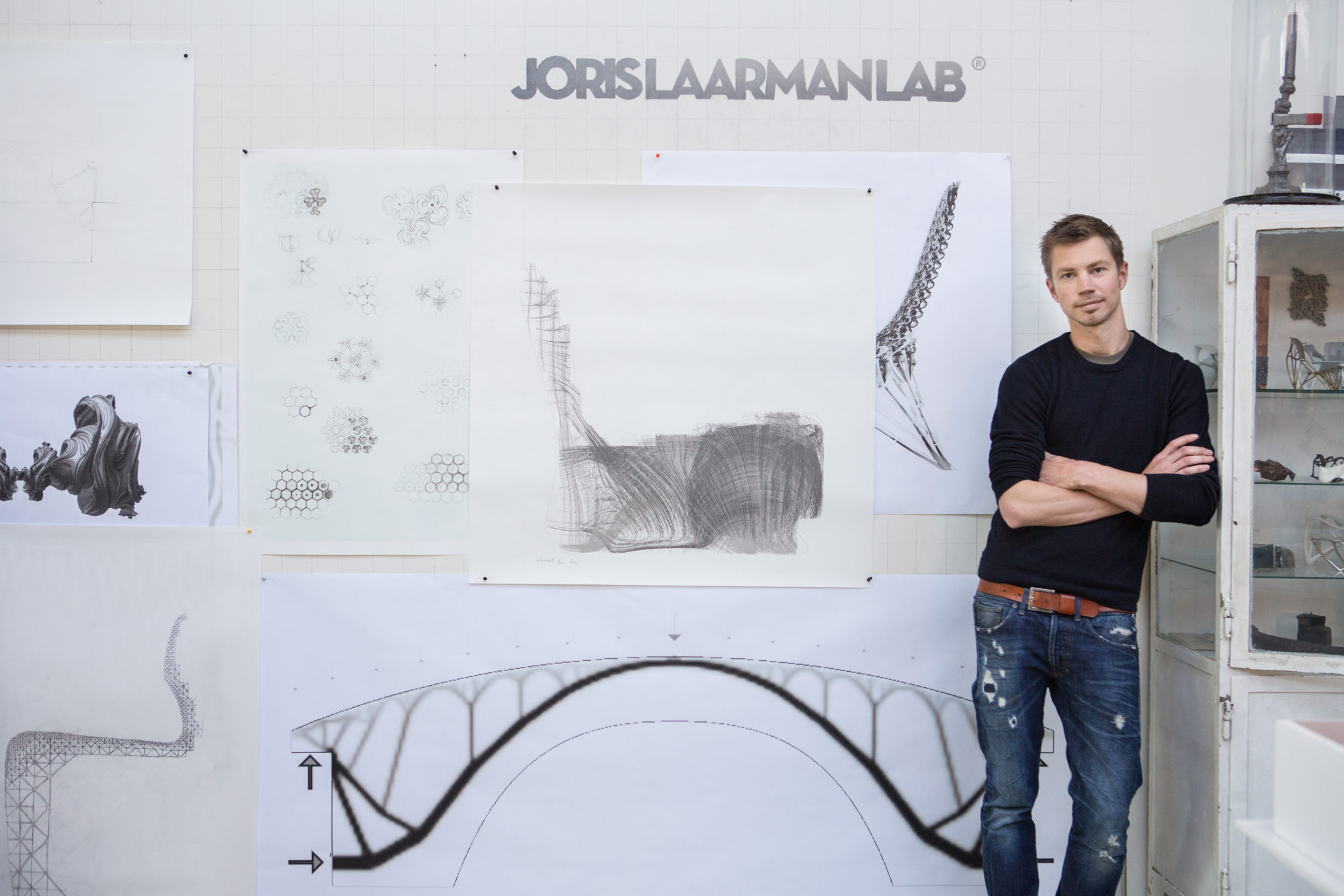

Joris Laarman [photo: Joris Laarman; courtesy of Joris Laarman Lab, Netherlands]

Joris Laarman

Share:

Atlanta’s High Museum of Art boasts the largest public collection of Joris Laarman’s work outside of the Dutch designer’s home country, and many of these holdings were featured in Joris Laarman Lab: Design in the Digital Age, a survey of innovative work spanning Laarman’s career to date. Organized by the Groninger Museum, the Netherlands, and showcased at the High Museum this spring, the exhibition presented furniture infused with digital culture—including pixelated metal tables inspired by early Nintendo games and 3D-printed Makerchairs that can be produced and assembled at home—alongside functional products such as his iconic Bone Chair, designed to mimic the growth pattern of bones and branches. Also on view were applied projects and experiments through which Laarman has explored the fusion of tradition and innovation, DIY craftsmanship and advanced technologies, and human design and the natural world.

Founded in 2004, Laarman’s Lab is known for experimental and fusional methods of fabrication, and an emphasis on interdisciplinary research and practice in the fields of science, technology, aesthetics, and ideas that make their practice one of the most groundbreaking design hubs in the world today. For this exclusive online interview, coinciding with the 2018 Atlanta Design Festival, ART PAPERS asked Laarman about reconciling the “old” and the “new,” and about the impact of design and methods of production on contemporary society and our future.

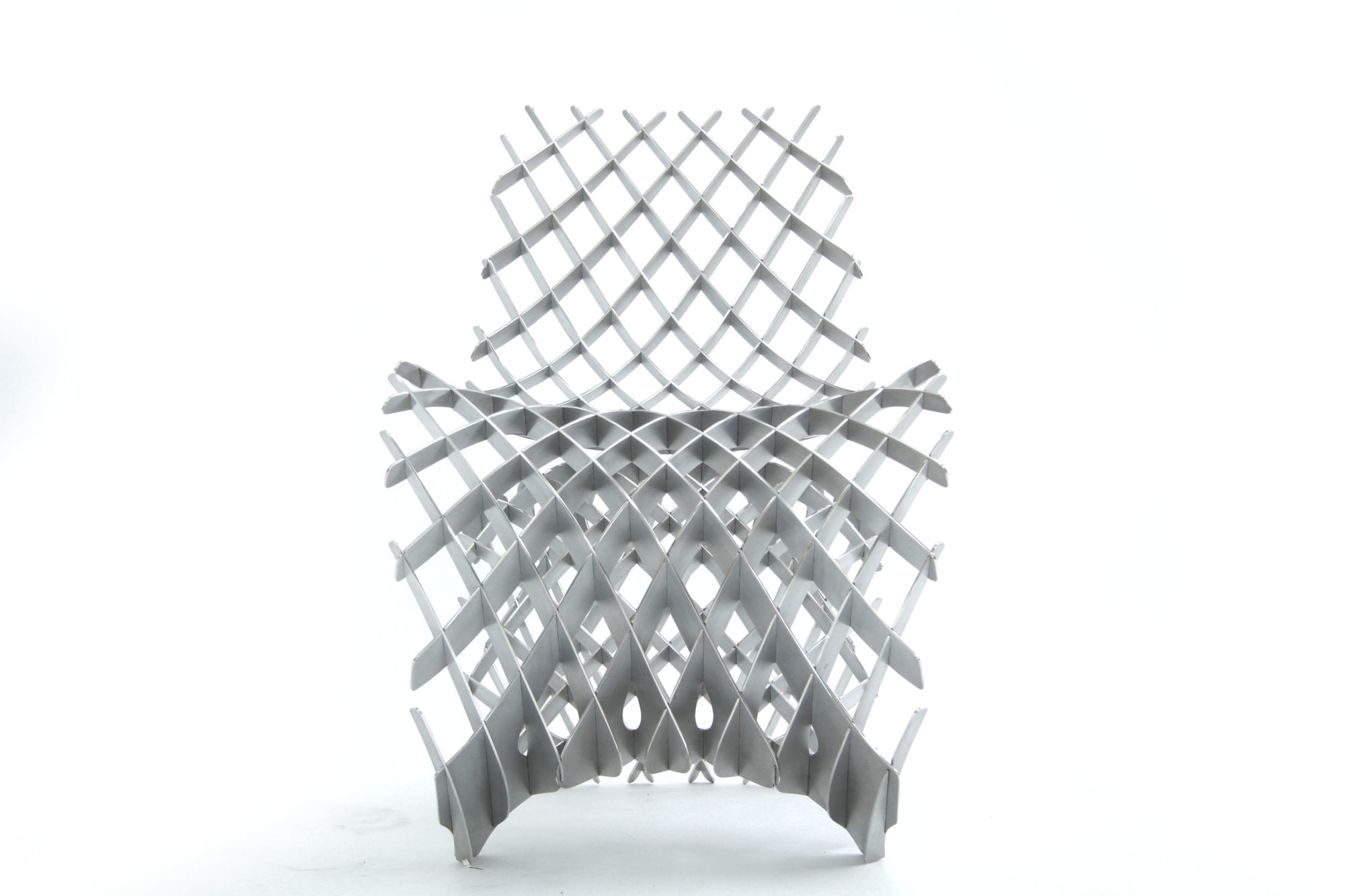

Joris Laarman, Makerchairs, 2014 [photo: Joris Laarman lab; courtesy of Joris Laarman Lab, Netherlands]

ART PAPERS: Some of your work can be downloaded and printed by anyone with access to a 3D printer or CNC router. Your website describes the idea as affordable furniture for all. How do you see the future of individualized or DIY making affecting the world of design and the world at large, socially and economically, in years to come?

Joris Laarman: I believe that in a few years you’ll find professional production workshops for DIY makers in most larger cities. In our studio we have a mix of craft educated makers from blacksmiths to woodworkers who cooperate with computer coders to develop the objects of the future. Digital fabrication brings craftsmanship into the 21st century in an efficient way. We work together with the 3D printing platform 3D Hubs, for instance, who now have more production points than McDonalds. Just to name a catchy example.

AP: MX3D is a project that sought on one level to reconcile “old” Amsterdam with the city’s present and its technological future. What do you predict for older European cities in the future, in terms of how they are designed and how they are used by their communities? What do such cities have to do to stay relevant, and to continue to evolve?

JL: I think the only thing cities should do is avoid becoming like Disneyland. We should be careful about our old buildings, and wherever something needs to be updated [we should] do it with respect. I also believe we should build for the long term, not the short. We can upgrade the old with technology to make old things smarter without harming their historic essence. Digital fabrication for instance allows the fabrication of non-standard unique forms that fit right into a not-planned, non-standardized city.

Joris Laarman, Adaptation Chair, 2014, copper and polyamide, 70 x 62 x 74 cm [photo: Joris Laarman Lab; courtesy of Joris Laarman and Barry Friedman, New York]

Everything is connected and everything is nature, whether or not [it is] biological.

-Joris Laarman

AP: With the rise of technologies that allow design and production processes to take place remotely, is there a risk of designers becoming too detached from the communities they design for, or a risk of standardizing culture?

JL: Digital fabrication allows a local approach much more than industrial fabrication does. As a designer nowadays you design things more like a program than a finished design. Everything is parametric, so highly adaptable without losing its core blueprint.

AP: You’ve mentioned in regards to your biomorphic Bone furniture that your ultimate goal was to create beautiful items with an underlying algorithmic basis. Do you view the digital work or the designed environment as distinct from, even in opposition to the natural world, or as a part of it? To what degree is your work involved in navigating this perceived contrast, or in creating a synthesis or fusion?

JL: Everything is connected and everything is nature, whether or not [it is] biological. You might argue that cultural evolution, or technology, if you like, is separating itself too much from the biological world, but I also see more and more digital design and algorithms using the same principles as found in biology.

I believe in balance, and I try to integrate nature, technology, tradition, human history, [with our] future.