Is there a “post-Black” art?

Kojo Griffin, Untitled (men with molotov cocktails), detail in situ Art Papers 26.06, 2002, mixed media on wood panel, 36 x 42x 3

“Post-black seems to anticipate a movement more than name what currently is going on. It’s a term that wants freedom from these confining identity categories, which rarely get it quite right.” - Laylah Ali

Share:

This essay was originally published in ART PAPERS November/December 2002, Vol 26, issue 6.

As if illustrating a principle of physics, artistic movements seem to spark cycles of action and reaction. Connections to earlier genres define each new development in art, which frequently take “post” as a descriptive prefix. Impressionism begat Post-Impressionism. Modernism gave way to Post-Modernism. A few years ago, a “post-hypnotic show” revealed the influence and evolution of illusionary Op Art. Now, we have a new “post”—Post-Black.

Thelma Golden, deputy director and curator at the Studio Museum of Harlem, used the term “post-Black” to characterize the work of young artists she had selected for last year’s Freestyle exhibition. However, defining this newly-named vein of Black art is difficult. Artists and curators inside and outside the Freestyle orbit have a range of responses to the label “post-Black,” which has created a unique dialogue around this topic.

Golden’s definition of “post-Black” centered largely on art with ideological concerns. In the exhibition catalogue, she described “post-Black” as “a clarifying term that had ideological and chronological dimensions and repercussions,” writing that the new genre was “characterized by artists who were adamant about not being labeled as ‘Black’ artists, though their work was steeped, in fact deeply interested, in redefining complex notions of Blackness.”

“In the beginning,” Golden writes, “there were only a few marked instances of such an outlook, but at the end of the 1990s, it seemed that post-Black had fully entered into the art world’s consciousness. Post-Black was the new Black.”

Intending to tout an emergent generation of pacesetters, Freestyle featured roughly thirty artists from across the US. The show, its title inspired by a popular musical form, was meant to reflect a contemporary creative moment among young Black artists, including Laylah Ali, Rico Gatson, Kojo Griffin, Dave McKenzie, Julie Mehretu, and Kori Newkirk. Multiculturalism informs their work, explains Golden, as does the generation of artists who emerged in the 1980s and 1990s.

Born primarily after the Civil Rights movement and having assimilated the discourse of “Black art,” she says, the artists in Freestyle offer a new perspective on identity, culture and aesthetics. Like their white contemporaries, these artmakers experiment with digital media and sound as well as culture-specific materials like hair pomade and curling papers to explore social, political, sexual, and ethnic issues. From painting and drawing to sculpture, installation and new media, their work reveals the artists’ exposure to both Eastern and Western thought.

Golden notes that more than a few of these emerging artists were inspired by artist Kara Walker and the controversial mythology regarding slavery that she created in the early 1990s with her cutouts of black paper figures in silhouette that subvert stereotypic images of Black culture—work that was (and still is) criticized for its potential to exacerbate and prolong racial prejudice by playing with negative visual symbolism.

Larry Walker, Kara Walker’s father and an active, outspoken artist of an earlier generation, imbues his collages, prints and paintings with his personal, and shared, history as an African American, and finds the expression “post-black” effective to some degree. “On the surface,” he says, “the term is an effort to distance the ideological and methodological concerns of a number of effective African American artists from the tired, misused and inadequate term ‘Black Art.’ In this context, the post-black term has some usefulness.” However, in direct contrast to Golden, Walker feels the term should not “morph into yet another shortsighted term such as ‘the new Black.’”

Both inside and outside the circle drawn by Freestyle, Black artists agree that Golden didn’t invent “post-black.” At least one element of the genre has existed since Black artists began making non-objective art, they believe. “There are so many artists from the past who would fall into this category, artists whose work dealt with aesthetic issues that weren’t necessarily tied to their ethnicity,” says Atlanta-based Kevin Sipp.

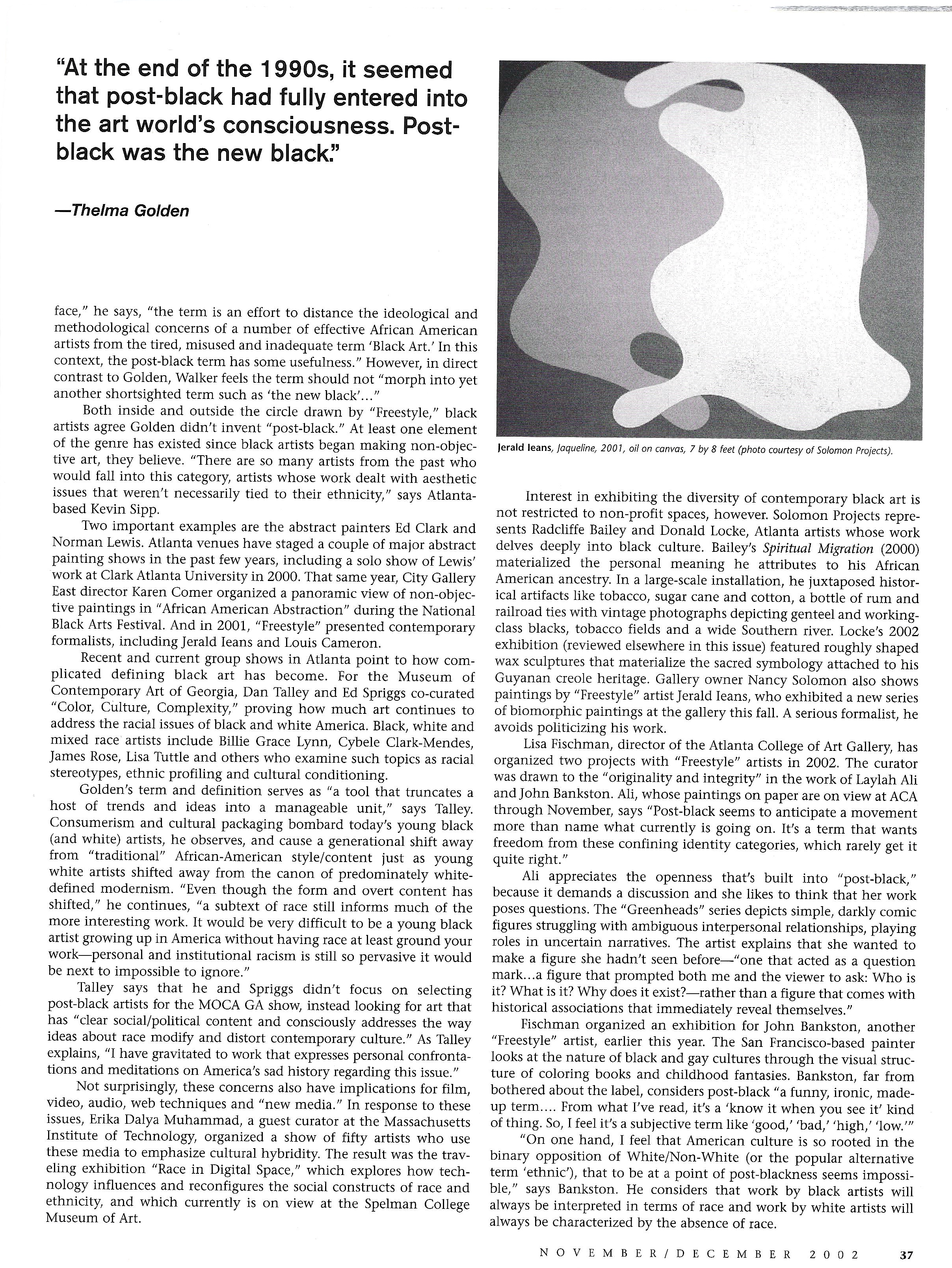

Two important examples are abstract painters Ed Clark and Norman Lewis. Atlanta venues have staged a couple of major abstract painting shows in the past few years, including a solo show of Lewis’ work at Clark Atlanta University in 2000. That same year, City Gallery East director Karen Comer organized a panoramic view of non-objective paintings in “African American Abstraction” during the National Black Arts Festival. And in 2001, Freestyle presented contemporary formalists, including Jerald Ieans and Louis Cameron.

Recent and current group shows in Atlanta point to how complicated defining Black art has become. For the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia, Dan Talley and Ed Spriggs co-curated Color, Culture, Complexity, proving how art continues to address the racial issues of Black and white America. Black, white and mixed race artists include Billie Grace Lynn, Cybele Clark-Mendes, James Rose, Lisa Tuttle and others who examine such topics as racial stereotypes, ethnic profiling, and cultural conditioning.

Golden’s term and definition serves as “a tool that truncates a host of trends and ideas into a manageable unit,” says Talley. Consumerism and cultural packaging bombard today’s young Black (and white) artists, he observes, and cause a generational shift away from “traditional” African-American style/content, just as young white artists shifted away from the canon of predominantly white-defined modernism. “Even though the form and overt content has shifted,” he continues, “a subtext of race still informs much of the more interesting work. It would be very difficult to be a young Black artist growing up in America without having race at least ground your work–personal and institutional racism is still so pervasive it would be next to impossible to ignore.”

Talley says that he and Spriggs didn’t focus on selecting “post-black” artists for the MOCA GA show, instead looking for art that has “clear social/political content and consciously addresses the way ideas about race modify and distort contemporary culture.” As Talley explains, “I have gravitated to work that expresses personal confrontations and meditations on America’s sad history regarding this issue.”

Not surprisingly, these concerns also have implications for film, video, audio, web techniques and new media. In response to these issues, Erika Dalya Muhammad, a guest curator at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, organized a show of fifty artists who use these media to emphasize cultural hybridity. The result was the traveling exhibition Race in Digital Space, which explores how technology influences and reconfigures the social constructs of race and ethnicity, and which currently is on view at the Spelman College Museum of Art.

Interest in exhibiting the diversity of contemporary Black art is not restricted to non-profit spaces, however. Solomon Projects represents Radcliffe Bailey and Donald Locke, Atlanta artists whose work delves deeply into Black culture. Bailey’s Spiritual Migration (2000) materialized the personal meaning he attributes to his African American ancestry. In a large-scale installation, he juxtaposed historical artifacts such as tobacco, sugar cane and cotton, a bottle of rum, and railroad ties with vintage photographs depicting genteel and working–class Black people, tobacco fields and a wide Southern river. Locke’s 2002 exhibition (reviewed elsewhere in this issue) featured roughly shaped wax sculptures that materialize the sacred symbology attached to his Guyanan creole heritage. Gallery owner Nancy Solomon also shows paintings by Freestyle artist Jerald Ieans, who exhibited a new series of biomorphic paintings at the gallery this fall. A serious formalist, he avoids politicizing his work.

Lisa Fischman, director of the Atlanta College of Art Gallery, has organized two projects with Freestyle artists in 2002. The curator was drawn to the “originality and integrity” in the work of Laylah Ali and John Bankston. Ali, whose paintings on paper are on view at ACA through November, says “Post-Black seems to anticipate a movement more than name what currently is going on. It’s a term that wants freedom from these confining identity categories, which rarely get it quite right.”

Ali appreciates the openness that’s built into “post-black,” because it demands a discussion and she likes to think that her work poses questions. The “Greenheads” series depicts simple, darkly comic figures struggling with ambiguous interpersonal relationships, playing roles in uncertain narratives. The artist explains that she wanted to make a figure she hadn’t seen before–”one that acted as a question mark … a figure that prompted both me and the viewer to ask, Who is it? What is it? Why does it exist?—rather than a figure that comes with historical associations that immediately reveal themselves.”

Fischman organized an exhibition for John Bankston, another Freestyle artist, earlier this year. The San Francisco-based painter looks at the nature of Black and gay cultures through the visual structure of coloring books and childhood fantasies. Bankston, far from bothered about the label, considers “post-black” a “funny, ironic, made up term …. From what I’ve read, it’s a ‘know it when you see it’ kind of thing. So, I feel it’s a subjective term like ‘good,’ ‘bad,’ ‘high,’ ‘low.’”

“On one hand, I feel that American culture is so rooted in the binary opposition of white/Non-white (or the popular alternative term “ethnic’), that to be at a point of post-blackness seems impossible,” says Bankston. He considers that work by Black artists will always be interpreted in terms of race and work by white artists will always be characterized by the absence of race.

On the other hand, Bankston views this new reading of race in the work of Black artists as an artistic opportunity. “If issues of race are always present,” he reflects, “then that gives me something to play with in terms of content. I try to complicate that reading by layering it with so many things—issues of gender, high/low culture, painterliness, color/absence of color, drawing/painting.”

Atlanta artist Kojo Griffin, a painter included in the 2000 Whitney Biennial, and later in Freestyle, thinks differently: “I might agree that it was necessary to label what can only loosely be called a ‘generation’ of younger artists to create context for us and to strengthen the historical presence of the previous ‘generation’ of artists by making the younger black artists ‘post-them.’” However, he says, “I do find the use of the term post-black to be somewhat problematic because the word ‘Black’ has so many connotations within society, as well as in the microcosm of the art world. As a person who is very proud of being Black, or of African heritage, I would be reluctant to ever describe myself as post-Black in any sense.”

Griffin’s paintings represent the pathos of disease in relationships. Patterns of dominance and submission are depicted in the visual dynamic of his characters—anthropomorphic animals and doll people who wear clothes and have human hands. It is ironic to classify this content as “post-Black,” he says, when his work takes its form “because of, not in spite of, my cultural heritage. My work reflects both a total realization of what it means to be Black in modern society, as well as an overwhelming desire to push the boundaries of what it means to be a ‘Black artist.’”

Based on his recent curatorial project, it might seem that racial issues grip Atlanta-based artist Charles Nelson who, with Kevin Sipp, co-organized Strange Fruit, an interracial show at Eyedrum Gallery, in which artists responded to the history of lynching in the South, particularly as displayed in the Without Sanctuary exhibition of lynching photographs at the Martin Luther King Center. But race is not the root of his work, he explains: “The kinds of identity issues I deal with are more issues of personal identification-how people identify themselves, how they present themselves to the public, how public perception can be shifted, and how art can play a role in that process.”

According to Nelson, the term “post-Black” is valid, but misguided. “The truth of the matter is that all of American culture, especially today, is rooted in Blackness… African American artists have been trying to be ‘post-Black’ since the 1800s. It is the dilemma of wanting to be considered for the quality of the work and not just the color of your skin…So now,” he says, “we have a group of artists who are being considered because of their race but also because their work does not deal with race. In many ways this is a positive step; what you have is the freedom of expression to present work in broader terms than the tenets set by the 1960s Black art movement.”

Sipp, an Atlanta-based sculptor and painter, also questions Golden’s definition of post-Black art. “It’s an issue that’s been in debate since Africans were brought to the Americas, in my opinion. It’s about assimilation and belonging,” says Sipp, who thinks that not many artists today would choose to be defined as either Black or post-Black.

“Artists may work with race and ethnicity at different times in their careers,” he observes. “I don’t think you can just lump everyone together.” Asked how his own art connects, intersects or opposes art that’s been labeled post-Black, he responds: “That depends on the piece. The ‘Dub Human’ series I made was about my love of reggae music. What I found interesting was that multicultural music labeled African, in fact, had Chinese, Greek and European influences.” Exhibited at Atlanta’s Kubatana Moderne gallery, his works about DJ culture, Shamanism, and ritual traditions draw from worldwide phenomena; their source is not strictly Black.

When Nelson interprets the nomenclature for this new strand of Black art, he nods to Sipp’s acknowledgement of global influences in his work: “I think that the term post-Black is meant to signify a move toward the larger issue of the humanity of African Americans. When a Black figure can stand in as a universal symbol of humanity instead of a loaded symbol of political idealism, then that goal will have been accomplished,” he says.

For Savannah-based Laurie Jackson, whose bleach print abstractions appeared in the inaugural Georgia Triennial exhibition earlier this year, and who will show at Atlanta’s Sandler Hudson Gallery in 2003, the Freestyle show and the surge of interest in the term ‘post- Black’ speak of a new era: “Black, for me, meant existing within an American idea of Blackness. Yet when I began to move outside my circle into a more multiracial, multi-ethnic community, I began to realize that my identity as Black was unique to me.”

Jackson’s background is a mix of what she describes as “African, Anglo European, and Native American.” Her skin color, personal preferences, speech patterns and Philadelphia accent, she says, all inform her art’s examination of common issues across humanity, and “not all codified by a Black experience. I like the idea that my work can be read in a variety of ways. I refer to memory, nostalgia and loss, as well as to a desire to reach to the future.”

On the other hand, the fact that young artists seem to be abandoning cultural specificity in their work disturbs Sipp. He cites a recent ARTnews article that featured ten artists to watch, in which a female Cuban artist and a Chicano artist both described how they had to let go of their ethnicities to do their real work. “Somehow, these artists figured that in order to be acceptable they had to clean their roots, shake off the dirt,” Sipp concludes.

Clearly, the post-Black discourse will be ongoing and intense. However, regardless of their ideological stance or the form or content of their artmaking, many young Black artists hope to ultimately be integrated into the broader canon of Western art history. No one wants to be “just a sidebar of special interest studies,” remarks Nelson.

In the end, the idea of post-Black art seems to effectively describe a new socio-political order that goes beyond the art world. What appears on the outside to be a significant and somewhat surprising burst of really “different” Black art is more a matter of exposure, and results as much from the Civil Rights movement as it does from our globalized and hyper-mediated environment. Years of protests and hard-won legal battles in the social, political and economic arenas, along with decades of Black-centered art, have freed the latest generation of artmakers to say whatever they want with their work. Just as Post-Modernism builds on Modernism, ‘post-Black’ relies on a rich history of intensely ‘Black’ art.

Fischman further elucidates: “The Freestyle exhibition highlighted some really great artists and brought forceful, direct attention to what you might call the distinctive spirit of this younger artistic generation-not a unifying ethos, but a different position, a less direct approach, a more complicating intentionality with regard to the integers of identity considered most crucial by earlier generations. It is a generational luxury and a sign of social change that artists don’t need to make work that overtly states ‘I am a Black woman’ or ‘I am a gay man’—hear me roar. They roar in subterfuge.”

Meanwhile, for a Freestyle insider like Ali, the major effect of the post-Black buzz is simply that “I am now asked what I think ‘post- Black’ means—a question that was never put to me before. The term itself has been one of the viable legacies of the show,” she says.

Increased visibility was a tangible result of being included, admits Griffin. “Being in the Whitney Biennial and Freestyle—along with all the publicity surrounding the shows—becomes part of a cumulative effect that hopefully builds my career.” Even so, he continues, “If I don’t constantly maintain a presence in the art world, then my appearance in these past shows, no matter how prestigious, will not really matter to anyone.”

So post-Black art can’t really be defined as a reaction to ‘Black’ art. The label doesn’t describe a specific emerging conceptual movement or formal approach. Nor does it deny the Blackness of the artists or anticipate their success. Instead, like the title of the show that spawned the notion (and sparked this discussion), post-Black is about improvisation. Emerging Black artists, like artists of any other contemporary ethnic or cultural group, are challenged to evolve-to learn from the past, to explore their stylistic options, to investigate new dimensions of thought, to expose the infinite nuances in today’s culture and to invent fresh idioms in a visual language that defies any prescriptions on what art can be or where it can come from.