Marking Time: Willie Birch’s The Roofers

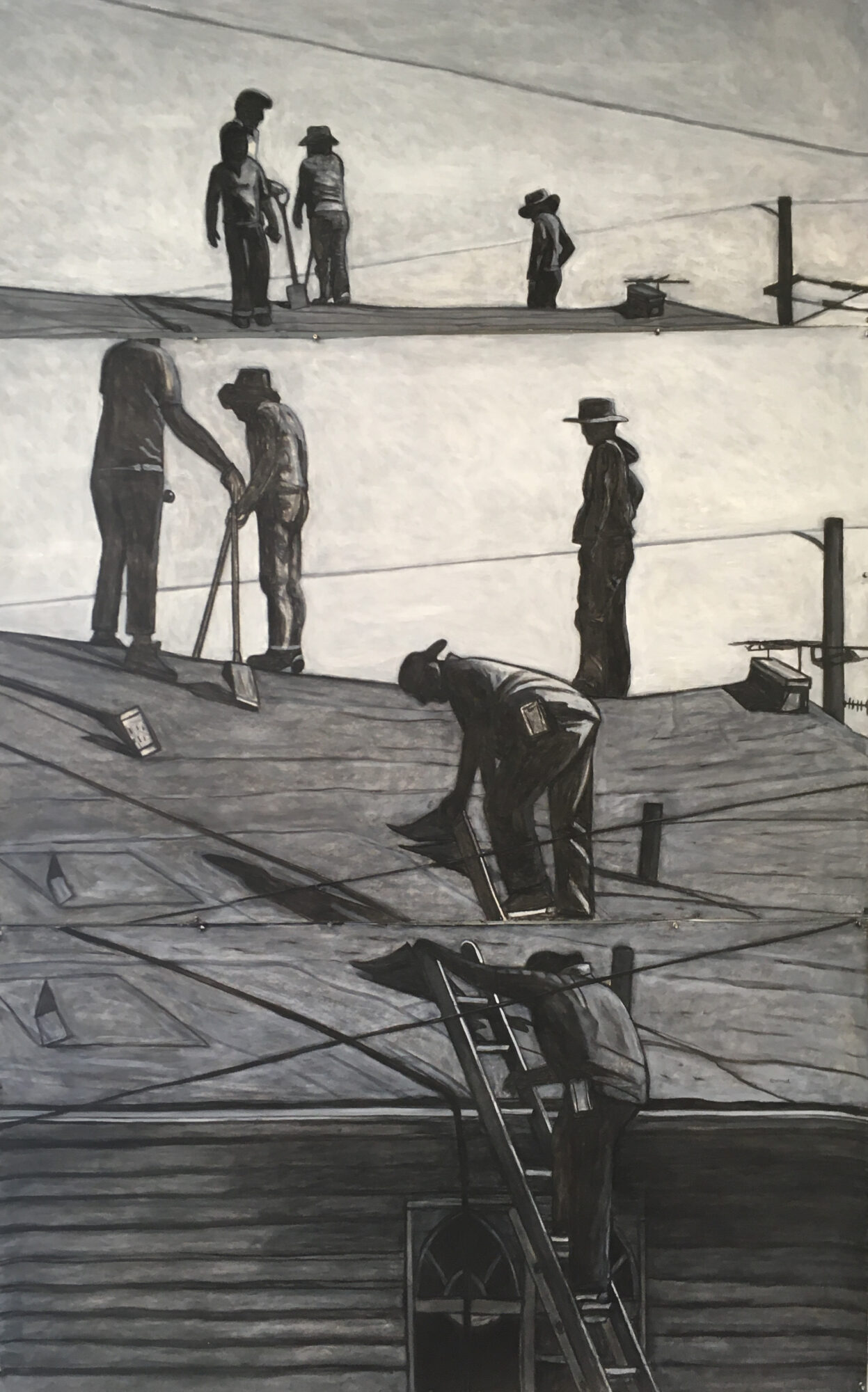

Willie Birch, The Roofers, 2022, triptych, 84 x 60 inches [© Willie Birch; courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Willie Birch, The Roofers, 2022, triptych, 84 x 60 inches [© Willie Birch; courtesy of the artist]

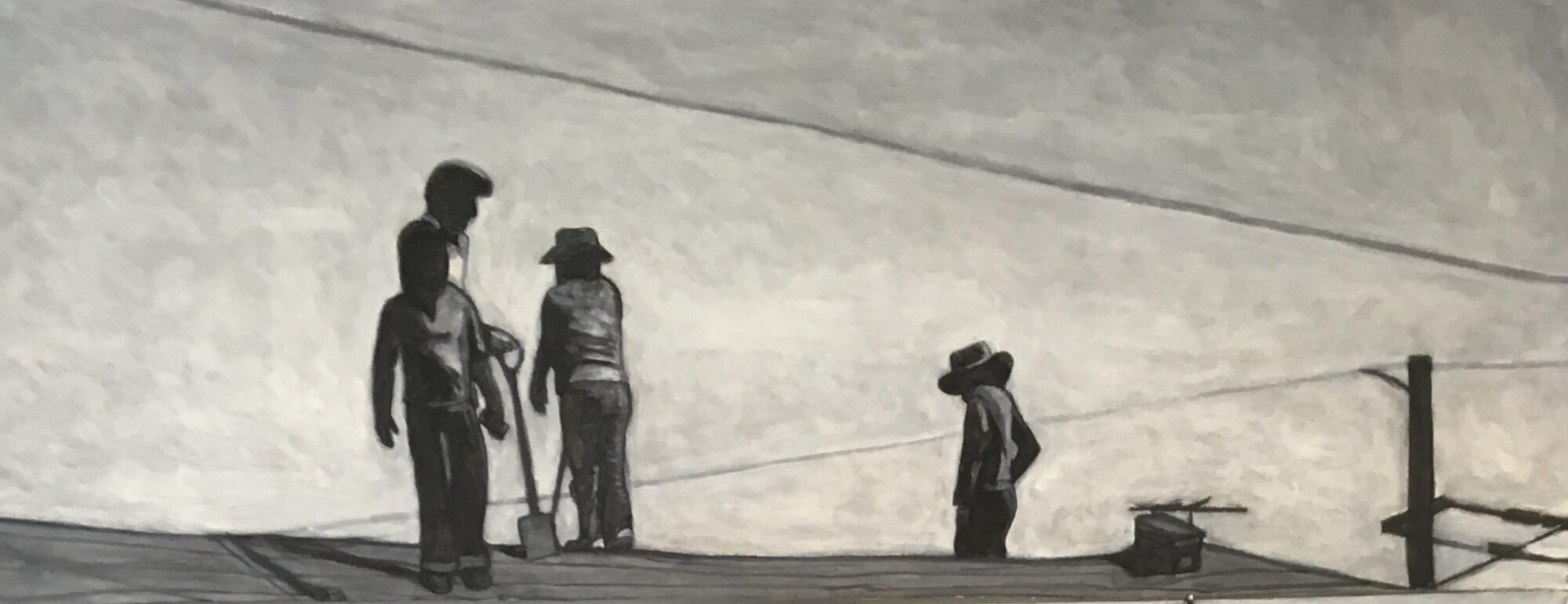

The figures in Willie Birch’s The Roofers (2022) mark time. I can’t get over their placement throughout the image. Tiered and presented as in a reenactment. My eyes go to a small figure wearing a wide-brimmed hat. Right elbow bent—their hand in a pocket or on a hip. There’s something in their bearing. They look to be contemplating—not how to lay roof tile but the very meaning of existence. What is life? I wondered for a long time if this figure were a double of the one to their left. The contemplative one is set apart from the other roofers, such that they appear at a diagonal, compositionally. During both studio visits that I had with the artist, I was preoccupied with this positioning. Eventually, I realized that within what was being depicted there was also a transposing of time. What the image shows is not simply a workday—the subject here—but a chronicling of time. Maybe a resituating of time is what the figure is dreaming about.

Birch erupts time. Part of how he achieves this effect is in how he uses line—on a diagonal. Implied and literal. Lines that feel corporeal themselves in the rendering of telephone cables, the configuration of roof shingles, ladder rungs, a windowpane, the siding of a house, and the shadowing of tools or limbs. All of which allows for a building up of space. An allusion to reassembling structure, reassembling space. The artist uses such meticulousness in positioning tile to pole to body, relative to the vastness of space. There is the labor of negating space—those who would negate our bodies in space. By marking time, the artist disrupts it. There are some things to stage: construction, mediation, meditation, and the quotidian. In how the figures are positioned (dispersed) throughout the frame, this scene could instigate the mnemonic or, in memory’s elusiveness, a predication (not prediction) of what’s to come.

Birch characterizes the work, made of charcoal and acrylic, as a painting. It is a painting impersonating a drawing. The graphic-ness of Birch’s mark tells me so. Also, the riveting holographic quality of each figure—how the eye and mind make sense of the shifting and relocating of bodies in this image. As if they were, indeed, doubling—the imitation game.

I want to place Birch next to Cauleen Smith for how Smith, in her work, “reflects on the everyday possibilities of the imagination.” And because of the artists’ projecting and retracing of objects—something Smith does in her installation Epistrophy. Also in how she sees “leaving one’s body as a kind of material technology” as being connected to the cosmos—what’s materializing on Birch’s persuasively transportive roof. I want to place Birch next to Chris Marker, as Marker tended to memory by collapsing time. Made time illusory, so that death, recollection, and futurity—wholly imagined—occupied the same gap. I want to place Birch next to William Kentridge, in that Kentridge accumulated time by erasing it. Every gesture removed, then reiterated on top of its previous flexion in Kentridge’s drawings to create bodies moving, thought forming.

Pivot your mind toward God. Deliberate loneliness, consternation, tragedy. Cue wrath. “The roofers” submit to a turning of the divine. Birch’s painting is larger than a tall person, measuring more than six feet. I find my small self at odds with how best to climb that roof. I try the ladder first. Then a harebrained scheme of propelling myself onto the roof from the rear of the image. Unseen, I think. The sequestered figure watches me struggle as I claw my way up. The air here is thick. I move, barely an inch, but my legs feel like stilts. I should’ve been a carpenter, really. It would have better prepared me for this.

Willie Birch, The Roofers, detail, 2022, triptych, 84 x 60 inches [© Willie Birch; courtesy of the artist]

I go to speak but my breath is hollowed out. My mouth is a small flap. I reach for one of the telephone cables. My arm, tabulated, hangs there for what feels like a day—six months—two eternities. But I did touch it. The telephone cable, the line, was thin as graphene but coarse. And knifed the sky. The ulterior motive—sky is a template, a map. One way of envisioning time. A quotidian marker of how to locate it. Inside this interval I pretend not to be stifled by time’s sky. I flatten to pick up one of the tools. And drop it. The roofing shovels, shingle eater, or magnetic sweeper remakes me into a grid. I am compliant. The objects embed me into more of the work. A figure on a ladder, climbing onto the roof, sprouts again a few paces up, as does part of the ladder, even as part of their leg seeps into the roofing—or grows out of it. I think about the activity as being more on a continuum of specific actions, specific tactics, rather than labor—work. I am truant in my claims. Spread out here, I feel the tensile strength of the workmanship. A culling of form, the massiveness of time’s incrementalism—put to work. The artist, as laborer, exposes linearity to be a farce. Space, here in the painting, is successive, dormant one minute, then made to plateau in the next.

Now I’m shadowing. It’s how I dwindle where planes intersect—a tract of roof masking the head of a figure, a whole scene, the sky doubling to keep tabs on time rematerializing as tarp or grip. Structure playing this thing out by magnifying and replicating the instantiable. Birch put line to memory. Put time to work. He put time to work by activating it. Now time can construe any delegation of form. The artist poses the question, through marking: What’s to become of time and our enduring of it?

Charcoal and paper hold every mark. Twice with the body. Three times. I’m a thumb bruised from rubbing. I am a piece of felt or tar paper being affixed. I wish I were a hatchet or a slater’s ax, a worn-out object. If only I could stay here, be the roof. A material possession to emulate. If I caved, it would be so that these figures, these bodies, could resist. Pooling here, I gather commentary on the blurriness of the image, which Birch created by mixing the charcoal with acrylic paint. I come to terms with the snapshot of a memory, with the feat of remembering in aggregate—as we do inside the business of living. I am your painting, someone says. Then, sometime later, I am membrane. I peek inside a window, staged precariously at the front of the image. The darkness lures me. Here seems to be the truth, to be what is a centering or outpouring of everything. To be what must come next in this turning of the divine, in marking. It isn’t me—I am plastic shearing.

Willie Birch, The Roofers, detail, 2022, triptych, 84 x 60 inches [© Willie Birch; courtesy of the artist]

Sherae Rimpsey is an artist and writer. Rimpsey is the Mildred Thompson Art Writing and Editorial Fellow.

The Mildred Thompson Arts Writing and Editorial Fellowship is a collaboration between Art Papers and Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University. Funding for the two-year editorial position was provided to Newcomb Art Museum by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for an emerging Black arts writer/editor to gain hands-on experience as part of Art Papers’ editorial team. The fellowship also honors and builds upon the legacy of Mildred Thompson, associate editor of ART PAPERS from 1989 to 1997.

Conceptualized as part of Art Papers’ Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility efforts, the fellowship received seed funding from AEC Trust and The Homestead Foundation to pilot the program in 2022.