“Vegas Vicky,” Fremont Street Experience in Downtown Las Vegas, neon curated by Neon Museum, Las Vegas [photo: Antoine Taveneaux; via Wikimedia Commons]

Las Vegas: Still Learning?

Share:

How do you shape the future of a city for a new, globalizing century— when it was an anomaly in the last one?

In the long tradition of writings and films about Las Vegas, the city is known first from the road—famously, in works such as Terry Gilliam’s film adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), joined by bachelor buddy movies that begin with a road trip from Los Angeles. Today a motorist entering Las Vegas can no longer burn rubber along the Strip as she might have in the loathsome days of Hunter S. Thompson—nor can the architecture student marvel judiciously at the budding urban sprawl as she might have as part of Denise Scott Brown’s and Robert Venturi’s Yale research studio in the 1960s. Instead, drivers creep along in stop and start traffic—or perhaps they are passengers, in the backseat of an Uber—and as they roll slowly by, each sparkling new casino and aging neon façade becomes an intimate visual, framed and flattened by the car windows into a postcard or a slide in an old View-Master, through which the city is experienced as a series of relics of a bygone modern era.

Photographs of the Las Vegas Strip have a tendency to look like documents of science fiction film sets, not pictures of “real” places—an effect of persistent simulacrum, distilled in images of neon signs and billboards, and rendered in shades of the apocryphal. Vegas has always been a “future city”; like other future cities it seems to have emerged fully formed from sand or some hostile material, on a site chosen for— not despite—its expansive emptiness. When this future city appeared is unclear: it is perpetually “new,” it is digitized, and yet supporting its sophisticated screens is a grungy longevity suggestive of old bones.

Settled in 1905 and incorporated in 1911, Vegas is a city whose entire history is contained in the 20th and 21st centuries. It is perhaps unsurprisingly younger than its most essential constituents: air conditioning (b. 1902), synthetic plastic (b. 1907), and the neon lamp (b. 1910). Nestled alone and improbably at the state’s southernmost point—and in the Mojave Desert—Las Vegas performs vestiges of a Wild West it was never strictly a part of. Las Vegas is thus at once escapist, equalizing, and anachronistic: the place to realize an “American dream” that oddly precedes it, or simply to manifest density with a well-timed gamble. Yet there is a persistent tension in the city between its seemingly “ancient” roots out West and its assured identity as a unique international destination—an important feature in our increasingly globalized future. Like much of the United States today, Las Vegas seems to be seeking “placeness.” But what does it mean, to permanent residents and to tourists, to make a “place” as the ground below shifts and swells?

[courtesy of the Neon Museum and Vox Solid Communications]

To suggest Las Vegas as a site for taking the pulse of the nation is not particularly original. In fact, it is a tradition. Vegas’ relevance as a gauge is the founding assumption of critic Dave Hickey’s work on the city in the late 1990s, when he suggested that “America … is a very poor lens through which to view Las Vegas, while Las Vegas is a wonderful lens through which to view America.”1 Hickey’s study of Las Vegas is predated by the now canonical architectural study, Learning From Las Vegas. Half a century ago, in 1968, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown published “A Significance for A&P Parking Lots, or Learning From Las Vegas,” which led to a graduate research studio and the publication of the full-length book in 1972. Appropriately concerned with sign and symbol, Learning From Las Vegas asserted that the expansion of the commercial “strip” was key to understanding the then “new type of urban form emerging in America.”2 Venturi and Brown’s central premise was that Las Vegas was fertile ground for describing urban development as it related to future cities’ potential.

This ethos of Vegas-as-model persists even in what we have come to call “Trump’s America.” Organizers of the 2018 Women’s March chose Las Vegas as the epicenter of the second annual nationwide event. Because the city is the location of the nation’s deadliest mass shooting to date and home to a record number of local female politicians—as well as what looms as a contentious round of 2018 midterms— movement leaders saw the city as an apt locus for their national discourse. Like much of the country, Las Vegas is undergoing a profound shift in identity, both economic and cultural. Casinos, once the shimmering stalwarts of the Strip, have yet to recover from the Great Recession, and 2017 was a particularly bad year for gambling revenue. Total state wide gaming revenue fell from 62% to 42% last year, a historic low for the industry.3 Some of the most recent losses might be attributed to cancelled visits following the shooting deaths of 58 people at an outdoor concert, but nongaming revenue from accommodations and entertainment are up, and tourism in general is on the rise. What is occurring in Vegas, then, isn’t a loss per se but a shift in focus away from the city’s original offering—and away, perhaps, from its core self-image.

[courtesy of the Neon Museum and Vox Solid Communications]

The Las Vegas valley is home to a sizeable and diverse population of two million locals and counting; increasingly, not all of them work in “the industry.” Access to “Culture” is high on the millennial list of quality of life priorities. While Las Vegas has endless options in entertainment— Britney Spears concerts, themed rides, multiple simultaneous editions of Cirque du Soleil— the city is remarkably lacking in the types of visual arts institutions typical of a city of its size (particularly one so famous for its captivating visuals). The state’s museum of record is the ambitious and thriving Nevada Museum of Art, located in Reno. At the University of Nevada Las Vegas (UNLV), the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art is home to a collection of traditional visual cultural artifacts from pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, however, and UNLV and its supporters appear to be investing in cultural production. In 2017 its Beverly Rogers, Carol C. Harter Black Mountain Institute (BMI) acquired the critically acclaimed magazine The Believer from the California publishing nonprofit McSweeney’s and launched an annual The Believer Festival in collaboration with the publication’s co-founders, who now serve as consultants to the new BMI and UNLV editors. The BMI has also hosted a Las Vegas branch of the fascinating City of Asylum program, a residency for international writers under threat of censorship.

[courtesy of Zappos]

Outside academia, only a small gallery scene serves contemporary visual artists and their fellow creatives. The Contemporary Arts Center and Trifecta Gallery, two well-regarded spaces that produced thoughtful and content-heavy exhibitions of contemporary art, both closed in 2015 after struggling for some time.4 Yet there is evidence that the community is rallying to fill the void. Las Vegas Boulevard, is Downtown Las Vegas (DTLV), the focal point of arts-oriented development and home to the city’s aspiring “arts district.” With a dream to attract and serve both residents and those visitors interested in more than the expensive risks (and cheap thrills) of the Strip, DTLV is undergoing a transformation reminiscent of ones afoot in many postindustrial urban areas being rebranded as four-letter acronyms, their disused factories and heavy transport corridors changed into tech- and creative-industry-focused mixed-use facilities concentrating upon luxury condos and “walkable” commercial nooks of independent businesses and craft restaurants. True to form, of course, Vegas has approached such projects with its own flair. Leading the DTLV redevelopment is the online retail juggernaut, Zappos.

In 2013, when Zappos moved its headquarters from Henderson, 16 miles southeast of Las Vegas, into City Hall in DTLV, taking over an entire city block and launching the $350 million Downtown Project, its ambition was—and remains—to create an urban utopia there. This vision included a 60-acre district in which “live, work, explore” spaces—and Downtown Container Park, an outdoor mall made from shipping containers—would be built to house the flourishing Zappos community and its neighbors. Zappos’ Downtown also represented a private attempt to integrate otherwise disconnected or disused areas of the city, with a goal to weave affordable living options into a plan for high-rise luxury condos, and to commingle trendy “cheap eats” venues with exclusive restaurants. Like many other tech- and culture-driven development projects, this equitable dream was pursued in part through the commissioning of local artists for interior and exterior murals—billboards for corporate money in the service of local business and community development.

[courtesy of Zappos]

The critical reception of the project has, thus far, been mixed, and the jury’s out on its local impact. As a condition of Zappos’ acquisition by Amazon in 2009, longtime CEO Tony Hsieh runs the business wholly autonomously. The result is not only an urbanist impulse but a business model-cum-social experiment in which job titles and managerial hierarchies have been eliminated and apparently replaced by focus on lifestyle and community development. In fact, Hsieh’s heavy investment in culture—inside Zappos’s HQ, in the company culture and outside its walls, in the cultural identity and offerings of its DTLV neighborhood—appears to have supplanted any concern for maximizing profit. Of course, whether this gamble has paid off in Zappos’ leadership’s view (or in the view of its parent, Amazon) remains opaque.

The past two decades in DTLV have brought a growing number of large, adapted industrial spaces—including Emergency Arts, housed in a former medical facility; and The Arts Factory, in a former commercial warehouse—that are multipurpose, incorporating studio, gallery (including the Contemporary Arts Center until its closure), and small business communities. These compounds’ goals are often along the lines of Emergency Arts’ stated mission: to “[embrace the] city’s new identity as an international arts and entrepreneurial destination!”5 What is unclear, however, is whether such projects have successfully attracted that cultural status. (Vegas does not, for example, appear to have been able to keep galleries in its aspiring arts district.)

There has been no shortage of attempts to crystallize a thriving and international arts profile for Las Vegas, and the Great Recession hit such initiatives hard. The Las Vegas Art Museum was founded in 1974 and last directed by curator and art historian Libby Lumpkin. Under her leadership, the beleaguered institution showcased a succession of postmodern and contemporary shows, including a survey of California minimalists that featured James Turrell and Robert Irwin.6 Yet the museum closed in 2009, citing lack of funds. Before that closure, Las Vegas had attracted the Solomon R. Guggenheim foundation, which opened a Guggenheim annex in the city in 2001. Designed by and administered in collaboration with the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, the project was operated out of the Venetian Resort on the Strip, where it served a total of 1.1 million visitors before its closure in 2008. (More than 500,000 people per year ride the Venetian’s famed gondolas.7)

[courtesy of Zappos]

Las Vegas’ most “serious” contemporary artistic endeavors—and in a sense its most enduring—seem to last longer in the desert outside the city. There, sculptor Michael Heizer, living in self-imposed exile in Nevada, chose to locate his two most important works to date: Double Negative (1969) and the ongoing City (1972–), located roughly 80 miles east and 150 miles north of the city, respectively. A product of 60s minimalism who relocated to the stark deserts of the American west, Heizer is not an artist whose works are typically associated with the flashy, ornate, unruly visual landscape of Las Vegas. Yet his Nevada projects nonetheless mirror the nature of their largest metropolitan neighbor in size, in their unmitigated ambition, and in their post-apocalyptic aura of recent or future ruins. Carved and blasted into the edge of Mormon Mesa, Double Negative consists of two deep cuts oriented almost perfectly on a north/south axis, creating a deep strip in the earth. The cuts mirror each other across a shallow, wide canyon and are 1,500 feet long, thirty feet wide, and fifty feet deep.8 Each cut can be entered from either end by steep, earthen ramps. Writing on sculpture in 1977, art historian Rosalind Krauss located the phenomenological experience of viewing Double Negative from the center of the cut, where a viewer can fully imagine the work as a continuous whole.9 Because of its size, Double Negative resists total comprehension: viewers cannot observe its entirety from the ground. A visual understanding of the work is achievable from an aerial view, but that approach would deprive the viewer of the continuous experience described by Krauss, from within. Double Negative is felt wholly in situ, cut off from and yet somehow inside the landscape—an analogy for the Vegas Strip both morphologically and experientially. Impossible to comprehend in its totality, open to the world, and yet enclosed—either by the natural environment or the built one, by neon advertisements and iconic landmarks—both are staging areas for a virtual reality in which the payoff requires an intense physical immersion, inside a dark, linear strip.

Michael Heizer, Double Negative, 1969-1970, 240,000-ton displacement of rhyolite and sandstone, Mormon Mesa, Overton, Nevada [photo: Tom Vinetz; courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Gift of Virginia Dwan]

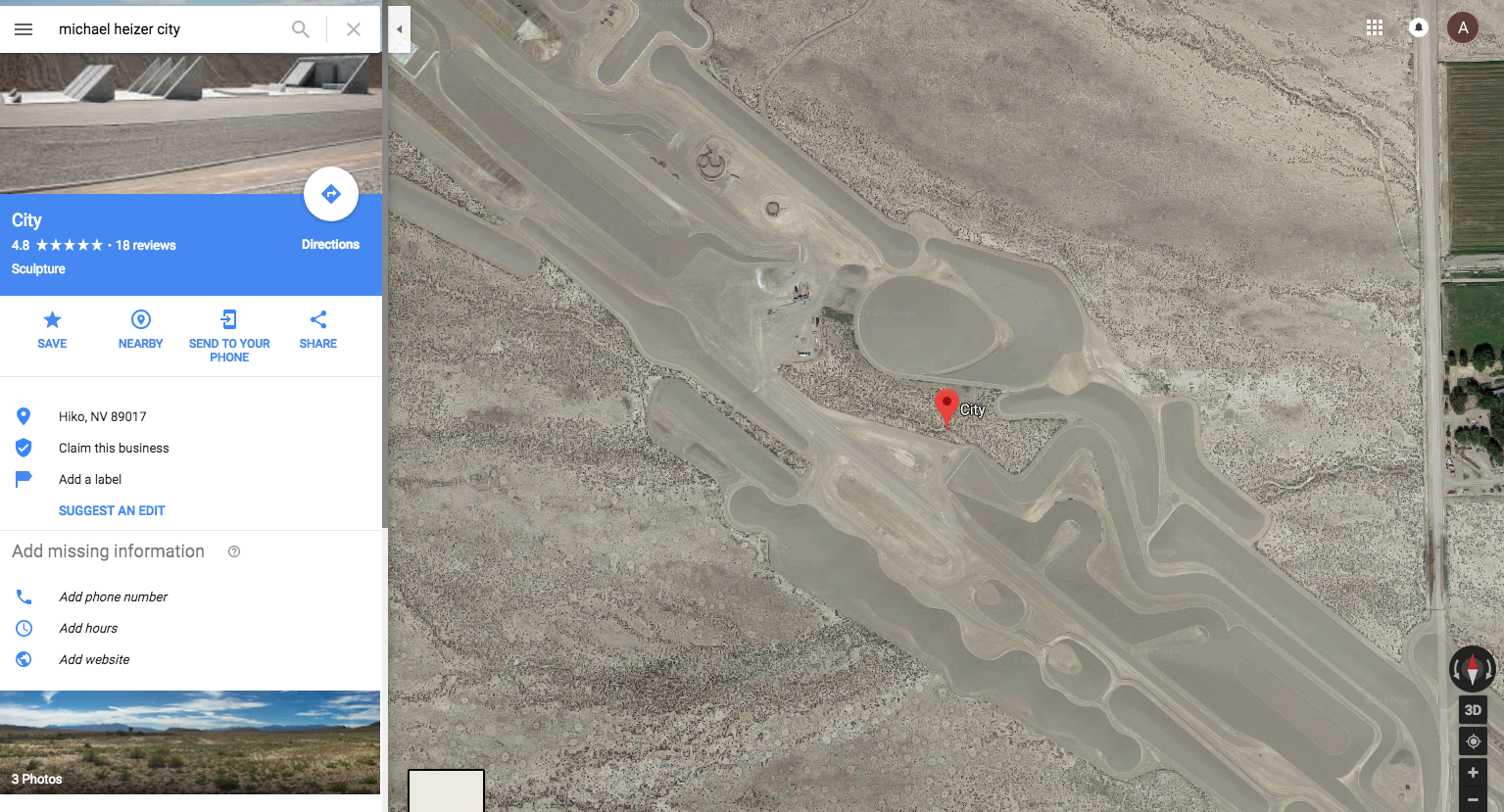

Four hours directly north of Las Vegas is Heizer’s still-unfinished magnum opus, City. Started in 1972, City is set to open to the public in 2020, at which point, if all goes according to plan (and nothing else comes along), it may be the largest sculpture ever built by a modern artist.10 A mile and half long and a quarter mile wide, City is a series of “complexes” made of reinforced concrete, packed earth, excavated on-site and spread across a strip of raked gravel. City’s remote desert location, like Double Negative’s, throws the work into dialogue with notable locations such as the Nevada Test Site and Area 51. Heizer began the project during the Vietnam War and a period of nuclear paranoia; appropriately, Complex I includes a wall capable of withstanding a nuclear blast—a minor fortress. This work is meant to outlast not only its maker but also humanity.

Despite recalling ziggurats and Mesoamerican pyramids, Heizer’s complexes seem, from a distance, less fixed than their size implies. The large concert arms that outline the edges of Complex I, for example, appear to morph and split as a viewer moves around the structure. With these shifting forms, City seems to melt, slipping between past, present, and future—a malleable aesthetic that intentionally situates the work outside of time. This timelessness is accentuated by the lack and seeming impossibility of its inhabitation: it could be a long-abandoned prehistoric site, or a settlement awaiting future residents, but it certainly doesn’t contain “real” life—an empty mirror image of the endless potential and perpetual erosion of Vegas myth. Far away from the city’s downtown and its attempts to sprout cultural enterprise, Heizer is building a truly Las Vegas contemporary art experience—esoteric, inaccessible, and fun, just like all the promises of the Strip.

Heizer’s City is a strip, too; like Las Vegas, it is conceived around a long, narrow plot of land. That is not to say that the strip is simply a “natural” form we return to, but rather that it is a productive structural tool, in Venturi and Scott Brown, for defining and highlighting the modern cityscape—and in Heizer’s case, the modern landscape, where the built world encounters the planet. The experience of Double Negative—and, we might imagine, that of the completed City—can be compared to the approach to the Las Vegas Strip, seen first only as general forms cast in (neon) light and dark shadows of the casinos on the horizon. Like City, which relies on the easily identifiable formal qualities of “ancient” structures such as the pyramid, the buildings of the Strip casinos use well-known architectural and cultural elements as signifiers. Entering a Vegas replica of the Eiffel Tower or the Sphinx, like approaching one of Heizer’s desert works, is to abandon a certain reality of place and time, to step into visual extremes that are both real and simulated, for the sake of immersion. Neither Heizer’s works nor Vegas’ institutions are interlopers in the desert landscape; they are part of it, integrations of form and setting.

Michael Heizer, City, opening 2020

Practically speaking, Heizer’s work also offers a compelling model for a maximalist collision of “high” contemporary art and immersive, experiential fun that may eventually appeal to the Vegas culture tourist, who might be persuaded to romanticize the sweaty venture into the desert unknown that so many visitors bypass or ignore altogether (unless they’ve booked a helicopter trip over the Grand Canyon). If Las Vegas is hoping to shed the perception that it is an elaborate trompe-l’oeil, a 20th-century pleasure center for the masses, and the aging former capital of American excess and its experience economy, the city would do well to recognize that even—or perhaps especially—in the age of digital experience, its most successful cultural offerings are its most barefaced in their integration of art, commodity, risk, and drama. Perhaps the Guggenheim failed not because it was in the Venetian, but because it fought, with elitisms, against this natural union: the marriage of the consumer experience to the cultural that has always thrived in Vegas.

The Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art is enormously popular, for example, producing exhibitions such as “Picasso: Creatures and Creativity,” “Fabergé Revealed,” and “Warhol Out West” in collaboration with museums and foundations around the world. At MGM Resorts, the massive, multipurpose CityCenter complex is home to a small but staggering collection of publicly accessible works by artists including Nancy Rubin, Maya Lin, and Claes Oldenburg. Another popular museum in the city is the Neon Museum, located just north of downtown, where visitors must purchase a tour to experience the collection of restored and unrestored signage (the tours often sell out). However, a free impressive light experience—James Turrell’s Akhob (2013)—is on view in CityCenter, at least to people who know where to find it: in the Louis Vuitton store.

There is clearly the space and the appetite for museum-led projects apart from Vegas’ commercial and entertainment edifices. Produced in part by the Nevada Museum of Art, Ugo Rondinone’s Seven Magic Mountains was installed south of the city along Interstate 15 in 2016. Engaging an integrated desert aesthetics similar to those cultivated by Heizer—and by Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt, most famously in neighboring Utah—Rondinone’s stacks of brightly colored boulders take advantage of the area’s desert skies and seemingly endless, dusty-hued vistas. (The stones’ particular Technicolor might be just as easily credited to the untouched sunsets of the American southwest and to the neon of the Strip.) Like Double Negative, Seven Magic Mountains dwarfs the viewer in the expanse of the desert landscape, yet Rondinone’s work is more easily captured and consumed: as photogenic as a post card, it is land art for the Instagram era. Perhaps this quality makes it a much-needed intermediary between the Neon Museum and City: originally intended for a two-year run, the popularity of the work has organizers working to extend the project past its 2018 closing date.

[courtesy of the Neon Museum and Vox Solid Communications]

The success of Seven Magic Mountains seems to have bolstered several ambitious upcoming contemporary art projects. After a successful Zappos-sponsored residency at Art Motel—an annual activation of the that takes place during the Life is Beautiful Music & Art Festival—in 2017, the New Mexico powerhouse collective-cum-startup Meow Wolf announced a second permanent location set to open in Las Vegas in 2019. Meow Wolf Las Vegas at Area 15 will differ in theme but follow the same model as the collective’s wildly popular House of Eternal Return in Santa Fe—an elaborate psychedelic arts fun house—which leans on local artists to propose and produce colorful, multisensory, immersive installations. Meanwhile, community leaders and moneyed residents have come together to take another shot at providing Las Vegas with a purpose-built collecting museum: fundraising for the Art Museum at Symphony Park—Las Vegas’ performing arts center—is currently underway, though little else is known about what is planned.

It remains to be seen whether the city, with the assistance of Zappos and other corporate partners, can successfully build a traditional museumscape of framed works on white walls and major corporate support without sacrificing the albeit intangible local identity. And to identify that challenge is to say nothing of whether a successful museum would even contribute to developing the holy grail of the “thriving arts community” that project organizers claim to seek. Dave Hickey—best known as a prolific critic of contemporary art in general but particularly incisive on Las Vegas, having resided there on and off for almost 20 years, starting in the early 90s—has decried the costal elite who arrive in the city, already looking for “the secret Vegas,” because the delightful “secret of Vegas,” according to him, is that “there are no secrets.”11 Hickey notes the “quotidian visibility” of life in Vegas, and suggests we refer to the city as “a community with culture” as opposed to a “cultural community”—reflecting a relative lack of social hierarchies and other rigidities on which traditional art centers are so heavily dependent.12 The city’s core is its façade, and that’s okay.

[courtesy of the Neon Museum and Vox Solid Communications]

Perhaps by virtue of Vegas’ nonsecret, in this millennium the city might be an ideal site to explore solutions to the problem of how to create and market forms of culture that are accessible as well as rigorous—that, in other words, have as much capital with the tourist-consumer as they do with the traditional academic museumgoer or the status-minded contemporary collector. Vegas’ recent art successes would seem to suggest a prioritization of the consumer-at-large, status-be-damned: everyone wants some kind of bang for their buck, be it delivered by a Warhol at the Bellagio or an impressive work of land art sited in an astonishing landscape. Vegas, in this respect, teaches honesty. Meow Wolf’s photogenic funhouses have something in common with the elite art of the coasts, whose institutions have been circulating such Instagrammable exhibitions as Yayoi Kusama’s riotously popular and endlessly touring Infinity Mirrors (#infinityroom), and whose discursive and curatorial programs have undeniably taken a turn toward questions of digital technologies, their economies, and their iterations in such media as virtual reality (VR). (Jordan Wolfson’s 2017VR piece Real Violence at last year’s Whitney Biennial was one of the most talked about works in an exhibition packed with “new media,” not simply because it contained extreme violence but also because of the unsettling technology that was used to convey it.) Given this interest, it seems reasonable to suggest that a city as well-versed in the fabrication of visual and sensory experiences as Las Vegas, and as tuned in to the broad cultural appetite for immersive experience, might be looked to not as a straggler in contemporary cultural discourse but instead as a leader.

Whether Vegas is absent a “thriving art community” or home to an emerging one, what it has in abundance is a passion for fun—and wouldn’t it be a shame it that changed? If a turn of fortune were to result in a new museum, it would be because of a shift in thought not on the part of the Las Vegas community, but on the part of those elite arts audiences. American cities “between” the coasts—in that perceived cultural desert—have long heard (and made) calls for an expansion of the definition of “museum quality” contemporary art, and for a widening of the accepted places of production and engagement. As Heizer toils away in the desert largely without support from a land art-oriented entity such as Dia Art Foundation, and Meow Wolf manifests attractions so popular that they create new audiences for visual art, this expansion is happening anyway—with or without traditional institutions. With its barefaced capitalism, its visual excesses, and its aspirational spirit, Las Vegas’ nonexistent secret is that it knows itself to possess all these things. If the contemporary art world were to adopt a version of Vegas’ self-knowledge as it expands outward across the globe and inward to its local communities, we might find a way forward.

References

| ↑1 | Dave Hickey, “A Home in Neon,” Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy (Los Angeles: The Foundation for Advanced Critical Studies, 1997): 23. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Steve Izenour, Denise Scott Brown, and Robert Venturi, Learning from Las Vegas – Revised Edition (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1977): xi. |

| ↑3 | “Nevada Casinos: Departmental Revenues, 1984–2017,” Center for Gaming Research, University of Nevada, Las Vegas: gaming.unlv. edu/reports/NV_departments_historic.pdf |

| ↑4 | lasvegasweekly.com/as-we-see-it/2014/ aug/06/end-era-trifecta-gallery-closing/#/0 |

| ↑5 | emergencyartslv.com/about-emergency-arts |

| ↑6 | lasvegassun.com/guides/about/lvam |

| ↑7 | venetian.com/media/fun-facts.html |

| ↑8 | Michael Heizer, “Interview with Julia Brown,” Sculpture in Reverse (Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1984): 35. |

| ↑9 | Rosalind Krauss, “The Double Negative: a new syntax for sculpture,” Passages in Modern Sculpture (New York: The Viking Press, 1977): 280. |

| ↑10 | nytimes.com/2005/02/06/magazine/arts-last-lonely-cowboy.html |

| ↑11 | Hickey, 22. |

| ↑12 | Ibid., 21. |