Jennifer Wen Ma: Cry Joy Park—Gardens of Dark and Light

Jennifer Wen Ma, “Cry Joy Park,” installation view, 2019 [photo: Rick Rhodes; courtesy of the artist and the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston]

Share:

The state of blessedness has been long mythologized as a garden, an enclosure that protects verdure and growth. Not to be confused with the state of nature, where plants grow as they will, but a design, something chosen and created, precious because it can be lost. Jennifer Wen Ma’s Cry Joy Park draws on operatic references to such gardens and paradise lost––in Paradise Interrupted and Peony Pavilion––and regained. Ma’s traveling and evolving installation deliberately directs attention to nested frameworks of semiotic content that might fit into this notion of the ideal state of being, and to the ebbs and flows, the ongoing adjustments that express developing ideas of civilization.

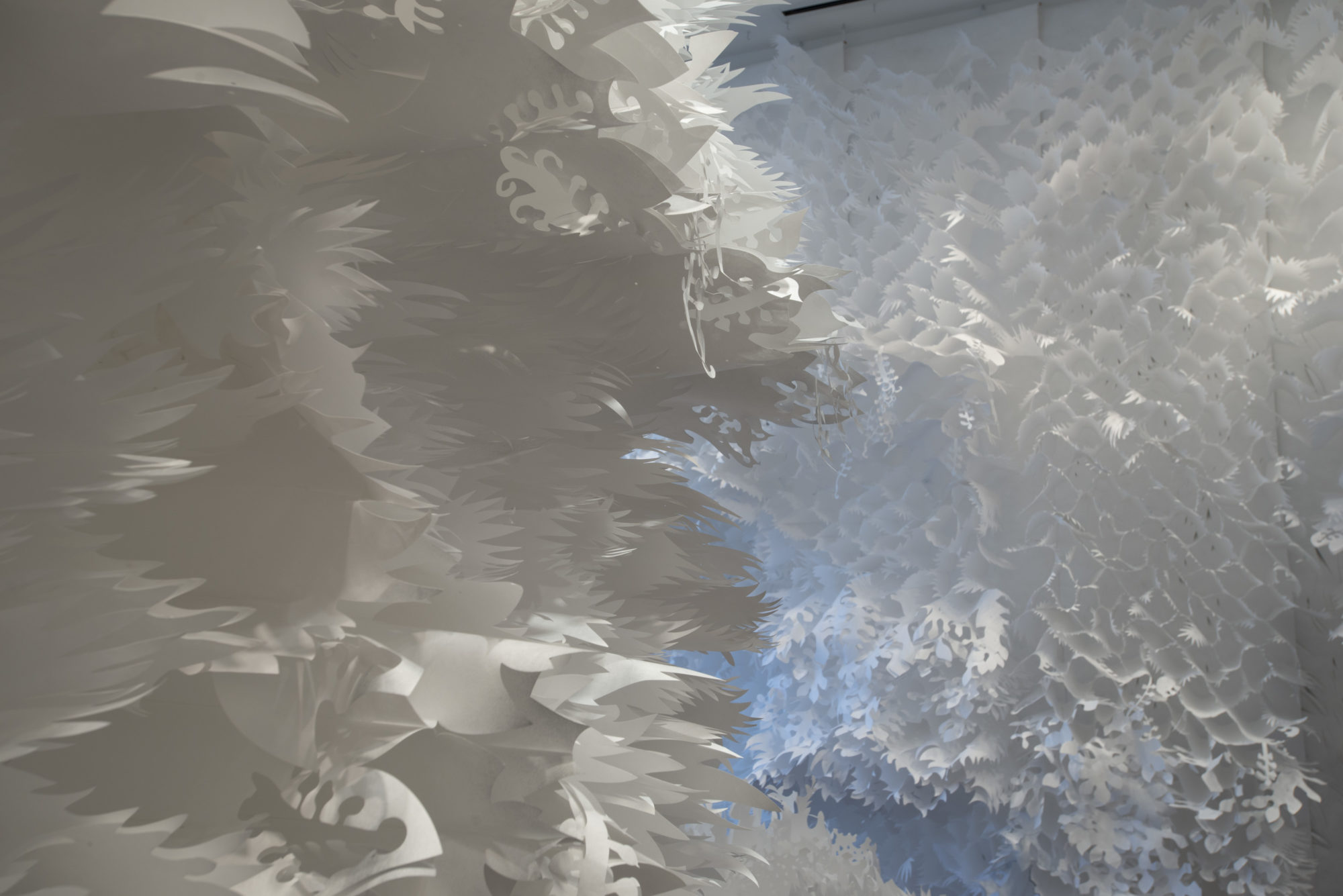

As encountered at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, the installation and associated event series provoke questions about the city itself: who is welcome? who is absent? The top-lit dark garden, through which visitors must pass to enter the bright garden or the dining room, evokes memories of jungles, hanging gardens, even the relief of shaded sidewalks in sun-washed cities like Charleston. Passing through a fringed yoni doorway, one enters the overlit and too-pristine but still compelling bright garden, which in the air-conditioned space almost seems to replicate the mobility of living plants. This room operates as a kind of hypermuseum, leading the eye upward and filled with shadow play, reflective panels, music, and white Tyvek scrolls that hang from the ceiling, beautifully perforated with leaf forms. Two portraits of Charleston and a dining room set for 26 in another room stand in for the question of the Holy City’s holiness.

Jennifer Wen Ma, “Cry Joy Park,” installation view, 2019 [photo: Rick Rhodes; courtesy of the artist and the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston]

Hung back to back in the dark and bright gardens, the portraits of Charleston are rendered minimally in Chinese ink on large Plexiglas panels, surrounded by storms (of climate change? of history?) and backed with silver, so that the image includes the person viewing. In the dark garden the city’s portrait is stylized with an oak tree and a rural house. Looking closer, one can distinguish human figures gathering in the woods, then rising. In the bright garden the city appears as an abstracted urban layout just slightly above the rising waters (Charleston sits only 12 feet above sea level), with one visible church spire. Visitors confidently identified this as St. Michael’s. In the artist talk on May 18, 2019, Ma said that she made the decision to include this detail because Notre Dame burned as she was finishing the painting. Rather than any particular building, the spire signals the idea of the city, its beauty and vulnerability, its capacity to house and to harm. The Laurasian myth of paradise always includes forbidden fruit and tales of fratricide. Sexual references throughout the installation offer resonances of another kind of frequently pursued bliss. Although the gardens themselves appear to be mostly foliage, flowers and distinctly scrotal light fixtures of beaten copper hang over a long table in the adjoining dining room.

Cry Joy Park’s elaborate paper engineering immediately sparks questions about the intersection of art and labor. Ma is quite open about its roots in her other work and about her work process. Having used sewn, honeycombed 3-D panels rather than the usual, flat opera backgrounds employed during her work on Paradise Interrupted at the Spoleto Festival USA in 2014, the artist already knew that Tyvek was good to work with––printable, easy to sew, durable, impervious to the clumsiness of stagehands. Her dress for the artist talk was made from the same material, dyed a different color. She estimates that she spent six weeks calculating, doing the math, making models, and studying pop-up books to determine how best to use her materials. The white and black printed Tyvek sheets arrived and took a week to cut, then another two weeks to hand sew into waffle-folded panels that could be laid flat for packing and shipping. The process of installation is also quite lengthy. The finished product necessarily involves a community. Ma’s work offers strong resistance to the notion of the artist as autonomous genius.

Jennifer Wen Ma, “Cry Joy Park,” installation view, 2019 [photo: Rick Rhodes; courtesy of the artist and the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston]

Behind the unrelieved whiteness of the bright garden a smaller room showcases two colorful painted scrolls of black silk, reminders of a larger semiotic framing: not just the idea of the city but of civilization itself, and the threads that link Charleston to China, one of the most ancient surviving societies. Ma encouraged gallery visitors to consider this kinship as she answered questions in the artist talk. Speaking perfect indirect Charlestonian, she discussed the goals of her project and reflected on how she had hoped to engage the inhabitants of Beijing—where Cry Joy Park’s first iteration was on view October 27–December 15, 2018—to reflect on their social justice issues, particularly ones of class. In the revolution China was promised a classless society, but now that country has an enormous gap between rich and poor. Language about the installation in China characterized the work as an examination of the contradictory values embodied in human civilizations.

Without directly comparing the two societies, Ma teased the 100 or so attendees of her artist talk about wedding china customs. Someone had asked why the chairs (and plates) around the dining table didn’t match. She replied with a reference to the budget, but also pointed out that borrowing the chairs was another way to create communal investment in the installation. Her team had been able to purchase high-quality dishes, however, for very little cost. Sketching out a portrait of the city’s values in a story about the necessity of having this conspicuous-consumption item that is seldom used, then not passed on to the next generation because its members want their own useless collection which loses value and will go to the estate sale or thrift store, Ma never mentioned race.

Jennifer Wen Ma, “Cry Joy Park,” installation view, 2019 [photo: Rick Rhodes; courtesy of the artist and the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston]

Rather, she highlighted partnerships with community activists—in particular Jessica Boylston, whose group Ideas into Action will organize weekly dinners in the gallery to generate dialogue on land use, re-entry after incarceration, and food justice. The first dinner is to focus on children as a group traditionally excluded from the table of community. At the opening several children participated in a ritual by reading abridged verses from Qu Yuan, invoking the four directions and summoning the soul home. Then Dr. Ade Ofunniyin, who earlier in the month had officiated at the reburial of the “Gaillard 36,” led a West African tasting rite for newborns. This event was the only direct reference to a subject much in Charleston-area news during the past few years: finding ways to move beyond a history of the city that honors only half of its creators.

Jennifer Wen Ma, “Cry Joy Park,” installation view, 2019 [photo: Rick Rhodes; courtesy of the artist and the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston]

Hester L. (“Lee”) Furey is a literary historian and poet living in Atlanta. She is the editor of Dictionary of Literary Biography Volume 345: American Radical and Reform Writers, Second Series, and the author of Skeleton Woman Buys the Ticket.