Look, it’s daybreak, dear, time to sing

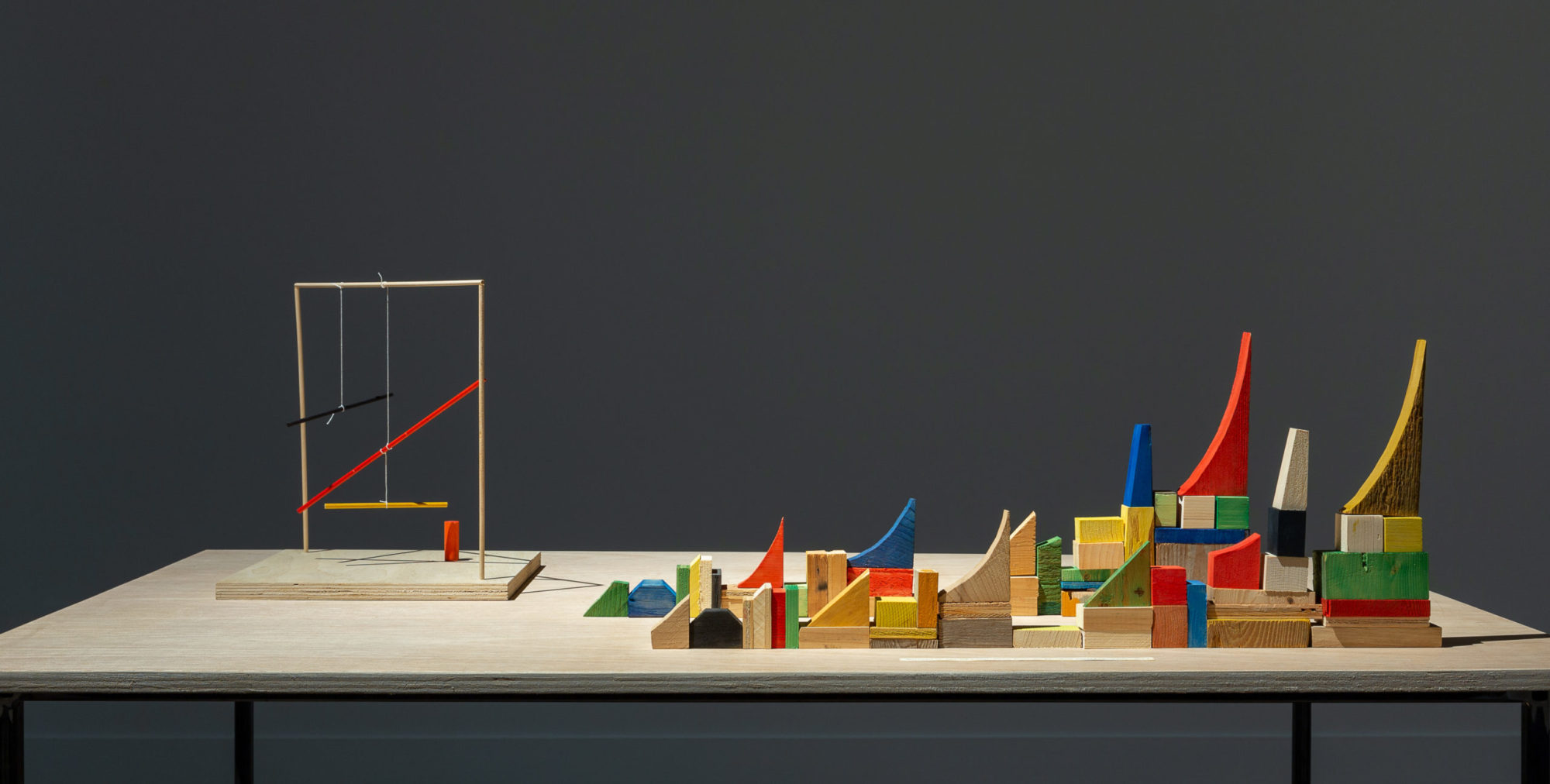

Richard Ibghy & Marilou Lemmens, “Look, it’s daybreak, dear, time to sing,” 2021, installation view [photo: H&S; courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita, Kansas]

Share:

Upward of 30 or more bird families are known to use simple tools. We humans ought not be surprised by the sapience of nonhuman creatures, yet such a view is fairly ingrained. It is also decidedly at cross-purposes with the discourse of anthropolitics in regard to anthropogenic mass extinction. Instances of human awakening and awareness, however, suggest possible, hopeful remediations. Such is the case with the modest, playful homage to avian ingenuity by Quebec artist duo Marilou Lemmens and Richard Ibghy, Community Toolshed for Birds (2021), which responds to lethal speciesism while poking fun at humans’ (dubious) surprise at the intelligence and interspecies amity of nonhuman beings.

The work is a major highlight of the duo’s exhibition, Look, it’s daybreak, dear, time to sing, at the Ulrich Museum of Art in Wichita, KS [August 19–December 4, 2021]. The project emerged from an artist residency at Omaha’s Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts and is part of an ongoing, fertile, collaborative effort with curator, researcher, and writer Sylvie Fortin.

The shed, constructed from weathered hemlock, is presented open to invite viewer scrutiny. Various tools are arranged neatly on three walls by category and are labeled—often quite humorously. A lending library of sorts, with an emphasis on community, the work mocks human incredulity where animal cognitive abilities are concerned and pays tribute to the rich sentience and ingenuity of other creatures. Despite persistent, essentialist notions of human primacy, we’ve learned that the use of tools and the development of language are not unique to humans. Birds communicate in sophisticated ways, and they fabricate and use basic tools. Community Toolshed challenges, explains Ibghy, “narratives of human exceptionalism.” Of course, he admits, there is irony in the fact that the shed and its contents were constructed by humans, for birds.

Community Toolshed is one of two new additions to the exhibition, which evolves as it migrates from one venue to the next. Through their videos and wooden sculptures, Lemmens and Ibghy pose questions far more frequently than they answer them. Indeed, the works in sum constitute a canny, urgent call to action and emphasize that there is enormous power to be found, even in the querying.

Richard Ibghy & Marilou Lemmens, “Community Toolshed for the Birds,” 2021 [photo: H&S; courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita, Kansas]

A foray into Lemmens and Ibghy’s joint ruminations on the ethics of care, and of humans’ increasingly lamentable stewardship of the environment, begins with a new work, Planting, Unplanting (2020). As in Feeding Cottonball (2019), an earlier video of theirs in which an aged hen is hand-fed by her human caregiver, humans are represented synecdochally: hands are agents of care and, conversely, control and culling. In Planting, Unplanting, a pair of hands thrusts aggressively into the soil; a hole is dug, a seedling planted, and the soil is pressed protectively around it. The process is repeated, row after row. The work of cultivation is a tedious affair. Then, unexpectedly, the hands return to uproot and destroy the plants, emphasizing the cyclical violence required to sustain human life—always at the cost of nonhuman life.

Look, it’s daybreak developed organically in response to the artists’ alarm at the sharp decline in bird populations that came and went at their farm in rural Quebec. The artists began investigating the matter and expanded their exploration to consider issues of interspecies relations, migration, territorialism, cohabitation, hospitality and care, and the impact of agriculture on birds.

Richard Ibghy & Marilou Lemmens, production still from “Planting, Unplanting,” 2019, single channel video with sound, 17 minutes [photo: H&S; courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita, Kansas]

Richard Ibghy & Marilou Lemmens, “Look, it’s daybreak, dear, time to sing,” 2021, installation view [photo: H&S; courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita, Kansas]

The Ulrich Museum’s iteration of the project presents videos and sculptures inspired by the artists’ engagement with zookeepers, conservationists, prairie preservationists, ornithologists, bird rehabilitators, and others. Another video, Cleaning the Atlantic Puffins, Tufted Puffins, and Common Murres’ Exhibit, confronts the ethical conundra of stewardship: A zookeeper methodically cleans the bird enclosures with a focus that verges upon reverence as puffins et al. cavort, seemingly unperturbed by his presence. His role as benevolent captor alludes to the complex web of human and nonhuman relations that connects the works in this exhibition.

The omnipresent threat of mass extinction—of birds, of entire ecosystems—and the seeming dearth of opportunities in which to put things aright, infuses the otherwise benign sculptures in the exhibition with an air of strange unease. In isolation, the small, (mostly) wooden artworks resemble colorful, minimalist maquettes or children’s blocks. Because optimum viewing of the videos requires low lighting in the galleries, the sculptures are displayed under bright, immersive light, which enhances the drama.

The titles of the wood sculptures, handwritten on small strips of paper, are unexpected: Sales Volume of the 10 Top Meat Processing Companies, The Same 627-ha Area of Agricultural Land in Clay County, Pounds of Glyphosate Applied in Top Soybean States (1996, 2006), and so on. They seem nonsensical; they destabilize. Drawn from a variety of sources, the data collected and reconceived in graphical 3-D arrangements relate to land use, including food and biofuel production, and the ecological and economic implications thereof. It is specific to North America and, as a result of the Bemis residency, to Nebraska.

Richard Ibghy & Marilou Lemmens, “Futures,” 2019, installation view [photo: H&S; courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita, Kansas]

Unlike such data artists as Laurie Frick and Nathalie Miebach—whose work lends materiality to data and, in the process, tends to emphasize the complexity of the information—Lemmens and Ibghy render the abstruse simple and palpable in their wood sculpture. The impulse to grasp, to rearrange, to play, has surprising, transformative power. For viewers, suddenly, the jig is up. We suspect that crucial information—dire warnings, even—have been deliberately obscured in benign, colorful graphs and charts. Meanwhile, we’ve nearly run out of time.

As we peruse the wood pieces, our soundtrack is birdsong and chatter. Connections are made with subtlety. The concerns of Lemmens and Ibghy—who maintain that they are not activists—alight and settle, then take flight again.

Look, it’s daybreak, dear, time to sing will continue to transform during its tenancy at the Ulrich, and as a result of Lemmens and Ibghy’s residency near the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in Matfield Green, KS (August 22–31). Afterward, it travels to Canada, to the Confederation Centre in Charlottetown (Prince Edward Island), where it will incorporate the artists’ Kansas prairie experience.

Editor’s Note: Sylvie Fortin served as executive director/editor of ART PAPERS from 2004 to 2012.

Debra Thimmesch is an art historian, activist, independent researcher and scholar, writer, editor, and visual artist. She mentors graduate students in the history of art and is attuned to current endeavors to radically rethink the reframing and pedagogy of art history. Her work has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail and Blind Field. Her BA in art history is from Wichita State University; master’s and doctoral work in art history: the University of Kansas.