Jamal Cyrus: The End of My Beginning

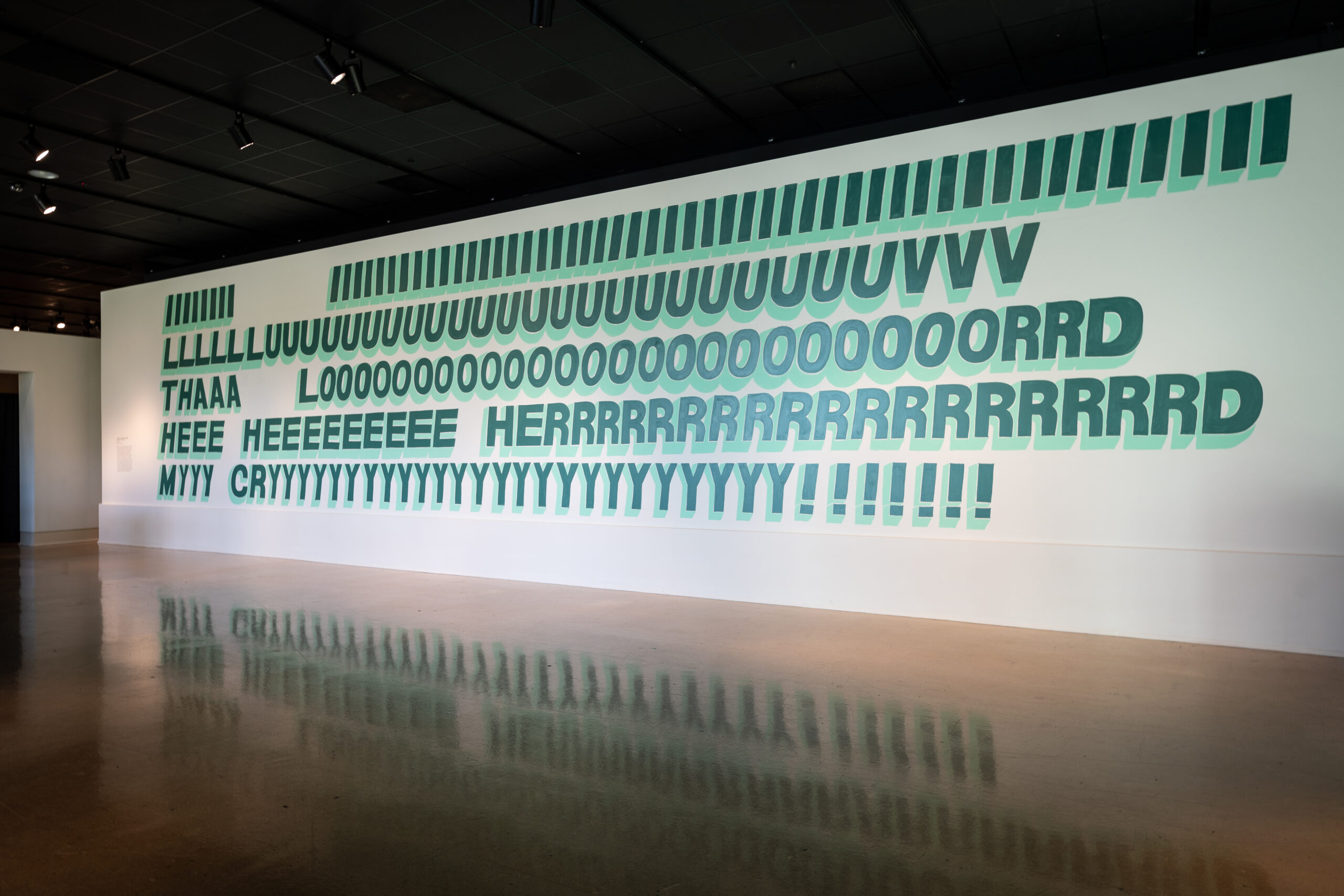

Jamal Cyrus and Walter Stanciell, ILUVTHALORD,HEHERDMYCRY, 2022, latex paint

[courtesy of the artist and Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson]

Share:

Jamal Cyrus’ The End of My Beginning is a survey exhibition that includes more than 40 works made over a nearly 20–year span. The selections show Cyrus’ consistency of thought and the range of his expression through various forms. The show’s title strikes a tone of finality. It sounds as if what we see in this show we might not see again. But because we’re always on the verge of something new, or because no one wants to be in the middle of something, I think this phrasing emphasizes the contrarian nature of Cyrus’ practice. His works always indicate some internal conflict or reveal the contradictions inherent to our understanding of American culture. Cyrus is overdue for such an expansive museum survey. The exhibition originated at the Blaffer Art Museum in Houston before traveling, first, to the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and then to the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson. It successfully offers enough of the artist’s work to see the throughlines of his production.

Jamal Cyrus, The End of My Beginning, installation view, 2022 [ courtesy of the artist and Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson]

Prevailing themes inherent to the exhibition include music, history, Blackness, espionage, consumerism, and the symbolic qualities of such materials as cotton, charcoal, brass, and certain papers. Visual references to militancy and revolution—especially to 1960s Black Panther–era iconography—are common, but their use is not always straightforward. To be clear, until recently, such symbols of counterculture existed in direct opposition to a single, dominant, mainstream social perspective. They did not act merely as one assertion among an ever-expanding register of memes, symbols, or subculture indicators, as occurs in our pluralistic present—and Cyrus banks on this distinction. Throughout Cyrus’ work is a strict attention to color. Predominantly black–and–white compositions, ones featuring shades of blue or high–visibility orange, are punctuated by the metallic surfaces of different brass or steel items. Natural elements, including coral, wood, moss, and hair, round out the textures. These different materials come together—almost like artifacts—and recombine into novel forms of sculpture and drawing.

Elements of design are crucial here, too: They serve as content, just as they simultaneously present formal qualities. His cultural references range from early Jet magazine ads to kente cloth designs. They also include book and album covers, as well as sign painting. In each of these components, the designer’s need to communicate often outweighs creativity. The artist appears to have opted instead for recognizable forms and compositions to convey a variation on a theme. A similar ethos materializes in much of Cyrus’ work, most often employed as a form of critique. Notably, his approach emphasizes both the lasting power of “revolutionary” iconography and its limitations today. To do so, Cyrus plays with the values of icons and symbols. Some referents are obvious, others more obscure; some represent concepts in earnest, others speak to the tropes of their appearance.

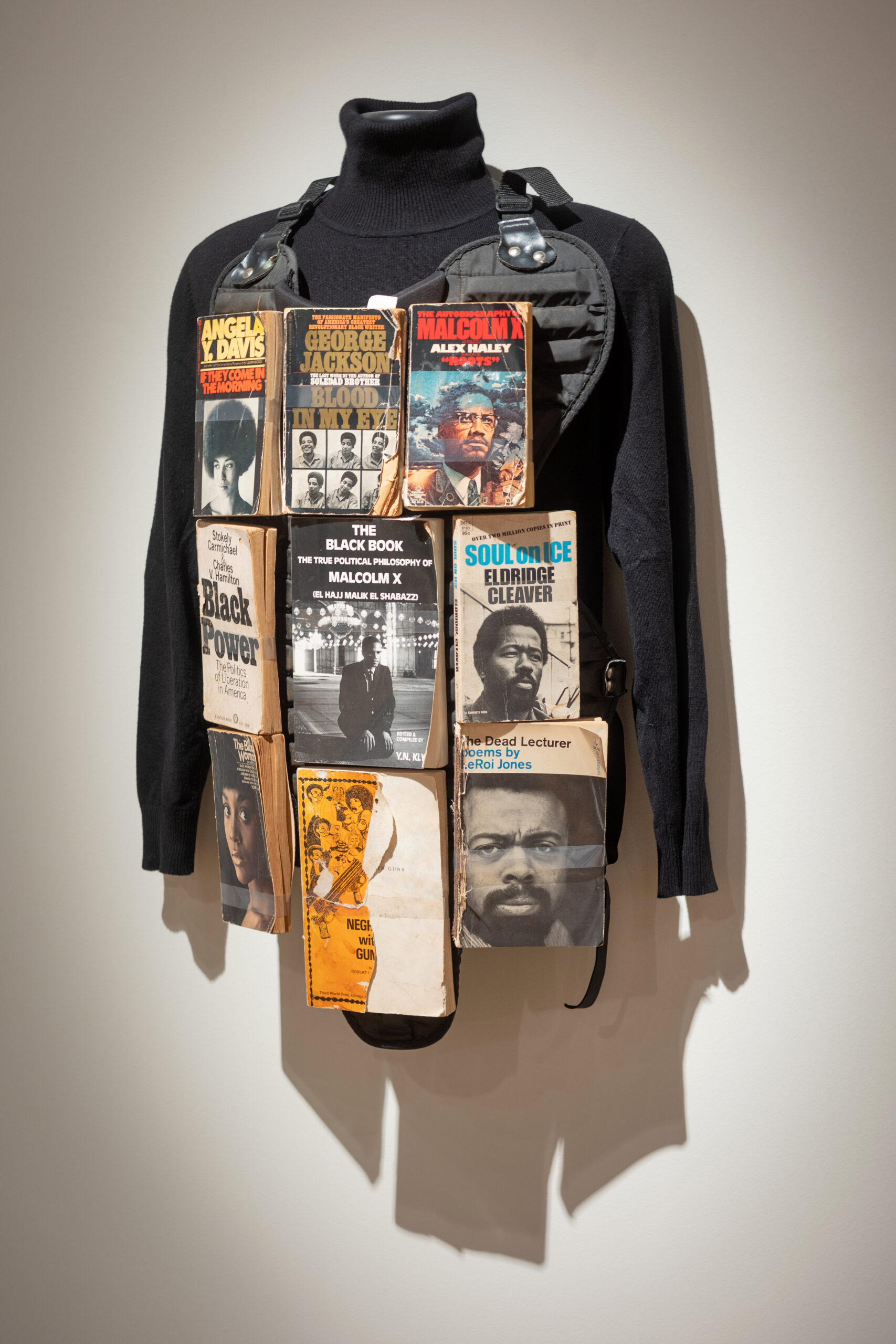

Jamal Cyrus, Africanismus_12469, 2006, found padded vest, paperback books, cotton shirt, 23 x 14 x 4 inches [courtesy of the artist and Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson]

In Africanismus_12469 (2006), a baseball catcher’s chest pad is covered in paperbacks of Black Power literature. The books serve as an added layer of protection. Africanismus_12469 is paired with BPPGG (2016), a black leather jacket, labeled as having pouches of “unspecified contents,” hung behind a thin light-blue curtain. Both objects reference protection and coded adornment. Taken at face value, the black leather and paperback manifestos represent “militancy”—the leather as an outward (and outworn) expression, whereas the tattered book has proved to be far more repellent to the conservative-minded. These elements, and their associations, resonate in different works included in the exhibition. Untitled (Grand Verbalizer What Time Is It?), from 2010, consists of a bass drum, wrapped in padded black leather and surrounded by microphones. These microphones and instruments recall the tools used on the records found throughout the exhibition. Denim—as emblematic of youth and rebellion as it has been a uniform of American labor—is bound to the history of cotton in the United States. In numerous recent works, Cyrus combines strips of denim to reconstruct images of redacted COINTELPRO documents.

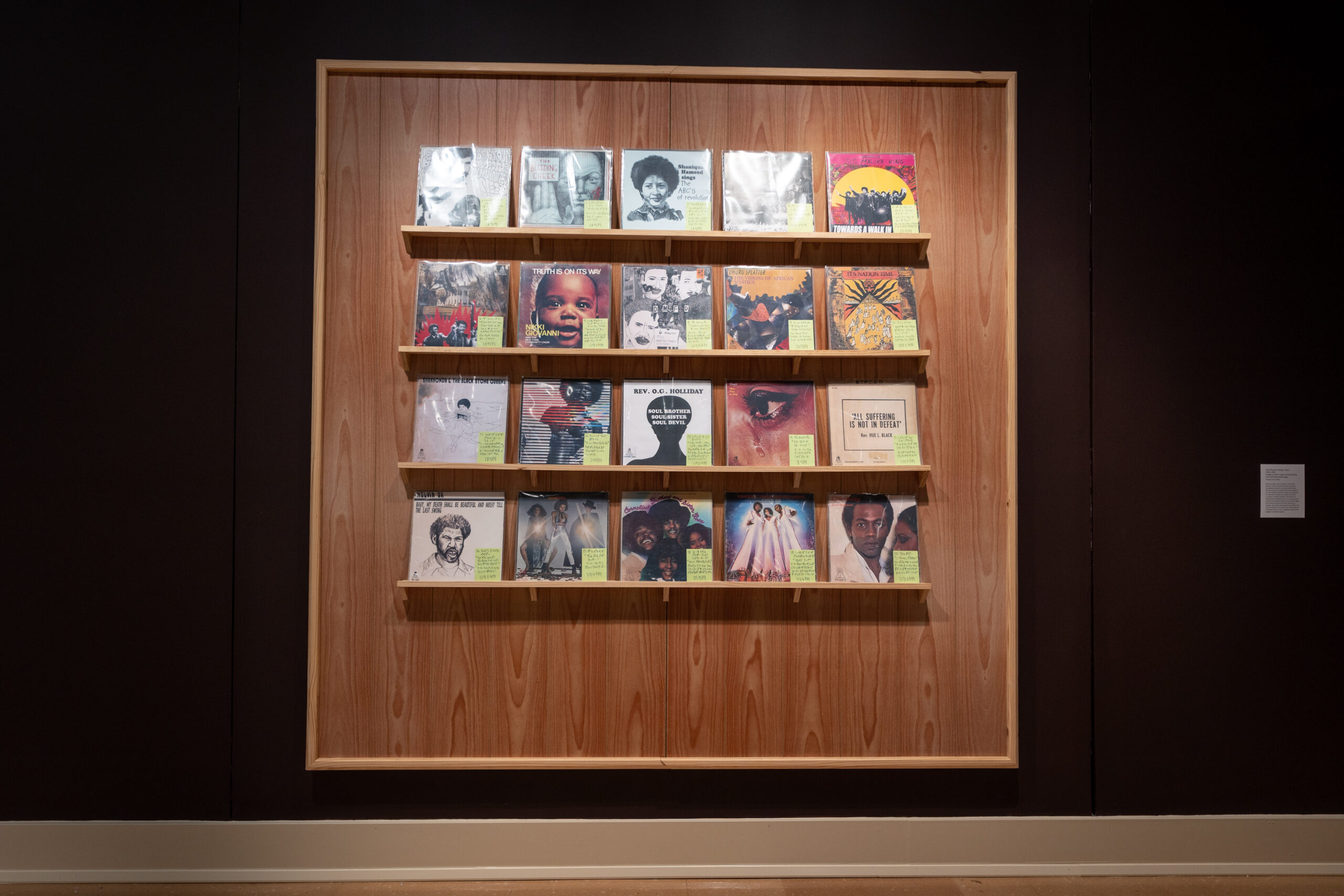

The importance of music here cannot be understated. Music is represented in many ways—overtly, through use of musical instruments, as in his Texas Fried Tenor (2012–) or Conga Bomba (2007–2008, 2021), and categorically in displays of “Pride” records since 2005; an image of musician Isaac Hayes in stained glass, Meshiak III (2021); an oversized reproduction of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme record in Remembrance (For H. Freeman) (2019); and connections to Billie Holiday in a redacted document drawing, Captured Letter From Paris (2019). Surrounded by these items, I couldn’t shake the thought that, in a show of artwork so reliant on recorded music, there should be sound somewhere in the exhibition space. I was rewarded when the sound of someone’s music, playing behind a door, unintentionally filled a small area of the gallery. Regardless of what they were listening to, the encounter was perfect.

Jamal Cyrus, Pride Record findings – Tokyo, 2005-2016, mixed media on album cover, wood paneling, wood shelving, plastic bags, 97 ¼ x 97 ¼ x 2 ⅝ inches [ courtesy of the artist and Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson]

There is no denying the status of music (as a cultural product) in capitalism, because it exists as a product to consume. Cyrus’ “Pride” records and his invented record store façade (Pride Frieze—Jerry White’s Record Shop, Central Avenue, Los Angeles, 2005–17) clearly illustrate this overlap. Therefore, it is the case that American culture is influenced by its commercialization, but the important question is how to understand this culture as a product. How do we rectify the contradiction of our access to—and knowledge of—music, subcultures, and revolutionary/radical ideals through capitalist production and distribution? In other words, how do we understand the music of a favorite musician in light of the fact that our knowledge of that music is the result of it being sold as a product of industrialized entertainment—a system that frequently strives against our own embrace of art itself?

Cyrus recognizes this contradiction—that access to ideas relies on their successful marketing and distribution—and asks us to consider these products together with the remnants, the illegible, the concealed, the edited-out, and the inaccessible parts that went into its production. Through many different means, the artist reminds us to question validity—but more so, the completeness—of cultural artifacts, to separate the facts from legend, and to question the act of that separation. This exhibition presents itself as a looking-back, a conclusion of a beginning, but based on the strength of the works presented here, the thoughtfulness of their presentation, and the accompanying catalogue, I doubt that it’s the end of anything.

Jamal Cyrus, Untitled (Grand Verbalizer What Time Is It?), 2010, Drum, Leather , microphones, mic stands, cables , speaker, 78 x 67 x 45 ½ inches [courtesy of the artist, and Inman Gallery, Houston]

Chad Dawkins is currently a visiting assistant professor of art history and curatorial studies at Spelman College. He has organized many exhibitions, and he is the author of numerous exhibition reviews and catalogue essays, as well as the book The Role of the Artist in Contemporary Art. He is currently writing a history of the activities and impact of the artist-activist group the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition

***

This feature originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Spring 2023 // Artificial Intelligence.