Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), installation view, 2021 [photo: Ruben Hamelink; courtesy of the artist, and Framer Framed, Amsterdam]

Indicting the Poisonous Imaginary—Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal

Share:

Indian academic, writer, lawyer, and activist Radha D’Souza says her relationship with the Dutch artist Jonas Staal is rooted in solidarity. They met in 2015 at the Network for an Alternative Quest conference. Then, in 2016, Staal invited D’Souza to participate in New World Summit: Stateless Democracy at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, in Utrecht. The assembly’s name referenced the Kurdish revolutionary movement’s 2012 declaration of Rojava’s autonomy in northern Syria as an independent stateless democracy. This gathering was the sixth staged by New World Summit, a political and artistic organization, founded by Staal as an alternative parliament for political organizations that have been rendered stateless or excluded from democratic processes. D’Souza then participated in New World Embassy: Rojava, a temporary embassy constructed in Oslo City Hall and developed in collaboration with the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava, for whom Staal also worked to design and build an outdoor parliament inaugurated in 2018 in Rojava.

In 2021 D’Souza and Staal came together to stage the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC) at Framer Framed in Amsterdam. Described as “a more-than-human tribunal to prosecute intergenerational climate crimes” committed by Unilever, ING, Airbus, and the Dutch state, the court drew from D’Souza’s book What’s Wrong With Rights? Social Movements, Law and Liberal Imaginations. It proposed a rerouting of rights discourse away from a proprietary culture shaped by the colonial era and subsequent global imperialism, which centered the human within a mercantile culture and denied relations among living things. Between October 28 and 31, 2021, evidence was presented by collectives and individuals engaged in the struggle against climate injustice, among them representatives of Kenya Land Alliance, Pueblos Indígenas Amazónicos Unidos en Defensa de sus Territorios, Vettiver Collective, and Synergie Nationale des Paysans et Riverains du Cameroun.

In this conversation, D’Souza and Staal introduce the project’s critique of the legal system and consider what it means to work from within to find a way out.

Stephanie Bailey: How did your collaboration on the CICC come about?

Radha D’Souza: Because Jonas looks at reconceptualizing society’s embedded institutions, I sent him my book What’s Wrong With Rights?, which outlines the link between the human rights agenda, post-war imperialism, and transnational monopoly capitalism. Jonas told me when he read it [that] he started drawing pictures on the pages, which he showed me.

Jonas Staal: Thinking from a critique of the legal system and the inheritance of peoples’ tribunals—many of which Radha has been involved in—I tried to read Radha’s book as a morphology, considering how her conceptual propositions could translate into alternative organizational forms. Radha speaks about land and nature not as an externality but as relation—something that profoundly challenges how the contemporary rights regime currently organizes and maintains social relations, and demonstrates how an understanding of interdependency could be its substitute.

Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes, Study, 2019, ink on the pages of Radha D’Souza’s What’s Wrong With Rights? [courtesy of the artist]

RD: As Jonas said, I have been involved in many peoples’ tribunals. And when we thought about how to perform this idea, we wanted something proactive. As activists, we are committed to the idea that the role of art is to expand people’s imaginaries, and that is why we took the idea to this form: a tribunal that put the state and corporations on trial. If you look at the whole [of the] legal architecture today, you cannot put states or corporations on trial. That statement relates to legal personhood of corporations and states, and could be clarified as follows:

Legal personhood bestowed on states and corporations endows them with rights as if they were natural persons—for example, corporations have rights to free speech, constitutional rights, and such, and states have rights to contract, [are] required to repay debts, etc.

There is one obligation that natural persons have that corporate persons don’t, and that is criminal liability. For example, in the Bhopal gas leak case the legal arguments centered [on] whether the CEO of Union Carbide could be criminally liable for the actions of Union Carbide. If Union Carbide is a legal person, entitled to all other rights that natural persons have, can we also hold the legal person—i.e., Union Carbide, in this example—criminally liable in its capacity as legal person? If corporations and states are legal persons, just like natural persons, and if I can be put on trial for crimes, can we do the same with legal persons as legal persons? Here the premise of legal personality unravels.

JS: By putting corporations and states on trial, the CICC follows Radha’s work that essentially puts the law and its origins on trial. The legal framework that Radha wrote for the CICC, The Intergenerational Climate Crimes Act, contours the arena so we can trace the roots of the law and the concept of rights to the proprietarization of relationships—the turning of rights into an individual form of property or ownership—which disrupts an awareness of [the] inherent interdependency of our struggles.

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), installation view, 2021 [photo: Ruben Hamelink; courtesy of the artist, and Framer Framed, Amsterdam]

RD: This is something the law always does. It takes certain principles and decontextualizes them completely. So when we talk about law, we never talk about how those laws came about. But when you deal with law in terms of its embeddedness within society, and its historical and sociological processes, it becomes something else altogether.

JS: Putting the law on trial was the foundation that allowed us to appropriate statecraft tactics and turn them back on their source. As with deterrent strikes—when humanitarian law is manipulated to undermine state sovereignty—we do something similar by recognizing that, while the full extent of ecocidal crimes exist in the future, the future has no jurisdiction. So, within our legal framework, we engage in a deterrent strike against these ecocidal actions and their future ramifications in the present. It’s a way of retooling and not reinforcing statecraft from a fundamentally different perspective that acknowledges the relations between living worlds—past, present, and future.

RD: We drafted an alternate statute in very legal language to demonstrate that it was possible to envision another way. We used the same legal language, but with a completely different understanding of the world, which in itself becomes a tool.

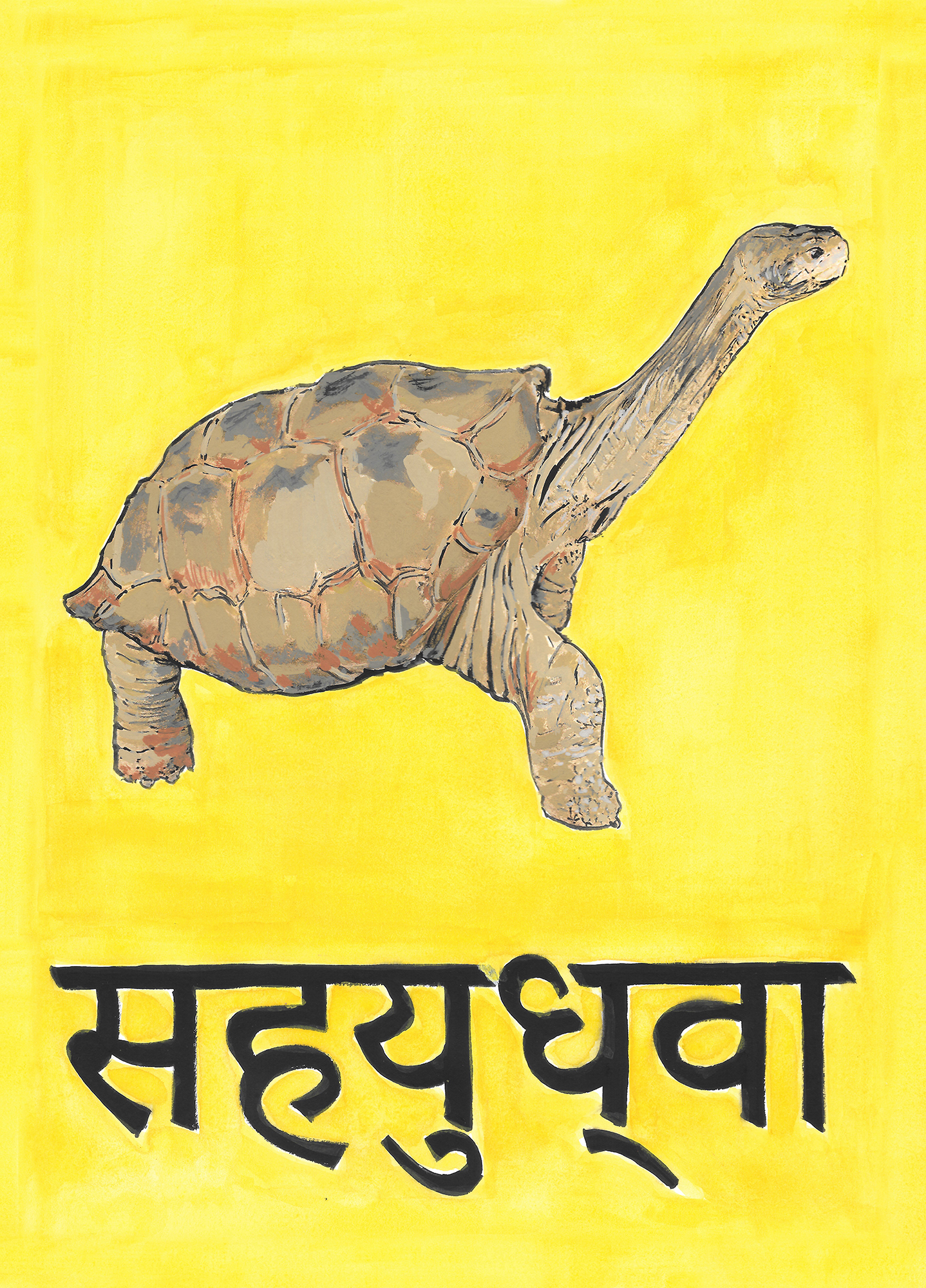

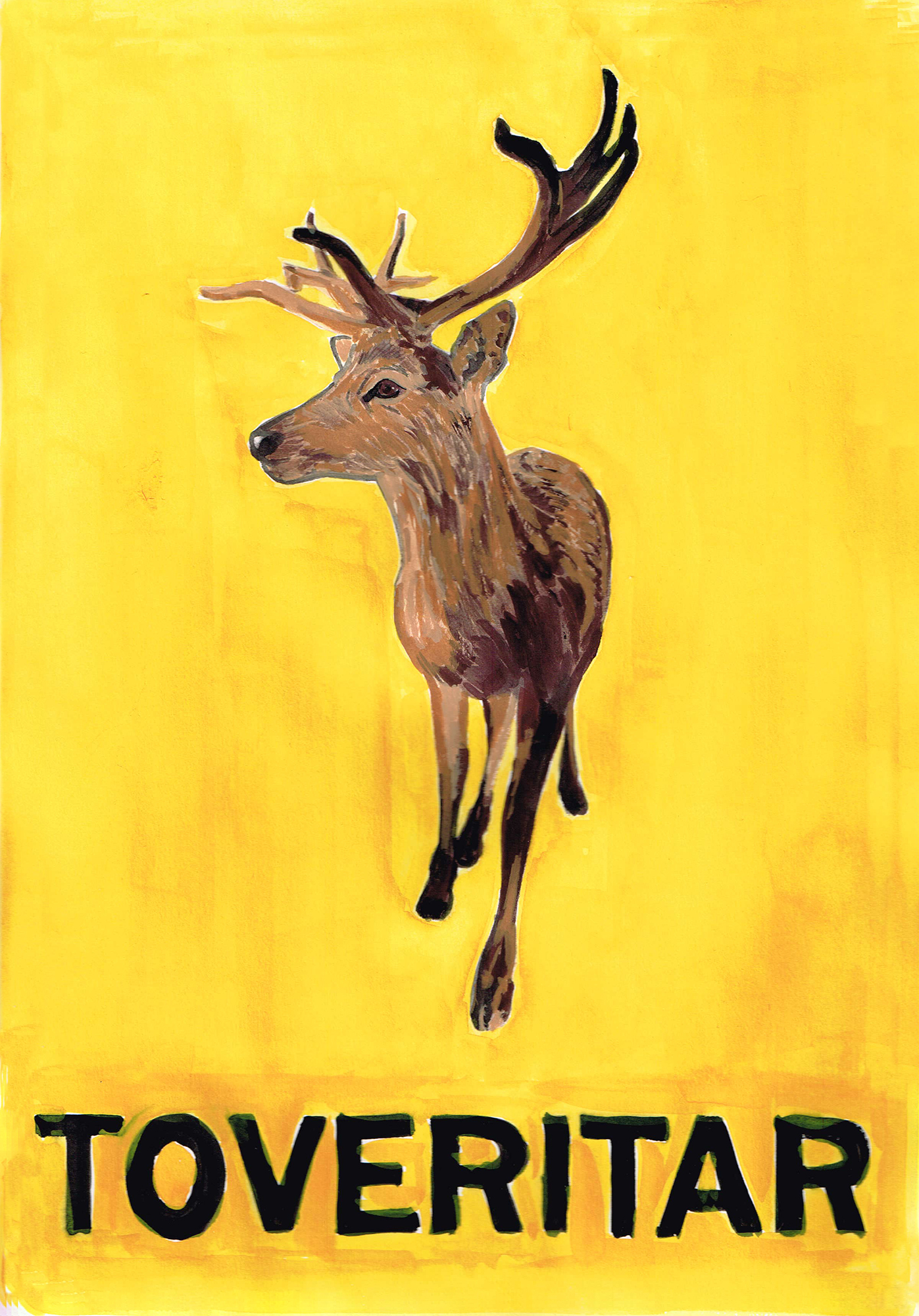

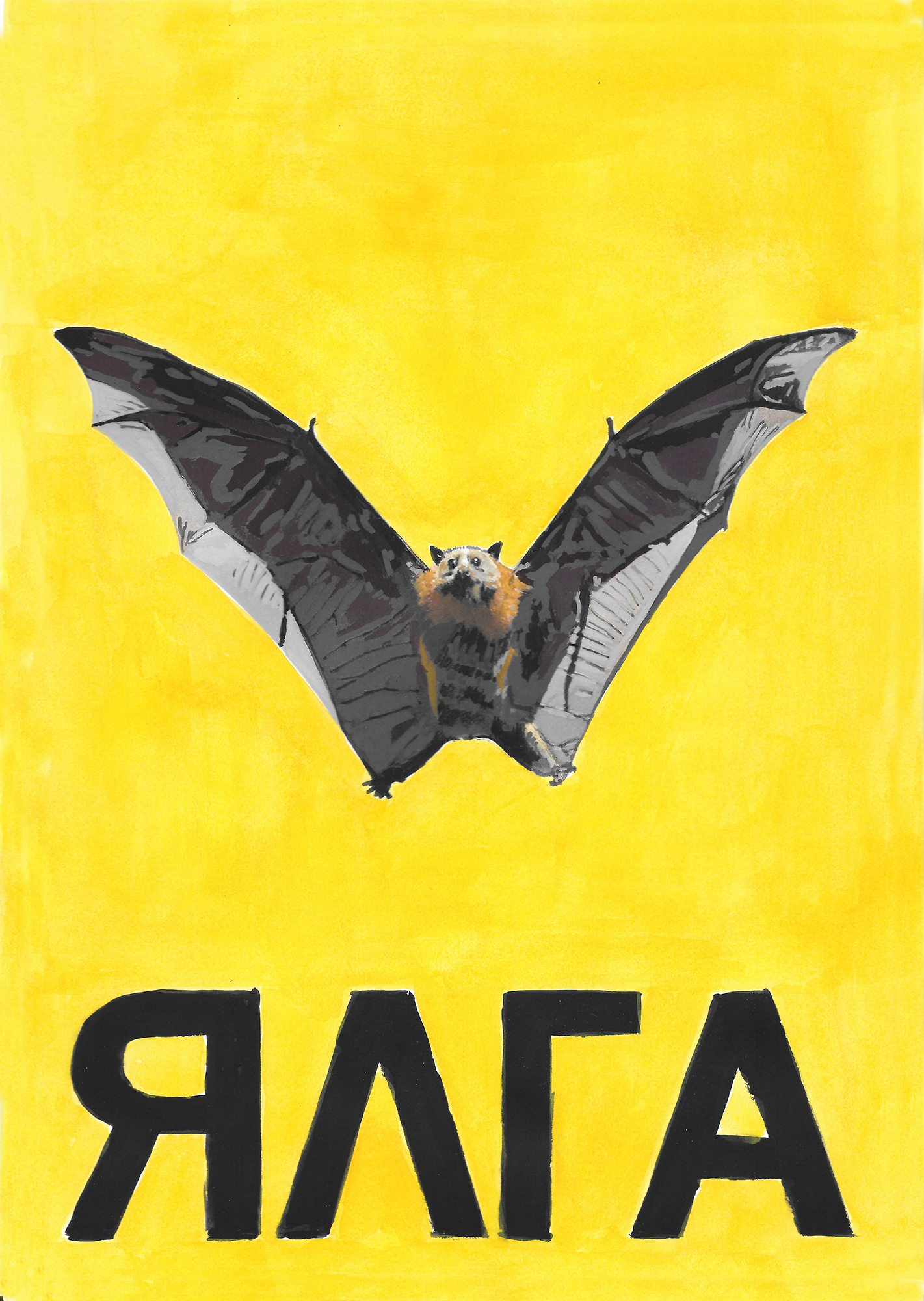

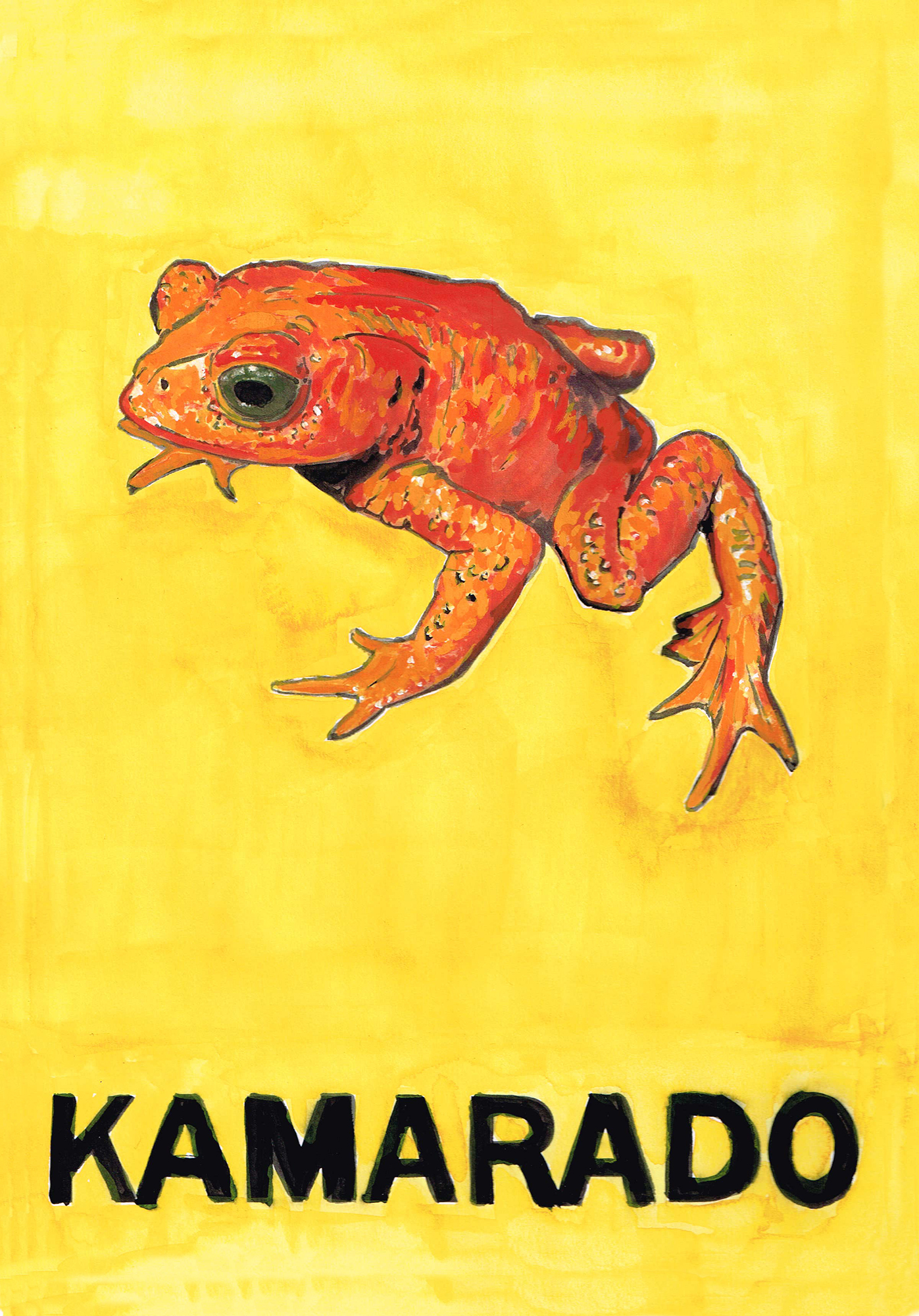

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Comrades in Extinction, installation view, 2020-2021, Gouache on paper [courtesy of the artist]

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Comrades in Extinction, installation view, 2020-2021, Gouache on paper [courtesy of the artist]

SB: Jonas, how would you compare this with the Collectivize Facebook (2020–present) project, in which, together with human rights lawyer Jan Fermon, you are staging pre-trials to collect signatures of co-claimants before filing a complaint against Facebook to the UN Human Rights Council?

JS: Collectivize Facebook is an example of an attempt to create a model to prosecute transnational corporations, within an existing legal structure, whereas the work we’re doing with the CICC is about reconceptualizing these legal infrastructures from the very beginning, by putting the law on trial, as such, and building from there.

SB: How did you envision the court as an object of representation? Once you put the court into the space of art, it becomes a performative act—but with concrete propositions that Radha has described as bringing rights back to earth.

JS: The first sketches [I made] in Radha’s book were an attempt to think through what would be the form of a tribunal, when the notion of rights is replaced by the principle of interdependency, which also changes our relationship to past and future.

For example, the moment a rainforest is harmed in the present at once echoes an ongoing structure of expropriation and commodification that has a longer history. Radha has spoken of [the] climate crisis as one that begins with colonialism. But, while these crimes in the present echo that past, they also harm our interdependent relations with future unborn humans, animals, and plants. Compared to the current rights regime, the notion of relationality allows us to propose a fundamental equality between past, present, and future.

To recognize fellow ecosystem workers as political actors with whom we share an existential struggle really influenced the design of the court, which is built from evidence of climate crimes: painted evocations of extinct animals, woven extinct plants, and the gathering of different ammonite fossils—literally, the fossil in fossil fuels. By creating a chrono-political arena in which different scales of time are assembled in parallel, we tried to express the fundamental equality between different ecosystem workers, a term that we used to avoid having to speak continuously between human, nonhuman, other-than-human, or more-than-human, which centers that human prefix in “human rights” that Radha challenges.

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), installation view, 2021 [photo: Ruben Hamelink; courtesy of the artist, and Framer Framed, Amsterdam]

SB: There was a moment in proceedings when the question of what this trial was doing came up, which speaks to the perception that these events are gratuitous performances lacking a concrete outcome. How would you respond?

JS: The underlying ecology of the different organizations we worked with to put together the tribunal is particularly important, because we don’t rely on the art institution as the space that will bring about transformative change. On a very practical level, we commissioned the evidentiary material filed by participating witnesses so that the funding plays a direct role in their own campaigns. It was, and is, about the sharing of struggles, not the exhibition of them.

We see the court as one of many components—part of a broader ecology of struggle, with artists, cultural workers, organizers, activists, and progressive political movements that are trying to redefine a framework for intergenerational climate justice. I think our public jury represented that. There were different activists and organizers, including organizations [that] contributed to building the cases, together with long-term researchers, organizers, and activists from the field of progressive law—people from municipalities working with questions of sustainability, and those from more traditional institutional perspectives.

For me, the experience of witnessing some of the peoples’ tribunals in Manila, organized by the UGATLahi Art Collective, was very important. Even if the court doesn’t have any direct executive power, it has a power of the imaginary, because it helps to collectively remember the possibility of justice, and actively think about what it would look and feel like, what it means to collectively work for it, and who stands alongside us in that process. In a world where the notion of justice is perpetually absent, this is important. But, of course, it raises the question of what structures or alliances can be proposed to turn that imagined justice into a reality, because if we only invoke the possibility of justice but never deliver it, it becomes a very poisonous imaginary.

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Comrades in Extinction, installation view, 2020-2021, Gouache on paper [courtesy of the artist]

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Comrades in Extinction, installation view, 2020-2021, Gouache on paper [courtesy of the artist]

SB: Speaking of funding, and thinking about CICC as being part of a much broader tapestry of intersecting networks, could you comment on your position in relation to the systems you’re challenging? Take the proceedings against the Dutch state, which brought a case against the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation and the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy. Although representatives from both ministries were absent, the state was present in the fact that the CICC project was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.

RD: I come to this from a more philosophical perspective. I think that question—The Ministry of Education is funding you, so how can you be critical?—can be turned around by claiming that we are also taxpayers, and so are the members of the jury who were present. But that is [a] somewhat frivolous argument—frivolous because liberalism is based on individualism and therefore asks you to take an individualistic position. No matter which sphere you look at—whether art or academia—we are social beings. We live in a society in which our constitutions are given to us—given to us because we are always born into a pre-existing society, no matter the nature of that society. And there are always contradictions between the social order and individuals. For example, I was born a woman into a very patriarchal society, with a patriarchal family that looked after me and educated me. Should I now say my whole family is rubbish because I am against patriarchy?

It is the same thing [with] my work at the university. The UK is exceptionally neoliberal, and I have to make my choices. As long as I’m teaching and publishing, I get my salary that pays my bills, so that I can do my social justice work with other people. We make these compromises in recognition of the fact that we are social beings, and while there will always be social constraints to what we do—and, of course, we have to change those things—we cannot do that by stepping outside of society, because we are still living in it.

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), installation view, 2021 [photo: Ruben Hamelink; courtesy of the artist, and Framer Framed, Amsterdam]

JS: I think that is the tension between working and organizing … within a context that is perpetually compromised. I feel that we are always working between worlds; between the world as it is and the world as we imagine and try to organize [it] into being. That amounts to a continuous negotiation. You use one relative opponent to critique, or undermine, another; you seek the gray zones and conflicts within a system that can provoke meaningful change.

When it comes to the Dutch state apparatus, fortunately there are comrades, leakers, and whistle-blowers who operate within the cracks that enable us to access common resources and [to] organize organizational artworks such as the climate tribunal or the alternative parliaments. The name of the CICC itself is a critique of the International Criminal Court, the “ICC,” which claims the Netherlands as a neutral arbiter that speaks law, or claims law or jurisdiction, over other territories but rarely challenges its own legality, whereas the cases we bring to the CICC all have a direct relation to the Netherlands. So, it’s also a turning inwards of the question of justice.

But it’s never a clean or clear-cut process, because even if we maintain fundamental red lines, others inevitably arise. I felt this very strongly when we successfully threatened with a boycott of the Sao Paulo Biennial, during the 2014 Gaza bombings—when we demanded that Israeli funding be removed from the exhibition. Many of our Brazilian comrades supported our case but also highlighted Petrobras, one of the biennial’s main funders, which is the national oil company responsible for the disappearances of thousands of Indigenous peoples; or Global Network, the TV network that put in place every military junta in the history of Brazil. That is the question we are always dealing with, both strategically and imperfectly.

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), installation view, 2021 [photo: Ruben Hamelink; courtesy of the artist, and Framer Framed, Amsterdam]

SB: What you’ve both described, in terms of working from within a system to reroute it, speaks to questions of reform and abolition. Do you dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools, or do you build a new house altogether?

It recalls a discussion on the podcast for the Oxford Human Rights Hub between legal scholars Gautam Bhatia and Joel Modiri on the colonial influences that shaped the constitutions of India and South Africa, that centered on whether to write a new constitution altogether or work with what [was already in place].

RD: A constitution, which structures the functioning of the state, does two jobs: One is to articulate what kind of nation we want to be, and the other is to distribute state power, how state power will be exercised. So, when people talk about constitutional debates, they usually focus on the aspirational aspect. Do I want India to be a secular and egalitarian democracy? Of course I do. But does the Indian constitution distribute powers of the state in such a way [to allow] that? No. This is an important difference that people often forget. Constitutions are always born out of a political history. Republicanism did not fall from the sky. It came out of the French Revolution. Similarly, the Indian constitution emerged from the triumph of liberals over anti-liberals in the colonial struggle. There was another constitution, written by the radical strand in the independence movement, that recognized the country’s historical cultural plurality and linguistic differences, [and] which has been forgotten, due to active suppression of that tradition in how post-Independence history is written. I’m sure you’ll find similar stories in every country.

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), installation view, 2021 [photo: Ruben Hamelink; courtesy of the artist, and Framer Framed, Amsterdam]

JS: I’ve been involved in a political party in the Netherlands that used to be called Article 1, the anti-discrimination principle in the Dutch constitution. To name themselves Article 1 was a way to bring into public consciousness that the article exists but is not enacted, which relates to the aspirational dimension that Radha was mentioning and how the state apparatus can interpret the constitution for the benefit of dominant regimes of power. In the case of the War on Terror [these initiatives were] enacted through blacklisting people, making them stateless by withdrawing their right to have passports and bank accounts. If they are no longer citizens—or, even, no longer human—then constitutional frameworks no longer apply to them in any formal way.

SB: Which relates to the work of the New World Summit, and the refusal of that reduction.

JS: In the case of the NWS, it was very much about trying to reconceptualize who or what exactly defines the us in the us-versus-them dichotomy perpetuated by the War on Terror. And, in a way, [the project] started from the question [of whether] it was possible for citizens whose countries waged the War on Terror to have more in common with blacklisted groups criminalized in this war than [with] the states that acted or spoke in our name. It was about trying to demythologize this narrative link between citizen and state, and to recompose [with what] communities or collectives we truly share purpose.

That [effort] informs something [about] the process of collective enactment in the CICC. It’s not only about witnessing someone who tells you that the legal structure could be different, that we can replace the notion of rights for a more fundamental notion of interdependency, but [also about the ability] to enact it collectively, to create an embodied experience of the world as it could be. It’s about evoking a reality that exists, or lingers, within the reality of capitalist capture, which also relates to the relationship between the legal institution and the art institution. Because, if we do our work right, slowly the legal court becomes this powerless theater, and the theater becomes the court that we didn’t dare believe could exist.

RD: We couldn’t have done this in any real legal institution. It needed an art space.

SB: That this could be possible [only] in the space of art also relates to the broader context of where that institution is located. For all we know about the West, and even if hosting or funding the CICC could be seen as a way to wash an institution or state of its guilt, it arguably would not have been possible to stage the CICC in Hong Kong, for example, against the Chinese state, because the National Security Law is actively being used to extinguish dissenting voices across the fields of culture and journalism.

These shifting dynamics are probably worth mentioning, and, of course, they aren’t so clear cut, given how the UK has passed laws that equal those of the NSL in the past year.

RD: Ten years ago, we could have done a lot of things in India that I would not dream of doing now, because it would simply not be possible. By the same token, I don’t take these so-called Western liberal societies for granted. Europe is the home of fascism as much as [of] democracy. If there are still freedoms, it simply means that the establishment is not threatened enough to clamp down. But make no mistake. There will be clampdowns. We also cannot afford to forget the fact that there are large sections of society where such freedoms don’t exist. And nothing is inevitable. So, let’s make the best use of the space and time that we have now.

Stephanie Bailey is editor in chief of Ocula magazine, a contributing editor at LEAP, and a regular contributor to Artforum International, Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, and dɪ’van: A Journal of Accounts. Formerly the senior editor of Ibraaz, where she worked 2012–2017, Bailey is also a member of the Naked Punch editorial committee; a managing editor of Podium, the online journal for M+ in Hong Kong; and the current curator of Art Basel Conversations in Hong Kong.

Radha D’Souza is a professor of International Law, Development and Conflict Studies at the University of Westminster (UK). D’Souza is a social justice activist who worked with labor movements and democratic rights movements in her home country, India, as an organizer and activist lawyer. With artist Jonas Staal, she co-produced the exhibition Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021–2022), commissioned by the art space Framer Framed, Amsterdam. She is author of What’s Wrong With Rights? Social Movements, Law and Liberal Imaginations, which forms the basis for the exhibition; and of Interstate Disputes Over Krishna Waters: Law, Science and Imperialism. She works with the Campaign Against Criminalising Communities (CAMPACC) in the UK. D’Souza has a BA in philosophy from Elphinstone College (University of Mumbai) and an LLB from New Law College (University of Mumbai); she completed her PhD in Geography and Law at the University of Auckland. She has taught in the universities of Auckland and Waikato, and practiced law in the High Court of Mumbai in the areas of labor rights, constitutional and administrative law, public interest litigation, and human rights.

Jonas Staal’s work deals with the relations among art, propaganda, and democracy. He is founder of the artistic/political organization New World Summit. With Florian Malzacher he co-directs Training for the Future, and with human rights lawyer Jan Fermon he initiated the lawsuit Collectivize Facebook. With writer and lawyer Radha D’Souza he founded the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes, and with Laure Prouvost he is co-administrator of the Obscure Union. Exhibition projects include Art of the Stateless State (Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 2015), After Europe (State of Concept, Athens, 2016), The Scottish-European Parliament (CCA, Glasgow, 2018) and Museum as Parliament (with the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 2018-ongoing). His projects have been exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, M HKA in Antwerp, Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and the Nam June Paik Art Center in Seoul, as well as at the 7th Berlin Biennale, the 31st Bienal de São Paulo, and the 12th Taipei Biennial. His publications include Stateless Democracy (with co-editors Dilar Dirik and Renée In der Maur), Steve Bannon: A Propaganda Retrospective, Training for the Future Handbook (with co-editor Florian Malzacher), and Propaganda Art in the 21st Century. Staal completed his PhD research on propaganda art at the PhDArts program of Leiden University, the Netherlands.