Artists Books from The Atlanta School

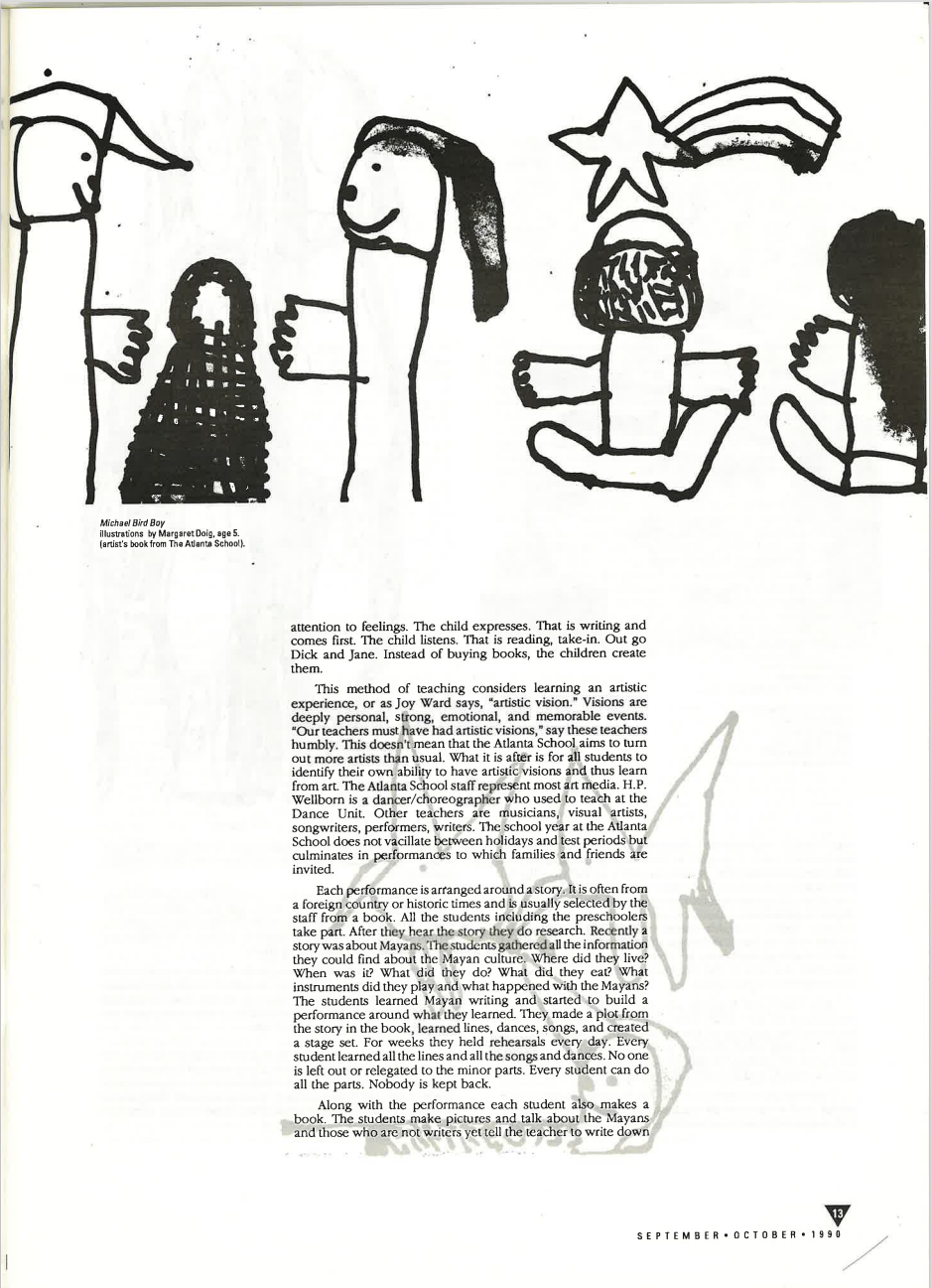

Michael Bird Boy, Margaret Doig, 1990 [courtesy of The Atlanta School]

Share:

In recent decades much attention has been given to a child’s ability to identify basic geometric shapes and the colors. Until those skills were mastered a child was not thought to be able to read and write. In other words, a connection between visual and abstract thinking has been assumed. There is undoubtedly a relation between art and literacy. But does it start with geometry? The basic geometric figures are the square, the triangle and the circle. None of these is actually prominent in our alphabet. “O” is usually printed as an oval. Nobody writes “a” by first making a triangle and then extending two sides to be longer lines. Foreign alphabets include fewer basic geometric figures. Still, Arabic, Chinese, Sanskrit and Hebrew, for example, have been taught successfully to children for many hundreds of years.

Are literacy and visual art possibly connected through content? Do topics motivate humans to read?

It’s a rare child who spontaneously starts to design squares and triangles. Ask children to draw family members, a pet, or a car and you will get a better response. They will do that even if you don’t ask them.

So what’s new? When children start to draw they will miss some details. A face will lack eyebrows or a nose. Then you point out to the child that faces really have noses and eyebrows, some even beards, and the child will agree and probably add those details. The picture will get better. A little later the child may disappoint you and point at the same picture and claim that it is not a picture of Mom but of a friend. You have no reason to worry. The child looks at the picture and talks about it and that’s what you want. We start to read that way.

At the Atlanta School, for preschool through fourth grade, founding teachers Joy Ward and H.P. Wellborn teach reading from words they identify as important to the individual child. They believe that reading is mental intake. Writing is giving. To teach you must get to know the child, particularly paying attention to feelings. The child expresses. That is writing and comes first. The child listens. That is reading, take-in. Out go Dick and Jane. Instead of buying books, the children create them.

This method of teaching considers learning an artistic experience, or as Joy Ward says, “artistic vision.” Visions are deeply personal, strong, emotional, and memorable events. “Our teachers must have had artistic visions,” say these teachers humbly. This doesn’t mean that the Atlanta School aims to turn out more artists than usual. What it is after is for all students to identify their own ability to have artistic visions and thus learn from art. The Atlanta School staff represent most art media. H.P. Wellborn is a dancer/choreographer who used to teach at the Dance Unit. Other teachers are musicians, visual artists, songwriters, performers, writers. The school year at the Atlanta School does not vacillate between holidays and test periods but culminates in performances to which families and friends are invited.

Each performance is arranged around a story. It is often from a foreign country or historic times and is usually selected by the staff from a book. All the students including the preschoolers take part. After they hear the story they do research. Recently a story was about Mayans. The students gathered all the information they could find about the Mayan culture. Where did they live? When was it? What did they do? What did they eat? What instruments did they play and what happened with the Mayans? The students learned Mayan writing and started to build a performance around what they learned. They made a plot from the story in the book, learned lines, dances, songs, and created a stage set. For weeks they held rehearsals every day. Every student learned all the lines and all the songs and dances. No one is left out or relegated to the minor parts. Every student can do all the parts. Nobody is kept back.

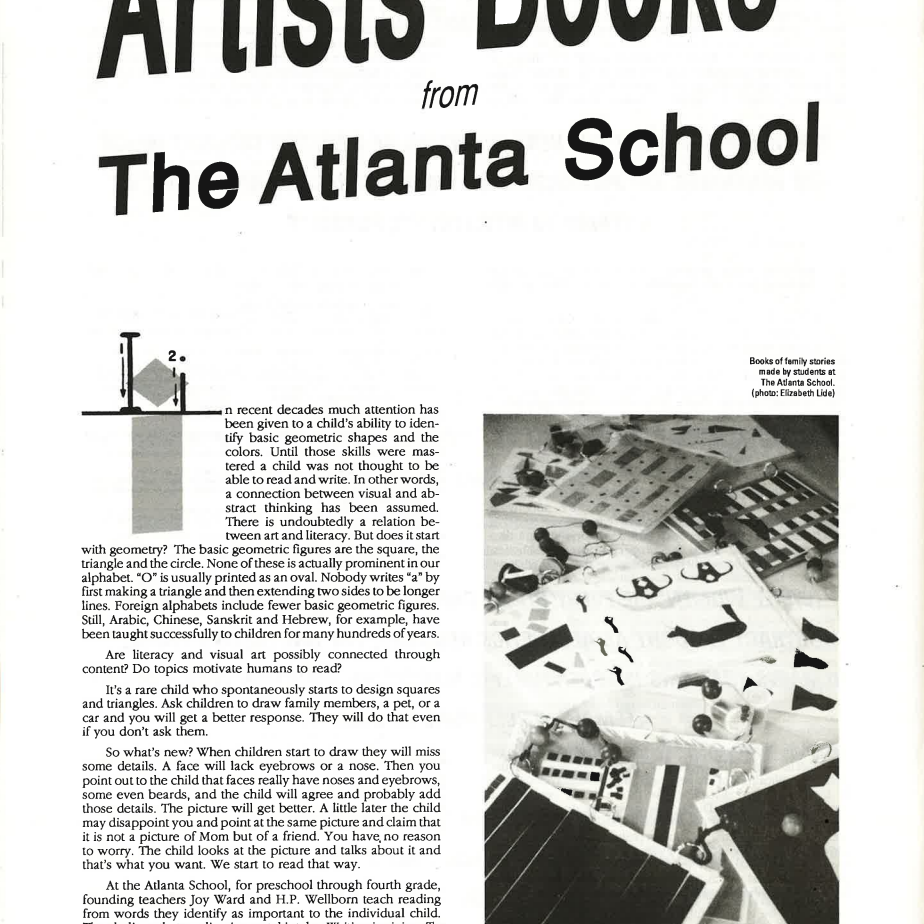

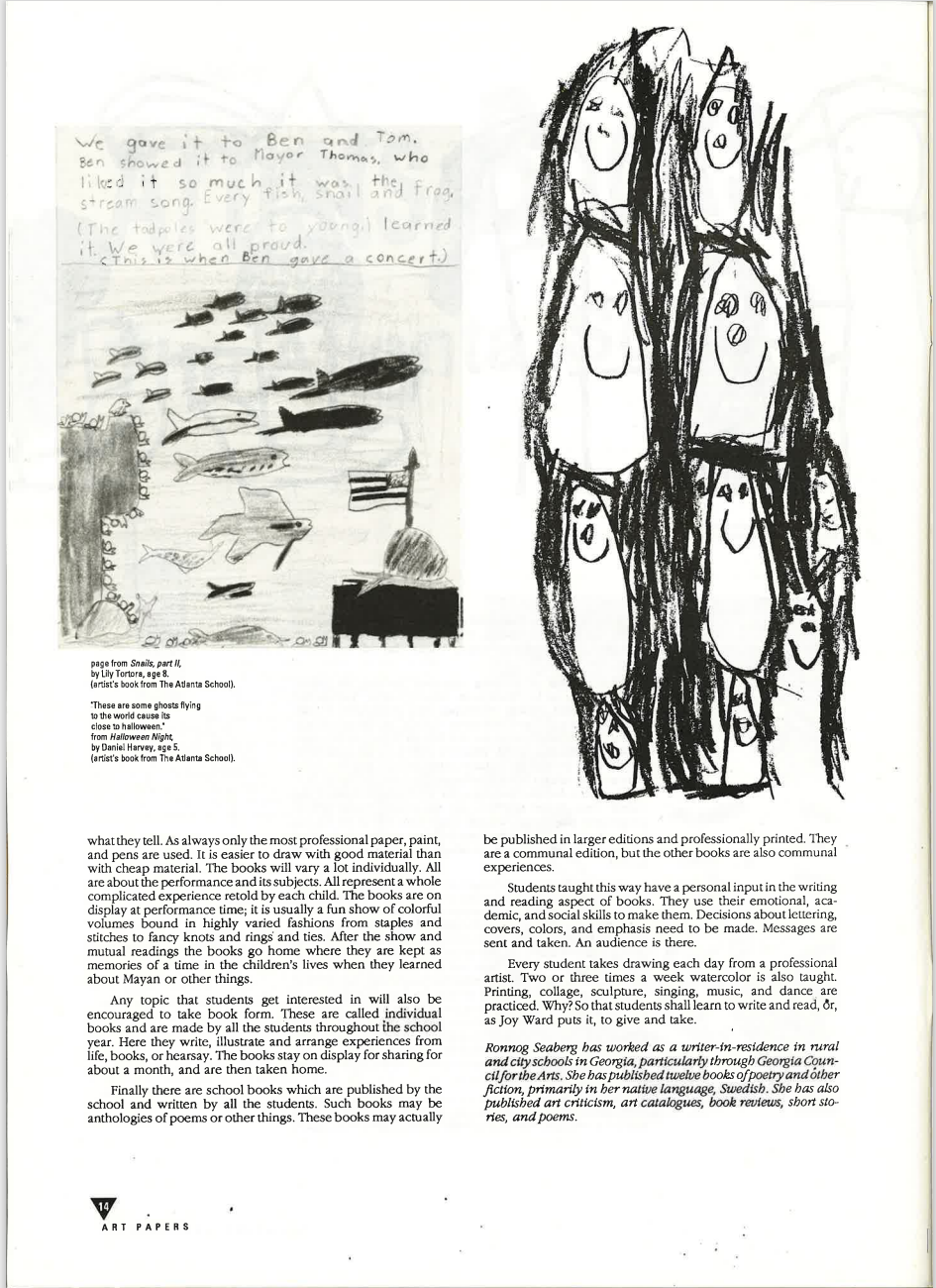

Along with the performance each student also makes a book. The students make pictures and talk about the Mayans and those who are not writers yet tell the teacher to write down what they tell. As always only the most professional paper, paint, and pens are used. It is easier to draw with good material than with cheap material. The books will vary a lot individually. All are about the performance and its subjects. All represent a whole complicated experience retold by each child. The books are on display at performance time; it is usually a fun show of colorful volumes bound in highly varied fashions from staples and stitches to fancy knots and rings and ties. After the show and mutual readings the books go home where they are kept as memories of a time in the children’s lives when they learned about Mayan or other things.

Any topic that students get interested in will also be encouraged to take book form. These are called individual books and are made by all the students throughout the school year. Here they write, illustrate and arrange experiences from life, books, or hearsay. The books stay on display for sharing for about a month, and are then taken home.

Finally there are school books which are published by the school and written by all the students. Such books may be anthologies of poems or other things. These books may actually be published in larger editions and professionally printed. They are a communal edition, but the other books are also communal experiences.

Students taught this way have a personal input in the writing and reading aspect of books. They use their emotional, aca- demic, and social skills to make them. Decisions about lettering, covers, colors, and emphasis need to be made. Messages are sent and taken. An audience is there.

Every student takes drawing each day from a professional artist. Two or three times a week watercolor is also taught. Printing, collage, sculpture, singing, music, and dance are practiced. Why? So that students shall learn to write and read, or, as Joy Ward puts it, to give and take.

Ronnog Seaberg has worked as a writer-in-residence in rural and city schools in Georgia, particularly through Georgia Council for the Arts. She has published twelve books of poetry and other fiction, primarily in her native language, Swedish. She has also published art criticism, art catalogues, book reviews, short stories, and poems.