Lili Dujourie, Mimesis, installation view, 2022, [photo: Sigrid Spinnox; courtesy the artist and the Antwerp Public Art Collection (Kunst in de Stad – Middelheim Museum)]

Radical Radixes—On Lili Dujourie’s Mimesis

Share:

Lili Dujourie is well-versed in the political potential of material and form. Her early installation Amerikaans Imperialisme (1972) critiqued American and masculist supremacy within, and beyond, the art world. Consisting of a metal slab leant against a painted wall, with the part behind the slab left unpainted, the work challenged prevailing minimalist assertions of universality coming from US artists and critics. Necessarily, minimalism’s aesthetic informed how Amerikaans Imperialisme afforded pleasure to the viewer. The work is thereby implicating us by bringing political awareness to our aesthetic experience.

Fifty years later Dujourie deploys similar reflexivity in Mimesis (2022), a bronze sculpture recently installed in front of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, that is both monument and a critique of monumentality. By artificially oxidizing its surface, she creates the illusion that the work has long been there. Mimesis thus mimics the weathered statues nearby and elsewhere, including ones that are controversial primarily due to the people they represent—such as, most pertinently, statues of the colonial tyrant Leopold II throughout Belgium (although the one in Antwerp’s Ekeren district was removed in 2020, and others are being considered for “recontextualization”). If mimesis is understood in the classical (Greek) sense, broadly denoting imitation or representation—through which art mimics or “acts as” its subject—it could be said that Dujourie highlights the contemporary political relevance of age-old, philosophical debates around the creation of likenesses. Ancient questions about whether it is morally right or even possible to depict reality (questions that informed modernist abstraction) are treated as pertinent to postcoloniality. For Dujourie’s monument is not a literal representation of any figure. Eschewing individualism, it is a “theoretical object”—to use Mieke Bal’s term to describe Dujourie’s works—positing representation as discourse, and monumentality as a problem of representation.1

Lili Dujourie, Mimesis, installation view, 2022, [photo: Sigrid Spinnox; courtesy the artist and the Antwerp Public Art Collection (Kunst in de Stad – Middelheim Museum)]

The work consists of an upright, kinked, and broken cylinder, from the base of which protrude zigzagging, forked rods; the whole evokes a barren tree trunk, its roots growing down the sides of its plinth, clinging to it. Two of the roots reach the pavement and one touches the steps, mimicking the way that some trees survive on rocks or walls by rooting around them. The roots provide both nutrients and stability: They, not the plinth, hold the tree in place. The plinth poses a common problem of monumentality. It conjures individualism, hierarchy, idolatry, and institutional and state power—as do the museum or the art market—but it is hard to critique when it operates as the artwork’s host. By colonizing the plinth, and by breaking the threshold between the realms above and below, center and periphery, one and many, Mimesis offers a potential break from the established terms of its context. It does not do away with the plinth, or pretend to dismantle its authority, but it does problematize the plinth’s dominion. The work thus recalls Dujourie’s experiments with velvet drapery in the 1980s, which foregrounded the fabric used to aggrandize individuals in historic, painted portraiture—except, here, the framework has not become the subject, but rather the subject overspills the framework, reproducing itself, as plants do, before our eyes. The form depicted in Mimesis performs its battle for self-determination and for collectivity beyond the privileged singularity that plinths normally uphold.

Lili Dujourie, Mimesis, detail, 2022, [photo: Sigrid Spinnox; courtesy the artist and the Antwerp Public Art Collection (Kunst in de Stad – Middelheim Museum)]

As a work of eco-rebellion, Mimesis recalls a 2017 alternative proposed by students for the statue of Leopold II in Place du Trône in Brussels, which involved the monument being overgrown by poisonous and healing plants.2 Mimesis is (anti-)monument and plant, its roots (potentially, imaginarily) infiltrate the ecology of its placement. This relation upends that of monumental statues, which are simultaneously surveillant and neglectful—overlooking, in both senses of the word. Mimesis comes down to meet us, drawing us in to experience semi-haptically the texture of its making. Because the trunk is slender relative to the plinth, the roots’ exact origin is obscured; the two parts are connected because we automatically perceive them to be. And yet the blind spot is marvelously disorienting, leading us to question what we’re looking at—whereas monuments tend to forbid questions—to circumnavigate the plinth, to go up the steps and glimpse the work from above. Closer inspection reveals the textured brushwork with which the oxidizing chemical was applied. Dujourie’s mimesis is not replication but self-aware praxis. The clue to Mimesis’ anti-monumentality is in the radicality of its arboreal form (radix = root), which directs its energies downward and outward. As Emanuele Coccia explains in The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture, roots are sociable: “The advantages they bring are those of networking, and not those of isolation or distinction.”3 Conversely, conventional monuments are self-absorbed and demand our obedience without ever reaching us.

Mimesis was commissioned by Antwerp Public Art Collection as part of an initiative curated by Samuel Saelemakers to bedeck the city with self-aware, socially progressive art. Another new work, Congolese artist Sammy Baloji’s The Long Hand (2022)—on the bank of the River Scheldt—also effectively dismantles the hierarchies and irreproachability of plinths. Baloji made a brick platform of low benches or steps that circle the work’s main component, a large lukasa, or “long hand,” a board-shaped mnemonic tool traditionally used by the Luba of the southern Congo. The steps invite viewers to gather informally around the lukasa and exchange stories. Like the colonial monument, the lukasa is a preserver of narrative. The former, however, silences the stories of the colonized—which it nonetheless contains—in favor of a singular, unquestionable mythology. Baloji’s work provides a space for collective remembrance and storytelling to redress this long-corrupted balance. Since the colonial era, the River Scheldt has been the waterway for Congolese goods entering Antwerp. One such import is copper, an ingredient of bronze, out of which much of The Long Hand is made, in reference to this history of extraction. Another import is diamonds, replicas of which Baloji pins to his lukasa amid an outline of the naval route between Antwerp and the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s main port.

Sammy Baloji, The Long Hand, 2022, bronze, bricks and recycled plastic [photo: Tom Cornille; courtesy of collection Kunst in de Stad, Antwerp.]

Mimesis withholds any such explicit reference to Belgium’s colonial past, yet it engages with a material legacy in art theoretical terms. Plato was one of the earliest Western thinkers known to have recognized mimesis as a problem. His condemnation of mimesis—as it appears in books II, III, and X of the Republic, which pertinently revolves around civic life—responded to the impossibility of representing the essence, or “form,” of a thing, but also to the bad influence that certain likenesses could have upon the populace.4 Aristotle, by contrast, was more open to the idea, arguing that, if the figure set a good example—or, more importantly, if the viewer is well-informed enough to distinguish good from bad—surely, then, mimesis was acceptable.5 But who decides what or whom should be pedestalled? Whose history, whose goodness, does this individual represent? Plato might not have asked these exact questions, but they stem from his thinking: The mimetic individualism of traditional public statues obscures the complexities and nuances of the ungraspable whole by perpetuating a single story whose one-sidedness cannot be mitigated by an explanatory plaque. Dujourie encourages us to keep Plato in mind when we think about public statues. To ask who is, or who should be, pedestalled is not enough. What is required of us is to make a philosophical inquiry into the need to put people on pedestals in the first place.

In his 2013 overview of Dujourie’s career, Anders Kreuger found clues in Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s 1766 essay Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry as to how she teases the mind’s tongue.6 Dujourie represents concepts by physically manifesting “bodies” and metonymically performing “actions,” thus reflecting what Lessing believed were the mimetic functions of the visual arts and poetry, respectively.7 The result is always open-ended, neither body nor action fully completing the other. Witness this duality in Mimesis, which depicts the behavior of a tree more than it does a tree as such. Here, behavior imperfectly stands in for what cannot be literalized: an idea in formation—it mimics the form of a plant, whose growth is its becoming and its being.8

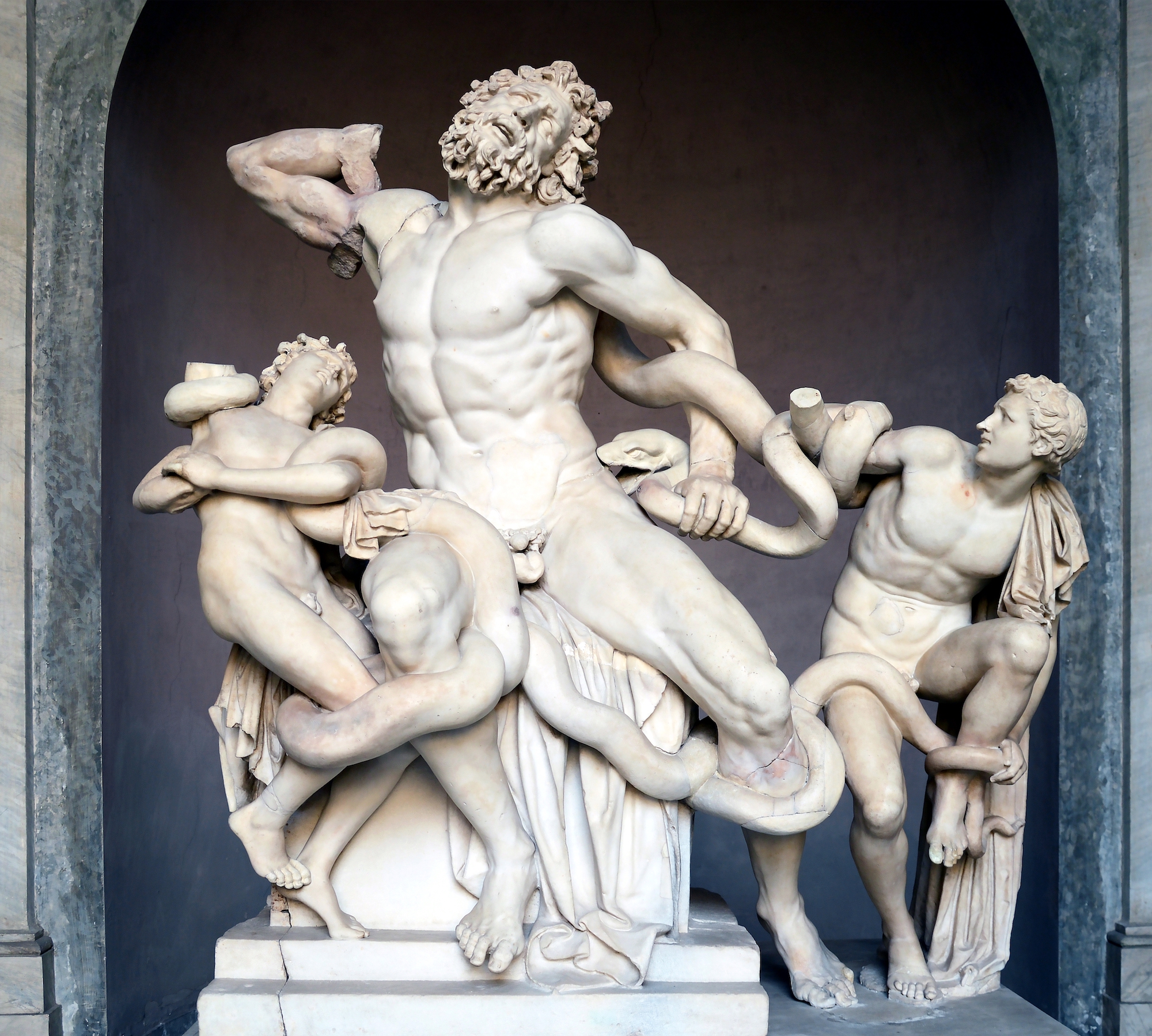

But what really makes Lessing’s essay appropriate here is its titular case study: the famed Hellenistic sculpture, believed to be a Roman copy of a Greek original, variably dated between the first century BCE and the first century CE, excavated in Rome in 1506, housed in the Vatican, and renowned as a Western paradigm of pathos. The sculpture, called Laocoön and His Sons, or sometimes Laocoön Group, is uncontainable, its entanglement of limbs and serpents tumbling from its “plinth seat.” In Dujourie’s Mimesis, each fork, kink, and breakage in the trunk and roots resonates with the psychological and physical pain that Lessing argued was the core subject of this ancient precursor—which, in both works, is felt proprioceptively in the body of the onlooker.9 Dujourie’s decades-old dialogue with art history warrants this comparison, not least because of her interest in Antwerp’s much-venerated 17th-century resident Peter Paul Rubens, whose portrait is carved into the façade of the Royal Museum, above Mimesis. Rubens drew upon the Laocoön to compose the vast triptych The Raising of the Cross (1610–1611), in the city’s cathedral.10 The affective angularity of the Laocoön—used by Rubens to epitomize Christ’s ecstatic, counter-reformist agony, and here essentialized in Mimesis—functions in terms of what Aby Warburg defined as pathosformel, archetypal visual tropes that carry emotion: the arched necks of Laocoön and Christ, the kink in Mimesis’ trunk.11

Laocoön and His Sons, marble, 82 x 64 x 44 inches [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

However, the affect of art also stems from what onlookers bring to it. Looking at Mimesis now (bearing in mind that the work’s state of becoming sets signification afloat, thus rendering it subject to change), I find it hard not to intuit some of the pain that has been silenced by monuments and expressed in their righteous vandalism. Statues of Leopold II are commonly sprayed with blood-red paint. His hands are never missed, the paint idiomatically indicting him for murderous tyranny. The gesture also reminds us of the notorious punishment meted out by the Belgian Force Publique: severing the hands of Congolese workers who failed to satisfy quotas. Such embodiments of once seamless irreproachability are thus forced to release the collective pain they were installed to suppress, as if the blood—not of Leopold himself but of those whom he harmed—that was long sealed within the king’s image were finally bursting forth. Dujourie attended Expo 58 in Brussels, which featured a “human zoo” of Congolese “natives”—an atrocity that had occurred already at the 1894 World Exhibition in Antwerp, where a living ethnographic display was presented across the square from Mimesis’s plinth.12 Furthermore, the sculpture’s resemblance to a blasted, or severed, tree evokes the suffering of “nature”—humanity’s presumed separation from which dovetails with the pseudoscientific violence of racism and the extractive motives of colonialism. Humanly made of humanly obtained minerals, it posits the agony of environmental catastrophe as something inextricable from our own actions. In Mimesis—which all but vandalizes its plinth—the turbulence of the Laocoön becomes anticolonial riot.

Mimesis is the first artwork to adorn the plinth on which it stands—grows, bleeds—since the building opened in 1890. The spot was originally intended for an allegory of Genius, as a counterpart to Léon Mignon’s Fame, across the staircase. For some reason, Robert Fabri’s proposal—a trumpet-blowing angel riding a lion—was never realized. By 1905, probably for the sake of symmetry, Mignon’s Fame had been relocated to the garden behind the museum; it finally returned to its original place in 2021. Fame consists of two figures: an idealized male nude and, behind him, the Greco-Roman figure of Fama, with a trumpet in each hand. The monument did not originally commemorate an individual, though it always had the effect of glorifying an exclusive—White—canon of beauty. Nevertheless, lust for heroism precipitated its renaming, and it was eventually, additionally titled Tribute to Anthony Van Dyck, in honor of Rubens’ most famous student. Dujourie turns away from any such glorification. Instead of genius—the divine inspiration that fills individual creators, often invoked to sanctify the actions of despotic rulers—she picks a theme that is social and open-ended. True mimesis is receptive (it bears the stamp of the world) and generative (it keeps stamping back). Objects mean what we bring to them. Sometimes, the invention of meaning is like a network of roots—intricate, mercurial, and beyond our control.

Lili Dujourie, Mimesis, installation view, 2022, [photo: Sigrid Spinnox; courtesy the artist and the Antwerp Public Art Collection (Kunst in de Stad – Middelheim Museum)]

Lili Dujourie, Mimesis, detail, 2022, [photo: Sigrid Spinnox; courtesy the artist and the Antwerp Public Art Collection (Kunst in de Stad – Middelheim Museum)]

Tom Denman is a freelance writer based in London. He holds a PhD in Italian Studies from the University of Reading, for which he wrote his thesis on Caravaggio and the noble-intellectual community in seventeenth-century Naples. His art criticism has appeared in ART PAPERS, ArtReview, Art Monthly and Flash Art.

References

| ↑1 | Mieke Bal, Hovering Between Thing and Event: Encounters with Lili Dujourie (London, Brussels and Munich: Lisson Gallery, Xavier Hufkens and Kunstverein München, 1998), 109. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Claire Debucquois, “Red Hands: Copper, Tin, Paint, Poems, Plants,” New Left Review 127 (January–February 2021), 91. |

| ↑3 | Emanuele Coccia, The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture, trans. Dylan J. Montanari (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019), 81. |

| ↑4 | Plato, Republic, 377e–398b, 595a–608b; see Nickolas Pappas, “Plato’s Aesthetics,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020), online. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/plato-aesthetics/ |

| ↑5 | Pierre Destrée, “Aristotle’s Aesthetics,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021), online. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/aristotle-aesthetics/ |

| ↑6 | Anders Kreuger, “The Actions of Bodies: Approaching Lili Dujourie,” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 34 (Autumn/Winter 2013): 108–125. |

| ↑7 | Ibid.; see also Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry, trans. Ellen Frothingham (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1887), 91. |

| ↑8 | Coccia, The Life of Plants, 14. |

| ↑9 | Cecilia Sjöholm, “Lessing’s Laocoön: Aesthetics, Affects and Embodiment,” Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 46 (2013): 18–33. |

| ↑10 | Kreuger, “The Actions of Bodies,” 118. |

| ↑11 | Colleen Becker, “Aby Warburg’s Pathosformel as Methodological Paradigm,” Journal of Art Historiography 9 (December 2013): 1–25. |

| ↑12 | Kreuger, “The Actions of Bodies,” 112. |