Jes Fan: Infectious Materials, Molecular Memories

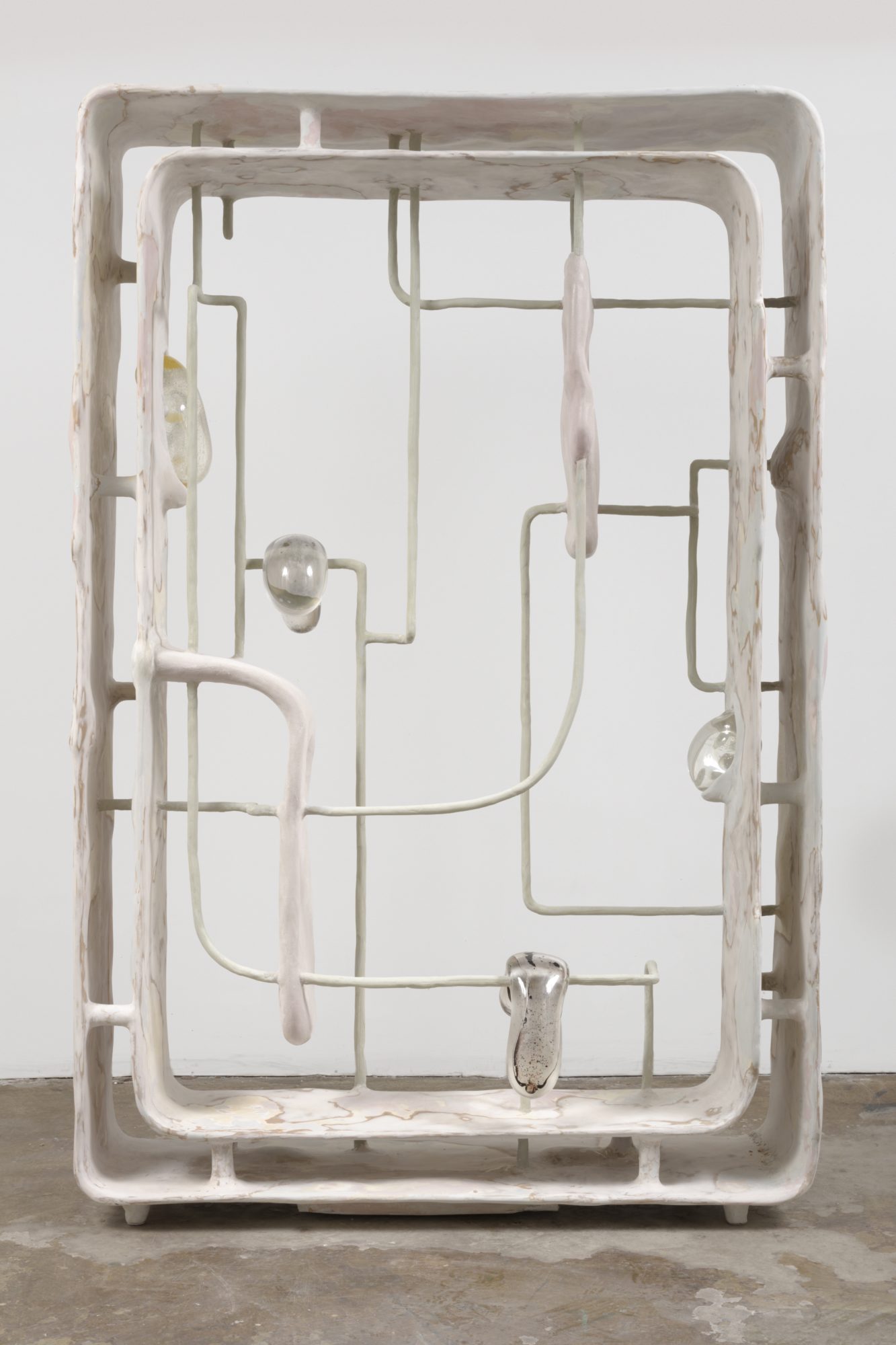

Left to Right: Jes Fan, Form Begets Function, 2020; and Xenophoria, 2020, installation view for the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia [photo: Ken Leanfore; courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong; and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia]

Share:

In the United States there is a long history of positioning the foreign, non-White body as a viral contaminant. Confinement camps were built and exclusionary laws enforced. Government funding continues to enhance border walls, and detention centers remain filled. Covid-19 has only accelerated the rate at which this ideology propagates, with fatal attacks against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders increasing thanks to xenophobic equations of Covid-19 with the “Chinese virus.” This phenomenon isn’t novel. In the 1800s, Chinese migrants were situated as vessels of disease, their living quarters and cultural practices deemed abhorrent by White Americans who then went on to expel, lynch, and massacre America’s Asian inhabitants. Jes Fan considers how the body’s racialized and gendered corporeal signifiers have come to hold so much political and social consequence.

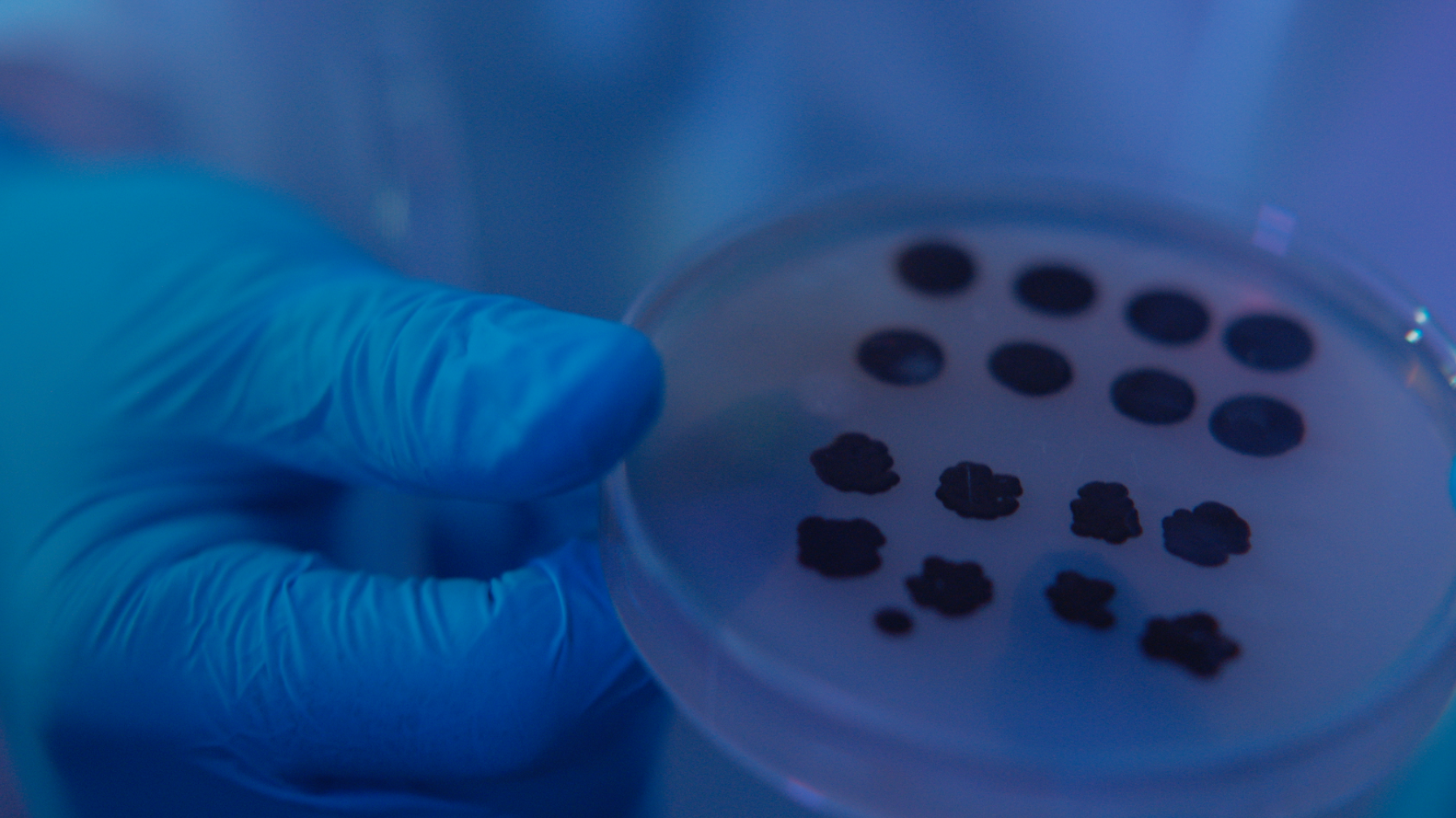

Fan suspends—in intricate lattice structures made of glass, wood, or resin—molecules and microbes that we associate with the ecosystems of contemporary life: melanin, estrogen and testosterone, black mold. Rather than sourcing these elements from familiar entities, Fan isolates their presence in E. coli, fungi, tumors, squid ink sacs, and his mother’s urine, exposing the interlaced networks that trouble any clear distinction between bios and zoē, male and female, native and non-native. By drawing attention to the slippery nature of strict categorical identifications, Fan reveals the violent history of biopolitics embedded within the substances that exist in our everyday and their relative insignificance when uncoupled from conventional associations.

Fan and I met over Zoom on a sunny March day. Our conversation manifested in a fashion similar to the root networks that drive much of Fan’s work: expanding, entwining, overlapping, and, sometimes, leading nowhere.

Jes Fan, Xenophoria (still), 2018-2020, video, HD Color, 07:35 minutes [courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

Sasha Cordingley: Good morning.

Jes Fan: Good, good, good morning. What time zone are you?

SC: I’m just outside of London. Where are you exactly?

JF: I’m in New York City—in Brooklyn. Is the lockdown in the UK quite strict right now?

SC: It has been, but at least we have a lockdown, unlike the United States.

JF: Yeah, the more I live in the United States, I realize every state is its own country. Luckily, New York state has been pretty good. And I lived through SARS. I grew up in Hong Kong during that time. It’s a funny experience seeing how serious Asia’s taking it, especially in Hong Kong’s context. I think it all roots down to the idea of the White body—and the White masculine body—as impenetrable, and [how] it can’t be a contaminant and it cannot be contaminated upon. Like, the White male as a heroic figure that is a completely sealed sausage package—it can’t be penetrated in that way. I think not being able to see yourself as a vector or contaminant is really at the core of the issue—it’s so beyond their racial imagining.

There are so many parallels between racial contaminants and viral contaminants. After the Black Plague in Hong Kong in the [late] 1800s, the British actually [formally] segregated the highest altitude of real estate in Hong Kong—“no Chinese”—as a way to exclude any racial infiltration. Think about Jim Crow law as the segregation of bodies of water—to swim, to drink, and to shower. Those are also hygienic “forms” of segregation.

Jes Fan, Xenophoria (still), 2018-2020, video, HD Color, 07:35 minutes [courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

SC: Are you thinking through these themes in your work?

JF: Yeah, I’ve been thinking about these things for a while now—ever since I’ve been researching the painting by Lam Qua. I stumbled onto them while reading Ari Larissa Heinrich’s book Chinese Surplus. I’m actually working with Ari on a publication through the Andy Warhol Foundation [Arts Writers] Grant. I was thinking about fears of racial contamination when I was doing my residency at Recess in Brooklyn—on creating melanin out of E. coli—and I was adamant about using E. coli as a host rather than using basic tools in biology, or yeast, because that racial fear of contamination, that viral fear, is so innate. And there are so many parallels, I thought it was important in the context of the piece I was working on. So, I started doing this video essay documenting melanin in human bodies, in cephalopod bodies, in fungi, and in these tumors of Lam Qua.

The melanized tumors were included in the film, but I was thinking along the lines of the technologies of creating Chinese-ness. What are the technologies involved in painting, as a technology, at the time? Same with photography, and the kind of erotic nature of them—they’re very seductive in a sense. [Lam Qua is] such a mysterious figure, too. There’s not a lot of documentation on his life, in particular. But he owned his own three-story painting facility. So, he was kind of like the Jeff Koons of Canton at the time. If you see some of his paintings that were commissioned by Peter Parker, you can see sections of [them] where some artisans painted the head, and some painted the body, and some painted the feet, and some painted the background.

Jes Fan, Form Begets Function, 2020, aqua resin, pigment, wood, fiberglass, glass, urine, depo-testosterone, melanin, 50 x 76 x 16 inches [photo: Lance Brewer; courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

SC: Correct me if I’m wrong, but I’ve read that science is a little bit behind when it comes to breaking down the dichotomies, or the binaries, within human nature—especially if we’re thinking about a racialized and gendered body. How are you working within those fields, and how are you challenging them?

JF: I don’t know that that’s absolutely accurate, because [science] is also delivering a lot of groundbreaking information and research regarding that realm. It’s also a lived experience that we can’t force upon other people. The dichotomy between science and art is funny. I got into science because I had a residency at a museum that had a history in craft, the Museum of Arts and Design, and I was thinking a lot about what craft is. I’m not so interested in techniques, but I’m really interested in process, and that’s what drew me into studying glass in undergrad. In a lot of my work, the process of making something actually influences that idea of, or becomes part of, the idea of the piece.

If you think about it, the ultimate [aim] of craft is really material engineering. It’s so similar in those ways. I just started going down that rabbit hole and decided to do a workshop on biological sciences as a way of crafting bodies, and then started working with a couple of other artists who are working along the lines of distilling hormones and body hacking, and that matured into a totally different body of work. A lot of these relationships with material sciences and biological sciences, ultimately, [are] kind of linked at the end.

SC: It’s interesting, the way that craft and engineering have been posited against each other, but actually they’re one and the same.

JF: Yeah, if you think about CRISPR, they go in and they cut certain types of genome, but, you know, the idea of cutting is, as someone who’s not a scientist: “X-Acto knife!” If I upgrade it, we can use surgical knives, and CRISPR uses a chemical way of cutting. But the ideas are very, very similar.

The biology lab I worked with for a while [is] situated in Brooklyn, in this building that’s owned by this guy who’s the funkiest landlord ever. It’s a really rundown building—like a community working space that’s post-apocalyptic. There are welders, podcast people, and then there’s a tier-three biosafety lab. This whole kind of messiness. And that’s also why, in the work, the motif you see is a lot of entangled matrices: the tubing, the entanglement, the root network. A term that I’ve been thinking about is stolonic thinking, [from] Deboleena Roy, who wrote Molecular Feminisms. She introduces this idea of stolonic thinking, stolon being the root network of grass. If you look closely enough, and you go low on the ground, the [stolons] of grass are actually on top of the soil, and they create various webbings. That’s something that I draw inspiration from, that kind of structure, going nowhere but also expanding at the same time.

SC: You used to use the human body to interact with your sculptures in your earlier pieces, but it’s kind of evolved into having sculptures and structures replace it, materials which mimic body parts and their functions. Was this a conscious transition, and what made you move away from the corporeal?

JF: I don’t really see myself as having moved away, because even with the diagram series—they’re smaller, wall-bound sculptures I’ve been making in my studio—they usually come from molds of bodies, but I sand them down to a point where they’re reduced to something that’s so familiar, but you can’t tell which body part it is. I’m not sure if I have exactly left the subject matter of the human body yet. But I’m definitely finding more resonance, back to the idea of webbing, alongside … it, with other kinds of nonanthropocentric points of inspiration. Root networks are something I look into a lot, and fungi, like Anna Tsing’s book The Mushroom at the End of the World.

SC: Are you thinking through these things via the lens of kinship and the Cthulhucene?

Jes Fan, Xenophoria (still), 2018-2020, video, HD Color, 07:35 minutes [courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

JF: Yeah, kinship is something I think a lot about, and how to extend kin beyond blood but also beyond a special connection. I think you can also have kin[ship] with a place. I’m working on a project right now that takes place in Hong Kong—especially with all the dramatic changes that have happened to it in the past few years—with scientist Dr. Yan Wa-tat at the University of Hong Kong. I’m making pearls from these oysters [Pinctada fucata] and cultivating them. He specializes in implanting RFID chips in pearls so that you can use your phone, and tap on the pearl, and the RFID chip will tell you how big the pearl is. I want to transform it—tap the pearl and it’ll send you a URL link to something, like a poem or a video.

The pandemic also really delineated who is your kin, who is part of your home, who was allowed in and not allowed in, not just within the unit of the country but also within the unit of the individual. And that’s something, as an immigrant to the United States, I struggle a lot with. Because, on a personal level, I do have a lot of friends and networks, but who’s family here is a different matter. I’m so lucky to be queer, because I feel like queerness offers a paradigm that’s different than how heterosexual people navigate kinship. There’s been such a long history of queers taking care of each other and having a chosen family. It’s kind of a blessing when your biological family’s inaccessible.

SC: You previously brought up Byung-Chul Han’s concept of beauty and smoothness as being equated to accessibility and consumer culture. How does smoothness play into your work?

JF: I want to bring in smoothness as the idea of seamless interaction, seamless transition, or the smoothness of the digital image right now, from one image, and then you scroll, and then another—this hellscroll of just one image after another. You know how people talk about the Bronze Age, the Industrial Age? I feel like we’re maybe in the Glass Age—what we touch the most is actually glass. Prior to this, how often have you touched glass? When did you go through a day without looking at a screen? Never, ever again, not even when taking a taxi.

SC: Another aspect of it is the fact that we are now so removed from the process of making things.

Jes Fan, Xenophoria (still), 2018-2020, video, HD Color, 07:35 minutes [courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

JF: Yeah. There’s this book called Pig 05049, by Christien Meindertsma, where she traces this one pig, 05049, in the slaughterhouse, and chases and maps up all the individual products that branch from one singular body, including gelatin, or shelves. From medical supplies … from the blood of the pig to tattoo ink: how one single body circulates within the economy of consumption. That’s also a huge inspiration in my work, going back to the idea of webbing, entanglement.

SC: How do you go about sourcing the materials and transforming them?

JF: My family have a long history in manufacturing. Like, my dad started with making toys. And on my mom’s side—my grandfather made a lot of tapestry and doilies to be exported to America. I think the whole idea of how it’s made, what it’s made of, has been really pertinent to me ever since I was a little kid. What is that made of? How can I make it? Those are still guiding questions in my practice. How does it define certain identities? Why do we associate masculinity with testosterone so simultaneously? How does the substance become a signifier for the identity? I don’t particularly have an answer, but I think asking questions without answers are very important in the creative process.

SC: What materials are you working with right now?

JF: These new pieces for the Liverpool Biennial, they’re pretty big—they’re a hundred inches by sixty inches? Inside this kind of tumorous mass is a specific type of mold that I’ve been working with called Phycomyces zygospore. So, there’s three of these structures, and they’re all meant to be low and lying on the ground. This mold looks like human hair when encapsulated in silicone. There’s something really fascinating, as well, about black mold—how we associate it with something so toxic and dangerous, but it’s actually vital in the production of citric acid, which is essentially how we all have access to processed food. But it’s a household contamination we regard as the opposite of preservation. Black mold is actually a major ingredient in penicillin.

Jes Fan, Xenophoria (still), 2018-2020, video, HD Color, 07:35 minutes [courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

Jes Fan, Xenophoria (still), 2018-2020, video, HD Color, 07:35 minutes [courtesy of the artist and Empty Gallery, Hong Kong]

SC: This ties back to the idea of the way that biomolecules and microbes have some political significance—thinking specifically about MSG and the way it has been racialized, despite the fact that it exists naturally in many foods. This speaks to … things that we perceive to be contaminants as being a vital source for things we use on a daily basis and come to rely on.

JF: Totally. Maybe a longer-term research project for me is trying to understand, more thoroughly, how these signifiers become bearers of certain identities. Right now, I’m looking at black mold as a way of navigating that. In the past, I’ve looked into pharmaceutical estrogen and testosterone in those ways.

SC: This ties back to the idea of the way that biomolecules and microbes have some political significance—thinking specifically about MSG and the way it has been racialized, despite the fact that it exists naturally in many foods. This speaks to … things that we perceive to be contaminants as being a vital source for things we use on a daily basis and come to rely on.

JF: Totally. Maybe a longer-term research project for me is trying to understand, more thoroughly, how these signifiers become bearers of certain identities. Right now, I’m looking at black mold as a way of navigating that. In the past, I’ve looked into pharmaceutical estrogen and testosterone in those ways.

All three works for the Liverpool Biennial are part of a series called network: Network (For Survival), Network (For Staying Low to the Ground), and Network (For Dispersal). My scientific collaborator and I actually spent a lot of time and energy [in] trying to cultivate these black molds. They’re really fussy to grow when done intentionally. You have to sustain the right humidity, and you have to time their growth rate at the same time as the glass fabrication. They also require various vitamins in them, because we also have aesthetic concerns, and the culture and the media [have] to be as transparent as possible. We settled on Gelzan, in the end. It’s such an elaborate process, because there wasn’t a lot of scientific literature on how to grow it on a transparent medium, so it was a lot of trial and error. The dangerous thing is actually preventing … contamination from other spores, because spores are like a virus. So, we had to make sure that the spores within the laboratory didn’t contaminate the glass [or] the specific strain of black mold we were working with. Even the air we’re breathing in right now has so many different types of spores.

Jes Fan, Networks (series), 2020 – ongoing, at Lewis’s Building [photo: Rob Battersby; courtesy of the Liverpool Biennial]

SC: It’s interesting that the only thing that can freely move right now is spores, microbes, and molecules.

JF: They’re thriving. I’ve been watching this anime series called The Time I Got Reincarnated as a Slime. I kind of want to make a series of work out of it, because I’m, like, that’s so amazing.

SC: What do you think you would be reincarnated as?

JF: If I do end up being reincarnated into something that I don’t want to be, I hope it’s a short lifetime so I can be reincarnated as something else.

SC: What is the most fascinating thing that you’ve learned through your research and your work?

JF: I often bring back this metaphor: to me, what a successful sculpture yields is [like] the experience when you look at a lemon [and] you feel that sourness in your jaw—that collapse between the visual trigger and the corporeal memory that [follows]. What is it when you see a lemon that triggers your memory of consuming it? That’s something I’m perpetually interested in re-creating in my sculptures. So, I think that’s something. And in doing my research … in working with “infectious” materials—like urine, or blood, or semen—what does that trigger in people?