Interview: Marcia Tucker

Image of New Museum staff. Featured left to right is Lynn Gumpert, Charles Sitzer, Robin Dodds, Marcia Tucker, Joanne Brockley, and John Jacobs, 1981, [photo: Bonnie Johnson; courtesy of New Museum, New York]

"I set out to make a situation that would subvert my own taste; I'm bored by my own taste."

Share:

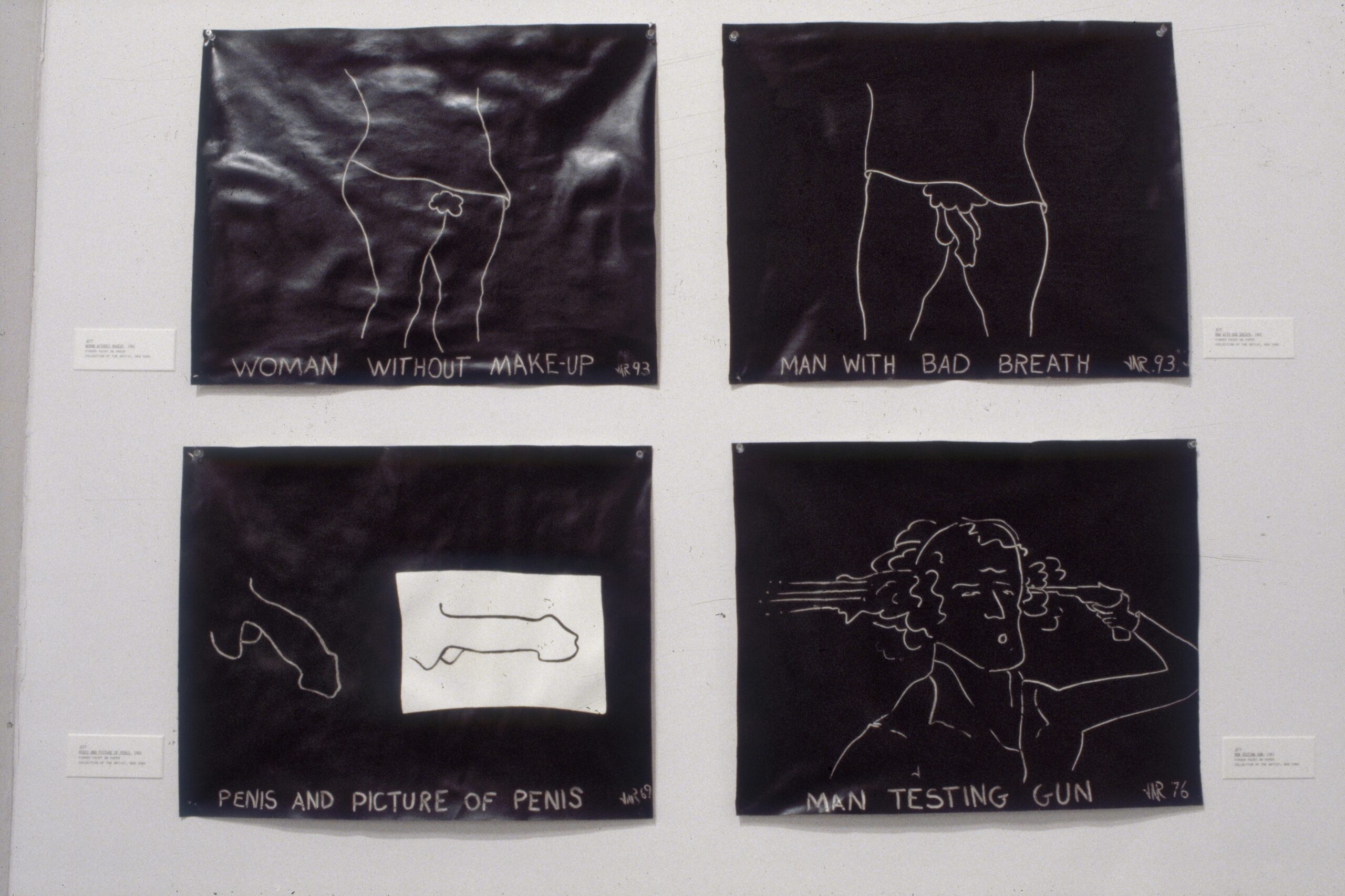

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS January/February 1982, Vol 6, Issue 1. Photos included in this interview are images from throughout the New Museum’s beginnings and an exhibition titled Not Just For Laughs: The Art of Subversion.

As founder and director of The New Museum, Marcia Tucker has not only established an unique, experimental institution devoted to contemporary art, but has also been and continues to be one of the most influential curators in the art world today.

As a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Tucker presented controversial exhibits by such artists as Robert Morris (1970), James Rosenquist (1972), Bruce Nauman (1973), Lee Krasner (1973-74), and Richard Tuttle (1975). With the New Museum, Tucker’s influence has continued to grow. Her exhibit, “Bad Painting,” in 1978, presented issues which continue to be hotly debated in the current art scene.

In 1981, Tucker curated the prestigious New Orleans Museum of Art and traveled throughout the Southeast to visit artists’ studios. She has always been strongly committed to considering and presenting the work of artists living outside New York.

Following her October lecture at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Marcia Tucker was interviewed by Julia A. Fenton.

Julia Fenton: After you were fired from the Whitney in 1976, you founded and developed the New Museum as a major facility for contemporary art. How did you decide to do that?

Marcia Tucker: I actually didn’t make that decision after being fired. I had worked for many years at the Whitney for Jack Bauer in what was close to ideal situation. At least three years prior to 1976, I began to play around with the idea of how a museum could function for artists, especially in relation to contemporary art, without some of the drawbacks that a large-scale museum and its bureaucracy entail. I developed a plan for an organization that I jokingly called the “Museum in the Sky”, in the assumption that one day it would get off the ground. I had almost all the plans for The New Museum written down and had discussed them with a number of artists and colleagues long before I left. When Bauer left the Whitney, a new director came in with a new set of priorities; I represented another set of priorities.

In 1976, I traveled in the Pacific Northwest looking at art. I met Anne Focke who had just founded “And/Or”, and Burke Walker who had just founded an alternative theater company called “The Empty Space”. Although they were very poor at that time, they were very involved in what they were doing and very optimistic about their work. I was depressed at that time because I knew things weren’t going well at the Whitney; I couldn’t see any solution for myself other than changing jobs and ultimately finding myself back in a similar situation. Somehow, being around Anne and Burke for that week changed my attitude. When I came back to New York and got fired (although I must say I hadn’t expected that), the plans I had for the New Museum suddenly seemed realizable.

The first thing I did was call a lawyer. Lawyers are very direct; if you ask them how to do something, they tell you. They don’t talk about feasibility. Most other people I spoke to said, “It’s a great idea, but you can’t do it.” (I’ve spent a lot of time hearing people tell me, “You can’t do that.”)

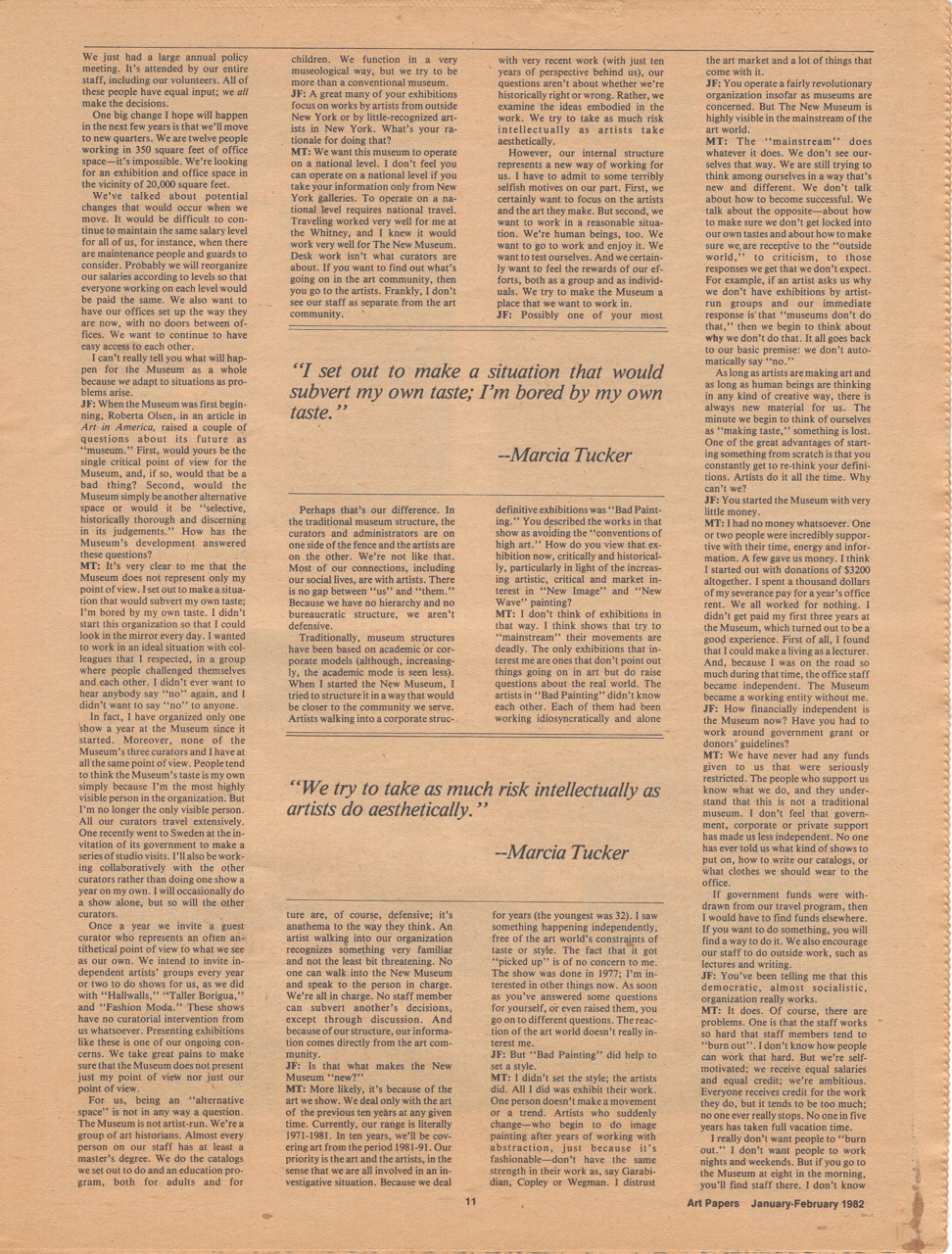

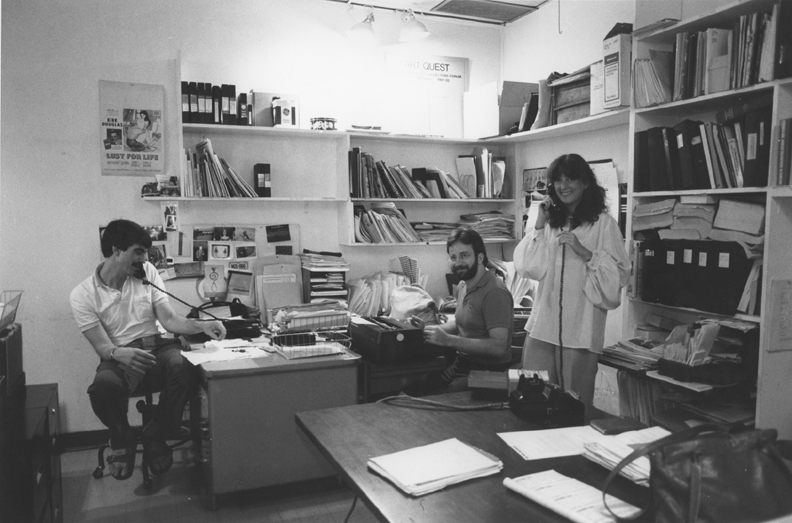

Marcia Tucker (right), John Jacobs (left), and Ned Rifkin (center) at the New Museum offices in the New School, 1982 [courtesy of New Museum, New York]

JF: How was the Museum developed in the last five years? Is it different from your original idea of it?

MT: First, it became very clear that our primary concern would be with the exhibitions and catalogs. In order to do those, we had to have a very systematic program of travel. We were, and are, interested in providing a very solid body of critical material that also addresses itself to the general public.

JF: How do these programs fit into the more traditional, art historical scheme of things?

MT: We show very recent work. We don’t know what’s going to become famous and what’s going to lapse into obscurity. The most important and interesting art work, for me, is work that generates ideas. I feel those ideas should be dealt with in a permanent published form. Exhibitions are, after all, temporary.

You asked about my original intentions. I’ve found that one can put things on paper that people simply can’t do. For example, I used to think it would be wonderful to have one curator traveling all over the country for six months out of the year. But curators are people who have families and need contact with their homes.

The main thing I intended for The New Museum was to make it a collaborative organization. I’ve done that. Therefore, its continuing development is out of my hands. The direction the Museum takes is a function of the interests and needs of our staff, and those interests and needs change. If the Museum had continued in the direction I originally conceived for it, it would have represented only my interests. This institution continues to be interesting to all the staff because all of us have an essential say in its policy and direction.

JF: Has the democratic nature of the Museum caused any problems?

MT: It’s gotten better, if anything. I’m no longer in the situation of training people. Almost everyone on our current staff is over 30; everyone is an experienced professional. We are colleagues working together. We’ve just started a series of regular staff meetings which are run in turn by each of us. I admit to being the person who may set up such initial situations, but I don’t do so arbitrarily. I have suggestions, but so do others on the staff.

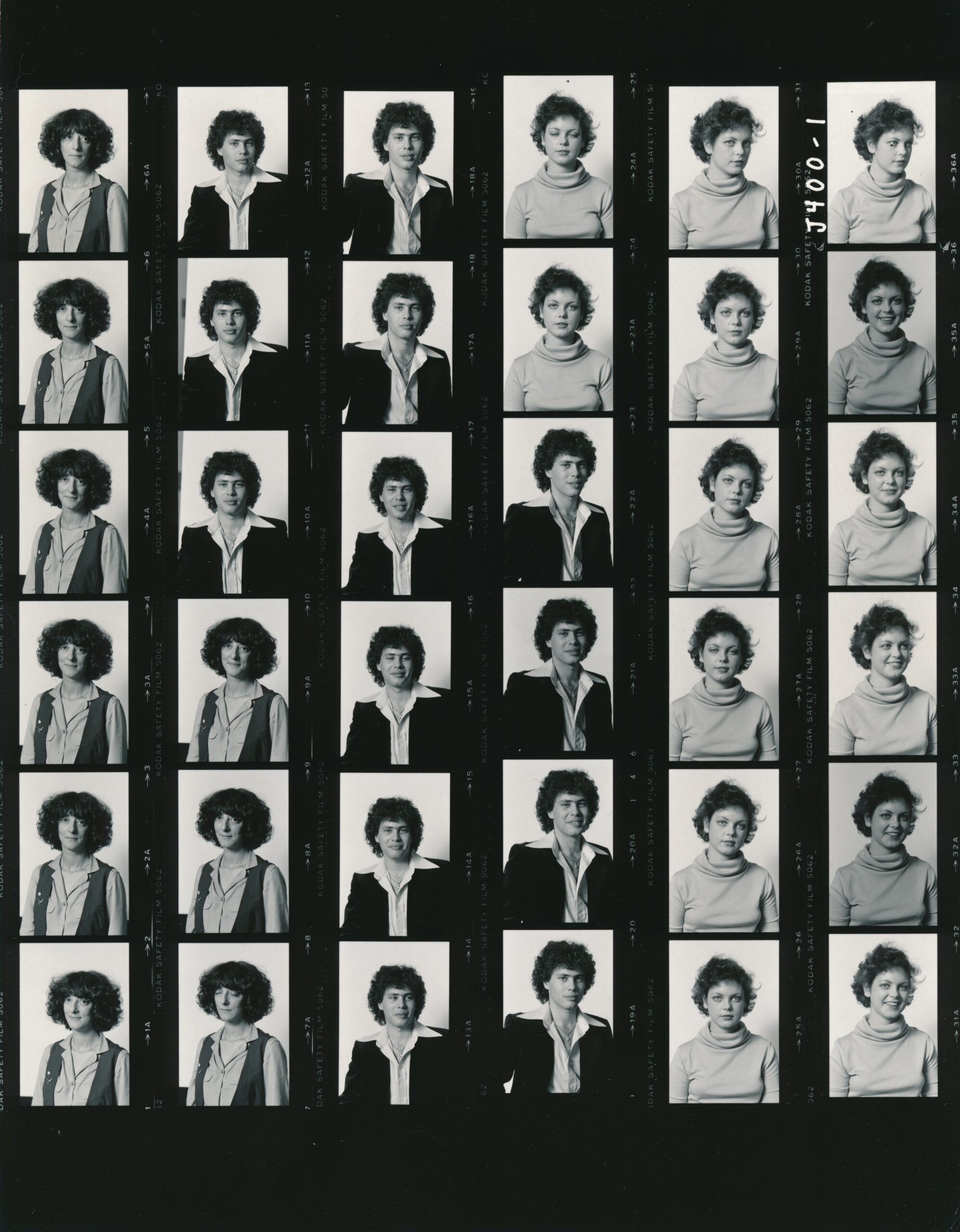

Contact sheet, New Museum of Contemporary Art staff portraits, 1978 [courtesy of New Museum, New York]

JF: What direction do you see the Museum taking in the future?

MT: Part of the Museum’s success is due to its flexibility, its ability to adapt to different needs at different times. We just had a large annual policy meeting. It’s attended by our entire staff, including our volunteers. All of these people have equal input; we all make the decisions.

One big change I hope will happen in the next few years is that we’ll move to new quarters. We are twelve people working in 350 square feet of office space–it’s impossible. We’re looking for an exhibition and office space in the vicinity of 20,000 square feet.

We’ve talked about potential changes that would occur when we move. It would be difficult to continue to maintain the same salary level for all of us, for instance, when there are maintenance people and guards to consider. Probably we will reorganize our salaries according to levels so that everyone working on each level would be paid the same. We also want to have our offices set up the way they are now, with no doors between offices. We want to continue to have easy access to each other.

I can’t really tell you what will happen for the Museum as a whole because we adapt to situations as problems arise.

JF: When the Museum was first beginning, Roberta Olsen, in an article in Art in America, raised a couple of questions about its future as “museum”. First, would yours be the single critical point of view for the Museum, and, if so, would that be a bad thing? Second, would the Museum simply be another alternative space or would it be “selective, historically thorough and discerning in its judgments.” How has the Museum’s development answered these questions?

MT: It’s very clear to me that the Museum does not represent only my point of view. I set out to make a situation that would subvert my own taste; I’m bored by my own taste. I didn’t start this organization so that I could look in the mirror every day. I wanted to work in an ideal situation with colleagues that I respected, in a group where people challenged themselves and each other. I didn’t ever want to hear anybody say “no” again, and I didn’t want to say “no” to anyone.

In fact, I have organized only one show a year at the Museum since it started. Moreover, none of the Museum’s three curators and I have at all the same point of view. People tend to think the Museum’s taste is my own simply because I’m the most highly visible person in the organization. But I’m no longer the only visible person. All our curators travel extensively. One recently went to Sweden at the invitation of its government to make a series of studio visits. I’ll also be working collaboratively with the other curators rather than doing one show a year on my own. I will occasionally do a show alone, but so will the other curators.

Once a year we invite a guest curator who represents an often antithetical point of view to what we see as our own. We intend to invite independent artists’ groups every year or two to do shows for us as we did with “Hallwalls,” “Taller Borigua” and “Fashion Moda.” These shows have no curatorial intervention from us whatsoever. Presenting exhibitions like these is one of our ongoing concerns. We take great pains to make sure that the Museum does not present just my point of view nor just our point of view.

For us, being an “alternative space” is not in any way a question. The Museum is not artist-run. We’re a group of art historians. Almost every person on our staff has at least a master’s degree. We do the catalogs we set out to do and an education program, both for adults and for children. We function in a very museological way, but we try to be more than a conventional museum.

JF: A great many of your exhibitions focus on works by artists from outside New York or by little-recognized artists in New York. What’s your rationale for doing that?

MT: We want this museum to operate on a national level. I don’t feel you can operate on a national level if you take your information only from New York galleries. To operate on a national level requires national travel. Traveling worked very well for The New Museum. Desk work isn’t what curators are about. If you want to find out what’s going on in the art community, then you go to the artists. Frankly, I don’t see our staff as separate from the art community.

Perhaps that’s our difference. In the traditional museum structure, the curators and administrators are on one side of the fence and the artists are on the other. We’re not like that. Most of our connections, including our social lives, are with artists. There is no gap between “us” and “them.” Because we have no hierarchy and no bureaucratic structure, we aren’t defensive.

Traditionally, museum structures have been based on academic or corporate models (although, increasingly, the academic mode is seen less). When I started the New Museum, I tried to structure it in a way that would be closer to the community we serve. Artists walking into a corporate structure are, of course, defensive; it’s anathema to the way they think. An artist walking into our organization recognizes something very familiar and not the least bit threatening. No one can walk into the New Museum and speak to the person in charge. We’re all in charge. No staff member can subvert another’s decisions, except through discussion. And because of our structure, our information comes directly from the art community.

JF: Is that what makes the New Museum “new?”

Robert Colescott, George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook, 1975, 78.5 in x 98.25 in [courtesy of the artist and New Museum, New York]

Jeff, Not Just For Laughs: The Art of Subversion, 1981, installation view [courtesy of New Museum, New York]

MT: More likely, it’s because of the art we show. We deal only with the art of the previous ten years at any given time. Currently, our range is literally 1971-1981. In ten years, we’ll be covering art from the period 1981-91. Our priority is the art and the artists, in the sense that we are all involved in an investigative situation. Because we deal with very recent work (with just ten years of perspective behind us), our questions aren’t about whether we’re historically right or wrong. Rather, we examine the ideas embodied in the work. We try to take as much risk intellectually as artists take aesthetically.

However, our internal structure represents a new way of working for us. I have to admit to some terribly selfish motives on our part. First, we certainly want to focus on the artists and the art they make. But second, we want to go to work and enjoy it. We want to test ourselves. And we certainly want to feel the rewards of our efforts, both as a group and as individuals. We try to make the Museum a place that we want to work in.

JF: Possibly one of your most definitive exhibitions was “Bad Painting.” You described the works in that show as avoiding the “conventions of high art.” How do you view that exhibition now, critically and historically, particularly in light of the increasing artistic, critical and market interest in “New Image” and “New Wave” painting?

MT: I don’t think of exhibitions in that way. I think shows that try to “mainstream” their movements are deadly. The only exhibitions that interest me are ones that don’t point out things going on in art but do raise questions about the real world. The artists in “Bad Painting” didn’t know each other. Each of them had been working idiosyncratically and alone for years (the youngest was 32). I saw something happen independently, free of the art world’s constraints of taste or style. The fact that it got “picked up” is of no concern to me. The show was done in 1977; I’m interested in other things now. As soon as you’ve answered some questions for yourself, or even raised them, you go on to different questions. The reaction of the art world doesn’t really interest me.

JF: But “Bad Painting” did help to set a style.

MT: I didn’t set the style; the artists did. All I did was exhibit their work. One person doesn’t make a movement or a trend. Artists who suddenly change–who begin to do image painting after years of working with abstraction, just because it’s fashionable–don’t have the same strength in their work as, say Garabidian, Copley or Wegman. I distrust the art market and a lot of things that come with it.

JF: You operate a fairly revolutionary organization insofar as museums are concerned. But The New Museum is highly visible in the mainstream of the art world.

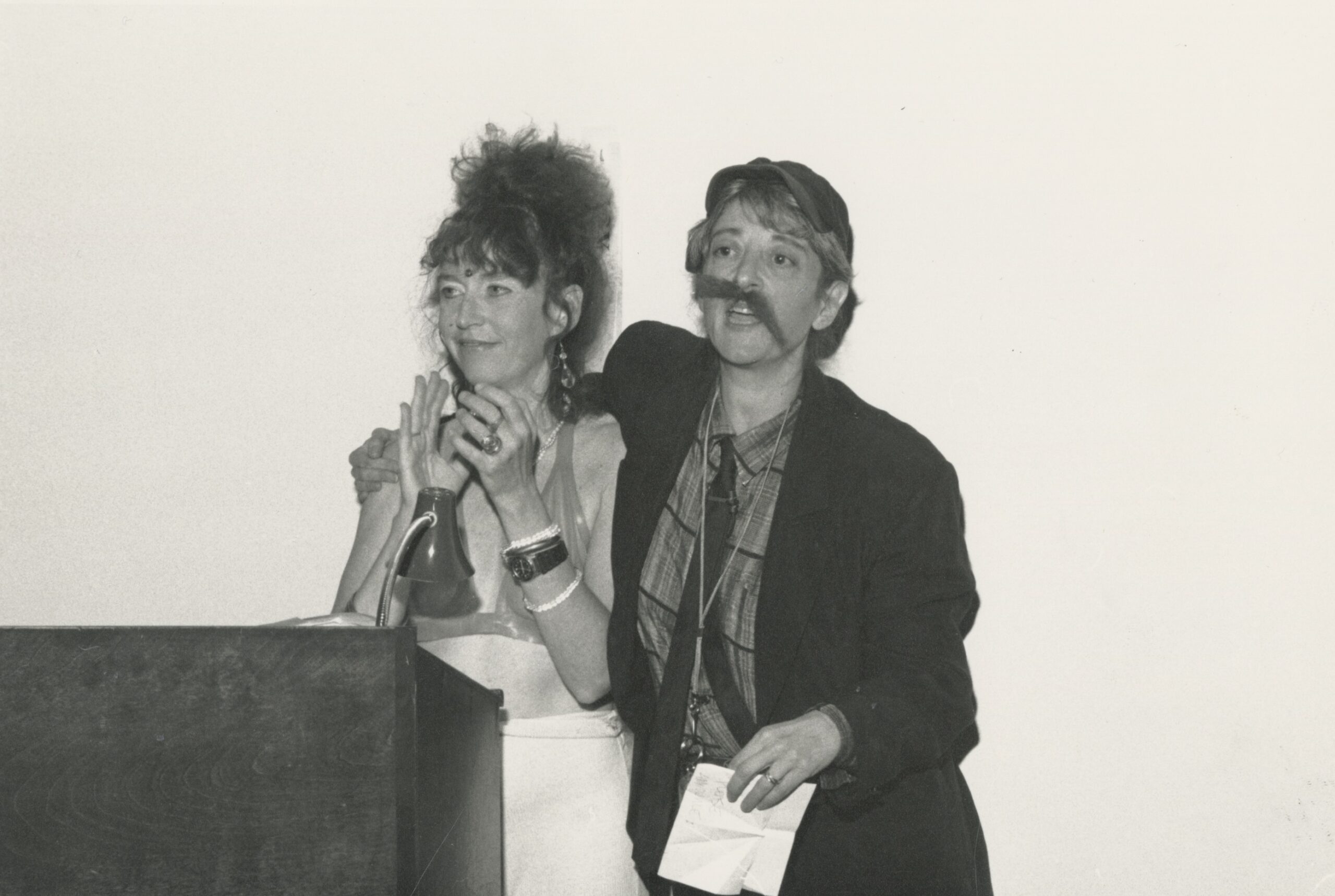

Linda Montano (left), and Marcia Tucker during Linda’s Last Performance, 1991 [courtesy of New Museum, New York]

MT: The “mainstream” does whatever it does. We don’t see ourselves that way. We are still trying to think among ourselves in a way that’s new and different. We don’t talk about how to become successful. We talk about the opposite–about how to make sure we don’t get locked into our own tastes and about how to make sure we are receptive to the “outside world,” to criticism, to those responses we get that we don’t expect. For example, if an artist asks us why we don’t have exhibitions by artist-run groups and our immediate response is that “museums don’t do that,” then we begin to think about why we don’t do that. It all goes back to our basic premise: we don’t automatically say “no.”

As long as artists are making art and as long as human beings are thinking in any kind of creative way, there is always new material for us. The minute we begin to think of ourselves as “making taste,” something is lost. One of the great advantages of starting something from scratch is that you constantly get to re-think your definitions. Artists do it all the time. Why can’t we?

JF: You started the Museum with very little money.

MT: I had no money whatsoever. One or two people were incredibly supportive with their time, energy and information. A few gave us money. I think it started out with donations of $3200 altogether. I spent a thousand dollars of my severance pay for a year’s office rent. We all worked for nothing. I didn’t get paid my first three years at the Museum, which turned out to be a good experience. First of all, I found that I could make a living as a lecturer. And, because I was on the road so much during that time, the office staff became independent. The Museum became a working entity without me.

JF: How financially independent is the Museum now? Have you had to work around government grant or donors’ guidelines?

MT: We have never had any funds given to us that we seriously restricted. The people who support us know what we do, and they understand that this is not a traditional museum. I don’t feel that government, corporate or private support has made us less independent. No one has ever told us what kind of shows to put on, how to write our catalogs, or what clothes we should wear to the office.

If government funds were withdrawn from our travel program, then I would have to find funds elsewhere. If you want to do something, you will find a way to do it. We also encourage our staff to do outside work, such as lectures and writing.

JF: You’ve been telling me that this democratic, almost socialistic, organization really works.

MT: It does. Of course, there are problems. One is that the staff works so hard that staff members tend to “burn out”. I don’t know how people can work that hard. But we’re self-motivated; we receive equal salaries and equal credit; we’re ambitious. Everyone receives credit for the work they do, but it tends to be too much; no one ever really stops. No one in five years has taken full vacation time.

I really don’t want people to “burn out.” I don’t want people to work nights and weekends. But if you go to the Museum at eight in the morning, you’ll find staff there. I don’t know how to generate a support staff that just does the dirty work; the very concept of the Museum requires that dirty work be shared. I thought I worked as hard at the Whitney as any human could. It was a vacation compared to now.

We also depend very much on each other. We all edit each other, work in teams and support each other. If one person is out, the rest of us move in to cover the gap. When something isn’t going right, there is no “boss” to go to. You go to the group, and the group comes up with a solution to try out. The reason people have been skeptical about how our organization works is that they have never tried it. It does work.

Marcia Tucker, Allan Schwartzman, A.C. Bryson, Susan Logan, Michiko Miyamoto, 1977, [photo: Warren Silverman; courtesy of New Museum, New York]

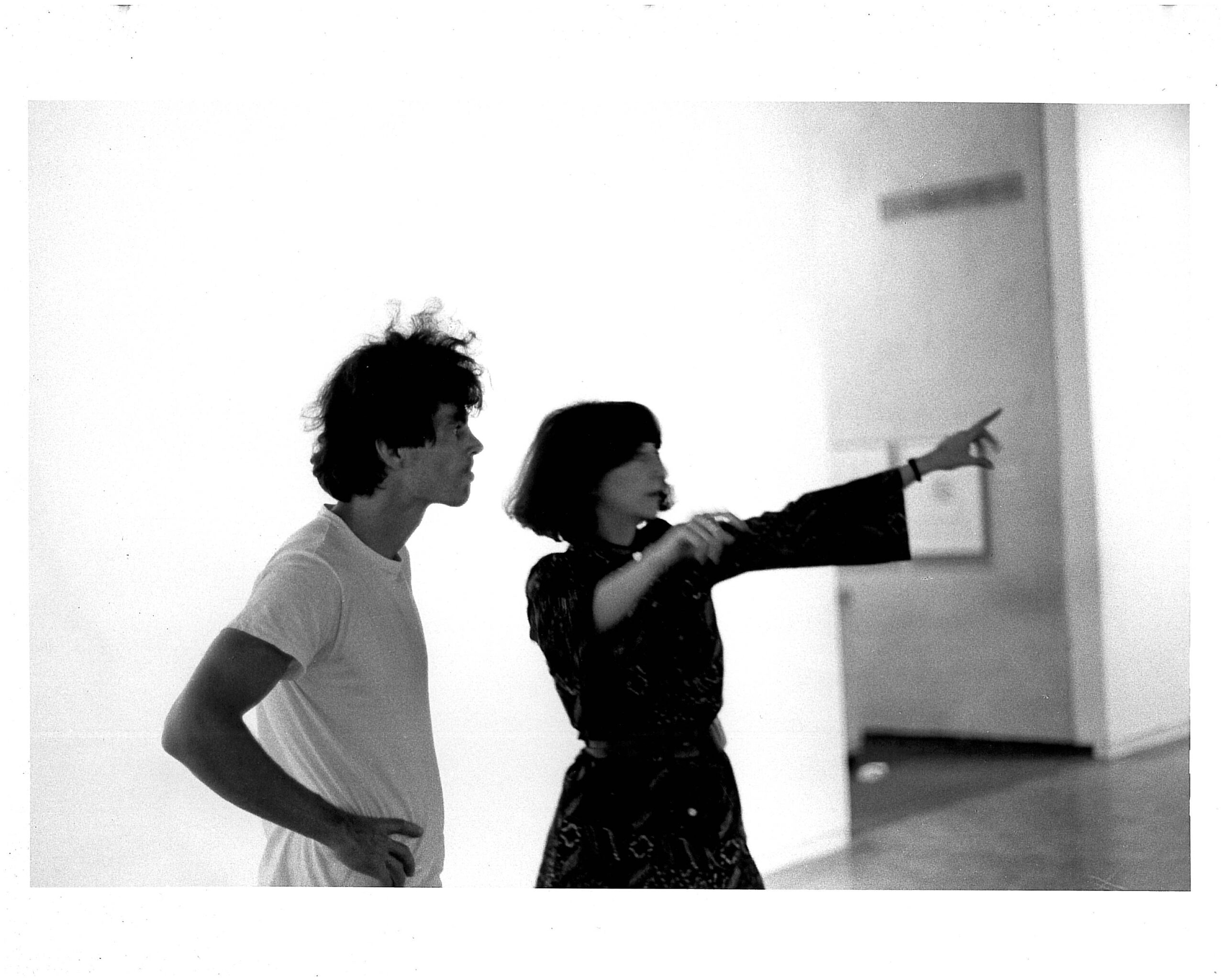

Marcia Tucker with artist Richard Tuttle, 1975 [photo: Roni Feinstein; courtesy of New Museum, New York]

JF: In a 1976 interview in ArtNews, while you were still at the Whitney, you said you didn’t want to be a politician or policy maker—that it was important for you to have no ulterior motive when you looked at art. But now that you are a “director,” not a “curator,” how do you maintain your admitted strong, personal interest in artists and their work?

MT: I can’t do it all the time. And I don’t want to undermine our curatorial staff. We have three extremely competent curators; I have to accept that situation in the way any other museum director should. I want to treat our curators in the way I would like to have been treated. That means I don’t interfere with them.

I’m not, however, completely divorced from art and artists. It doesn’t matter that I am a director. All my friends are still artists, and I can spend time with whomever I want. And although I did not make this trip to Atlanta to visit artists’ studios, one of our curators recently did just that. However, I still go to studios; I still look; my eyes still function. My current position doesn’t feel any different than it ever did, except that I do fewer shows and more fundraising. I’ve also re-adjusted some of my personal priorities so that I can have more time with my friends. One’s entire life doesn’t have to be self-conscious. The only difference is that I can’t look at art full-time and that I don’t go on the road looking at art.

On the other hand, I really enjoy fundraising. I enjoy the administrative problems, because they are not the usual ones. I’m fundraising for and directing an organization I absolutely believe in. It represents a genuine alternative for me. And the people who give us money understand what we are doing and believe in it, even though they’re not all involved with the kind of work we present. A number of our trustees are there to learn more about contemporary art, to change the way they think.

JF: In your talk last night, you spoke of “idea,” “paradox,” “metaphor,” “frustration,” “layering of meanings,” and “subversion” as methods for challenging systems of thought and about artists who work with conceptual and psychological dichotomies. There is a strong concern that comes through all the work you show. Those artists are on the edge of something.

MT: Yes. I think they are on the edge of society in a way.

JF: Is that, then, a role of artists—to change society?

MT: All of this is highly speculative—I’m not pointing to anything. But there are things that have changed of which the general public isn’t cognizant. Those changes take place in private, and at least we have access to studios where those ideas happen.

JF: How do you view your role in this?

MT: Actually when I take a “busman’s holiday,” I go look at early Flemish paintings. I am indeed interested in the past, and I think it’s only through the past that one really understands the present. I was, after all, an art historian.

I’m not interested in being an arbiter of taste because that’s self-defeating. It takes many generations to find out which artists of today made it through. By that time, all of us will be dead. The point is to try to grapple with the larger issues—that is, to try to understand the world we live in and what our position is in it, to try to understand who we are, how we see ourselves and how we see others. I’m not interested in the rest.

When I see some really innovative work, I try to spend some time with it. I don’t pick up on work because I think it’s a certain thing, a “right” style. And I don’t believe my taste has to be consistent. It’s not that you ask a question and then find the work that fits it. The work itself raises questions. And the questions are always connected in some way with your own life, whether or not you know it.

JF: Is that the point of view objective?

MT: There is no such thing as “objective.” I don’t view work as someone separate from who I am. No art historian, no human being can be disconnected from their work in that way. Marxist art historians are already dealing with that issue. They’ve said they resent the art historical, objective, disenfranchised voice—that every one of us has a stake in our work and that we should acknowledge it. Obviously, there must be something in me, as a person, that responds to certain kinds of work.

JF: The next exhibition you’ve organized for the New Museum…

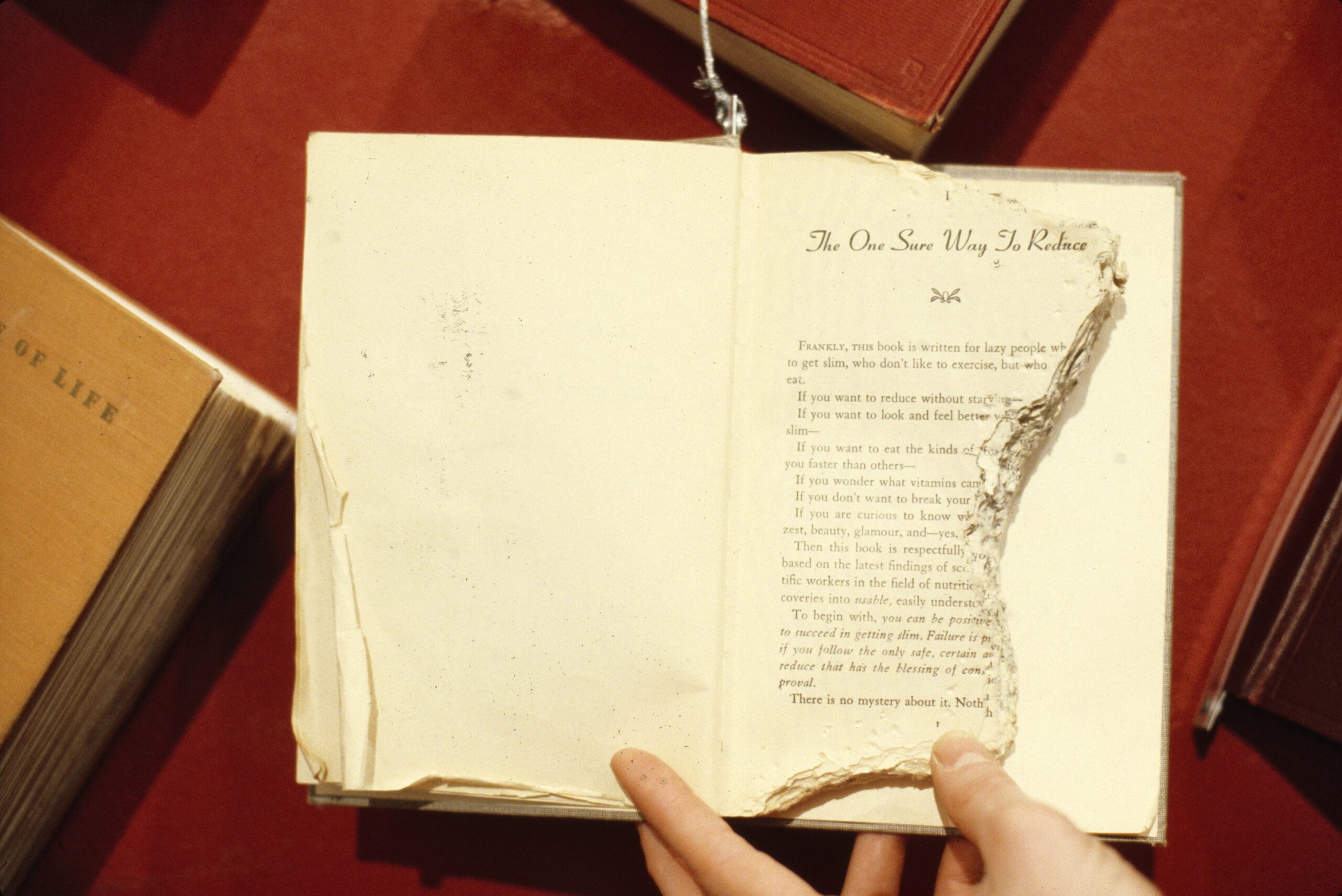

MT: It’s called “Not Just for Laughs: The Art of Subversion.”

JF: I have the feeling it will be as controversial as “Bad Painting.”

MT: Perhaps, although I didn’t intend for it to be. I began to see a lot of work that didn’t lend itself easily to any of the methods or modes of analyzing art. Then I began to read a great deal about how humor is structured.

These artists are so much outside the system that it was incredible to work with them. Almost none of them know each other. Some of them have never shown. One of them has never been to New York. They taught me a great deal. One of them said, “The question of quality is irrelevant in my work.” Another said, “I never had a career.” And another said, “I don’t have to justify anything to anybody.”

I took those statements seriously. One tends to think that political activists never have a sense of humour, but two of the artists in this exhibition are long-time political activists. Doing this exhibition threw open another way of thinking for me.

JF: In this exhibition, you’re dealing with another way to make for social change—through the role of the joker, the prankster who subverts (or perverts) through humor the system of society.

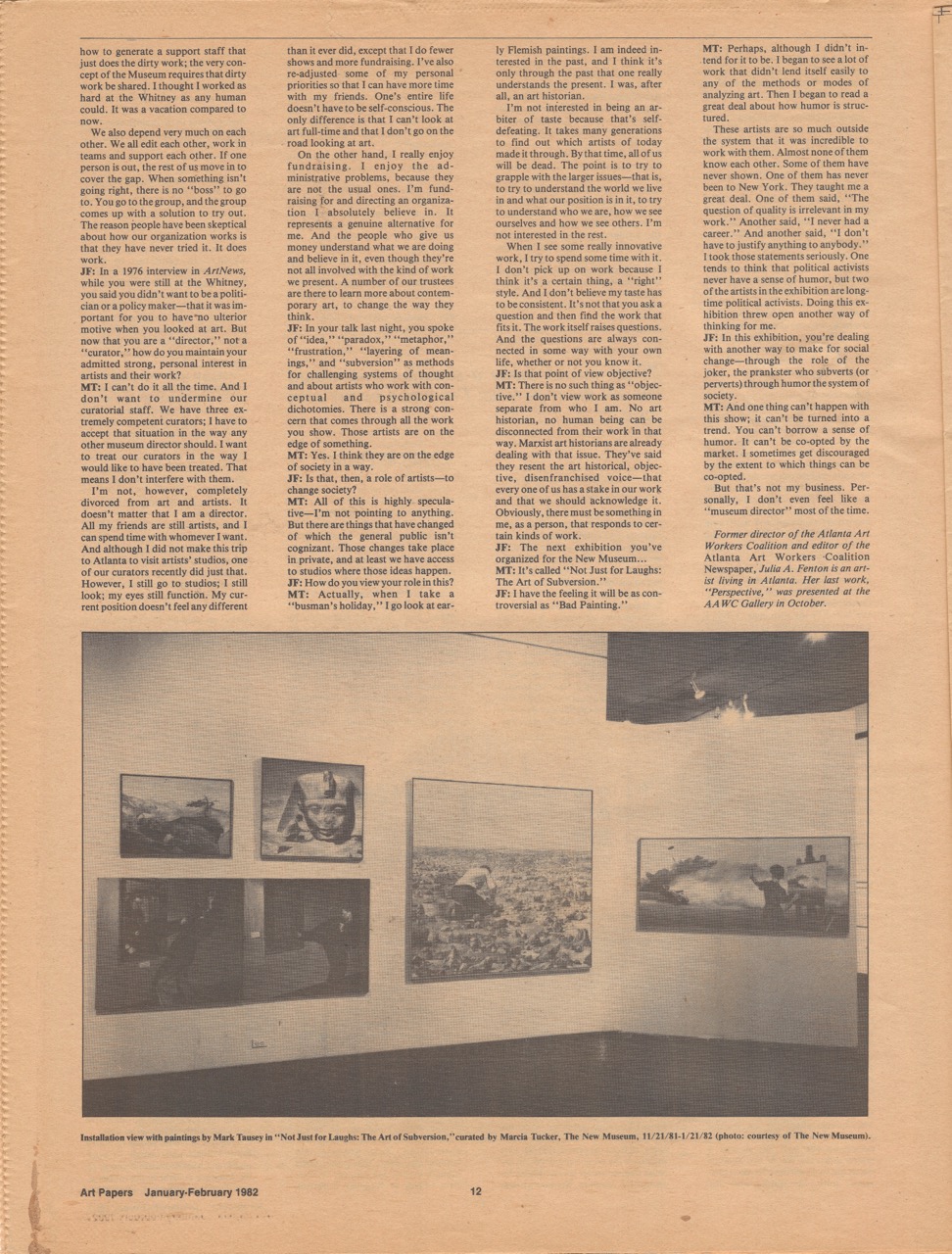

Not Just For Laughs: The Art of Subversion, 1981, installation view [courtesy of New Museum, New York]

Not Just For Laughs: The Art of Subversion, 1981, installation view [courtesy of New Museum, New York]

MT: And one thing can’t happen with this show; it can’t be turned into a trend. You can’t borrow a sense of humor. It can’t be co-opted by the market. I sometimes get discouraged by the extent to which things can be co-opted.

But that’s not my business. Personally, I don’t even feel like a “museum director” most of the time.

Former director of the Atlanta Art Workers Coalition and editor of the Atlanta Art Workers Coalition Newspaper, Julia A. Fenton is an artist living in Atlanta. Her last work, “Perspective,” was presented at the AAWC Gallery in October.