Jill Magid: Between Words and Deeds

Share:

This interview was originally published in ART PAPERS March/April 2012, Vol. 36, issue 2.

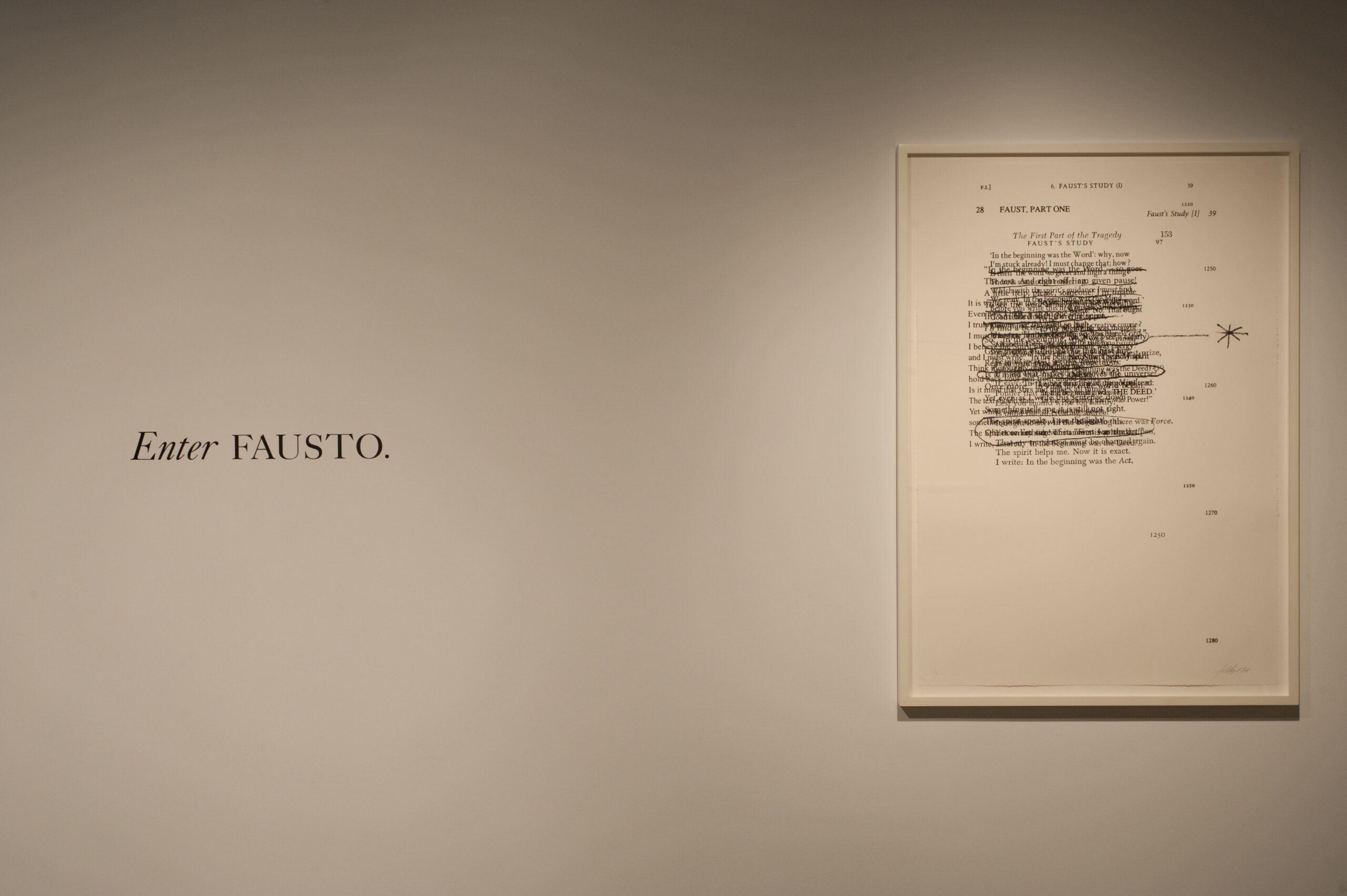

Jill Magid, installation detail of Failed States, 2012: Stage Direction: Enter FAUSTO, 2011-2012, vinyl on wall, dimensions variable; The Deed, 2011, silkscreen on paper, 45 x30 inches, [courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City]

Jill Magid’s exhibition Failed States is rooted in present-day events as they intersect with governmental power [Arthouse, Austin, TX; January 14 — March 4, 2012]. In January 2010, Magid witnessed a mysterious shooting on the steps of the Texas Capitol building. Nothing is known of Fausto Cardenas’ motivations, but his gesture of shooting into the sky from the Capitol steps — in full view of security — reads as a tragic and poetic dramatic act. For this project, Magid connects Fausto’s action to Goethe’s Faust, originally written as a “closet drama,” a kind of intimate reading that functions as a theater of the mind. In Faust, Magid finds both thematic connections and a form of performative exhibition.

Jill Magid: Closet Drama, the exhibition’s first iteration, was presented at the Berkeley Art Museum (BAM) as a part of their MATRIX Program [March 20 — June 12, 2011]. Failed States, its second version, includes an armored car and the publication of a text written by Magid in a local magazine. In this interview, which preceded the exhibition’s opening, Magid talked with Noah Simblist about the project’s complex web of narratives, including Fausto and Faust, her training to become an embedded reporter, the relationship between words and action, and the role of interpretation in both the fantasy of literature and the concrete reality of lived experience.

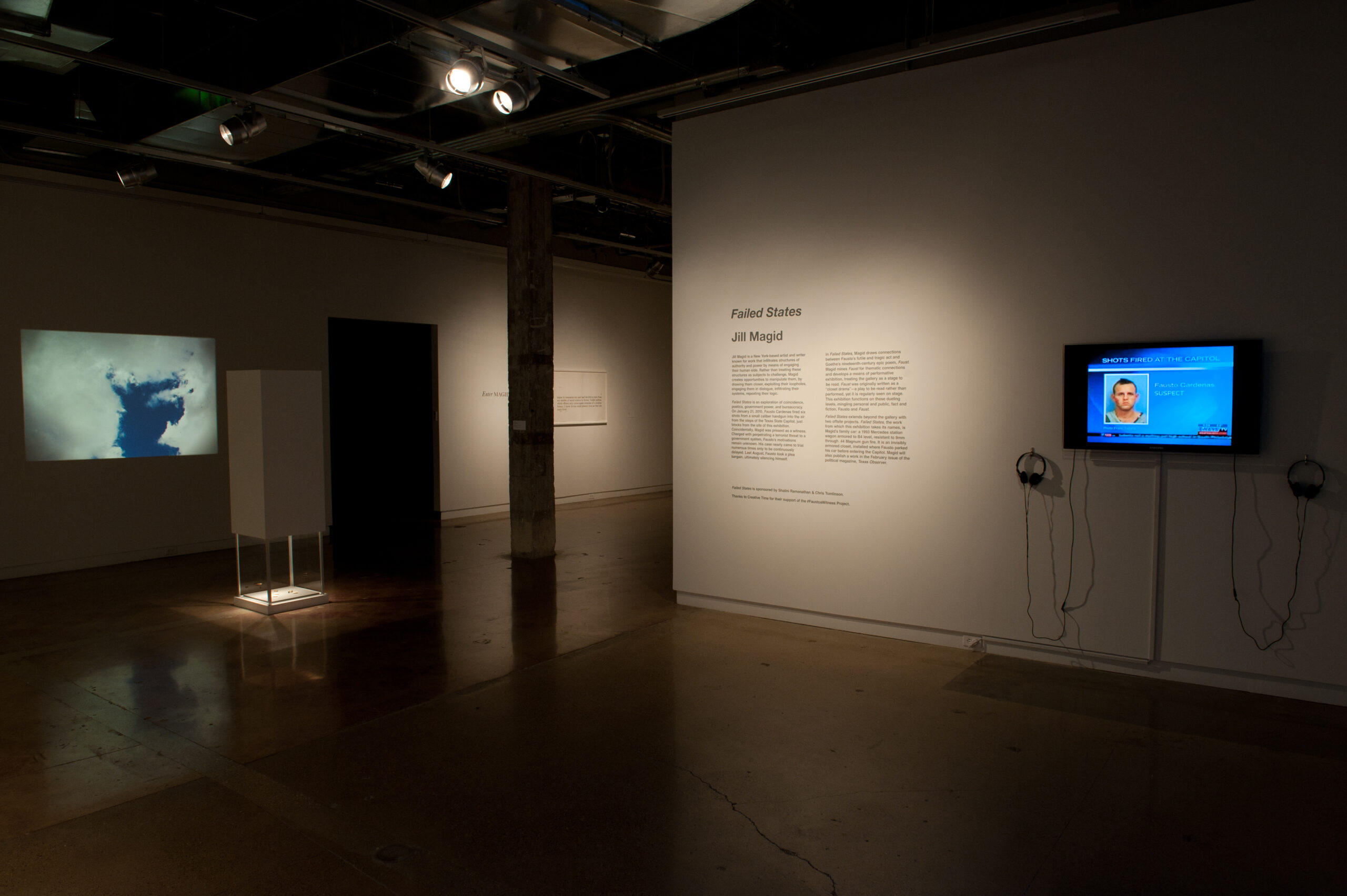

Jill Magid, installation detail of Failed States: Six Shots from the Capitol Steps, 2012; Six Shots from the Capitol Steps, 2012; middle: Fiction, 2011, silkscreen on paper, 27.25 x 44 inches, [courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City]

Jill Magid, The Capitol Shooter: Breaking News, 2011, archived news footage, 9:15 minutes; Jill Magid, Installation detail of Failed States, 2012; Exit, 2011, archival digital prints on paper, diptych: 42 x 27.29 inches, [courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City]

NS: How did you begin working on Closet Drama and Failed States?

JM: My interest in sniping and intimacy came together coincidentally in Austin. I was searching for a place to begin and it found me. That hadn’t really happened to me before; I’d always had to discover an entry point. I was commissioned by Arthouse to make a new work. At the time, I had finished The Spy Project, 2005-2010, which originally began as a commission from the Dutch secret service. I had just completed my research for A Reasonable Man in a Box, 2005-2010, my solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in which I was investigating torture and its legal language. I noticed that torture, and other military activities such as sniping were sometimes referred to as “intimate” in the press.

NS: Why would they use that term?

JM: Torture is, generally, a relationship between two people. I think that the term “intimacy” is intended to describe the intensity and physicality of this one-on-one relationship, but it bothered me. An article in the New York Times referred to the intimacy between a sniper and his target, as observed through the sniper’s lens. I wondered, does intimacy require a two-way relationship? There are levels of intimacy, of course. In Evidence Locker, 2004, I explored a similar relationship through police surveillance cameras. I looked back at the camera operators and engaged them; I asked them to watch me, even directing how they filmed me. I’m interested in the romanticism of being above and looking down, of quietly observing those below. But in the case of a sniper, that observation leads to the firing of a bullet.

Since my commission was to take place in Austin, I decided to explore sniping. I would first visit the clock tower at the University of Texas where Charles Whitman killed several people in 1966. On my way to the tower, I visited the Texas Capitol. While I was there, I witnessed a shooting.

NS: But it’s the reverse because, as I understand it, this man was shooting up from below.

JM: Yes, he was shooting up into the sky. It was an absurd, fatalistic act, like Chris Burden’s 747,1973, but without the plane.

NS: I wonder if you could go into more detail about the shooter and his story.

JM: Not much is known about him, besides police reports and court records — I have all of them, in addition to what was published in the newspapers. The story goes like this: he drove from Houston to the Capitol, parked his car, went up to the third floor, where he saw “a woman in a white shirt” — a senator’s legal aide — and followed her into the senator’s office. Inside, he asked to speak to the woman privately. She refused repeatedly, so he left. Then he walked out onto the front steps and shot six rounds into the sky — and I was there, as a witness. I found out that his name was Fausto. The Capitol is such a theatrical place and Fausto used its steps as a platform to shoot up to the sky, like a stage.

Jill Magid, Failed States, 2012, Armored Car, Installed at the Capital, [courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City]

NS: I understand that you first made works about this incident for your MATRIX exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum last year. Was your show Closet Drama all about Fausto?

JM: The BAM show explored Fausto in relation to Goethe’s Faust

NS: Some interpretations of Faust tease out a Christian narrative, right? Wasn’t Goethe’s Faust less Christian than Marlowe’s?

JM: I have not read Marlowe’s yet, but I’ve read about six translations of Goethe’s. For a while, I tried to suppress my desire to read Faust in relation to Fausto — it seemed like such a silly link. But I finally gave in, which was good, because I kept finding inspiring connections between the drama and the real story. For the exhibition, I focused on one of Faust’s monologues in which he wants to translate the Bible into German. He reads, “In the beginning was the word,” but then says no, that’s not right. “The Word,” he says, should be replaced with “the Deed.” Faust was an old, learned man with multiple PhDs, but he wanted to feel life viscerally. So he relinquishes words for action. Fausto had tried to speak, but was denied. Instead he fired a gun into the air. Both men reached for the heavens — figuratively (Faust) and literally (Fausto), and both fell, with tragic consequences.

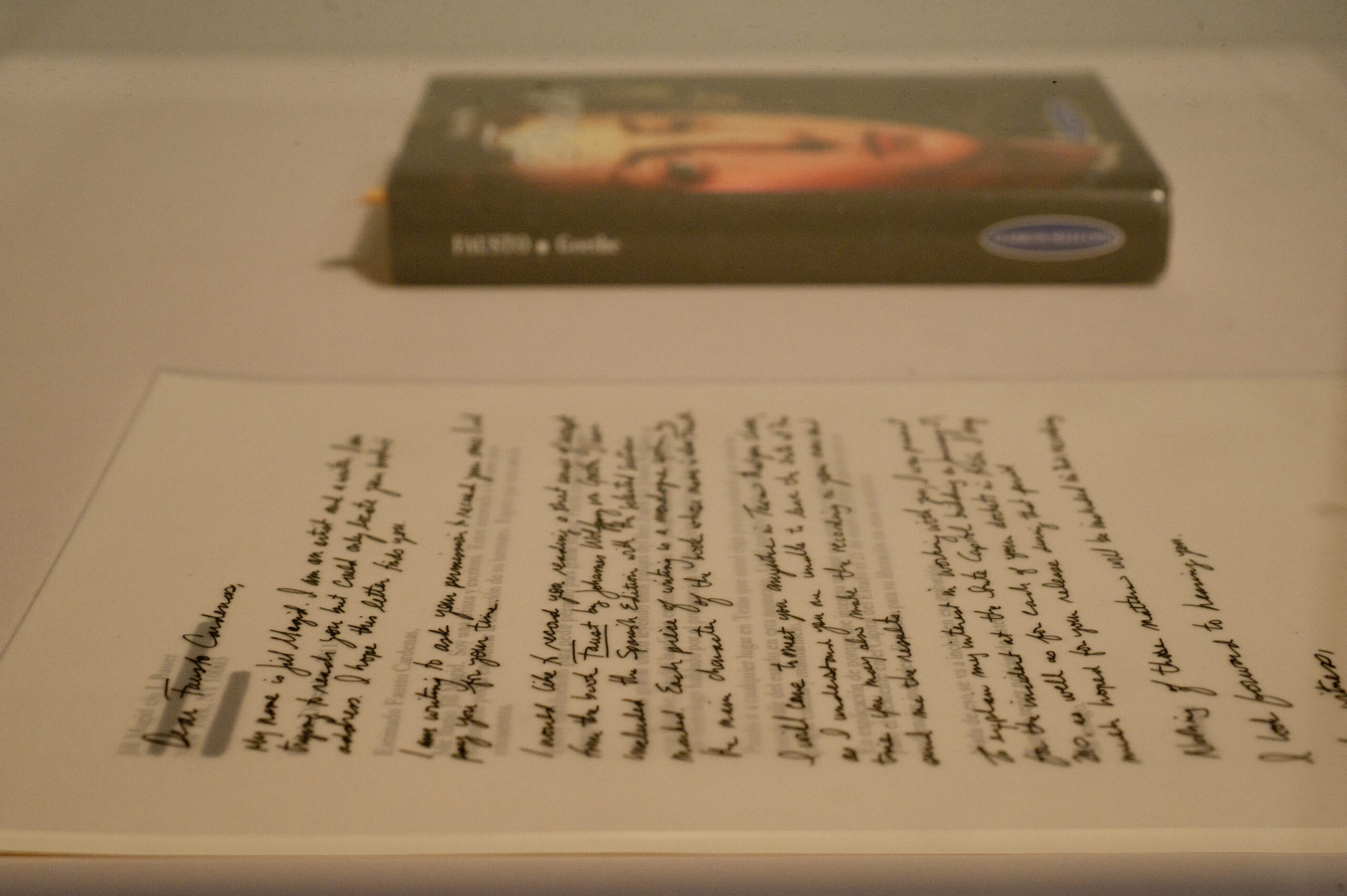

Jill Magid, Fausto, vitrine, 2012, marked book, letter to Fausto Cardenas, facsimile of letter and Spanish translation, [courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City]

NS: That’s so interesting. People usually refer to Faust in terms of his deal with the devil, but this is another angle. Did you consult Faust experts to learn more about various interpretations of the story? Did they agree with your link between Faust and Fausto?

JM: I contacted a young German professor at the University of Texas — a literary expert, who was organizing a performance of Faust. I asked him to deconstruct the Faust/Fausto relationship with me. At first, I could tell that he thought it was sort of ridiculous — or maybe I was. But once we met, he got into it as much as me. We began wondering, for example, who was Gretchen in the Fausto story? He speculated that I was the devil. So that’s a chapter in the novel Failed States. It incorporates Fausto and a parallel narrative about this professor and our intense, kind of sexually charged meeting. I later filmed him in his study reading Faust to me, and used that footage in the Berkeley show.

NS: What works were in the BAM show? How did you visualize this connection?

JM: The title of the show was Closet Drama. Fausto was originally written as a closet drama — I love that term. It’s a kind of intimate reading, to oneself or a small group — a theater of the mind. I treated the gallery like a stage to be read. I used vinyl on the wall as stage directions to lead the viewer through the space and narrative. Goethe’s monologue on words becoming deed is both a sound work and a silkscreen. I mixed in news footage of my role as a witness to Fausto’s shooting, and had a live feed of the sky above the capitol steps. I wrote a poem, Fausto, A Tragedy, 2011, and displayed it as a leaflet.

NS: How will the Austin show be different?

JM: At the time of the Berkeley show, Fausto was still in jail awaiting trial. He’d been accused of a terrorist threat against a government institution. This August, he took a plea deal. I was there for that and all of his previous dockets. The Austin show will have many elements from Berkeley, but they will be transformed and extended, with new pieces added. The emphasis will be on Fausto’s silence. He never explained his intentions — in the senator’s office or before the judge. I found a beautiful Spanish translation of Faust — titled Faustol — whose cover is illustrated with a portrait of a young man about Fausto’s age. I will display it with a letter I wrote to him, asking him to read specific passages of Faust to me.

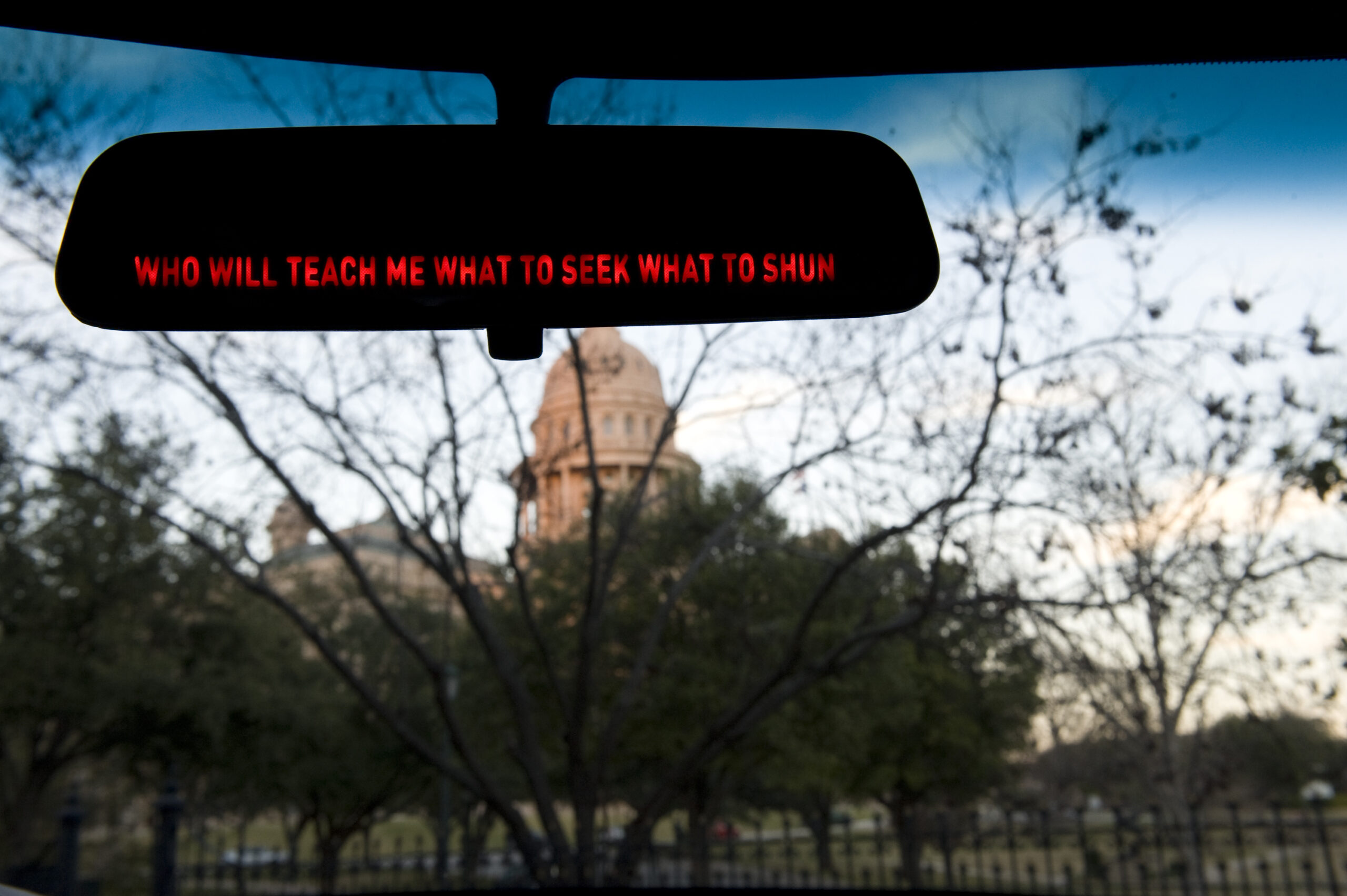

A major addition is two offsite works: Failed States and a text for the Texas Observer. Failed States is the title for my used 1993 Mercedes station wagon, which will have been armored to B4-level resistance. It’s an invisibly armored family car — as well as an armored closet. A version of the sound work, The Deed, 2011, will play from its radio, and phrases from Faust will be etched into its mirrors. The car will be parked at the Capitol in the spot where Fausto parked his car on the day of the shooting. While Fausto has largely been forgotten in Austin, the effect of his deed has not. Since the shooting, the Capitol has spent over three million dollars arming itself, outfitting its guards with M4S and placing metal detectors at the entrances.

Jill Magid, detail of Six Shots from the Capitol Steps, 2012, slide projection, amplified sound, six empty bullet shells, 68 x 18.75 x 18.75 inches, [courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City]

Jill Magid, details of Failed States, 2011, [courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City]

Jill Magid, details of Failed States, 2011, [courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City]

Also titled Failed States, my book revolves around Fausto and a parallel narrative, in which I explore my position as witness differently — also in Austin, but beginning with the shooting and ending with the plea deal. My research on sniping had led me from Fausto to another man — CT (real name withheld), the then-managing editor of the Texas Observer and a former war reporter who had been embedded with the US military in Iraq and Afghanistan. He trained me to be an embedded journalist in Afghanistan, with the idea that I would write a story from there for the Texas Observer. The actual piece for the Observer will be a series of excerpts from Failed States that focus on driving — literally (the car) and figuratively (the story).

Jill Magid, Failed States, 1993 Mercedes Benz 300TE station wagon armored to B4 level, 2011, resistant to 9mm through .45 Magnum gunfire, [courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City]

NS: You mentioned that you want to “embed” the book in the Texas Observer — what do you mean by that?

JM: I first proposed to the Texas Observer that they publish my entire book — about 45,000 words — in their magazine. I liked the idea of the seamless incorporation of the book into that particular magazine, at least visually. I also liked the notion of staging a takeover of a political magazine with a voice that would stray from the audience’s expectation. I also love the name — Texas Observer — because I felt like I’d become an observer, albeit not in a journalistic sense. The Observer came back with limitations — about the number of words, the form, and the font! At first I was upset — I still am in some ways — but I also realized that that’s what embeddedness means, working within the constraints of the system. I’m still pushing to be placed in a section other than Culture.

NS: Can you describe #FaustosWitness, 2011, the Twitter project that you did for Creative Time?1 You were acting like a court reporter, right? It seems to expand the writing component of the project, beyond journalism, and the novel and poem we’ve discussed.

JM: I’d never tweeted before! Creative Time wanted to commission me to do a project on Twitter. I thought that it made a lot of sense to tweet about Fausto’s trial. In August 2011, after eighteen months in jail, he was finally going to trial.

I tweeted about the hearing, my feelings and observations in real time from the courtroom. The tweets were like my notes. Fausto took a plea deal before the trial actually began. I think that most of the people following the case and my tweets might have found that disappointing. At the time, I did too. Ultimately, however, it’s kind of the perfect ending. When he took the plea deal, I called my friend. I was all upset. She asked, “What would you have wanted to happen, some dramatic ending?” That was a good question. It made me really think about what actually did happen, and the meaning of tragedy.

NS: It seems that much of your work is about the relationships that you build with people. In Closet Drama, both Fausto and CT are figures with whom you develop some kind of sustained relationship. Even though you’ve never spoken with Fausto, you watched him and followed his fate through the trial. How does the training and the relationship with CT relate to your previous work such as Lincoln Ocean Victor Eddy (L.O.V.E), 2007, for instance?

JM: There’s certainly a recurring theme here. In L.O.V.E, I asked a cop in post 9/11 New York to train me in the subway system at night. And in The Spy Project, I was inadvertently trained to be an agent handler by all the agents I met, but most affectingly by my favorite spy, the head of counter-terrorism. I think I seek out these types of relationships. When I first met CT, I felt like he was this rogue version of my favorite spy. It seemed like fate. He’d been in the NSA, and then he’d become an embedded war reporter. I wondered, is that supposed to be what I do too? So I followed him, or tried to make him lead me. I think our relationship was less about love than L.O.V.E. and more about being lost, or trying to be embedded. Each relationship, though, has been unique, and largely affected by its context. They’re also influenced by where I am in my life.

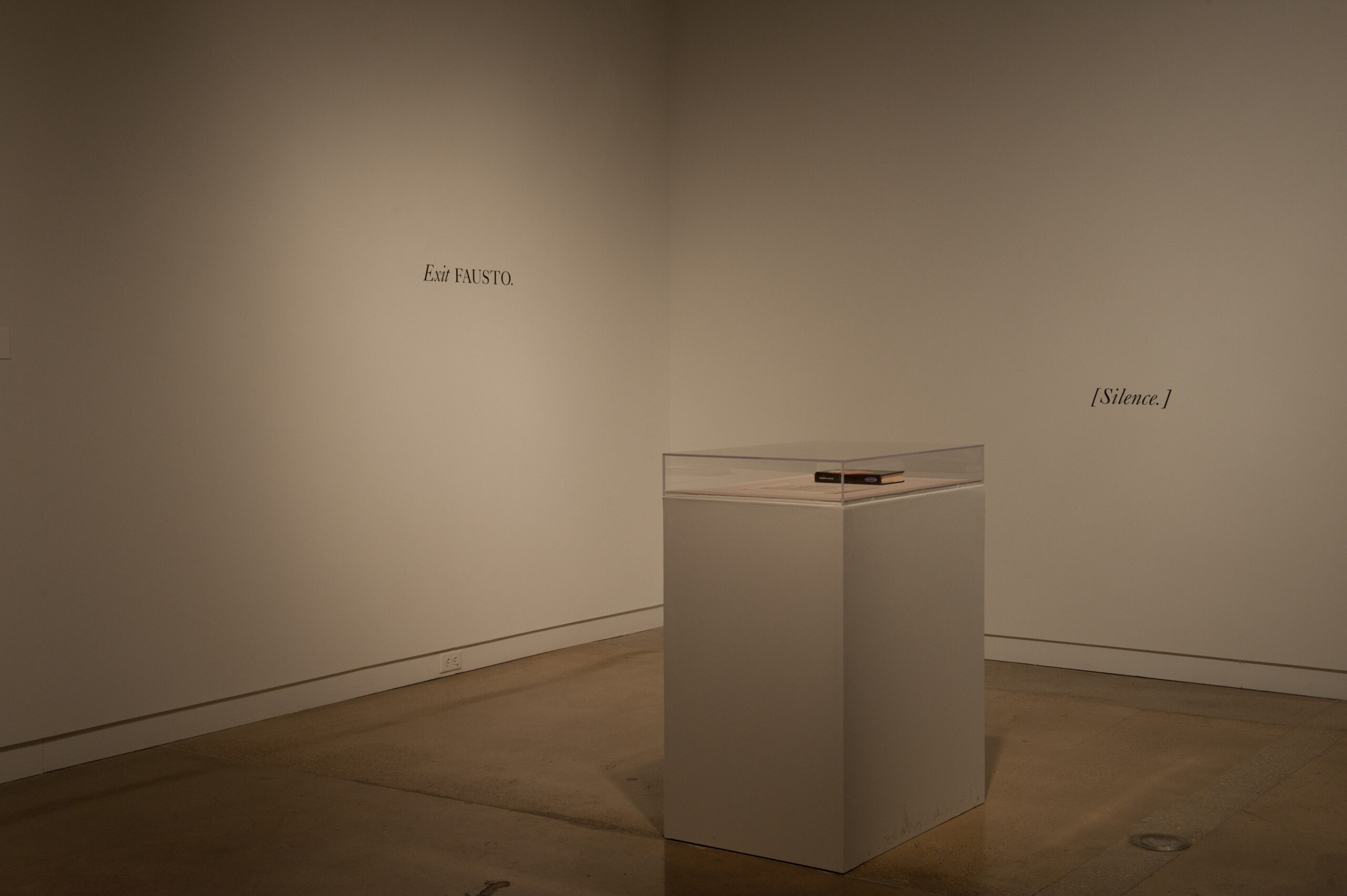

Jill Magid, installation detail of Failed States, 2012: Stage Direction: Exit FAUSTO, [Silence], 2011-2012, vinyl on wall, dimensions variable; center: Fausto, 2012, vitrine, marked book, letter to Fausto Cardenas, facsimile of letter and Spanish translation, [courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City]

Noah Simblist works as a curator, writer, and artist with a focus on art and politics, specifically the ways in which contemporary artists address history. He has contributed to Art in America, Modern Painters, Terremoto and other publications. He is the co-curator of Commonwealth, a multi-year project exploring the notion of the commons at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University in partnership with the Philadelphia Contemporary and Beta Local in San Juan. He is also Chair of Painting + Printmaking and Associate Professor of Art at Virginia Commonwealth University.

References

| ↑1 | Transcript of #FaustosWitness accessible at http://creativetime.org/programs/archive/2011/tweets/?=384 |

|---|