Leah Clements—INSOMNIA

Leah Clements, INSOMNIA, installation view, 2022 [photo: Rosie Taylor; courtesy of the artist and South Kiosk, London]

Share:

Leah Clements’ first exhibition of photography, INSOMNIA, comprises a series of grainy photographs and an audio description, which situate the viewer in a zone of affect and conjure the psychological effects of insomnia-related sleep phenomena. Upon entering the inconspicuous industrial space, I am drawn toward the glow of two opposing light boxes, veiled by linen curtains. The room housing these items has the aura of a therapeutic space: deep teal carpet, white walls, partitions, quiet. Except for a voice, low and steady, guiding me forward.

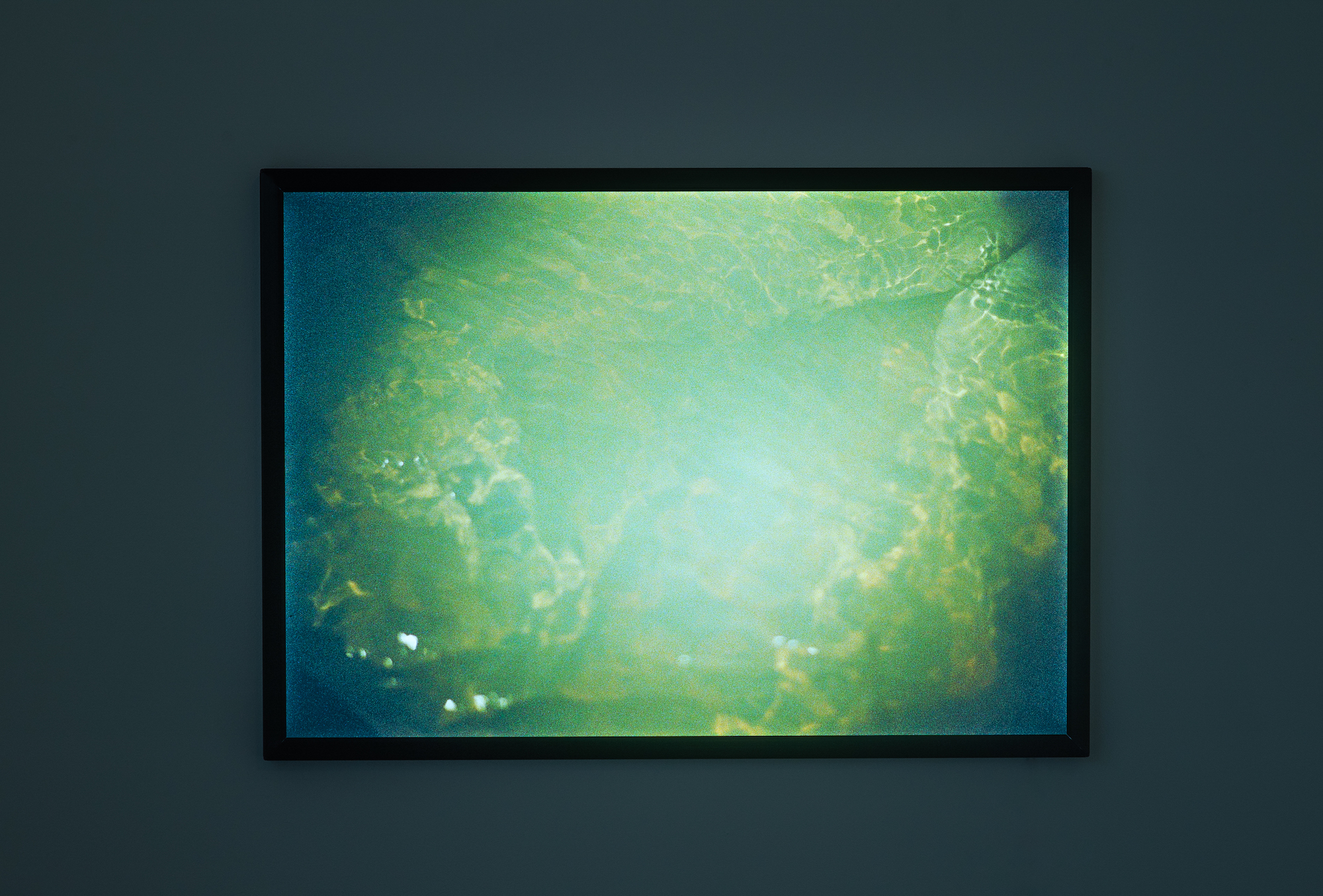

The light boxes—Subsolar (2022) and A Minute, Or Millenia (2022)—illuminate two photographs taken from within a body of water. Ecstatic greens and yellows effervesce into the dim corners of the frame. As I look from one to the other, and back again, they appear to have changed. Looking closer, I try to memorize their abstract folds of light, which, as the titles allude, seem to waver between the intimate and the cosmic. As an entry point to the exhibition, these works mark a realm suspended between surface and depth, sleep and wakefulness.

Leah Clements, Subsolar, 2022, Acrylic lightbox, metal frame, 24 x 34 inches [photo: Rosie Taylor; courtesy of the artist and South Kiosk, London]

The following sequence of photographs is set in vacant and clinical interiors. The compositions focus on fragments and thresholds: a room with an open doorway, a strange light emanating from beyond the frame, a reflection, the suggestion of a person. The South Kiosk gallery itself is made uncanny, echoing the rooms in the photographs with its layout and minimal aesthetic, absorbing us into their visual language. The granular texture of the images furthers this sense of contamination between the exhibition space and the rooms pictured. As I lean in, specks of light become visible and begin to throb, simultaneously evoking form and its disintegration.

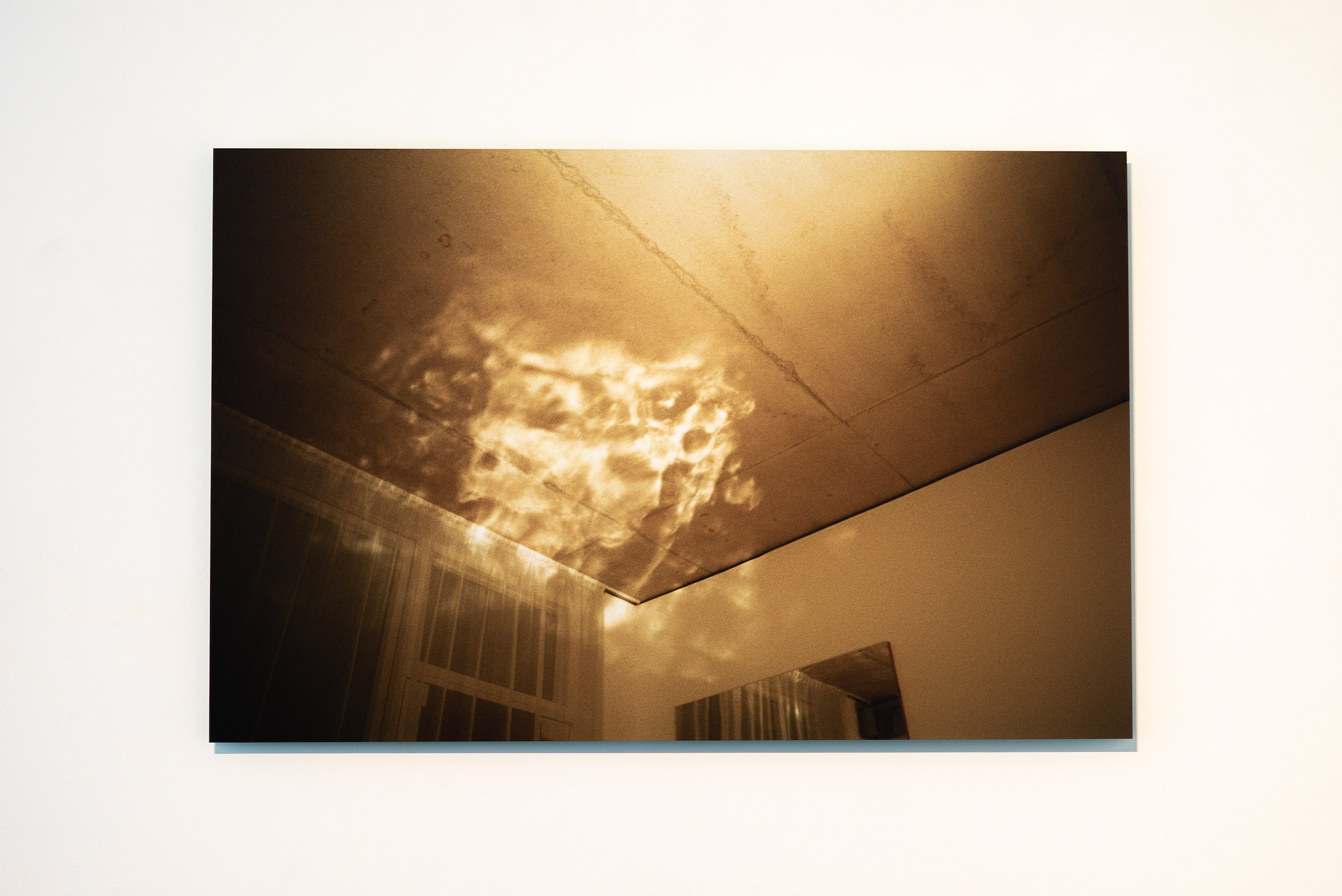

In I Tasted It Before I Felt It (2022), a specter of light is projected from a pool below. The light gathers like white flames in the upper corner of a room, dancing between surfaces—so alien that it seems a double exposure. In the lower right portion of the image is the edge of a mirror which faces the light source and the scene that accumulates before it. Although we know the scene is captured by the mirror, it is beyond the viewer’s grasp. Distracted by a promiscuous light, we must take up the position of disoriented voyeur.

Leah Clements, INSOMNIA, installation view, 2022 [photo: Rosie Taylor; courtesy of the artist and South Kiosk, London]

In each of these photographs, something is happening beyond the frame. The works capture a moment just before we might bear witness. Rather than soliciting frustration however, Clements asks us to surrender to anticipation; to enter a time zone of potentiality where the all-seeing, knowing gaze is halted so that alternative ways of seeing can be practiced. This evocation of a state of unknowing recalls the abject as described in Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror. The abject is the liminal space of sensation that precedes our acquisition of language, as well as the distinction between subject and object, self and other. The abject elicits fear because it is where these dichotomies touch, threatening contamination and therefore the stability of the subject. At the same time, the abject wields a seductive force, drawing us to the ecstasy of pure sensation. The opacity of these photographs undermines our ability to fully know what we are looking at, and in this realm of uncertainty we are liberated from the ideology that equates sight with knowledge. What is invoked, instead, is our desire to know, suspended here in perpetual longing.

Playing at regular intervals in the gallery, a recorded audio description offers loose and poetic interpretations of the works, their relation to each other, and our bodies in the space. The effect is meditative, inviting reflection and an attunement to our environment, and unsettling, implicating the viewer with knowing provocations, speaking to us in present tense, asking “Should we be here?” This articulation of our presence feels participatory. Subverting the viewers’ assumed position as an unobserved onlooker, the voice threatens, “We will be seen.”

Leah Clements, I Tasted It Before I Felt It, 2022, Dibond print, vinyl, 39 x 26 inches [photo: Rosie Taylor; courtesy of the artist and South Kiosk, London]

The audio description’s words gesture beyond the confines of the photographs themselves and expand the affective environment of the exhibition: “Outside our immediate view, darkness encroaches at the edges. Who knows how far that darkness stretches.” As in the rooms beyond the frame of the image, something is always happening elsewhere. Although we might not be able to know it, there is liberatory potential in understanding ourselves as co-existent with that which we cannot capture. Once the voice recedes, I stand in its wake, disoriented by something felt, now vanished. Like the moment immediately after waking from a vivid dream before realities settle on either side of the coin.

Leah Clements, I Stayed Away So Long, 2022, Dibond print, vinyl, 26 x 39 inches [photo: Rosie Taylor; courtesy of the artist and South Kiosk, London]

Providing access to the exhibition for blind and partially sighted people, this audio description acts as a way in for all audiences. Excitingly, here, through this interpretive sonic contribution, the visual aid becomes an affective feature rather than simply a functional element. It affects pace, the order of encounter, and the awareness of oneself in the environment, embedding us within it. It asks us to pay attention, to be indulgent with our time, and in so doing, to allow details and sensations to emerge.

In Don’t Breathe (2022), a room is shown shrouded in darkness. A figure stands at the center of the photograph, framed by a series of open doorways. The figure holds a lamp, which shines an orange beam of light toward us. Another source of light beckons the figure to a place beyond our view. Here, the audio description narrates: “We can’t distinguish their face, but we know they’re about to look at us …. Our presence is known.” Each time I return to this photograph, my interpretation of the figure’s movement changes. Sometimes they cautiously tilt toward me, and at others they are transfixed by the light on the floor. The dim, grainy quality of the photograph makes sight unreliable. It is this opacity, and the call to slow down and return, that allows for shifting experiences of the work. Within this ostensibly static medium, a sense of movement is, nevertheless, generated. At the end of the audio description, we are invited to trespass the temporary wall of the installation to encounter a small final photograph. The lip of a bathtub, the suggestion of a body, and a web of light sprawling across the frame.

Leah Clements, INSOMNIA, installation view, 2022 [photo: Rosie Taylor; courtesy of the artist and South Kiosk, London]

In the context of the past three years of the pandemic, the exhibition speaks to an all-too-familiar alienation and longing. But even more, it gestures to the liberatory potential of alternative engagements with time, space, and the act of looking. What happens when we slow down? When our interpretation shifts on each inspection? When the image evades stasis? With a renewed consciousness of the fallibility of the visual, perhaps more holistic, and embodied ways of knowing can emerge.

Kit Edwards (she/they) is a writer and curator working between London and Cardiff. Her work is invested in queer and crip theory, embodied knowledges, and time-based practices. In 2021 she completed the MA in Contemporary Art Theory at Goldsmiths, University of London, graduating with Distinction. She has previously worked as Assistant Curator at Artes Mundi, and at Metroland Cultures, delivering the Brent Biennial 2022: In the House of My Love. She is currently Studio Manager for Clémentine Bedos. @kitedwards_