John Lewis: March

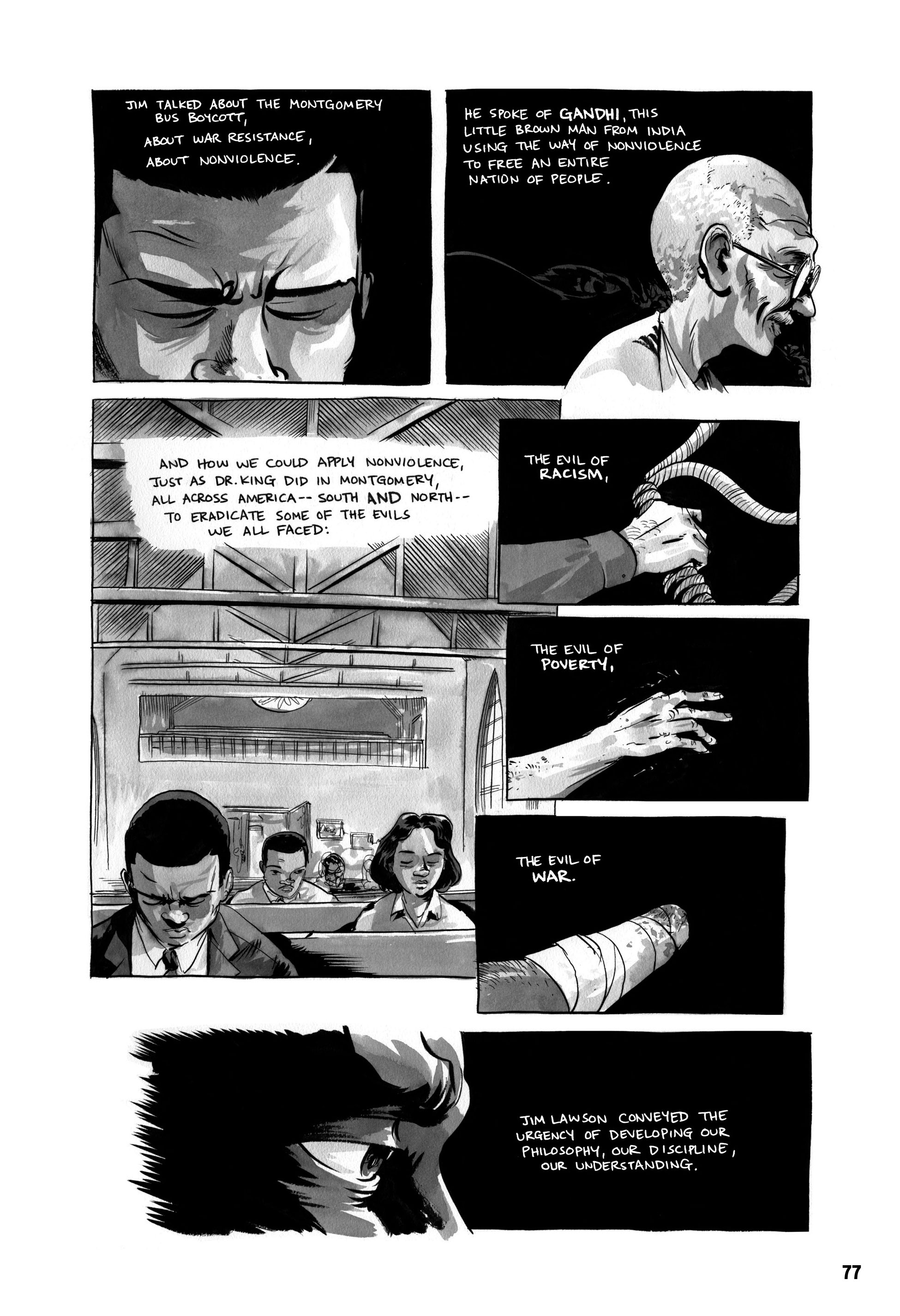

John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell, March: Book Two, 2015, interior detail 065 [courtesy of Top Shelf Productions]

Share:

Book Three of the March graphic memoir trilogy arrived in summer 2016—the season of Orlando, Brexit, Zika, the mediated dawn of the “alt-right,” and the killings of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling. In the year since its appearance, the work has only gained relevance. March is the illustrated autobiography of Georgia Congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis, and it takes inspiration partly from Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a short 1950s comic book that shows how nonviolent resistance by Rosa Parks and participants in the Montgomery bus boycott could function as tools for desegregation. Although ignored by mainstream comics companies, the Montgomery Story enjoyed grassroots distribution and popularity. Lewis’ collaborators on March were comics creator Nate Powell and Congressional aide Andrew Aydin; Aydin wrote his master’s thesis on the 16-page Montgomery Story. He also persuaded Lewis, who had already published Walking With the Wind: Memoir of the Movement (1998), that comics was a compelling medium for this firsthand account of the Civil Rights Movement. What would underpin the narrative, however, were strategies for action, boldly illustrated. In a technical sense, their collaboration is lucid and digestible: Lewis’ words are direct, and Powell’s illustrations make the events they describe particularly accessible. It’s one thing to read about the Freedom Riders’ bus going up in flames, but another to see a rendering of it. In addition to Lewis’ early civil rights contributions, the trilogy depicts political leaders such as Diane Nash, and, of course, the “Big Six”; the illustrations put faces to these important names.

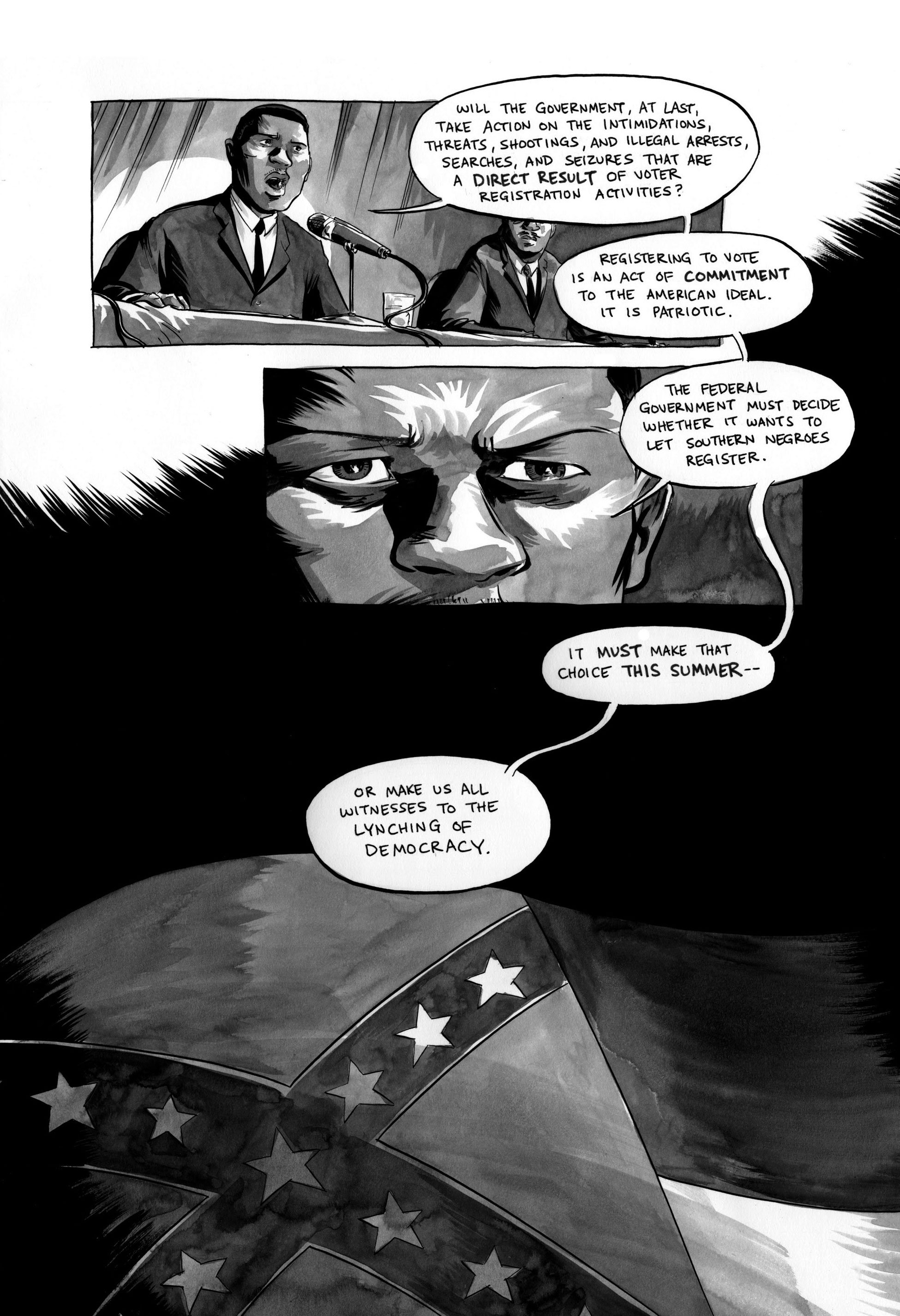

Left: John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell, March: Book One, 2013, interior detail [courtesy of Top Shelf Productions]. Right: John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell, Lynching of Democracy, March: Book Three, 2016, interior detail [courtesy of Top Shelf Productions]

March begins with Lewis’ early life in Pike County, AL—where he took care of his family’s chickens, building them an incubator, preaching to them, even baptizing them. As a young boy, in 1951, Lewis took a trip to New York with his Uncle Otis; this glimpse into the world outside the South changed him: “After that trip,” he writes, “home never felt the same, and neither did I.”

The rest of the trilogy follows Lewis’ early life as a civil rights activist, covering his response to the death of Emmett Till in 1955 and his endorsement of the signing of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. March follows Lewis as he embarks with the first group of Freedom Riders, is elected chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and later organizes what would become the infamous march on Selma. After a relatively gentle entry into the trilogy through Lewis’ early life in Alabama, the authors pull back the curtain on the horrific violence of the South—graphically. Hard-to-digest, necessary history lessons are punctuated by tender moments in the series; in Book Three, Lewis dances the night away with Shirley MacLaine at a SNCC party in Atlanta. Such moments function as brief, humane pauses amid the nightmare of Jim Crow.

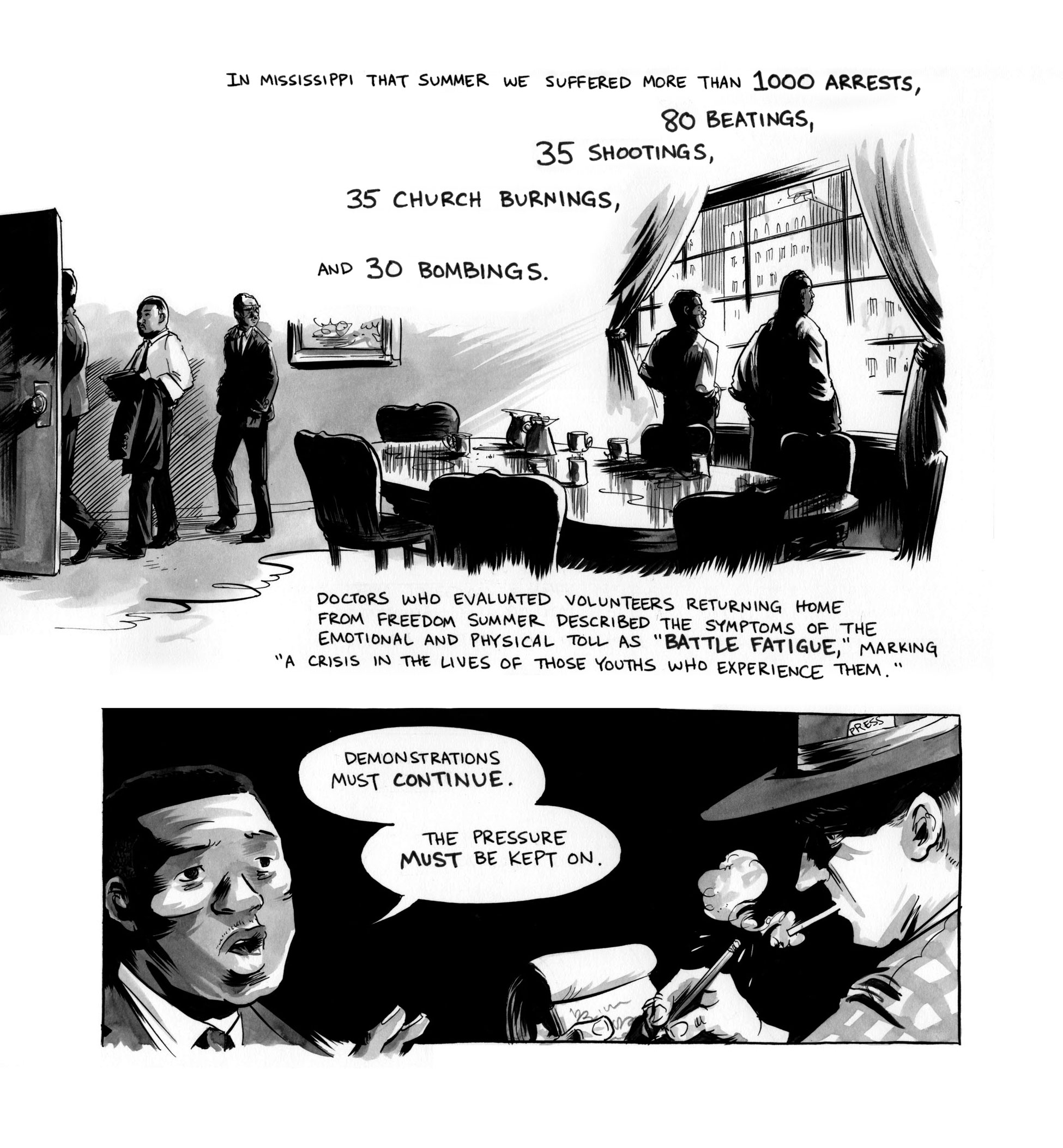

March’s violence escalates between Book One and Book Two, the latter of which contains some of the trilogy’s most jarring scenes. When the Freedom Riders arrive in Montgomery, AL, they are immediately attacked by a mob of angry white people who had been waiting for them with intent to kill; Powell’s visceral images portray one attacker whose hands drip with blood as he yells, with a smile, “Git him! Them eyes, get them eyes!” Elsewhere we see so-called Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Connor blasting children with firehoses in Birmingham, while commanding his dogs to attack. Book Three opens with the clik, clik, clik of heels on a church floor—a woman en route to check on four little girls getting ready for Sunday school in the bathroom of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church—a haunting prelude to the racist bombing that shocked the nation in 1963, and one of the most evocative moments of the series. The scenes of brutality—and there are a lot—never feel unnecessary or exploitative. March doesn’t use violence for shock value—which would be inconsistent with Lewis’ nonviolent advocacy—but instead reveals an unfiltered history of postwar American society.

John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell, Demonstrations Must Continue, March: Book Three, 2016, interior detail [courtesy of Top Shelf Productions]

Although the bulk of the series is set within the early Civil Rights Movement, March sets up another story: the trilogy begins within the framework of President Obama’s 2009 inauguration; between the scenes of hate crimes, organized protests, and internal and intergenerational conflicts within such organizations as SNCC, we get flashes forward, into the 21st century. At first, this refrain, which punctuates Lewis’ life as an activist with visions of our first black president, seems to signify a kind of happy ending. Reading the book in 2017 proved especially disquieting, though, aware as we are of how far our reality is from the myth of the post-racial society, or from the end of white supremacy. The trilogy’s dedication to “the past and future children of the movement” is an acknowledgment of that distance, and perhaps also an imperative. March is a historical case study: Lewis wants to educate the public about a moment in time, not simply so that current and future generations may have access to an unfiltered account of the Civil Rights Movement, or to memorialize its victories, but also to provide a method for action—an illustrated guide. If Lewis wants copies in libraries, high schools, and universities, it is not because he is feeling triumphant; it is because he knows, as many Americans do, that the fight is ongoing. March is a not a memoir; it’s a manual.