Memory & 1971 Journal

From “Memory” by Bernadette Mayer, Siglio, 2020 [courtesy Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego]

Share:

Time and its various essences lie at the heart of poet Bernadette Mayer’s Memory, an exhaustive and detailed project dedicated to the everyday. In July 1971, Mayer wrote daily in a journal and shot one roll of 35mm film for each day of the month. The writing feels adjacent to stream-of-consciousness, although it is more fragmented, more dedicated to the sounds words make and their rhythm against one another. An example from July 7: ”I thought that brush was my memory closer from behind, in the woods a gulf, a light crate for the phone, catch a car going by, waiting for them, get lost, pink toad, the thread of the restaurant, we eat.”

“Barbara gets up starts to sit on the car she rests one hand on paul’s knee she has one foot on the ground she sits on the car one knee bent with the foot up on the car one leg just hanging paul puts his arms around her waist her back against his chest she holds his two hands clasped at her waist with one of hers. Paul looks at me barbara looks away. So you know everything, everybody’s beauty, the whole of it & something changes: gp, a screen, dies & sleep says this: I would never set this up again. Paul looks at me barbara looks away”

From “Memory” by Bernadette Mayer, Siglio, 2020 [courtesy Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego]

What results is an additive incantation of life lived in New York City (and sometimes upstate), with everything that makes up an ordinary hot summer month. Photos accompanying the text are casual and sometimes unfocused, as if the act of taking them was more important than the result, with the text and the imagery often referring to each other.

On July 24, a series of images shows a man and woman in front of a car, embracing and laughing:

“Barbara gets up starts to sit on the car she rests one hand on paul’s knee she has one foot on the ground she sits on the car one knee bent with the foot up on the car one leg just hanging paul puts his arms around her waist her back against his chest she holds his two hands clasped at her waist with one of hers. Paul looks at me barbara looks away. So you know everything, everybody’s beauty, the whole of it & something changes: gp, a screen, dies & sleep says this: I would never set this up again. Paul looks at me barbara looks away”

From “Memory” by Bernadette Mayer, Siglio, 2020 [courtesy Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego]

Despite marking time and its vicissitudes, Memory is not at all a diary. Instead it reverberates with the same ethos as several conceptual projects of its time. In an effort to move away from the spirituality of abstract expressionism and the rigidity of formalist painting, artists in the late 1960s and early 1970s experimented with photography, drawing, performance, and video art. New approaches to various media allowed those artists to use facts, evidence, and data in an artistic refiguration of the experience of life. Lee Lozano, for instance, in her journal from 1969, recorded a series of dialogues she held with other artists and friends at her loft. The content of their conversation is not detailed; instead, she offers only sets of data—the names of those whom she sat with and the dates they met. Lozano and Mayer both often refer to “information,” a buzzword of the day that denies any kind of self-revelatory internal narrative. In fact, the only narrative in Mayer’s project comes from the days of the month, passing one after the other. Memory is less about recalling anything at all and instead acts as a kind of recapitulation of the ways in which memory works—information sure, but also hazy images and half-remembered truths.

Rosemary Mayer, Bernadette’s older sister, also kept a journal in 1971.

First printed in 2016, Excerpts from the 1971 Journal of Rosemary Mayer was edited by Mayer’s niece, Marie Warsh, and was published by Object Relations and SOUTHFIRST Gallery, which is located in Brooklyn and hosted an exhibition of her early work that same year.

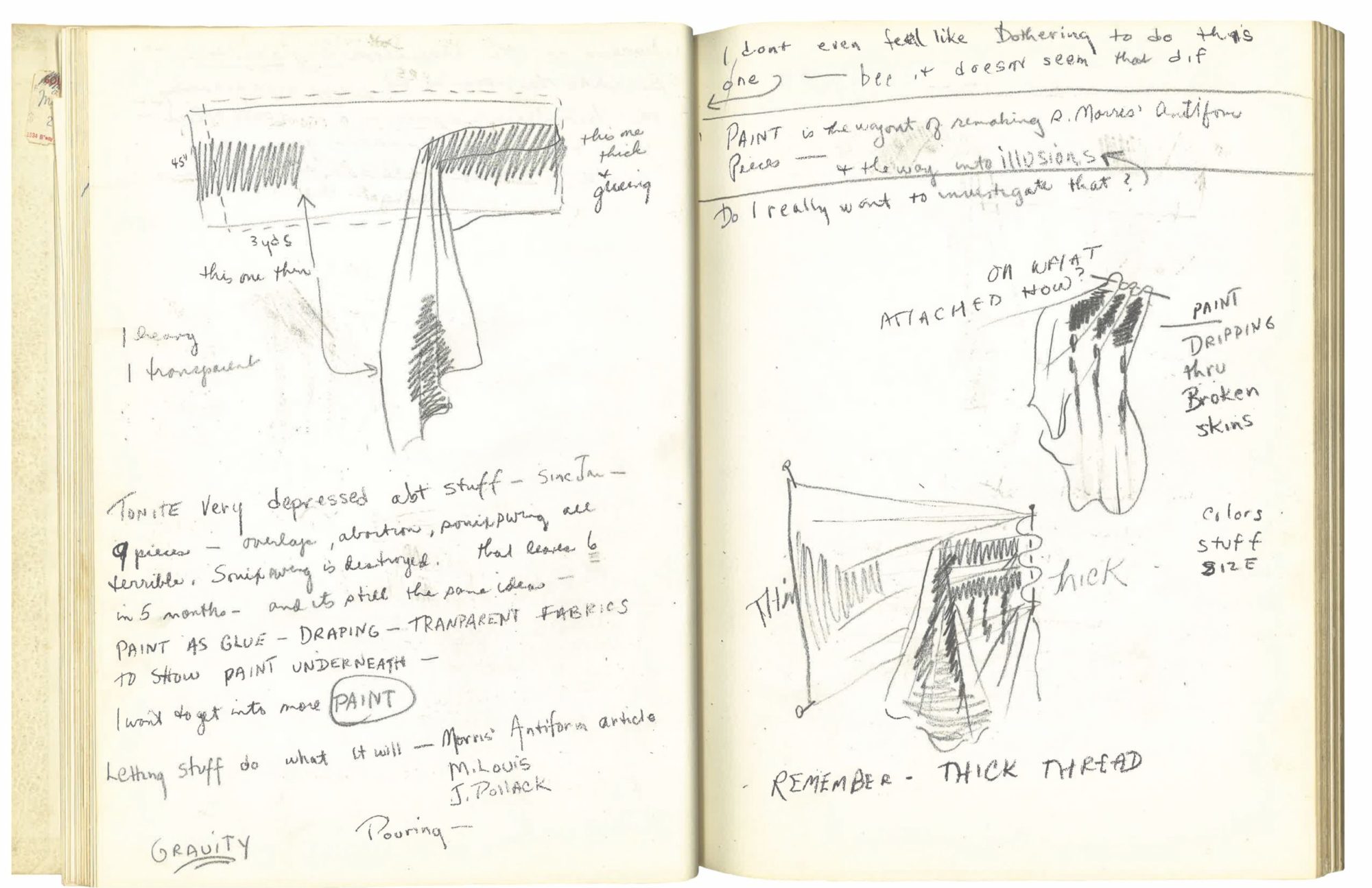

This gorgeous new edition, edited by Warsh and printed by Soberscove Press, includes more entries than the first edition, along with photos Rosemary took of her work, facsimiles of the journal entries, and several reproductions of her drawings.

New to this edition is an appendix listing all the books and authors Rosemary read that year, as well as the movies she viewed. The appendix in many ways encapsulates this project, as it so specifically locates Rosemary in a place and time.

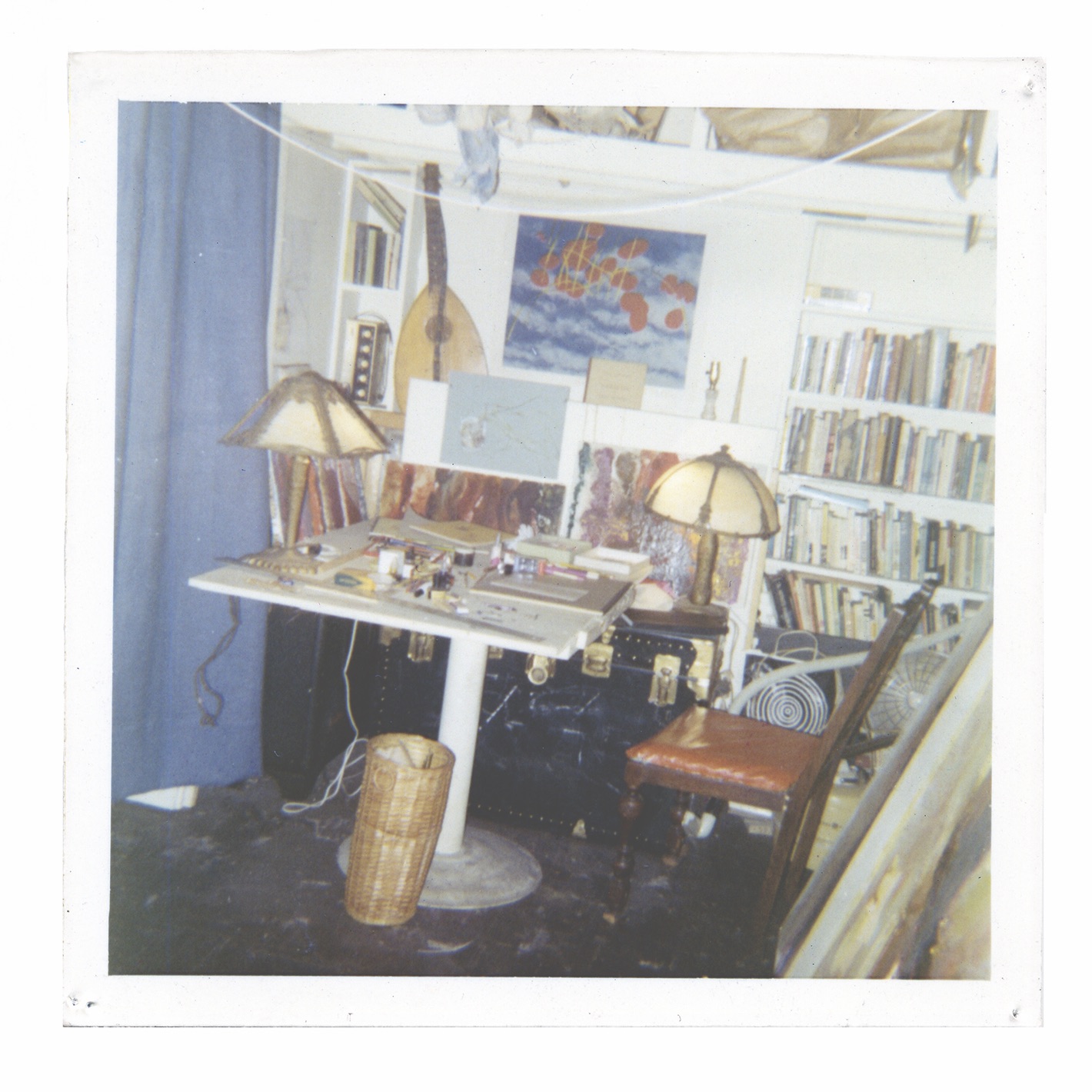

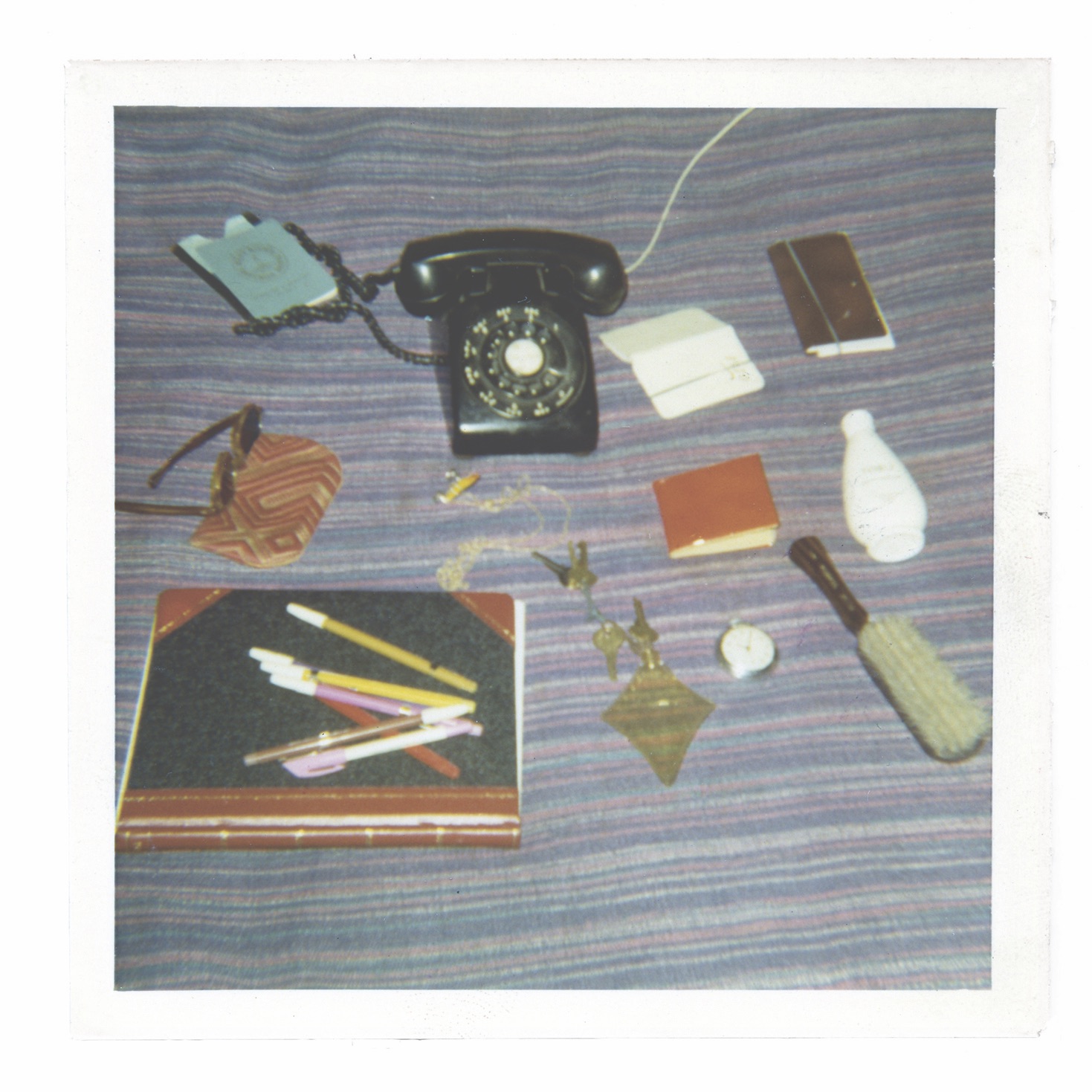

Rosemary Mayer, photographs of her apartment at 383 Broome Street, 1970 [courtesy of Soberscove Press]

Rosemary Mayer, photographs of her apartment at 383 Broome Street, 1970 [courtesy of Soberscove Press]

More straightforward than the text in Memory, these journal entries directly detail the inner life of a 28-year-old woman in 1971, living in New York, struggling with money, and creating new art through the draping of dyed fabrics.

Rosemary Mayer died in 2014, and her book feels like a posthumous project, a delving into personal life that could occur only after one has passed. Themes of love, loneliness, and a self-conscious desire for fame recur throughout the year.

She writes, on February 2: “Is it just Catholicism that makes it seem wrong to want to be famous—that’s not it though to be famous—it’s to be surer of myself & my work—I’m beginning to be one of those people who lives and breathes art.”

And on July 18: “I feel what I’m doing isn’t good enough to be important—that’s maybe what’s wrong. That I want it to be important so that I’ll be famous.”

Pages from the Journal of Rosemary Mayer, 1969-1971 [courtesy of Soberscove Press]

By charting her life through a year in vignettes that record daily thoughts and desires, Excerpts reads more like the development of an artist, rather than a build-up of impressions. Rosemary Mayer has only recently gained widespread recognition and, in this way, the text serves a larger purpose. It introduces the viewer to her thought processes and builds an archive for an artist who was dangerously close to being lost to time. Read together and in an age of pandemic, Memory and Excerpts feel like relief: living a life outside, amid friends, New York hustles, petty jealousies, and the everyday slog. What once we took for granted—the mundane, uneventful world—lives spectacularly in these texts. Lives lived. Lives remembered.

***

This feature originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Summer 2020 // Living & Working.