Lilly McElroy: Absurdity Is a Protest

Lilly McElroy, Trying to Make Myself Reflective, #2, 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York]

Share:

This conversation is one of several that I undertook with artists from late April through early May 2020. People were still adjusting to self-quarantine, social distancing, working from home, and/or losing their jobs. In early May the world was already changing incomprehensibly from one week to the next. The passage of three weeks brought images of another Black man, George Floyd, killed at the hands of police, which catapulted the US into widespread civil unrest and public protest. This interview documents one moment of art making in a radically changing world.

I’ve been thinking about Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photos of empty theaters, drive-ins, and opera houses since social distancing and self-quarantining began. They depict vast spaces for the presentation of art that are devoid of people. That body of work was famously prompted by Sugimoto asking what it would be like to capture the entirety of a movie in one frame. The answer to that question, of course, is a glowing white screen that is the result of using one exposure to capture a whole film.

At the time of this writing I have not been in the Spencer Museum of Art, where I work, in eight weeks. The emptiness of vacated spaces really underscores what I am missing in a time when politics are failing us, and museum and exhibition spaces are closed. As a curator, one of my most important jobs is to get artists’ voices into public discourse. It’s funny now to think about Sugimoto’s series while introducing this interview with Lilly McElroy, wherein she describes hiding in the light, claiming that light sometimes exposes “a bright abyss.”

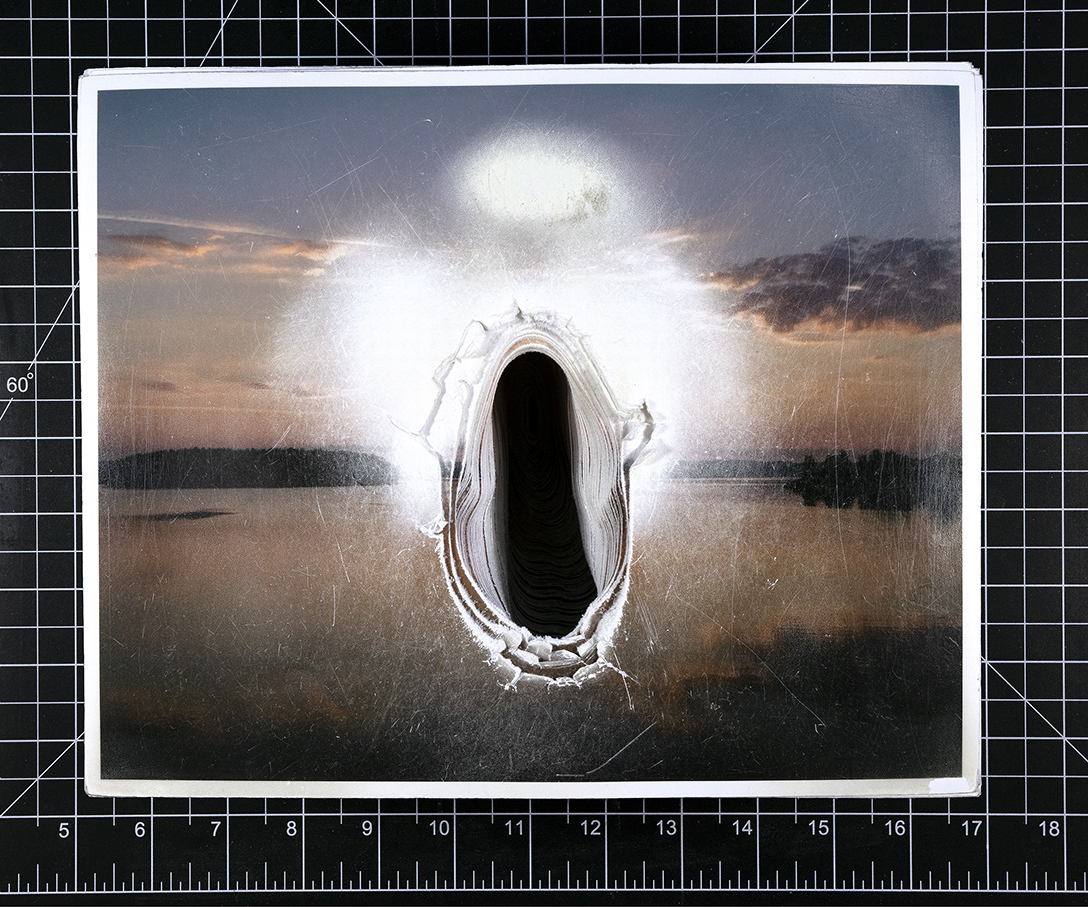

In her series I Control the Sun, the image of the sun on the horizon is always held in the circle of her hand. It is poetic to imagine a personal control that she can never achieve. In one of her most recent series, Sanding Away a Year’s Worth of Sunsets, she begins to physically wear away the light she’s captured from the sun in a year’s worth of photographs. Her defiant will in futile battle with the sun seems almost belligerent amid this deft performance. She’ll never win, of course, and she counts on her viewers understanding that fact in order to get at what’s human about making art. Her ability to manipulate the perception of light in her work reveals her inability, finally, to control it. She exposes herself as a photo-based artist by trying to control, extinguish, or as a last resort play tricks on the light—the very thing that defines her medium. As she says herself, “Absurdity is a protest.” Her Pandemic Self Portraiture series continues to wrestle with light and absurdity in a world transformed by a global virus.

Lilly McElroy, I Control the Sun #11, 2015, Archival pigment print, 40 x 40 inches [courtesy of the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York]

Joey Orr: Let’s begin with a quick answer to a ridiculous question. What is photography?

Lilly McElroy: I don’t have a good definition for photography. It feels so broad, and for me that is part of its appeal. Maybe it is simply creating a record with light while using any method available.

JO: Your series Finding Ways to Make Myself Reflective reminds me of other work you have done—I Control the Sun, for example. I have been thinking of both [these series as constituting] an explicit reference to your work with a light-based medium. Do you think about photography itself as being one of the subjects of your work?

LM: Absolutely. I think a lot about the functions and failures of photography. I love moments when a medium works against itself and generates friction. Photography is so much about the capture of light, but then there are instances when too much light makes it impossible to see. I’m using light and shiny materials to make myself reflective and therefore invisible.

JO: That’s really interesting. You’re sort of hiding in the light. What, then, does the light expose?

LM: A void or a bright abyss. Or maybe the fact that a camera can’t always create a complete record.

JO: I continue to watch your earlier video piece A Woman Runs Through A Pastoral Setting over and over and over again, not only because it resonates with my understanding of landscape as a cultural bracketing of “nature,” but also because I fall out of my chair laughing every single time I watch it. Every single time. Can you tell us a little about your interest in nature and landscape?

LM: My father is a falconer, and a lot of my childhood memories involve driving to or walking through expansive landscapes. My interest in it seems unavoidable, even though I spent my late teens and 20s either wanting to live or actually living in an urban location. I make art in order to try to understand things, and nature is something that I’ll never fully grasp. It is infinitely larger than I am. My existence doesn’t matter to it, and a lot of my pieces function as a futile argument against nature’s indifference. I also like thinking about the mythology of the West and the relationship of the female body to the landscape.

Lilly McElroy, I Control the Sun #27, 2016, Archival pigment print, 40 x 40 inches [courtesy of the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York]

JO: Is your father really a falconer?

LM: It is how my parents met.

JO: I love your comment that you made art in order to understand things—a kind of thinking through making. Has this always been your approach to art making? How did you come to have such a perspective on making?

LM: I think it has. Making work, for me, is based in curiosity; a curiosity about the world and culture and how people function within it. My explorations are often clumsy and personal. There is an element of stumbling that is human and imperfect. However, this type of making isn’t specific to my practice. I think a lot of art begins with someone asking a question.

JO: The first work of yours I ever saw was The Square—After Roberto Lopardo. In it, you defend a square of public sidewalk you’ve claimed from an onslaught of unsuspecting passersby. In the video, you vacillate between being defensive and playfully goading others into interacting. I Throw Myself at Men, a photographic series I also saw pretty early on, documents your performance of full body throws at men. The capture of such an abrupt movement documents a brutal physicality but is also devilishly farcical. These works are assertive in some ways, but also vulnerable and ironically tender. More recently, I feel like when your work has a human subject in it, it’s only you. Where did all the people go?

Lilly McElroy, Sanding Away a Year’s Worth of Sunsets, 2019, Archival inkjet print, 10 x 12 inches [courtesy of the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York]

LM: My work is, in part, about forming connections, but the types of connections have changed over time. At a certain point, people were replaced by the landscape. Now I’m in my house with my husband, my dog, and my Internet connection. I’m still trying to connect, but instead of leaping at men in bars or playing music to the landscape, I’m posting photographs on Instagram.

JO: At the time of this interview, I have also been working from home and sheltering in place for two months. One thing that has changed for me is that I’m spending more time on Instagram looking at the work artists are making. I found your new work there, and you turned me on to some other artists I hadn’t been looking at. During a time of social distancing, this kind of image exchange has replaced the studio visit. I assume sharing work through social media as you are making it means people are seeing it much sooner. How does that impact your thinking? Who are you in conversation with because of this kind of exchange?

LM: For me, making work through social media invites a certain kind of looseness that leads to experimentation. The work I’m making is quick and sketch-like; the idea is the primary concern. The stakes are low, and I get the opportunity to play and respond to the current situation.

I agree that social media can function as a kind of studio visit and lead to other, larger conversations. I’d been commenting back and forth with Angela Willetts for so long that we finally decided to have a Zoom studio visit. Jenny Kendler, a wonderful artist and activist, saw one of my photos and sent me a link to a piece by Mary Mattingly that I truly love. Gina Osterloh and I were able to have a conversation about the materials in our work. While I am looking forward to the day when we can have in-person studio visits again, it has been lovely to engage with other artists this way. I like the chattiness of it all.

Lilly McElroy, Things from My Floor That Stuck To My Hand: Self Portrait Made by Wrapping My Hand in Tape and Sticking It under My Bed, 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York]

Lilly McElroy, Trying to Make Myself Comfortable #2 (under every blanket in my house), 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York]

JO: Some [works] of the Pandemic Self Portraiture series we are sharing here were shot on your couch at home. You mentioned you were thinking about your couch as a performance space. Tell us what you mean by that.

LM: So much of my work relates to the landscape. I go out in the natural world to perform for the camera, often using expansive locations as characters and settings. Because of the pandemic, the spaces that I have access to and am thinking about are much more contained. I am now working from home and spending much more time on my couch. It has stopped being simply a piece of furniture where I safely nap and watch TV. My couch has become the little world where so many of my invisible internal dramas take place. I doubt I’m the only person who is experiencing this.

I’m using my couch as a symbolic space where I perform gestures that point to the horror and absurdity of our current experience. What happens when you no longer feel comfort? How do you keep yourself and the people you love safe during all of this? How do you stay sane? It seems impossible. My only option was to crawl under the couch cushions and make a photograph.

Lilly McElroy, Trying to Make Myself Comfortable, #1, 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York]

JO: It has been difficult to ask artists to reflect on our moment so soon. Everything seems to change week to week, or sometimes day to day. I spoke with an artist recently who was asked to share how her making had changed since the pandemic, and she responded: I’m not making anything right now. We’ve all had to take breaks from our habitual ways of operating in the world. And yet, with museums and exhibition spaces closed, I miss artists’ voices in public discourse. I think one of the things that makes this work powerful is that when you crawl under the couch cushions, you take your making with you. Why? How has this moment of withdrawal become such an amazing moment of making for you?

LM: This isn’t always a good thing, but working functions as a kind of security blanket for me, and making photographs gives me something to do with all the fear, anger, and frustration that I’m feeling. I also tend to work, at least at the beginning of projects, improvisationally. I’m accustomed to trying things and often having them fail.

My role as an educator also has a lot to do with it. [Although] I don’t think artists should feel any pressure to produce during all of this, I want my students to get the best education possible while still having the space to maneuver through this uncertainty. I started making self-portraits while I was figuring out how to move my photography classes online. Instagram was something I knew they would all be able to access, so I essentially gave them the same assignment that I gave myself. I benefited because I was trying to stick to the same deadlines. That helped me both start and keep working.

Lilly McElroy, I Stuck My Face in the Prettiest Thing I Could Find, 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York]

I assigned this self-portraiture project to my sophomore-level classes at both University of Kansas and the Kansas City Art Institute (KCAI), and both groups have produced some truly lovely responses. Actually, a great thing happened with the assignment at KCAI. My colleague Trey Hock suggested expanding it by inviting other departments to participate. He helped turn it into a larger community project, and the collaboration with him has been wonderful.

JO: In one of your Instagram posts you reference the late photographer Francesca Woodman, and in another you tag contemporary artist Angela Willetts. How does your connection to past and present contemporary artists factor into this work?

LM: I remember where I was the first time I saw Francesca Woodman’s work, and I’m now realizing that I’ve been thinking about her photographs for almost 16 years. My own work is inevitably going to be in conversation with the artists who resonate for me. Most of the time, the relationship isn’t this overt, but in this instance it felt good to make something more direct. I know this sounds cheesy, but her work has been speaking to me for such a long time that it felt nice to say something back. Also, her relationship to surrealism feels relevant to our current situation.

The list of artists whose work I love and who influence my practice is very long. The conversation I’ve been having with Angela Willetts and her work [is] important and fluid. She is an artist who also uses the landscape as a performance space. Her videos are beautiful and strange and far more delicate than anything I could aspire to. During the pandemic, she has also begun to make work in her home, and it has been really helpful to see what she is producing. She recently made a video in which she is performing on her couch. The best way that I can describe it is, kaleidoscopic. She is embracing the surreal. The way Mitchell Squire is using the body is also having an effect on the way that I make photographs.

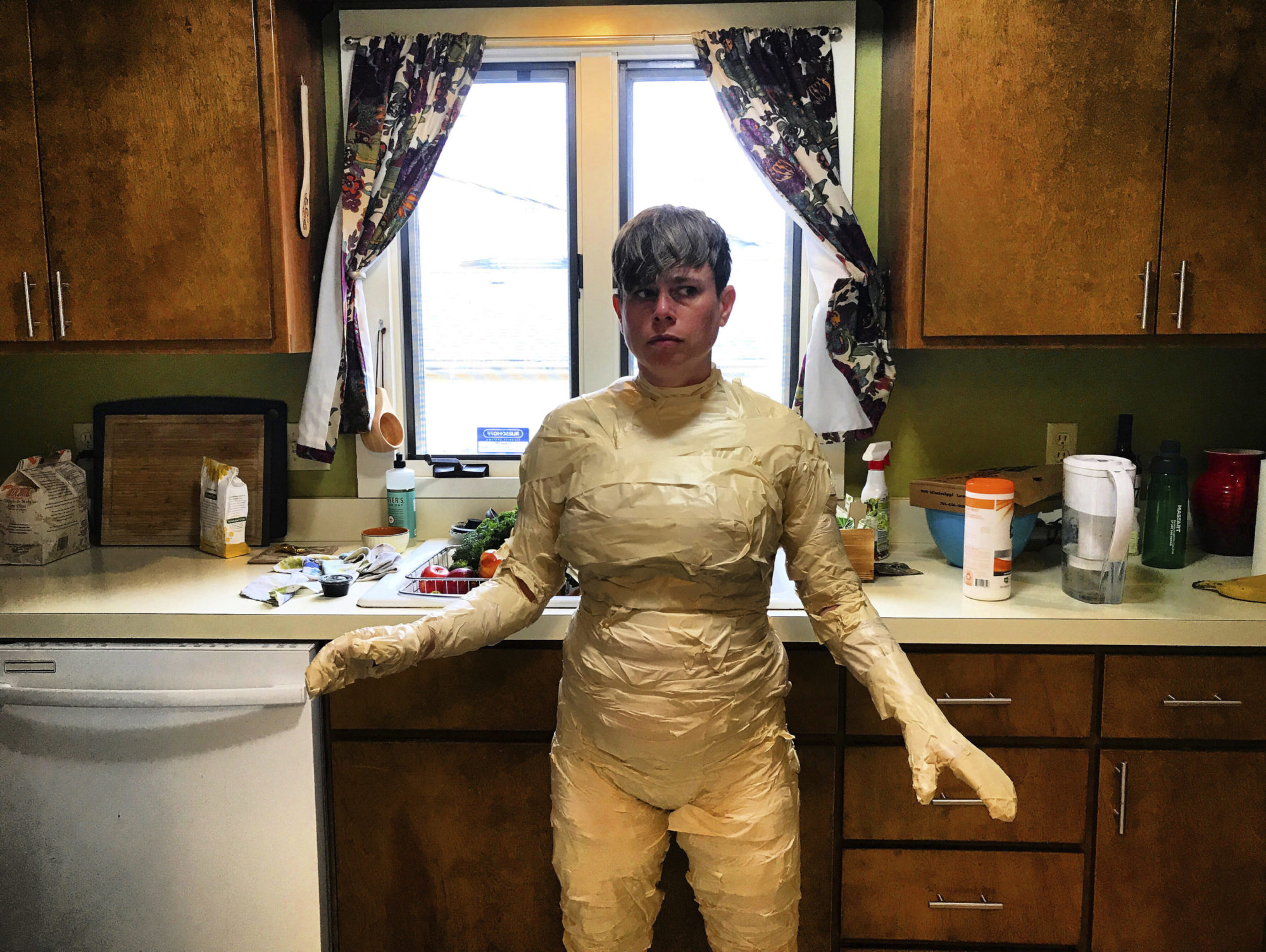

Lilly McElroy, In My Kitchen, Covered in Tape, and Waiting for Things to Stick to Me, 2020 [courtesy of the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art, New York]

JO: Your image In My Kitchen, Covered in Tape and Waiting for Things to Stick to Me is so illustrative of your tactics as an artist. For me, now, these images are about contagion and the weirdness of living in a quarantined world, but they also leverage your sense of humor. Sometimes your work functions by using abrupt and unexpected juxtapositions that disarm [viewers] and open them to the images in less guarded ways. How do you think about the absurd in your work?

LM: Humor is such a useful tool, and existence feels so absurd even when we are not in the middle of a pandemic. I use jokes and slapstick to disarm [viewers], and to hopefully make them think about complicated and difficult ideas. That photograph in my kitchen is about the horror that comes when you have to acknowledge that it is impossible to keep yourself truly safe. It is dark as well as ridiculous, and there is nothing to do except laugh. Absurdity is a protest or push back against things that seem insurmountable.

Actually, I just googled “Absurdity of Existence,” and I really like the definition and image that came up. To paraphrase the Internet, it is the conflict between our need for life to have meaning and the universal truth that it doesn’t. That is bleak and so perfect. The image was The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dalí. Right now, time definitely feels as though it is drooping.

JO: The related images, What My Tape Outfit Turned Into After I Took It Off and Things From My Floor That Stuck to My Feet: Self Portrait Made by Wrapping My Feet in Tape and Walking Around Until They Were No Longer Sticky, document the ephemera of your performances at home. Do you also understand them as sculptural objects in their own right? Would you ever exhibit them?

LM: Those tape feet are on the floor next to my couch, and I’m not sure what to do with them. For now, I think they have to live as photographs. It allows them to be seen in the best light, and [to] be simultaneously beautiful and disgusting.

***

This interview originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Summer 2020 // Living & Working.