Lydia Ourahmane: صرخة شمسية Solar Cry

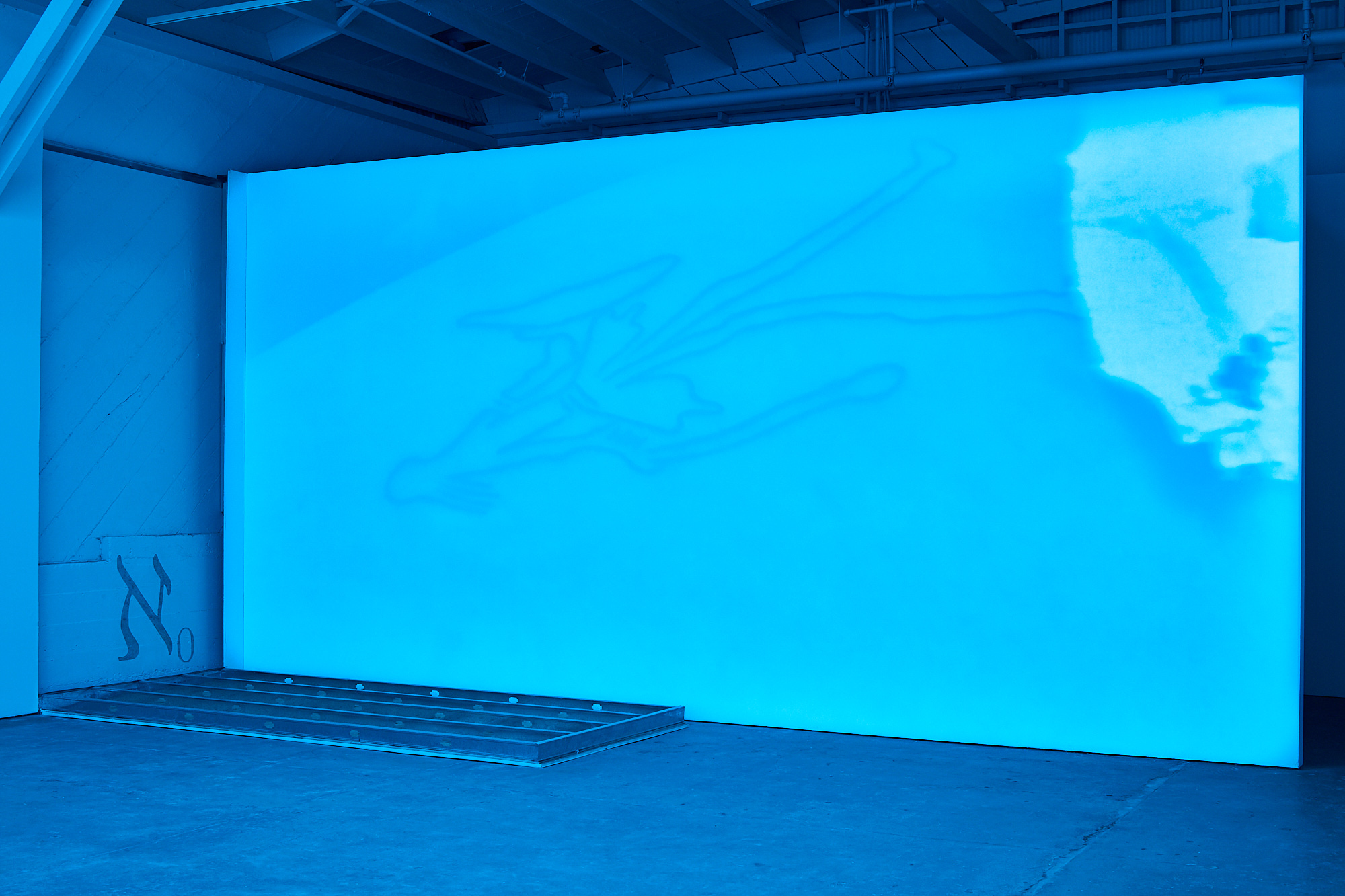

Lydia Ourahmane, صرخة شمسيةSolar Cry, 2020, installation view [photo: Impart Photography; courtesy of the artist and CCA Wattis Institute, San Francisco]

Share:

A visitor to Lydia Ourahmane’s صرخة شمسية Solar Cry steps from the street into a thick, disjointed song, an ambient howl—and immediately begins to interrupt its melody. Three kilos of salt, which coat the gallery floor, chime and croak with each footstep.

“I want to create a context that produces the potential for a miracle,” Ourahmane says.

The skylights and windows of the capacious CCA Wattis Institute of Contemporary Arts have been blocked with blue filters for the exhibition. It’s stunning. Less in the beautiful sense of the word than in the sense that it stops people and forces them to sensorially adjust. Blue light penetrates the human eye more effectively than any other color. It’s a vulnerable, nascent way of seeing—akin to the eyes widening.

In the exhibition’s most immediate work, Aa, Bb (2020), two recordings of an opera singer holding a single note play simultaneously. An A bellows from one side of the exhibition, while a B sings from the other. Singer Nikola Printz was asked to hold each note for an hour, with no referent point. This performance should be understood as an act of endurance, comparable to being punched in the arm over and over: a slow bruising of the vocal cords. Through exhaustion, through the emotional slippage that inflects the singer’s voice, the two notes occasionally slip below or above range and reach a perfect harmony.

In 2018 Semiotexte published a book of transcripts that document the artist David Wojnarowicz’s audio journals. Even though his narrative content is all bodies, fluids, and physicality, or perhaps because of that, I was disappointed to see that the book does not transcribe Wojnarowicz’s inadvertent noises—his moans and inhalations, the scratching of the nose or groin. Anything not encompassed by the English language’s strict conscription of sound was cut. Ourahmane’s Aa, Bb listens to the silence between vocalizations. It allows the singer to get tired, to sigh and exhale. Her breath acts as a reminder of the body being suppressed so that the voice can become an artistic material.

Lydia Ourahmane, Gold Digger, 2020-ongoing, metal detector, 1 gm of gold, sound, 23 5/8 x 33 5/8 inches [photo: Impart Photography; courtesy of the artist and CCA Wattis Institute, San Francisco]

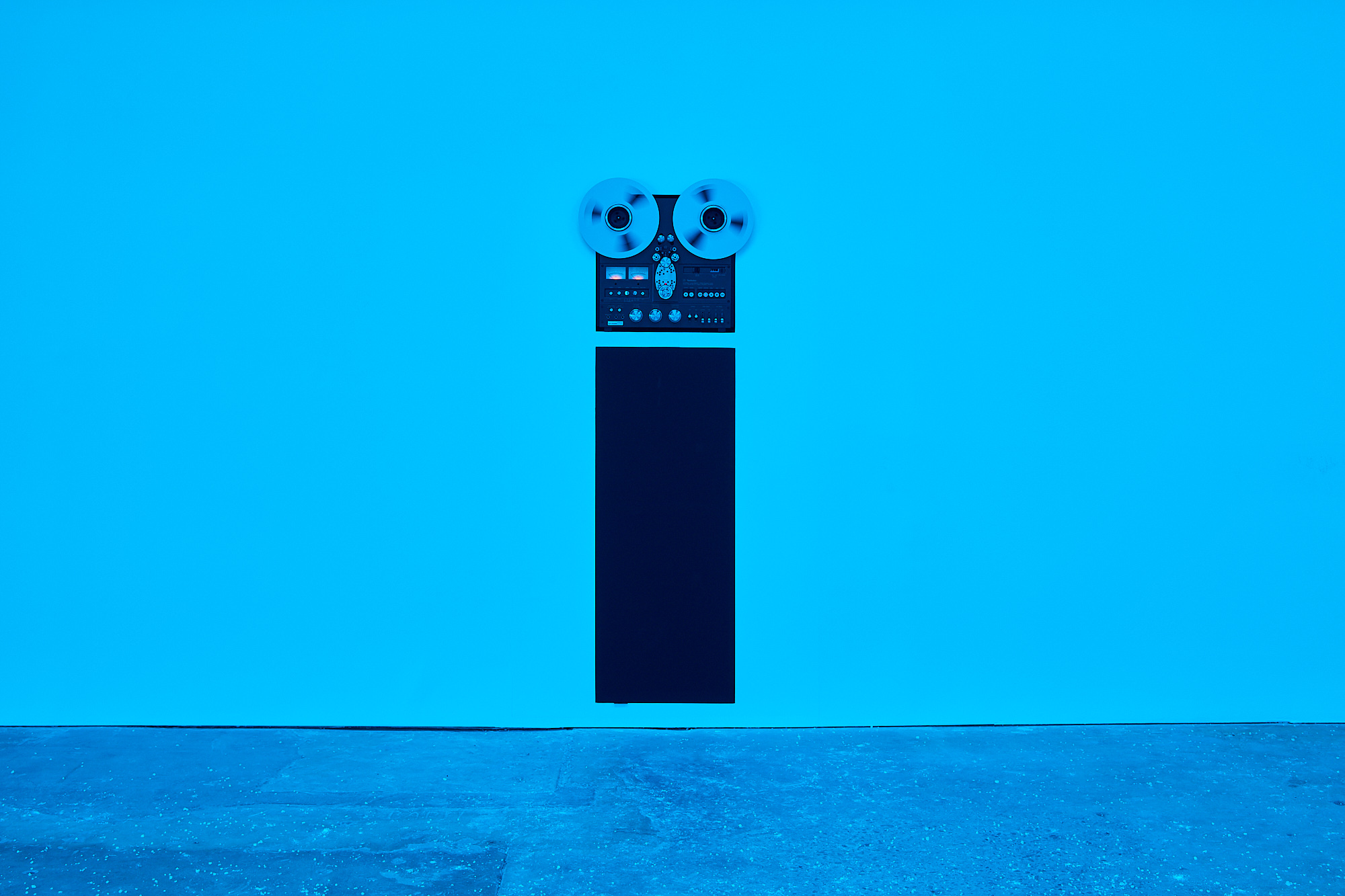

Across the room, permanently burrowed into the gallery’s cement floor, a piece of gold activates the tender receivers of a metal detector. The gold was given to Ourahmane when she visited Tassili n’Ajjer, a plateau of rock valleys in the Algerian Sahara. One of her guides there had a husky, empty voice. This—he explained to the artist—was because he had wandered the desert for five nights and five days without water.

In his former life as a gold miner, he struck a vein after extensive digging. Momentarily rich, he lost his fortune when he saw military tanks approaching in the distance. He dropped everything—his bags, his metal detector—and ran off with as much gold as he could carry. The exhibition’s metal detector is promised to him. Its pulsating melody takes on the weight of a livelihood.

The objects in Ourahmane’s first solo museum exhibition in the United States are like appendages. Everything is permeable. Everything avoids discretion. “I’m trying to get the guts out,” Ourahmane told me over a cigarette. “That’s my approach. I want people to encounter whatever I am trying to show in the closest way possible.” Some of her works reach for a landscape, others listen for a mother—there are apparitions of another body, of many other bodies.

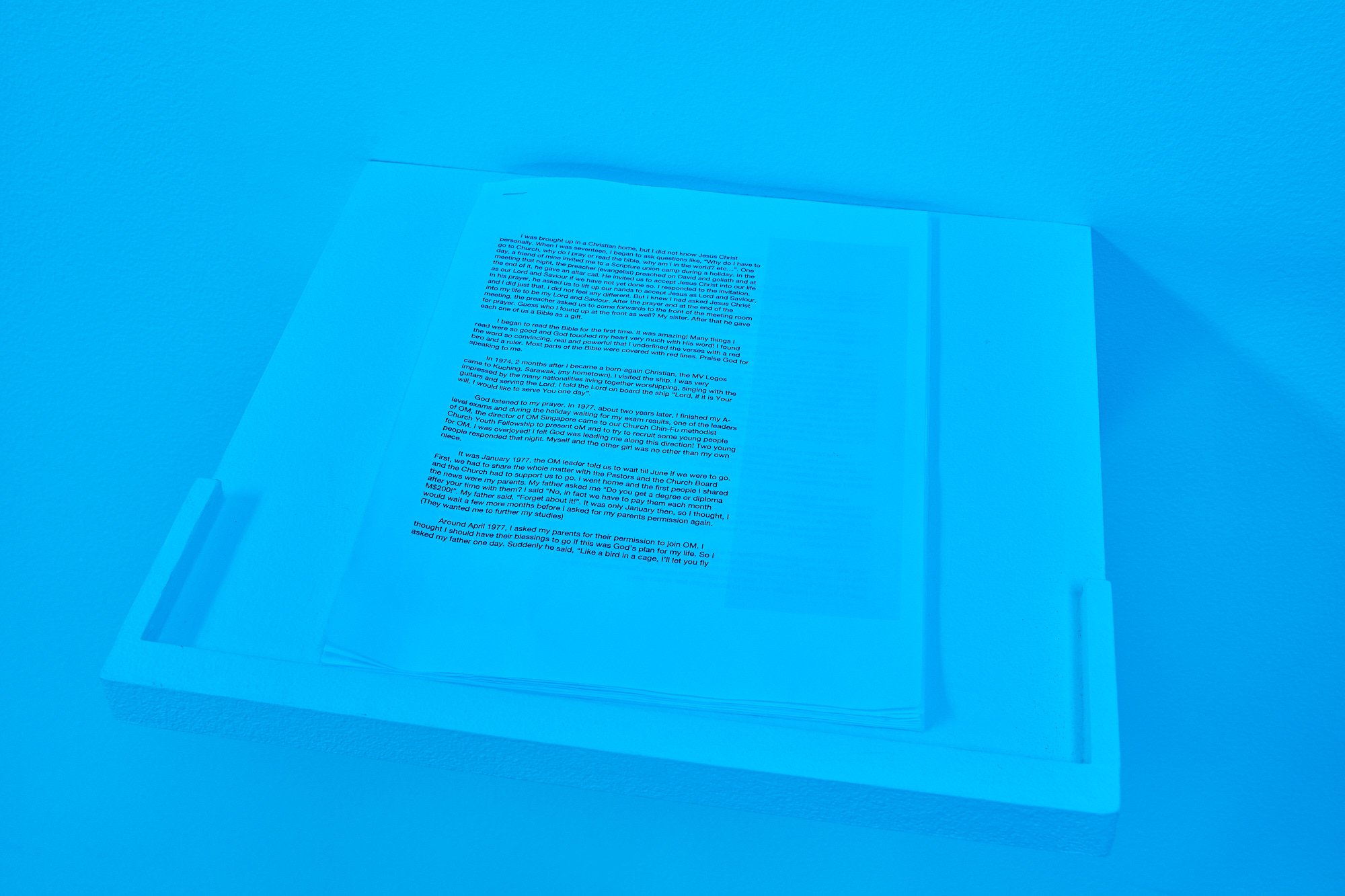

Ourahmane grew up in a Christian commune near Oran, Algeria, during the civil war. As told in her mother’s memoir, Divine Encounters—included in the exhibition as a printed stack of paper—the artist’s family returned to Algeria in 1996 to start a church, despite the dangerous conditions. They welcomed recent converts as Christianity became a kind of counterculture in reaction to fundamentalist applications of Islam. If faith is a bodily function, Divine Encounters stands in as its physical manifestation. Its inclusion is a way around reductive gestures toward religion, like the show’s blue light and sonic tones, which do not engage the contortions of language.

“I never spoke about this,” Ourahmane says, reflecting on her childhood. “Christianity, Islam, Counterculture—all these buzzwords are so heavy, so difficult to extrapolate from the systems of understanding we’ve already developed.” In working through language’s insufficiency, Ourahmane translated her experiences into image, sound, engraving. She traced their outlines to distill something unsayable. In that way, her works are onomatopoeic. Their semiotic content cannot be translated into English, or Arabic; though the show is bilingual, the works direct attention to their own materials.

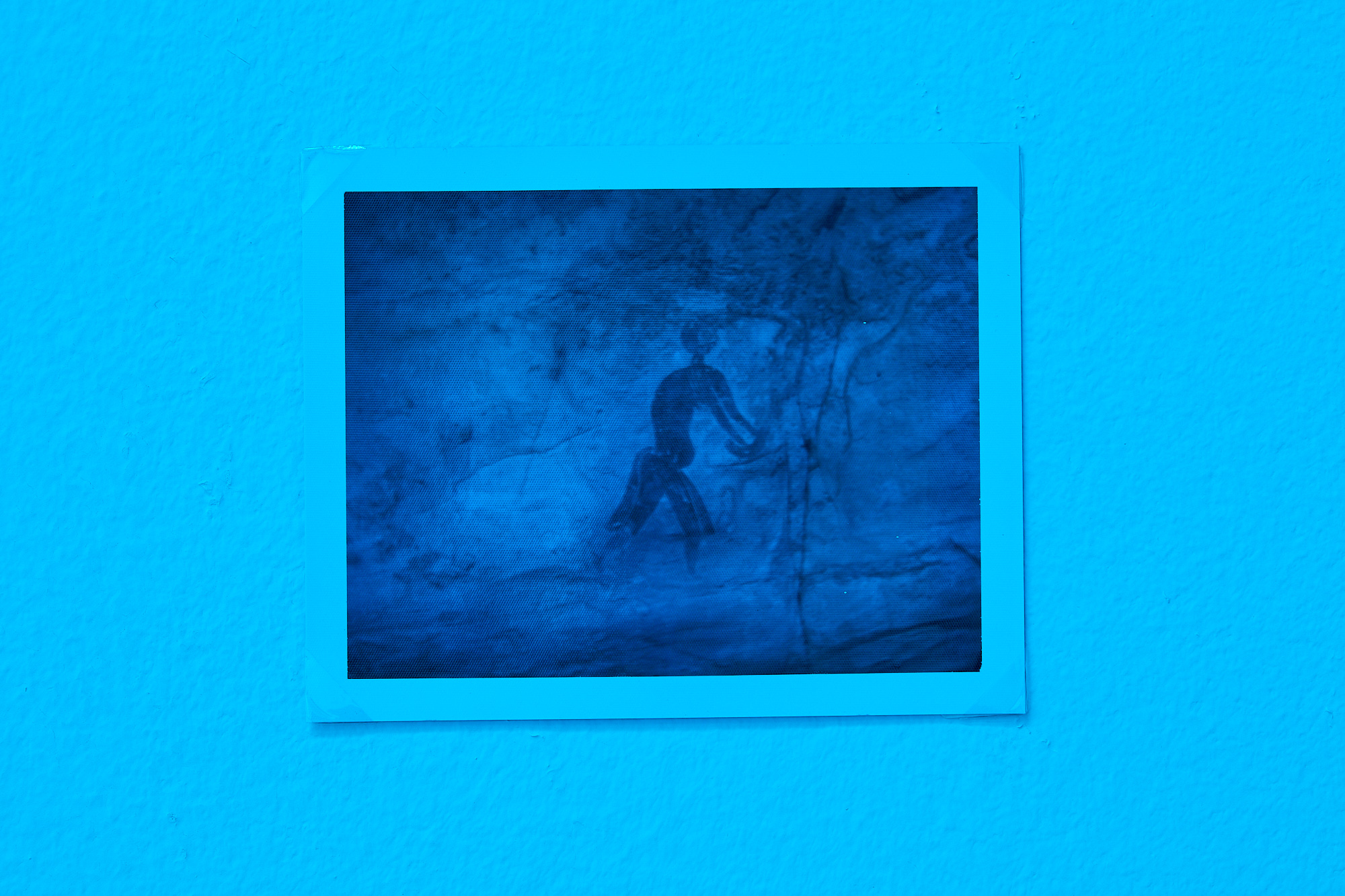

Lydia Ourahmane, Cave painting of a Woman giving birth c.6,000-12,000 b.c., 2020, polaroid; 3.75 x 4.25 inches [photo: Impart Photography; courtesy of the artist and CCA Wattis Institute, San Francisco]

This exhibition interestingly engages an identity not readily commodified by the art world: religion, which the artist has learned is a total fucking no-go in the art world. Short of constructing a church within the confines of a museum, صرخة شمسية Solar Cry makes space for something sacred.

A Polaroid in the show, Cave painting of a Woman giving birth c. 6000–12,000 b.c. (2020), is a tiny relic from Tassili n’Ajjer. It shows a dark figure standing next to a light one, a filled–in child next to a hollow mother. In the exhibition’s blue light, it’s difficult to discern the images’ outlines. From Emmanuel Levinas: prayer is a being disengaging itself from an unconditional attachment to being.

Ourahmane seriously considered naming the exhibition She gave birth on me. Why? “My sister did.” The artist explained, “We were in the car, and she let herself fall into my lap, and as she was falling, she pulled the baby out with one hand.”

In The Gender of Sound, a text chosen by Ourahmane to accompany Solar Cry, poet Anne Carson describes the Greek word ololyga: a ritual scream believed endemic to the condition of femininity. It is a high-pitched, guttural cry uttered at climactic moments of extreme pleasure or intense pain. It is a phonetic sounding of the throat’s most primal knowledge.

“The baby didn’t cry,” Ourahmane continued. “My sister stopped screaming. We were just waiting. That silence was one of the thickest moments of my life.” Then the baby made a first and most universal sound: it screamed. The short Bataille text in which Solar Cry eventually found its name suggests that the sun is the most abstract object. Although I see the glamor in that, I’d like to suggest the trachea.

Buried within a gallery wall, a recording of the quietest place Ourahmane could find in Tassili n’Ajjer vibrates like a vocal cord. “I want it to feel like a thickness,” she explained, “not a wall but a threshold.” The sound registers something essential, a shared frequency perceptible across the earth in various vast and incomprehensible landscapes. This work, titled Solar Cry, is heard by feeling, like a hand that gently rests on someone’s throat and understands meaning not by language but by way of a trembling in the neck. Is that not a form of prayer?

***

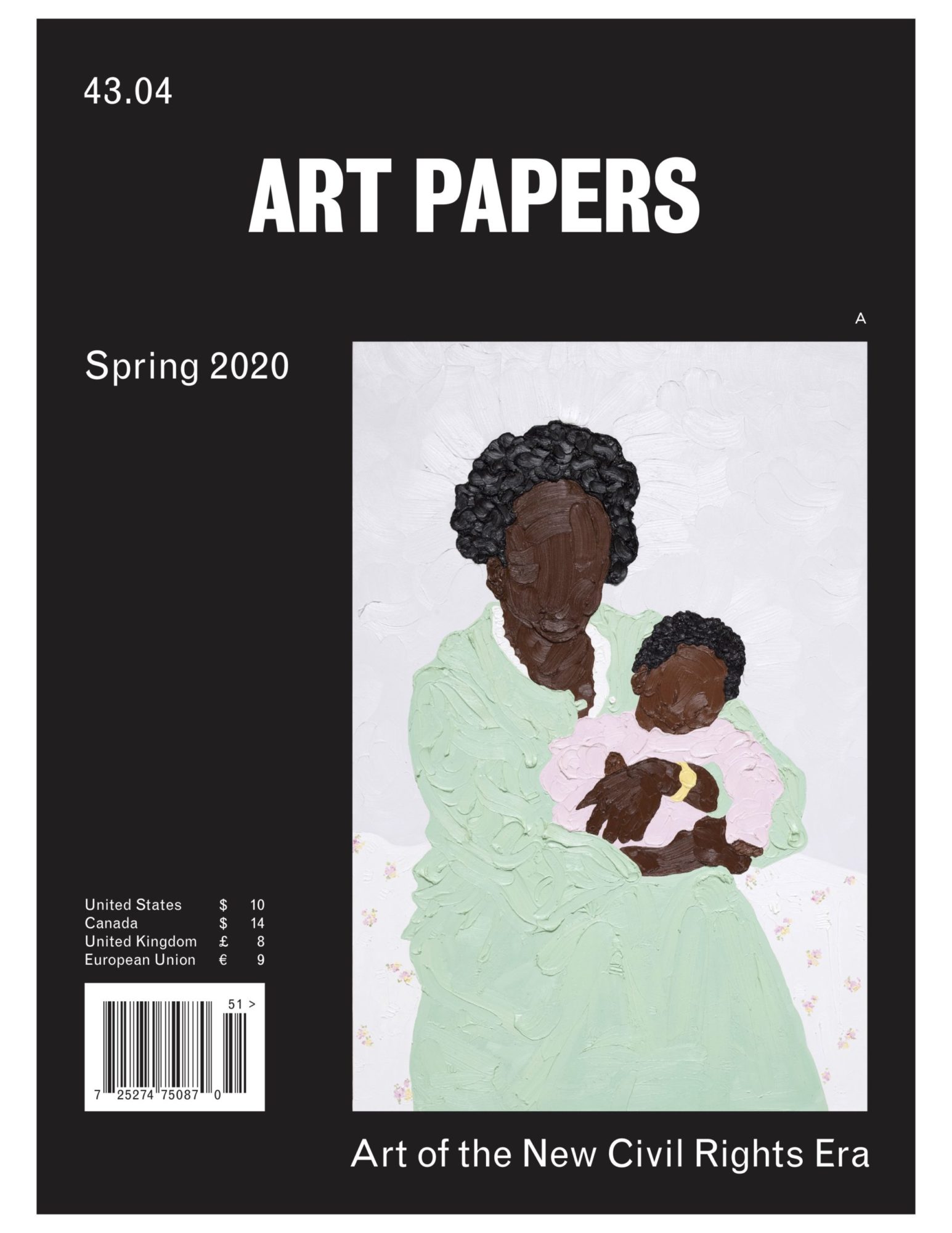

This review originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Spring 2020 // Art of the New Civil Rights Era.

Theadora Walsh is a writer and video artist from San Francisco. Her writing has appeared in ArtForum, SFMOMA Open Space, Gulf Coast Magazine, Unbag, BOMB, and elsewhere, and her videos have been shown by The Glucksman, the Granoff Center, The Shed, and Pratt University.