Summer 2020 // Living & Working.