Imagine New Monuments

Share:

“Together,” Delcazel Playground, Opelousas and Verret [courtesy of Paper Monuments]

I. RECONSTRUCTION AND MONUMENTAL EFFECTS

In 2017, Sue Mobley and Bryan C. Lee Jr. formed the organization Paper Monuments with a small group of friends and colleagues. Rooted in gratitude to the generations of activists who came before them, the organization set out to tell the untold stories of New Orleanians: individuals from there, who immigrated there, and those committed to supporting the culture and infrastructure of the city. Paper Monuments’ goal was to represent the voice of the people of New Orleans, fueled by the understanding that art—whether visual, performative, or written—has one of the most important jobs: telling silenced stories, large and small.

In New Orleans—home to people of the Natchez and Chitimacha Tribes, the Houma Nation, and individuals from Africa, the Caribbean, Latin America, Vietnam, Spain, France, and many more regions—recent events have heightened conversations about whose voice is heard and who is represented within the public sphere. Until May 2017, Robert E. Lee, P.G.T. Beauregard, Jefferson Davis, and the White League were honored on pedestals at the city’s major intersections. Meanwhile, individuals such as Dorothy Mae Taylor, John O’Neal, and the victims of the fire at the UpStairs Lounge are much less acknowledged, though these people helped make New Orleans the city it is today.

For over a year, Paper Monuments organizers and volunteers wheatpasted dozens of posters that highlighted local heroes and groundbreaking moments onto buildings throughout New Orleans, capturing the attention of residents and visitors. Most of the posters were tabloid size and consisted of a story and artwork, although some were much larger at about eight feet tall and four feet wide. They served as reminders to onlookers that the history of civil rights is layered and complex in New Orleans, as it is in many areas of the US and the world, but also that there are countless stories of bravery to celebrate within this history.

The promise of Reconstruction in the South immediately following the Civil War set a tone of freedom lost, while also laying the foundation for work that could create justified change. Although the Louisiana state constitution of 1864 abolished slavery, members of the Confederacy and their families worked hard to keep African Americans in a disadvantaged place by making it nearly impossible for them to own land, work for a living wage, or gain access to education.

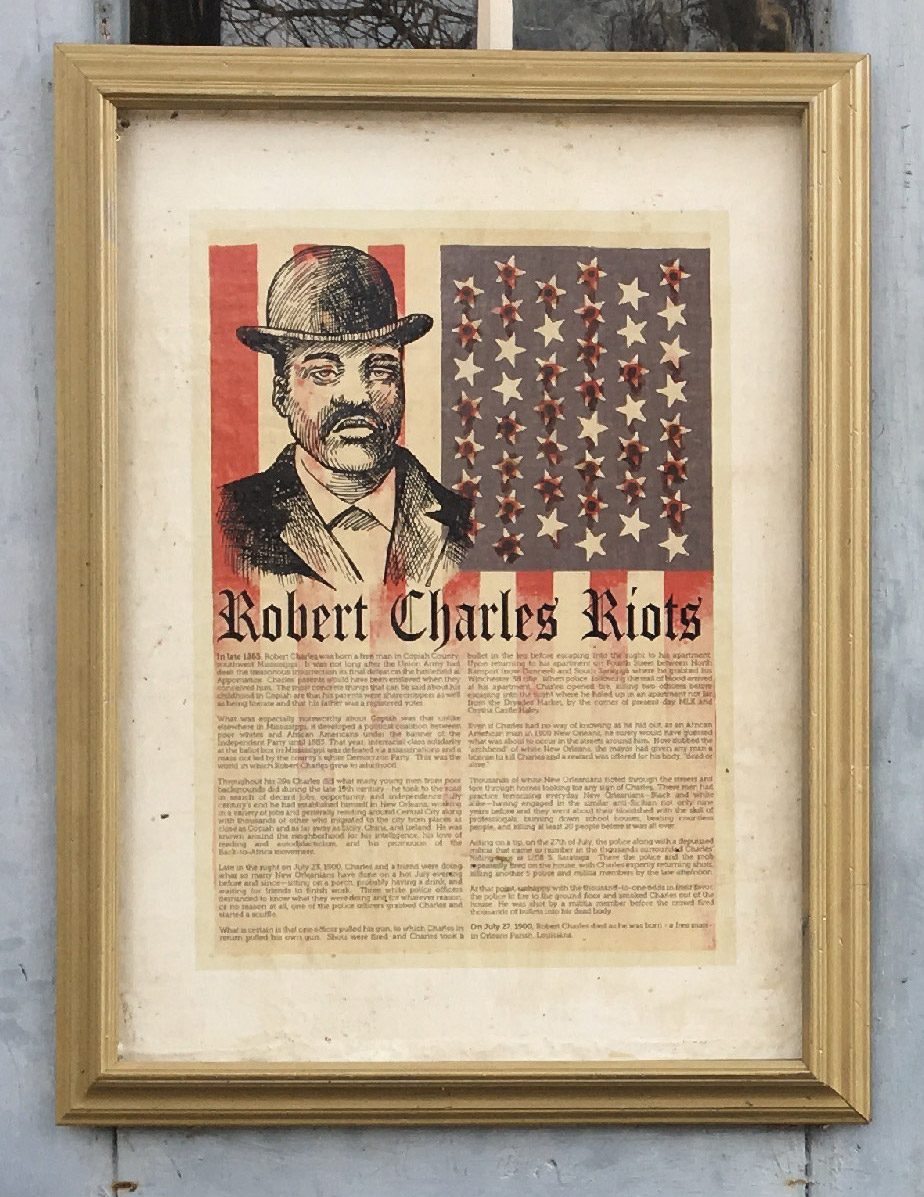

“Robert Charles Riots, 1460 N. Robertson Street,” from Framing Histories [courtesy of Paper Monuments]

However, civil rights campaigns in Louisiana were some of the earliest in the country. Banding together, African Americans created such newspapers as L’Union and The New Orleans Tribune—heralded as the first black-owned daily. These papers aided the cause for freedom among people of color by publishing stories of their intellect and greatness. Other papers around the US followed suit, such as the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, where Ida B. Wells worked and eventually became editor and co-owner. These newspapers were founded on the principle that sharing stories increases agency—media, as we know, can define morality, policy, and the general tenor of an era. Although a new state constitution was adopted in 1868 to eradicate black codes, grant equal access to public spaces, allow African American men to vote, and integrate public schools, these laws were not upheld in most of Louisiana. In fact, the laws led to an increase in the formation of white supremacy groups and vigilante violence toward African American communities. The Louisiana state constitution of 1898 and civil court cases eventually overturned many of the constitutional changes from 1868, and soon Jim Crow laws usurped steps toward progress.

Almost a decade after the extreme devastation and displacement caused by levee failures during Hurricane Katrina, government officials Bobby Jindal and George W. Bush asserted that New Orleans was “back and better than ever,” but most residents were not in agreement. The reverberating effects of an unjust system remain clear—according to The Data Center in New Orleans, while there are many indexes that signal positive changes in quality of life for New Orleanians since 2004, incomes and home-ownership remain lower for African Americans in the city and “as recently as 2016, individuals detained in the Orleans Justice Center (or Orleans Parish Prison) were nearly four times more likely to be black than white.”1 In 2017, as the city was gearing up to celebrate the colonial French founding of La Nouvelle-Orléans’ tricentennial and community members gathered to reflect on generations of leaders in New Orleans, Mayor Mitch Landrieu issued a statement calling for the structured dismantling of four Confederate monuments in New Orleans. This move came in response to the mass shooting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston in 2015, as well as growing local pressure. News sources across the country published Landrieu’s assertion that there are many groundbreaking figures to honor in New Orleans, and “To literally put the Confederacy on a pedestal in our most prominent places of honor is an inaccurate recitation of our full past, it is an affront to our present, and it is a bad prescription for our future …. Centuries old wounds are still raw because they never healed right in the first place. Here is the essential truth: we are better together than we are apart. Indivisibility is our essence.”2

Mayor Landrieu’s proclamation to remove the monuments ignited debates across the country and aided in the removal of some monuments in cities including Chapel Hill and Charlottesville. Whereas a statement from a city leader can inspire hope, though, the reality unfolding in the city was different—on any day that fell between the proposed removal and actual deinstallation of the monuments, individuals could be seen guarding these statues, often waving the Confederate flag. Because of damage inflicted upon the property of local companies, regional contractors took the job to remove the monuments in New Orleans, and police officers adorned in riot gear helped dismantle them. In an interview earlier this year, Sue Mobley described how more than 2,000 individuals marched in the streets of New Orleans to support the monuments’ removal. As the group turned a corner to find hundreds of individuals in support of these symbols of white supremacy, it became “a real moment of coalescence of what this space could do, would do, to defend its right to be, and to be the way we see it.”

Moments of social and political rupture have long carved a path for important cultural projects—one could consider the Gutai group in Japan, and even the documenta exhibitions in Germany, among many others.

Although each is different in form and process, such projects and movements represent a desire to create a new foundation and a new future, but they do not always have defined goals. An open mind and an active imagination help us understand people around us, help us acknowledge the histories that were erased, and keep us engaged with our communities—qualities that have been the strength of Paper Monuments.

II. PROJECTED, PAPER, AND PUBLIC MONUMENTS

Shortly after the dismantling of the Lee monument, Paper Monuments began to take shape. Projecting History kicked off the vision of Paper Monuments at Tivoli Circle, where the Robert E. Lee monument stood, in August 2017, and its temporary nature foregrounded how they would continue to engage public space. As the event came together, Paper Monuments joined forces with community activists addressing the need for stronger and more realistic representation of the people of New Orleans, with several of the organization’s members also participating in groups such as Take ’Em Down NOLA—a group focused on the removal of white supremacist monuments.

“La Village des Chapitoulas, 424 Josephine Street,” from Framing Histories [courtesy of Paper Monuments]

All the while, debates surged among people who believed that monuments of all kinds should be honored and kept in place. Although the work of Paper Monuments and that of many others simmered around these topics for years, this particular moment of rupture—perhaps the moment foremost in the public eye—gave the group an opportunity to “elongate the conversation.” Similar to projects such as WWNO radio’s series TriPod: New Orleans at 300 and “A Peoples’ Guide to New Orleans: Resistance In the Tremé,” a walking tour organized by Elizabeth Steeby and Lynnell Thomas for the American Association of Geographers, Paper Monuments also highlighted New Orleans histories through the contributions of various individuals, sharing the city’s history beyond commonplace narratives.

The project aimed to encourage dialogue across generations and neighborhoods, and was deeply inspired by initiatives in other cities such as Monument Lab in Philadelphia. Continuing their public outreach, the organization set up tables at community events, art openings, and local businesses, where they handed out blank tabloid-sized posters to residents with the following instructions: to imagine what one most wanted to see representing their city, to title this new monument, and to explain why this story needed to be told. Paper Monuments was diving into a dynamic history of posters and newspapers used to disseminate information artistically, socially, and politically, as done by groups from the Italian Futurists to the Black Panthers.

As Lee described in an interview for a local digital publication, Via Nola Vie, Paper Monuments also chose to use paper as its primary medium because “paper is synonymous with identity [i.e. get your papers to show who you are, where you belong, etc.]; it’s an identity consideration, and we are asking people to define what our city’s identity wants to be.”3 The public proposal posters were one of the first phases of Paper Monuments, and they continue to be among the most recognizable and inspiring tools of the project. By asking individuals to “imagine new monuments,” people were encouraged to talk to one another, to consider the removal of Confederate monuments a “tension point for bigger conversations,” as Mobley described, and to realize their agency in contributing to a more just society.

Alongside the development of the public proposals, Mobley and Lee invited writers and storytellers to narrate histories of social justice in New Orleans, and visual artists responded to their stories. These posters were distributed to local libraries, bookstores, and cultural institutions, and were available for free at each event where Paper Monuments was present.

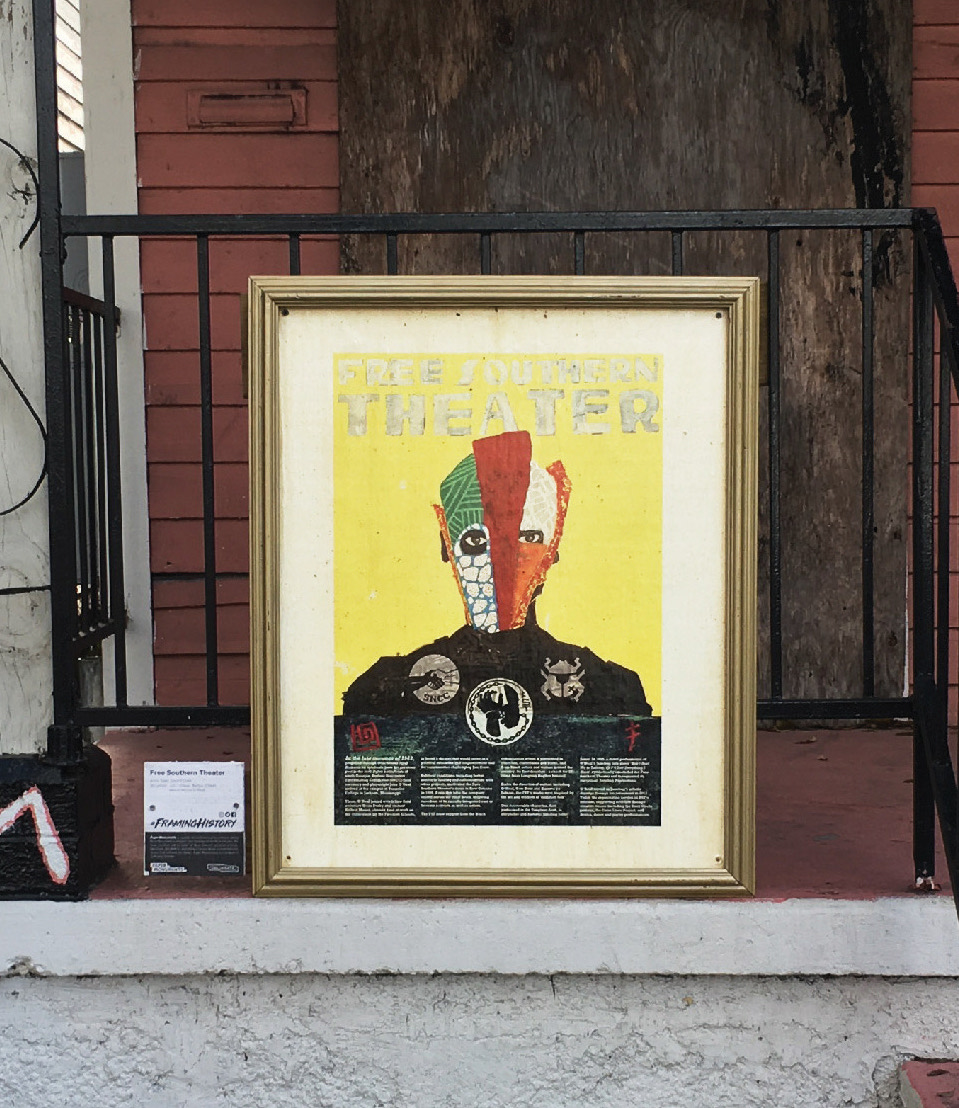

“Free Southern Theater, 2416 Jackson Avenue,” from Framing Histories [courtesy of Paper Monuments]

The poster campaign’s stories included histories of groups such as the Free Southern Theater—a theater action group founded to support Southern activists through education and empowerment—as well as people involved in such events as the Streetcar Protests of 1867 and the Desire Standoff of 1970, who are remembered through the posters for their bravery and humanitarian advances. New Orleans artists D. Lammie-Hanson, Hannah Chalew, Sean Gerard Clark, and Tiffany Lin, among many others, created artwork that represented and responded to narrated histories by leaders, writers, and historians such as Malik Rahim, a former Black Panther; writer Lydia Nichols; and geographer and historian Richard Campanella. The storytellers and artists came from a variety of backgrounds, and the events described in the poster campaign spanned more than a century. As Paper Monument’s engagement with the community grew, the organization also started publishing Paper Trail, a newspaper that shared the stories and information about the poster contributors, and also promoted the group’s events.

Scaling up from the posters and newspapers, Paper Monuments issued a call for artists to propose actual monuments for a temporary outdoor installation spanning the city. Ten outdoor works were unveiled in spring 2019 as part of the group’s Re: Present series, ranging from watercolors of neighbors displayed in Mid-City to a large metal sculpture of a flourishing plant rising from the ground opposite the Circle Food Store. The outdoor sculptures and posters offered an intervention into public space, but also into the public mindset. Lee’s inquiry “How can we use public art to make public space more engaged?” proved to be a guide for the project. Engaging public works stop people in space and frame them there, in that moment, but they also have the potential to transcend physical boundaries and invite viewers to imagine different geographical and liminal spaces.

III. WHAT’S NEXT?

By the time of its interim report publication in early 2019, Paper Monuments had received 747 monument proposals from individuals ages 3 to 78. After phases of sculptural installation and poster presentations come to a close, the organization began working with the recently reopened New Orleans African American Museum (NOAAM) to host an exhibition of the projects. Claiming Space, an exhibition at NOAAM, opened in early May and featured multiple large posters that were once wheatpasted onto buildings at the corners of Canal, South Rampart Street, and Elk Place in the white-walled gallery of the museum’s administrative building. In the gardens surrounding the museum’s main campus—where the buildings remain closed—nine Re: Present public sculptures were installed.

At the opening reception for Claiming Space, dozens gathered in the gallery. Shortly after introductions concluded, a Take ’Em Down NOLA leader spoke about recognition and about the importance of action. The energy soared in the room as people began yelling. A tipping point had been reached. Can conversations and imagination be considered activism? Can we work together, and independently, to fuel the same mission of amplifying the voices that need to be heard, but through different means?

Regardless of approach, be it art, design, activism, or storytelling, one element holds true—we must create opportunities to work together to imagine our collective future.

Amid the coordination, installation, and maintenance of Paper Monuments’ outdoor public sculptures, Mobley and Lee continued to question the sustainability of the project. With a very small organizing team, they strove to develop the project deliberately and intentionally, asking, “How do you involve many people over time in a way that has meaning, without being extractive?” Ultimately, these projects, which exist as educational platforms, encourage us to think more broadly while harnessing our individuality, prompt us to slow down, and allow us to learn much more about one another. By starting a conversation about the history of Confederate monuments in New Orleans, we make space to address the multilayered histories of freedom for African Americans, immigrant labor rights, citizens’ access to housing and education, and the function of the media today. The individual stories brought to the table during moments of tension have the ability to reveal the past and invite us to imagine more for our future.

“John Thompson, 1502 St. Bernard Avenue,” from Framing Histories, [courtesy of Paper Monuments]

Paper Monuments continues to encourage strong responses to the power dynamics of racial hierarchy—by allowing a multitude of voices the freedom of ideas and approach renders the playing field more fluid and equal. As the project comes to a close, and as we approach more junctures that are reminiscent of the many hopeful moments of Reconstruction, this project inspires us to acknowledge and honor one another now. Whether through a proposal to Paper Monuments, a letter to the mayor, a march on an unjust monument, or a conversation with a friend, we must heed Paper Monuments’ direct call to action: “Own the stories that society quiets.”

Emily Wilkerson is a writer and curator based in New Orleans, where she writes about contemporary art and culture as a departure point for exploring our shared social and cultural experiences around the globe. Wilkerson most recently served as deputy director for Curatorial Affairs at Prospect New Orleans and has contributed to publications including Art in America, Pelican Bomb, Burnaway, and multiple exhibition catalogs. She is most interested in the ability of artists of all types to tell the untold stories of our lives.

References

| ↑1 | Allison Plyer and Lamar Gardere, “The New Orleans Prosperity Index: Tricentennial Edition,” The Data Center, May 8, 2019, via web |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Mitch Landrieu, “We can’t walk away from this truth,’” The Atlantic, May 23, 2017, via web |

| ↑3 | Kelley Crawford, “Paper Monuments: Story Boards and monuments for all,” Via Nola Vie, March 06, 2018, via web |