Meteorite & Monument

Share:

This essay originally appeared in ART PAPERS May/June 2003. It was reprinted in Fall/Winter 2020 “Monumental Interventions,” an issue that considered the history of artist interventions into the language, form, and function of public monuments.

***

Art is a quest for time. To be forever connected with the current and protected from the ravages of time is the most precious thing an artist can look towards—to stand against the cultural entropy of disinterest. No work of art embodies this desire more than the precisely rendered works of Donald Judd. So what irony and what lessons might be contained in the damage suffered by a twenty-year-old sculpture by Judd? What vandal would dare so blatantly to defy Judd’s ideals regarding monument and time?

John Chamberlain Building, variously titled works in painted and chromium steel, 1972 – 1983, detail. Architectural adaptation by Donald Judd (permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas) [Photography by Florian Holzherr, 2001, ©2003 Judd Foundation]

In the early 1970s, Judd had the vision to transform a decommissioned army base in the town of Marfa, Texas, into a cultural nexus in the middle of nowhere. In the era of the Vietnam and Cold Wars, converting the former training grounds of the war machine was itself a work of art. The barracks, mess hall and artillery sheds are now an art center, with permanent galleries for Judd and several other artists who shared his philosophic sensibility.

A pilgrimage there takes one back to 1960s conceptualism. Oddly enough, given the chaotic emotions of that decade, the work is predominantly a form of order and sequence, its deliberateness distinctly removed from abstract expressionism, its stylistic predecessor. More crystalline than organic, it recalls the interest that Judd and other artists of this period had in geology, mineralogy and illumination. Yet even the name of The Chinati Foundation, dedicated to preserving this legacy of rationality, contains the seeds of the inexplicable: it comes from a nearby mountain range where mysterious, unexplained “Marfa Lights” flash across the desert floor.

Beside a field across from the artillery sheds, Judd created “15 untitled works in concrete,” a kilometer-long series of highly finished cement boxes. In an aerial view the crisply cast boxes look like cryptic symbols, a modernist linear Stonehenge aligned—as were the sky drawings of ancient astronomy—in axis with the Anasazi, Mayan, and Incan civilizations.

Judd said, “There are no believable new monuments,” yet these megalithic forms are certain monuments, mystical and militant, aimed straight at the Davis Mountains and the McDonald Observatory, where modern astronomers hunt the stars and search the fate of the universe.

At noon on January 27, 2003, I began walking the kilometer-long sequence of gray concrete walls and lintels. Under the blinding blue sky, the heated prairie landscape rendered all things small and bright. Objects began to hover. This transcendent state reminded me that artist Robert Smithson once observed that “the concealed surfaces inJudd’s work are hideouts for time. His art vanishes into a series of motionless intervals based on an order of solids.” This is evident in viewing Judd’s work. The “specific object” fades under a clinical repetition and a trance becomes the experience.

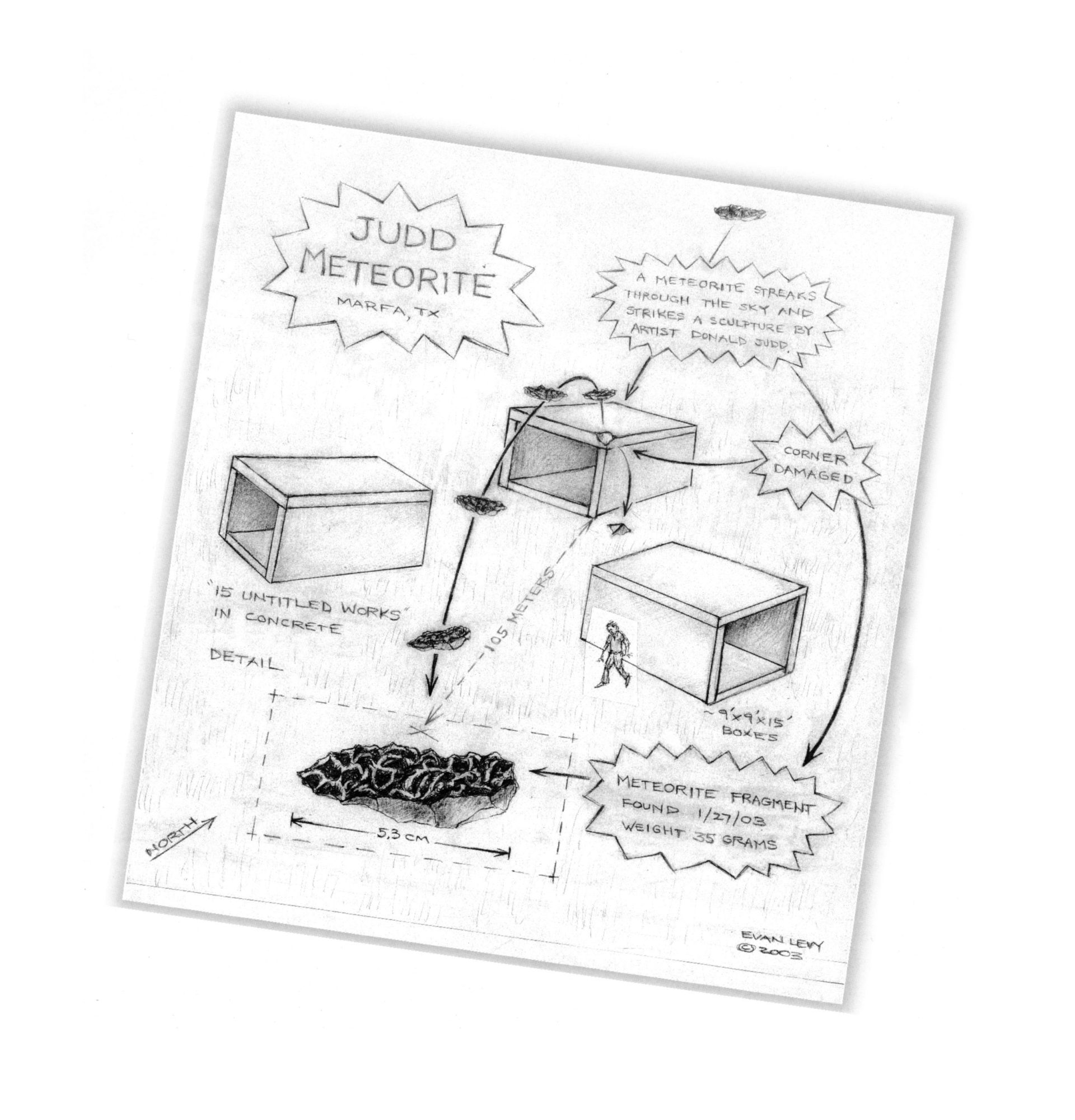

There is a flaw, a missing corner, in one of the concrete sculptures. In the face of such precision, the damage is a gaping wound of exposed aggregate. The tour guide explained it was struck by lightning last year. This explanation seems plausible, but there are no burn marks, and The Chinati Foundation refused to allow either photographs or further analysis of the damaged sculpture. Marfa is a place of superstition. Nothing is ever what it seems. Why hide what caused the damage? Was some aggrieved Marfan sniping at modern art?

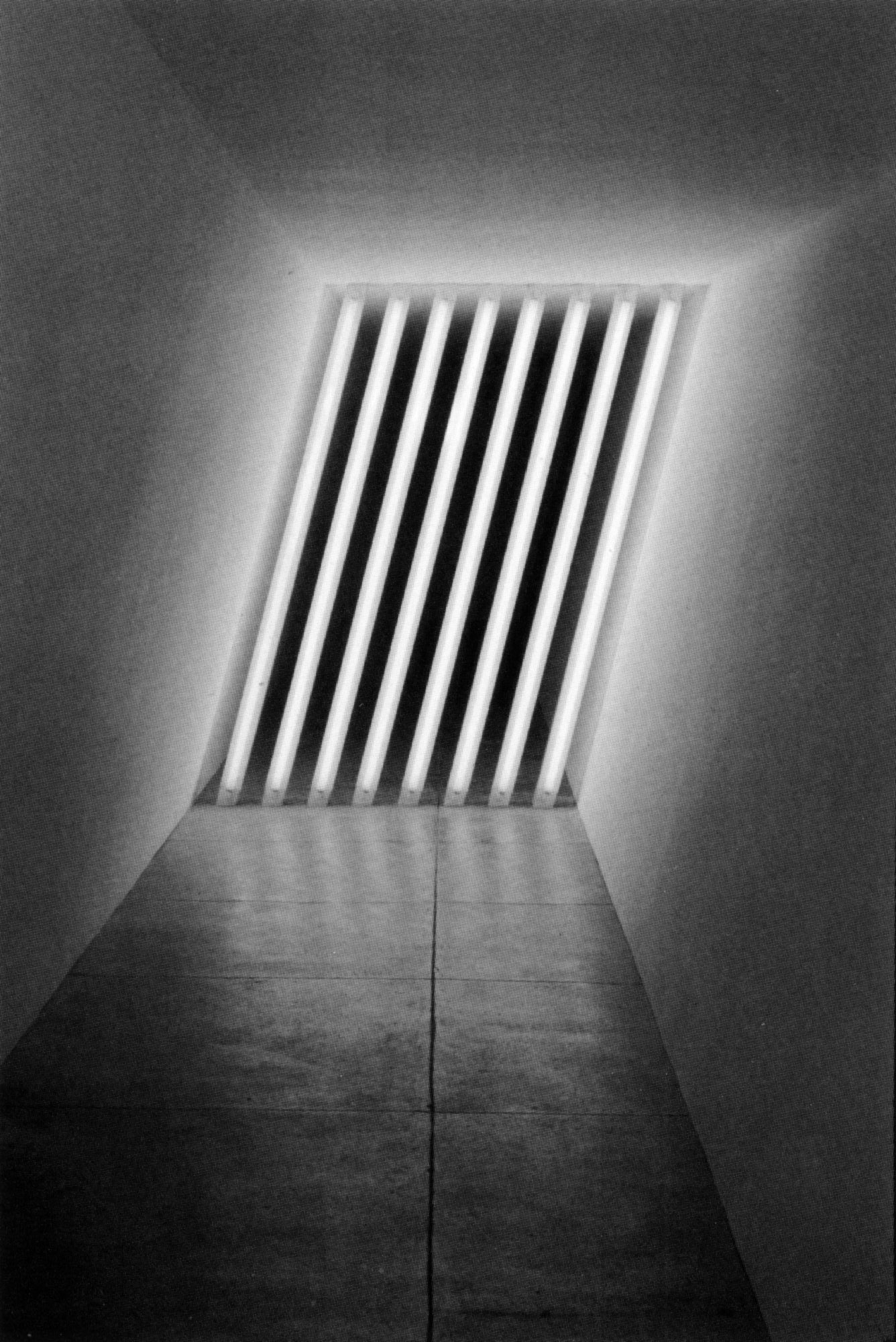

Dan Flavin, Untitled (Marfa Project), 1996, one of six buildings (permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas) [Photography by Florian Holzherr, 2001, ©2003 Judd Foundation]

The answer to this question seems to lie, though, not in the sky of southwest Texas but on its ground, a geologist’s nirvana called the Permian Basin, which is the heart of US oil production. Tens of thousands of years ago tectonic plates shifted and caused a collision of Earth’s crust that put the bend in the Rio Grande and spilled stones throughout the desert. These multicolored rocks now litter the dusty grounds of The Chinati Foundation.

While wandering in the field beside Judd’s sculptures, I picked up a strange, heavy black rock, very different than the myriad other-colored rocks in the vicinity. As it turns out, this rock is a meteorite, probably of a category called “achondrites.” More specifically, this meteorite seems to be an “angrite,” which isotopic studies have dated to four and a half billion years ago. Split and cracked from its molten reentry shell, the meteorite hit something hard and cleaved. The only objects in the vicinity are the concrete sculptures.

Donald Judd, 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982-1986 (permanent collection the Chinati Foundation, Marfa. Photograph by Florian Hokzherr, 2001 (c) 2003 Judd Foundation).

Did a meteorite damage the corner instead of lightning? The location of the strike and the trajectory make this possible. Scientific analysis would be required to determine absolutely, but to know such a thing is to settle only a part of the mystery and speculatively contemplate the beginnings of a Chinati myth. This rock might be the only known extraterrestrial object to have hit a work of modern art.

The Judd Meteorite is a ready-made of cosmological origin and perhaps a vandal. The path of this small stone forms an arc from the first conceptual artwork, namely the urinal that Marcel Duchamp directed into art history. Though not uncommon, meteorites are the rarest natural materials found on earth. Having marred a work of art makes this one even more rare. Judd questioned monument, and the cosmos questions Judd. He has been forced to posthumously confront his minimalist strivings for the “perfect surface” against, ironically, his own geological interest—a four-billion-year-old rock from another galaxy.

What can be expected of monument after the tragedy of September 11? The Western world is braced for disorder and poised for another man-inflicted disaster. To express this moment is to offer a response to the anxiety and fear in the population. Tense times require new approaches and activism. The artists of Judd’s generation distanced themselves from cultural centers to focus on the larger cosmos. Current artists seem confused about how to emerge from consumptive self-referential systems and move ideas beyond the art world.

Time ravages all displayed art. Nature vandalized this sculpture in a unique way, however, nicking this monument, this “specific object,” with a splinter of light. The Chinati Foundation should restrain from trying to re-create Judd’s perfect surface. Leave the damage—a flaw is a part of the myth. A meteorite was once a fallen star, and in superstition they bring a wish to Earth.

Lightning, concrete and meteorite become a small monument to the moment when the spirit was not damaged but reaffirmed.

An illustration by the author.