Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête

Share:

In recent years, Huguette Caland (1931–2019) and a group of women artists of Lebanese origin, working in abstraction—including Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916–2017), Etel Adnan (b. 1925), and Simone Fattal (b. 1942)—have become increasingly familiar thanks to Western art institutions’ growing curiosity about Arab modernism. Such international recognition came late in Caland’s life. Her first large-scale solo museum exhibition, at the Tate St Ives, opened mere months before the artist’s passing in 2019.

Caland embarked on her artistic journey later in life than most, enrolling as an art student at the American University in Beirut in her thirties, already a wife and mother and having recently lost her father, Bechara El Khoury, Lebanon’s first president. What followed was a 50-year career of constant exploration and experimentation, one uninhibited by any particular medium or form. Despite living in Paris for most of the 1970s and 1980s, and eventually settling in California in 1987, she was somewhat marginalized by her adopted art scenes for decades. In contrast, Caland exhibited regularly in Beirut, where her talent has long been recognized, and as part of international group exhibitions of Lebanese artists. Caland’s decision to leave her home and family at the age of 39 to pursue her career presents a particular allure, but it is worth resisting the temptation to frame her as an escapee, fleeing her repressive local context. She would be more accurately approached as part of a cosmopolitan elite, which saw itself at home in the world and within multiple art scenes.

Huguette Caland, Figurine, 1983, clay and acrylic paint, 13 x 6 x 3 inches[courtesy of The Drawing Center, New York]

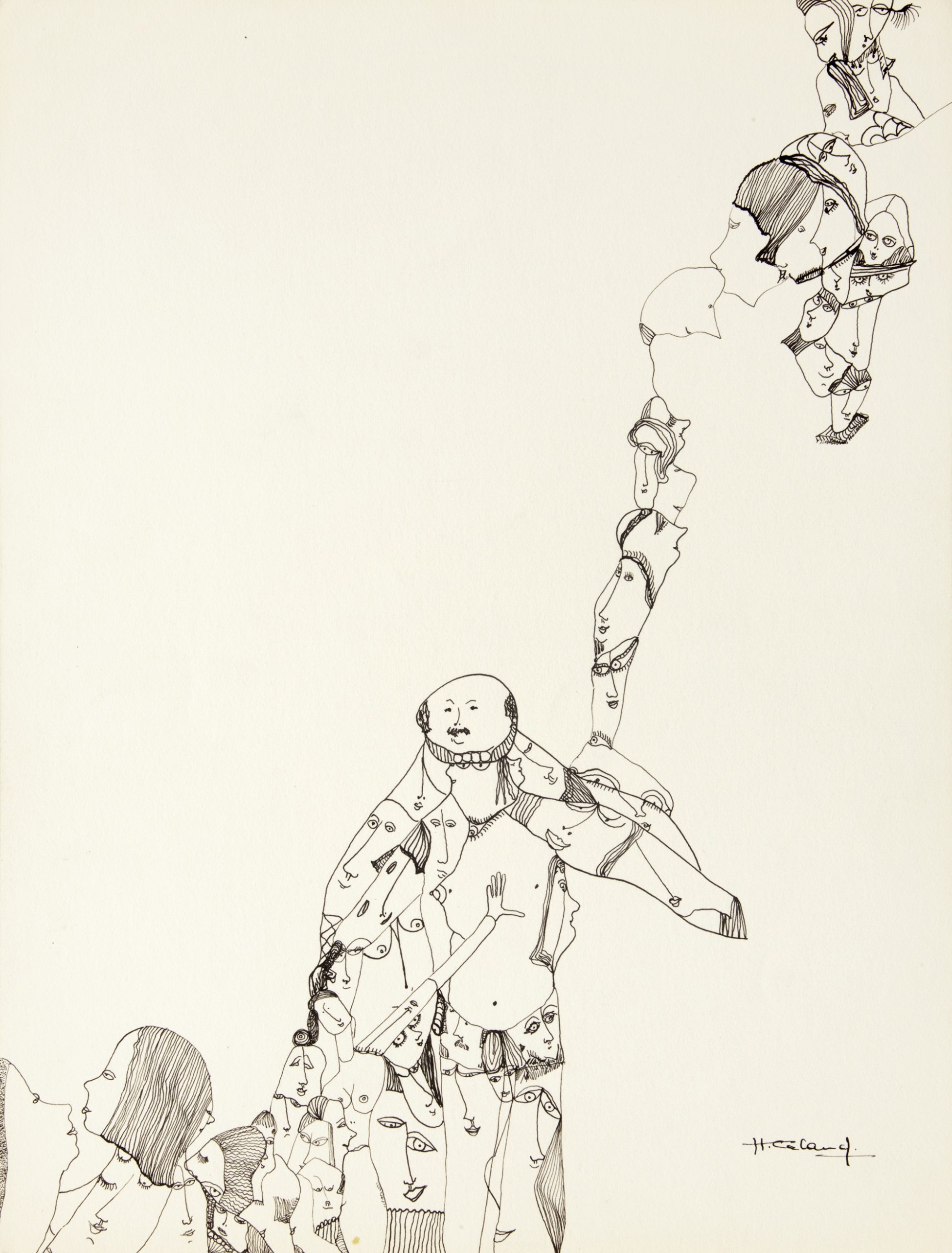

Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête has an airy, buoyant quality, which is remarkable for an exhibition encompassing so much of the artist’s career. It includes paintings, drawings, painted caftans, sculptures, and notebooks. As the title—an appellation borrowed from a 1983 color pencil drawing—suggests, much of Caland’s work is about connection and intimacy; the encounter between bodies; the endless points of contact as bodies meet, merge, become almost indistinguishable. The identities of her subjects are never singular or defined, shaped instead by each body’s relationship to another. Caland’s characters multiply, reproduce, fragment, unfold, sprawl, and spread. In an early ink drawing, Mustafa, poids et haltères (Mustafa, Weights and Dumbbells) (1970), her lover’s head anchors the work as his body expands up and out across the page, an amalgamation of characters, a fusion of limbs, distorted, amputated, compressed, faces squashed together, merging to make a disfigured whole. This unravelling that cannot be contained within limited boundaries exemplifies the artist’s vision. Categories and distinctions are challenged—or, even better, ignored. Likewise, an ambiguously gendered couple in 1er Dessin encre de Chine, hiver (First ink drawing from China, winter) (1971) is rendered from a collage of faces, their eyes peeking out of their torsos, arms, even their palms and fingers.

These early drawings, with their delicate precision, might first appear quite distinct from the artist’s paintings of the same period; Bribes de corps (Body Bits) (1973), Caland’s most celebrated series, is a bright, voluptuous study of curves and creases. In contrast to the crammed figures that float over the crisp white page, occupying a limited space in their confinement, these body parts are all-consuming. Abstracted to the point of gestural strokes, the fleshy, sensuous landscapes roll freely across the canvas, filling it with corpulent abundance. Viewing these works alongside each other captures the range of Caland’s experimentation with line and human form. Again, it is the point of contact, the subtle—and sometimes not so subtle—space of connection, that is so captivating. Bribes de corps, like her later pencil drawings, are astute examinations of the gestured, the implied, that are at once sensuous and humorous. As in so much of Caland’s work, their mischievous, playful energy opens a space of exploration and innovation.

Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête, installation view, The Drawing Center, New York, 2021 [photo: Daniel Terna]

Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête, installation view, The Drawing Center, New York, 2021 [photo: Daniel Terna]

Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête, installation view, The Drawing Center, New York, 2021 [photo: Daniel Terna]

It is perhaps this unrelenting wit, this lack of preciousness, that makes Caland’s investigation of the female form so intriguing. In the 1992 mixed media series, Homage to Pubic Hair, the artist began shifting this study toward a different direction; geometrical figures branch out from one another, sprouting limbs and shooting tufts of corkscrew hair every which way. Some form constellations, while others unfold into patchworked plots of farmland in which body parts and hair have been planted, mingling through seeping color washes. Once again, the landscape cannot be distinguished or separated from the corporeal elements; however, these artworks also anticipate the gradual dispersal of the human form as Caland’s lines straighten out into a grid.

The artist’s approach to her own body, to the voluptuousness of its form, shaped her work. She embraced her fuller figure despite societal norms that compelled women of her generation to occupy less space, to adhere to restrictive notions of beauty and elegance. As such, her body was not merely the subject of her work, but often served as her canvas by way of the caftans she designed for herself. In doing so, Caland became part of a tradition of women artists turning their own self-presentation into a significant aspect of their aesthetic project; like Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) and Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) before her, she developed a personal style that defied expectations of fashion and femininity. In the late 1970s, she collaborated with designer Pierre Cardin (1922–2020) on a line of androgynous garments akin to those she created for herself. These shapeless caftans would simultaneously hide and reveal her form, decorated with body parts—sometimes the intimate ones that clothes are intended to cover. But the X-ray is incomplete; not everything is exposed at all times, only that which is absolutely necessary. The rest is left for us to imagine.

Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête, installation view, The Drawing Center, New York, 2021 [photo: Daniel Terna]

In the final decades of Caland’s career, her lines began to transform. Grids replaced curves and perspective shifted, allowing us a bird’s eye view of her increasingly intricate landscapes. In a series of large-scale cartographies produced in the first decade of the 21st century, Caland worked on small sections of unstretched canvas, folded so that she was unable to visualize the whole until the piece was complete. Reminiscent of the small maps she would produce during her travels, these patchworks, developed through a process of constant unfolding, reference the vast and varied topographies of Caland’s life.