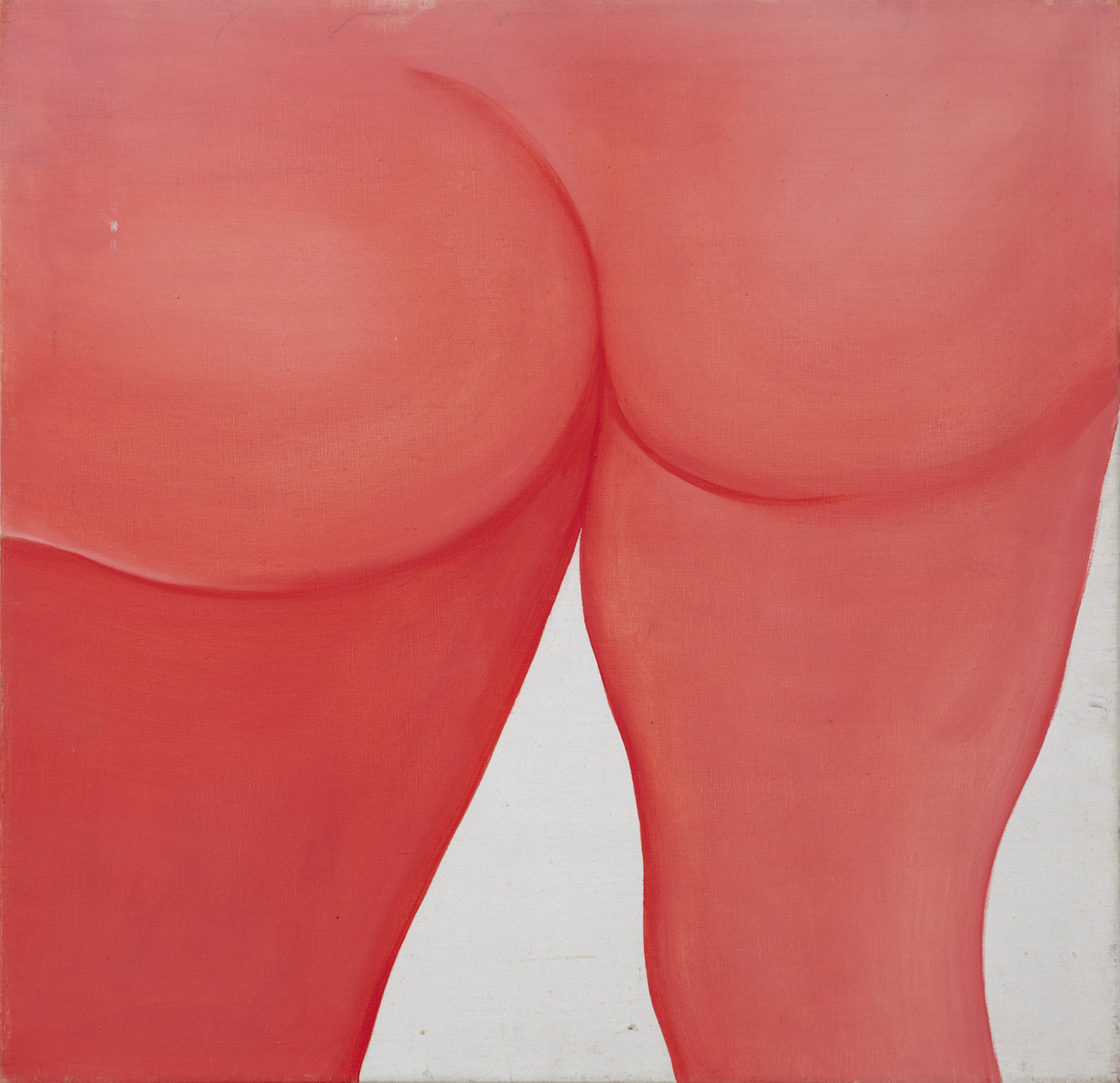

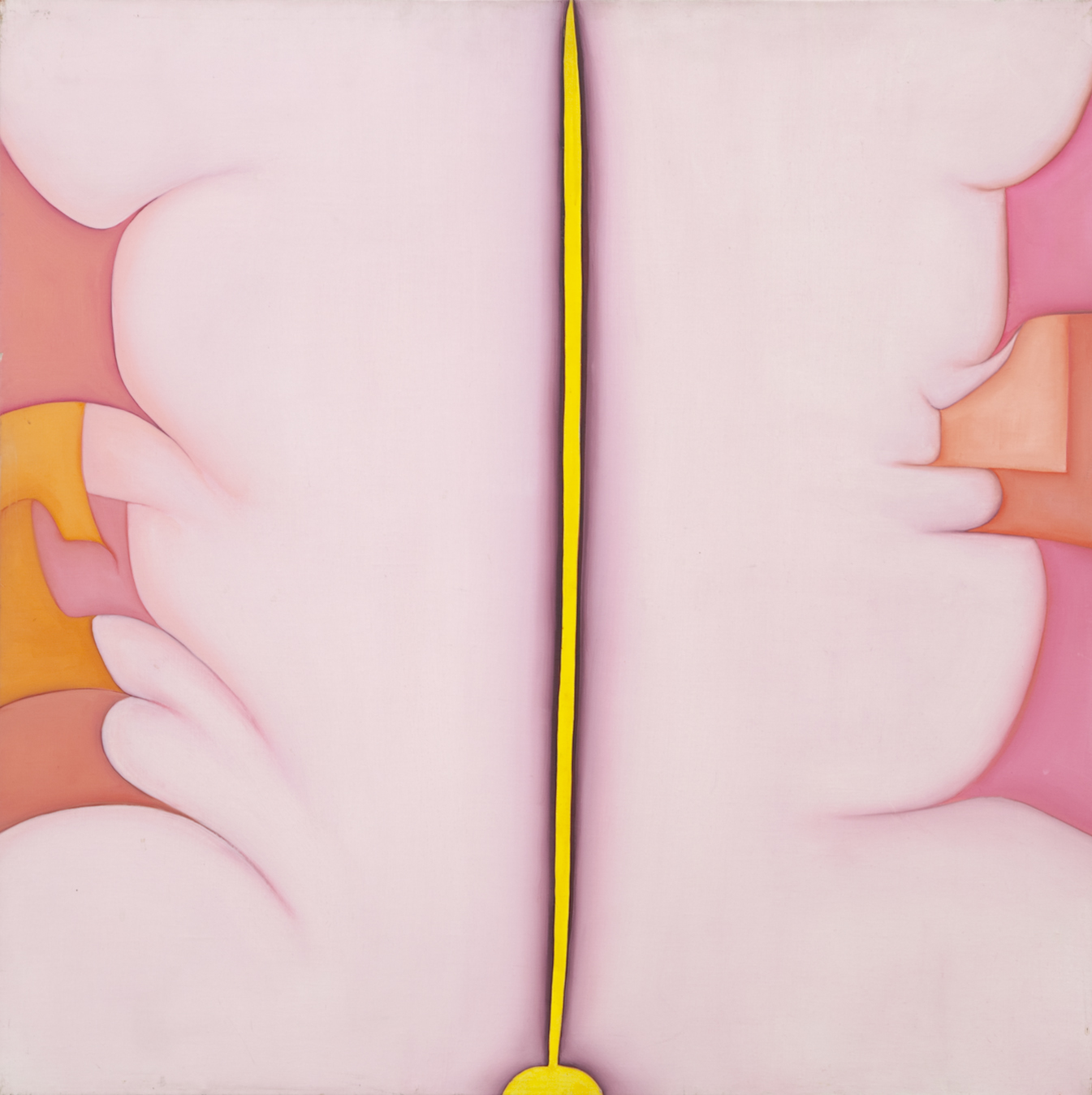

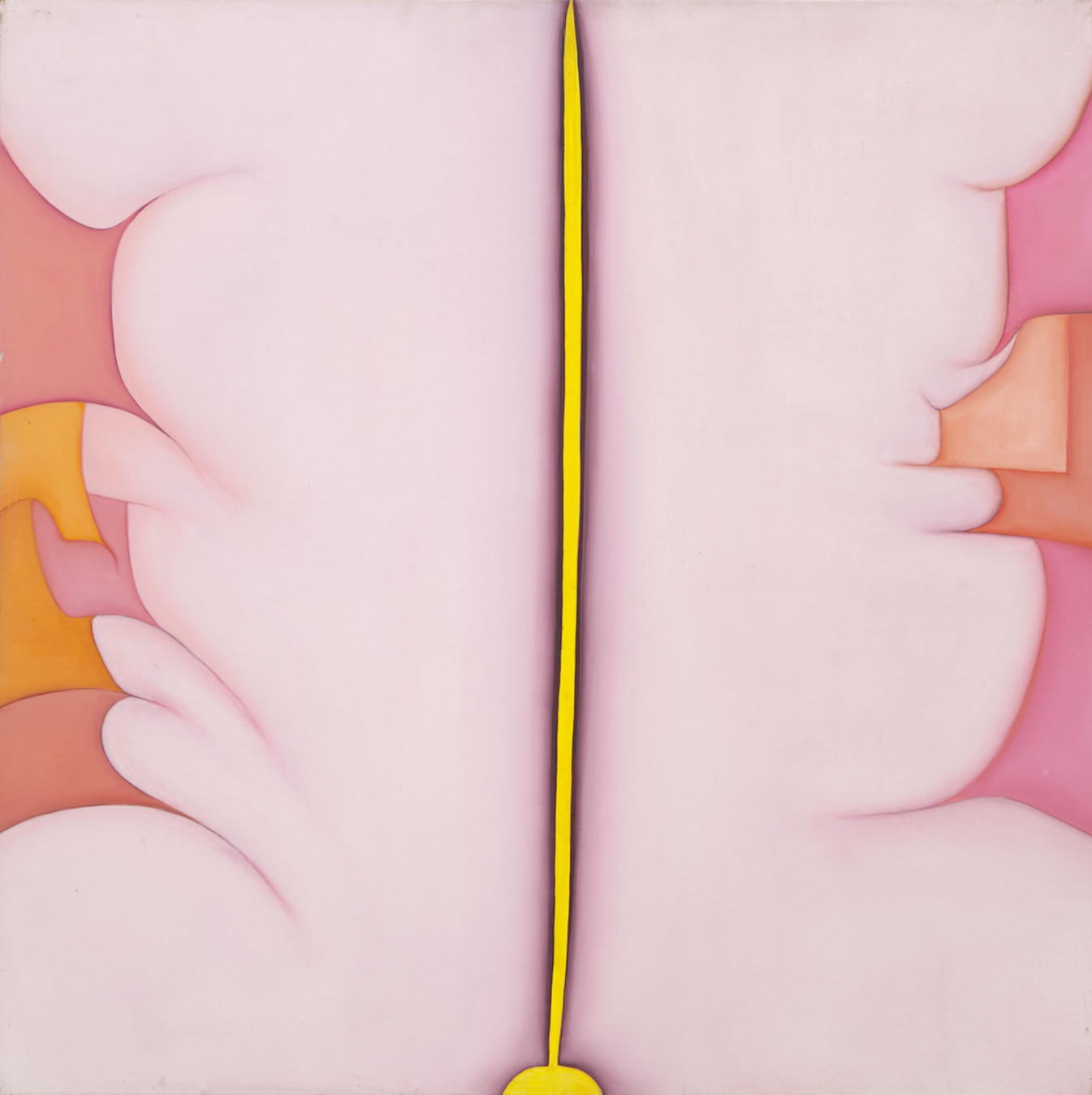

Huguette Caland, “Self Portrait (Bribes de corps), 1973, oil on linen, 47 x 47 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Huguette Caland: A Life Coming Into Focus

Share:

I came to Huguette Caland’s work too late, but haven’t we all? The octogenarian artist has been prolifically weaving and casting spells through her intricate lines on paper and canvas with delicate eroticism for more than 40 years, first in her native Beirut, then in France, and finally in Venice, California, where she lived for more than 20 years before retiring to Lebanon. To write comprehensively of Huguette Caland’s work is difficult: she is, arguably, one of the greatest Arab artists to have emerged since the 1970s, yet so little is written about her that each word put to paper carries a particular weight—a burden to represent a practice that is polyphonous, rhythmically enchanting, and as innately intricate as it is majestic. Caland’s work has the capacity to phenomenologically move the soul in the most unexpected of ways.

Almost two years ago, at the invitation of her daughter, Brigitte Caland, I walked into Huguette Caland’s house in Venice. Her former home was so inflected with Caland’s singular artistic vision as to constitute a testament to her sense of rapture with the world. There were no doors; everything was wide open, as she likes it. In the kitchen, her singularly unwavering line took over the walls surrounding her cabinetry, appearing over and over again in ebullient and striking color. As we ascended to the second floor, the bedrooms also bore no doors. The closets were empty, but they beckoned me to enter. There, painted directly onto the wall; the hanging rod that entered both figures’ mouths, at either end of the closet, a suffocating phallus.

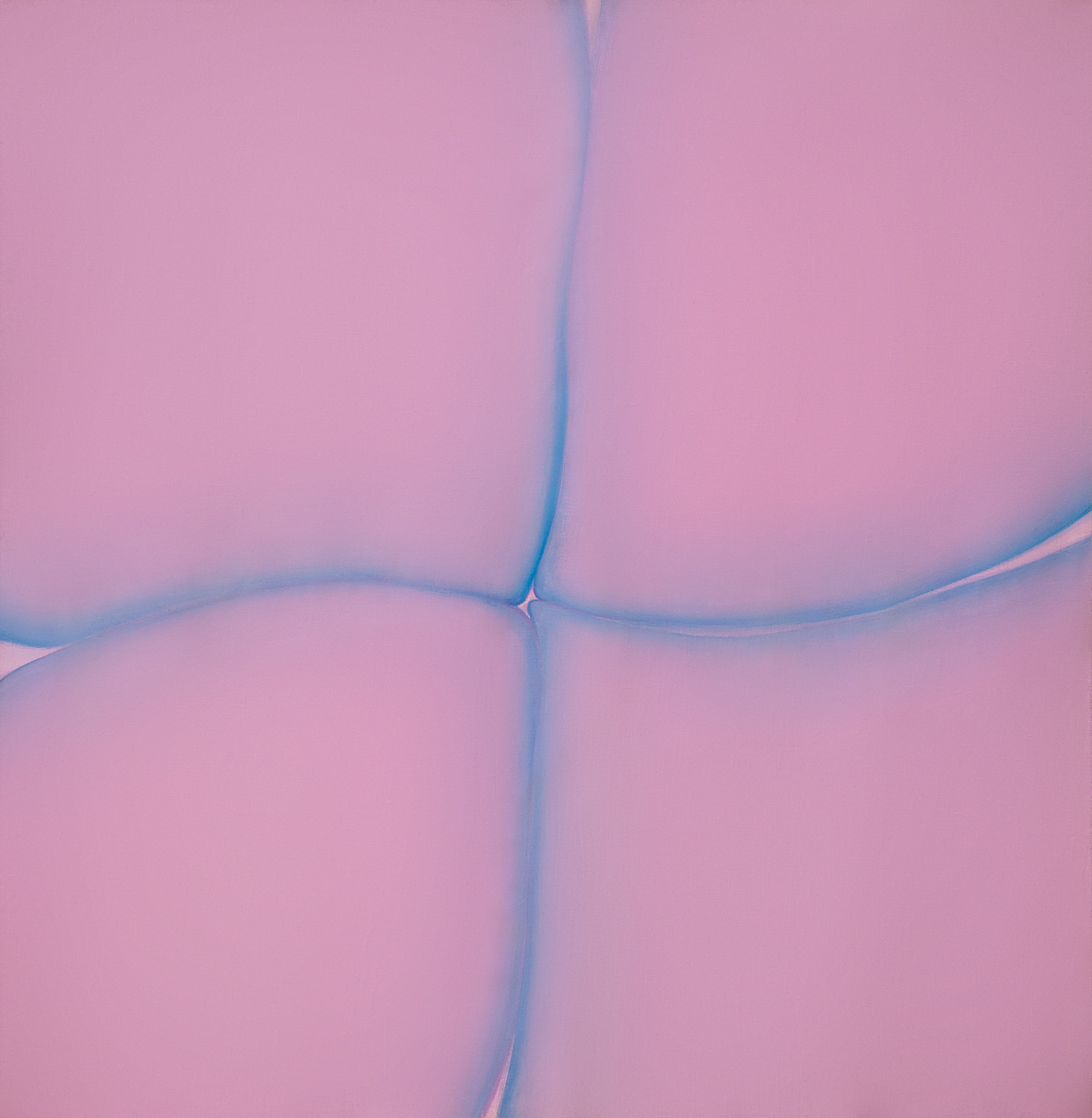

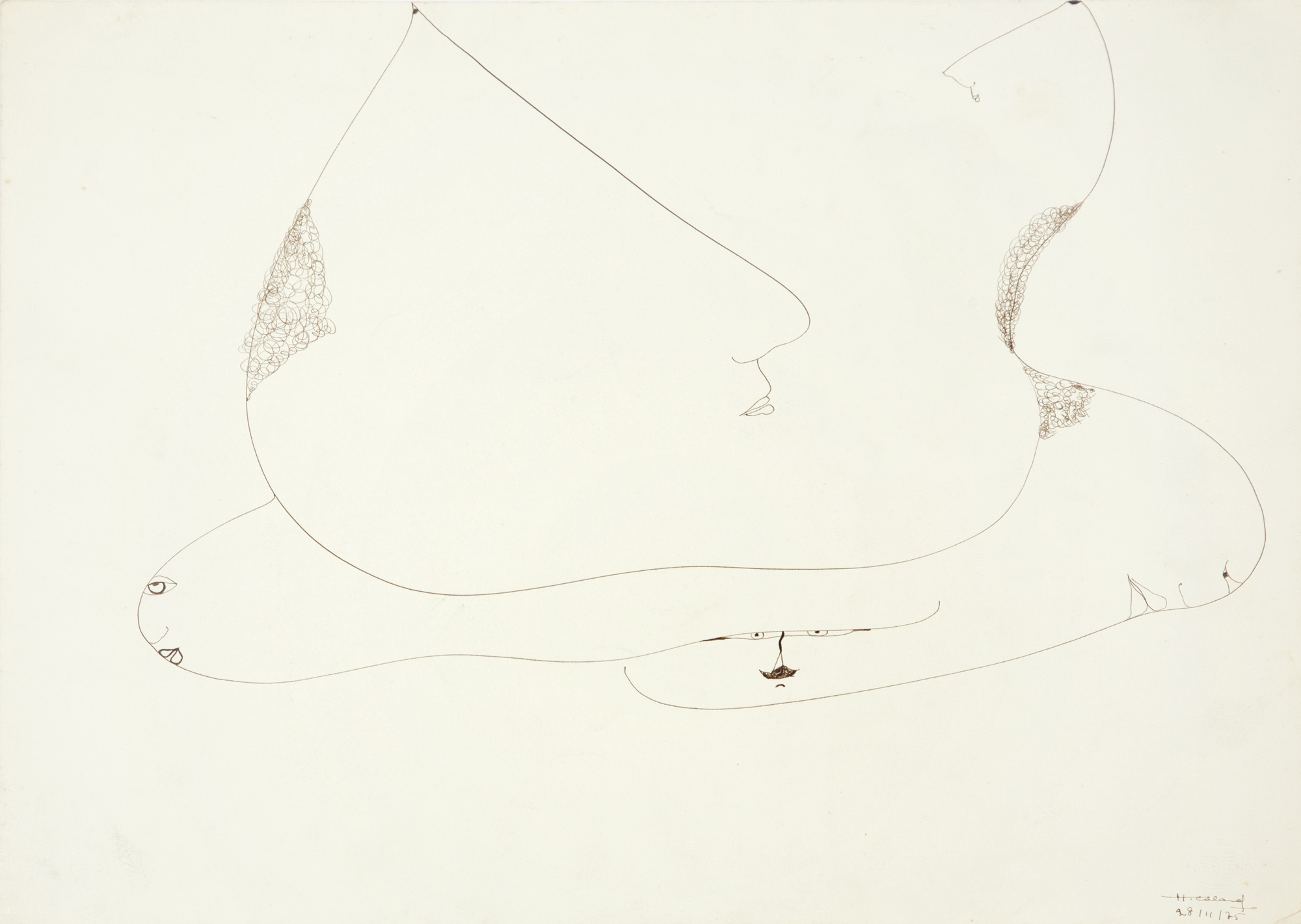

Huguette Caland, Bribes de corps, 1973, oil on linen, 36.5 x 29 inches [courtesy of the artist]

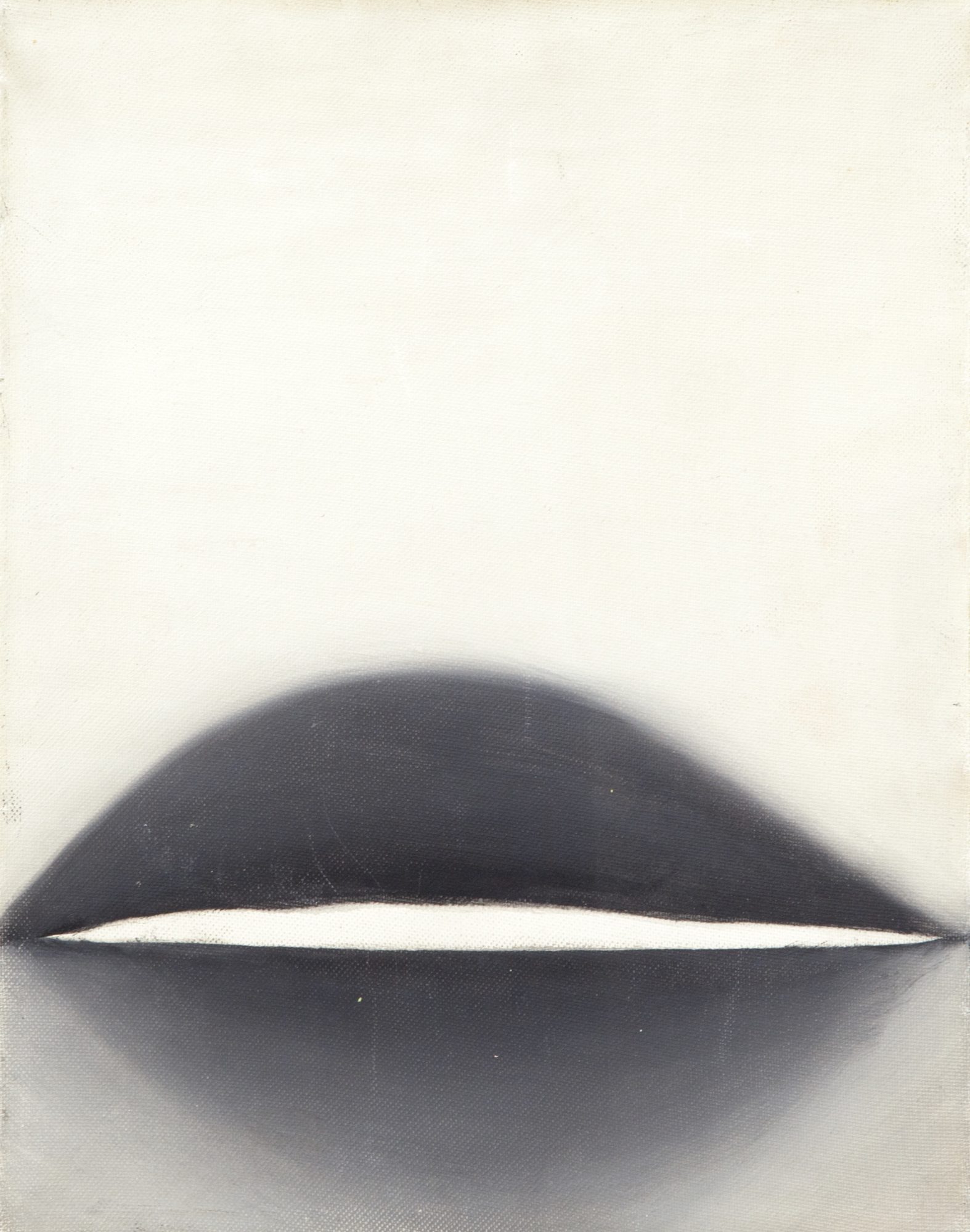

Huguette Caland, Bribes de corps, 1973, oil on linen, 11.7 x 9.3 inches [courtesy of the artist]

I recall the floors being painted in bold colors. There was an outside terrace. The home was clearly in transition—a dream world about to evaporate, to pass hands from the matriarch to her son. Brigitte regaled me with stories of how the Los Angeles art world would gather for dinner and parties in this home. Often, Huguette would continue working while people gathered around her. Brigitte named the LA artists who frequented the house, of whom the most prominent and important to Caland was the since deceased Ed Moses (1926–2018), a dear friend whom she often painted in abstract form. Articles that I have read on Caland refer to her as the “Gertrude Stein of the L.A. art world,” a force and an anchor, and yet her legacy is absent not only from that city’s artistic history but also from the global canon of feminist art.

Brigitte took me to the studio adjacent to the house. There, we unearthed giant sheaths of paper etched with bodies in black and white and in color; notebooks filled with erotic drawings and poems; massive canvases marked with abstractly sensual figures and lines, as well as with voluminous forms that advanced the formal limits of what abstraction could be through the sense of sensual abandon contained within them. I came back to LA a few weeks later to see that curators Aram Moshayedi and Hamza Walker had dedicated an entire gallery to Huguette Caland’s work in the Hammer Museum’s 2016 Made in L.A. biennial exhibition. There, Caland’s luscious “body fragments,” as she calls them, were presented alongside erotic caftans—clothing that she had made first for herself in Lebanon as (the Los Angeles Times once observed) “a step toward … self-acceptance” and developed into the 1970s after relocating to France, where she would collaborate with Pierre Cardin.

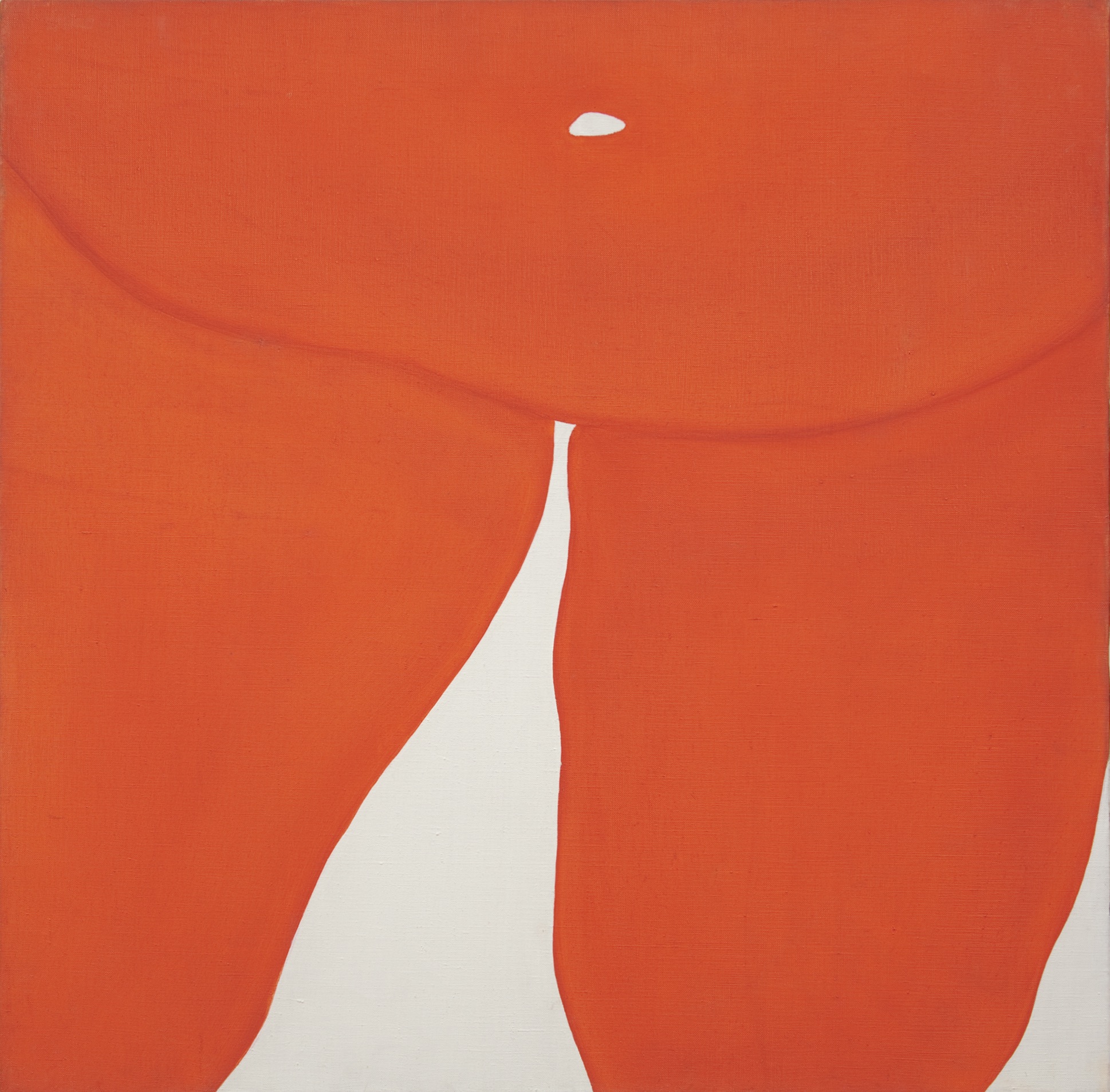

Huguette Caland, “Red II,” 1974, acrylic on linen, 31.5 x 31 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Huguette Caland was the only daughter of Bechara El Khoury, the first post-independence president of Lebanon—a hero of Lebanese nationalism who served from 1943 to 1952. (She had two brothers. Khalil died in 200; Michel is now 91.) But she was to disappoint her father by falling in love with a French-Lebanese man, Paul Caland, the nephew of El Khoury’s greatest rivals. She had three children with Paul Caland in Beirut, but she also soon took a lover called Mustafa before she decided to leave her children, her lover, and her husband for Paris. In the 2018 monograph Huguette Caland: Everything Takes the Shape of a Person, 1970–78, essayist Kaelen Wilson-Goldie quotes Nadine Beghdache, daughter of Caland’s Lebanon gallerist Janine Rubeiz: “Huguette was a free woman and it was too much for Beirut … the place for women in society was really changing.” At the time, Caland was painting nudes, which reportedly caused speculation and shock about her morals among members of the local art scene.

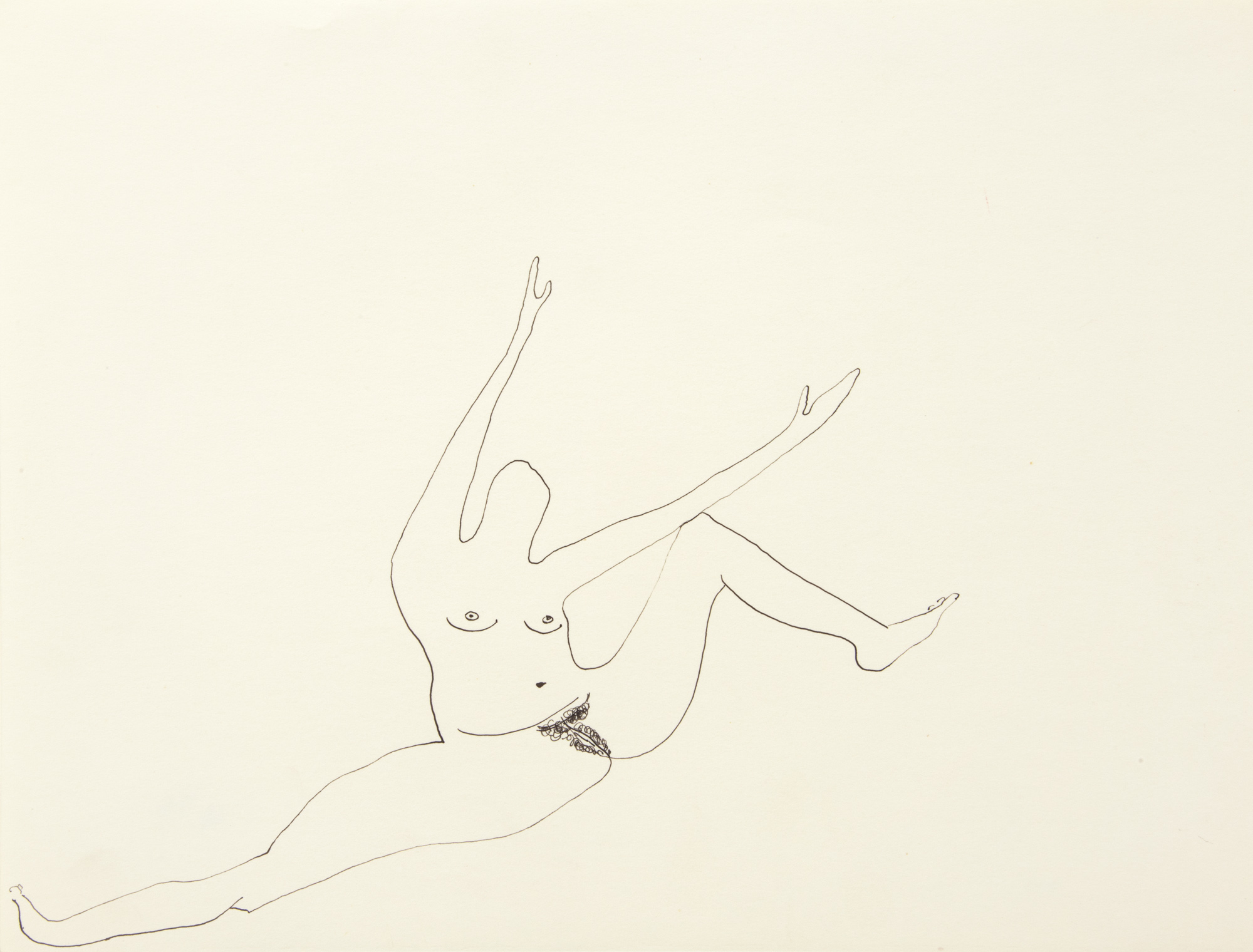

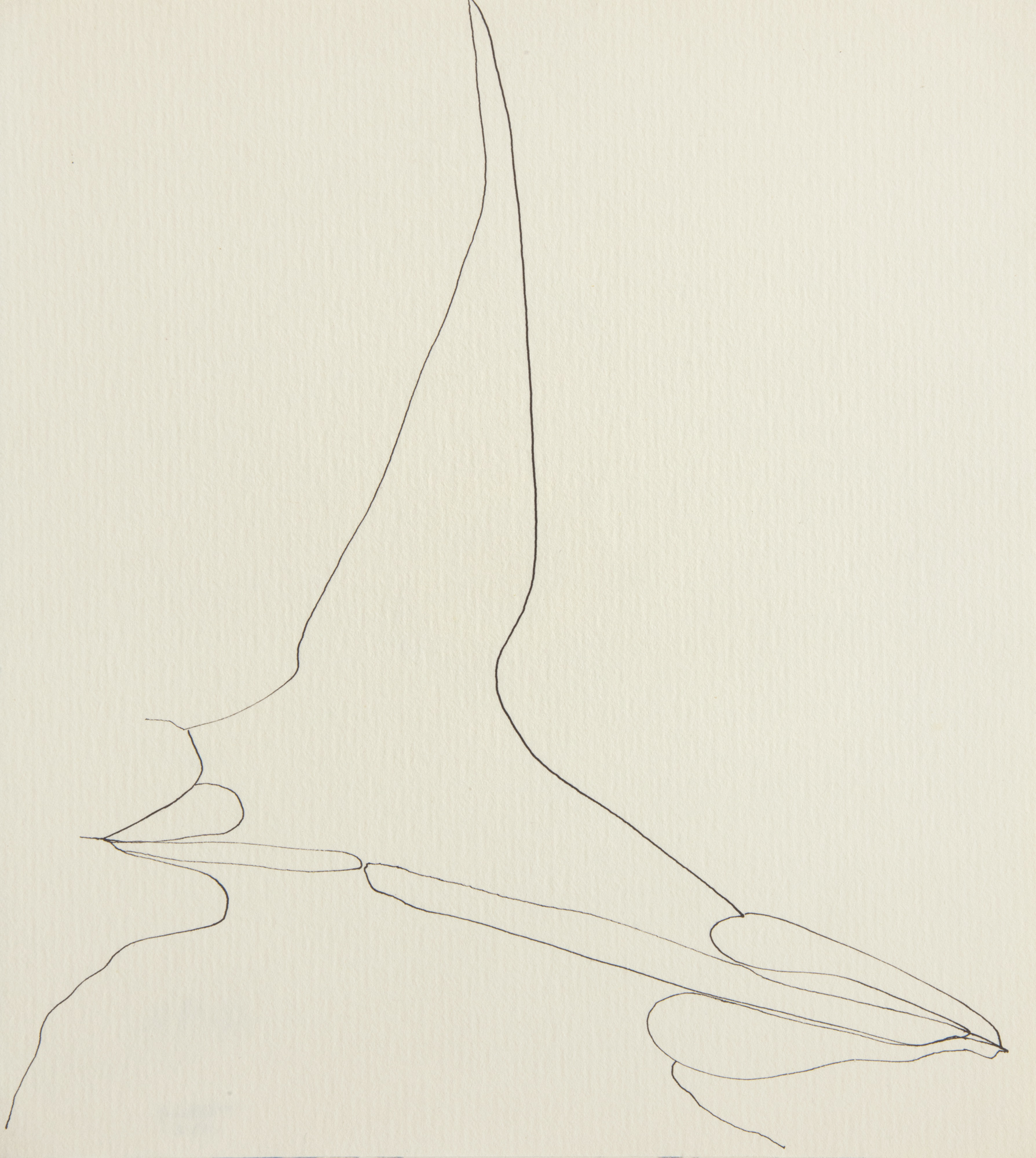

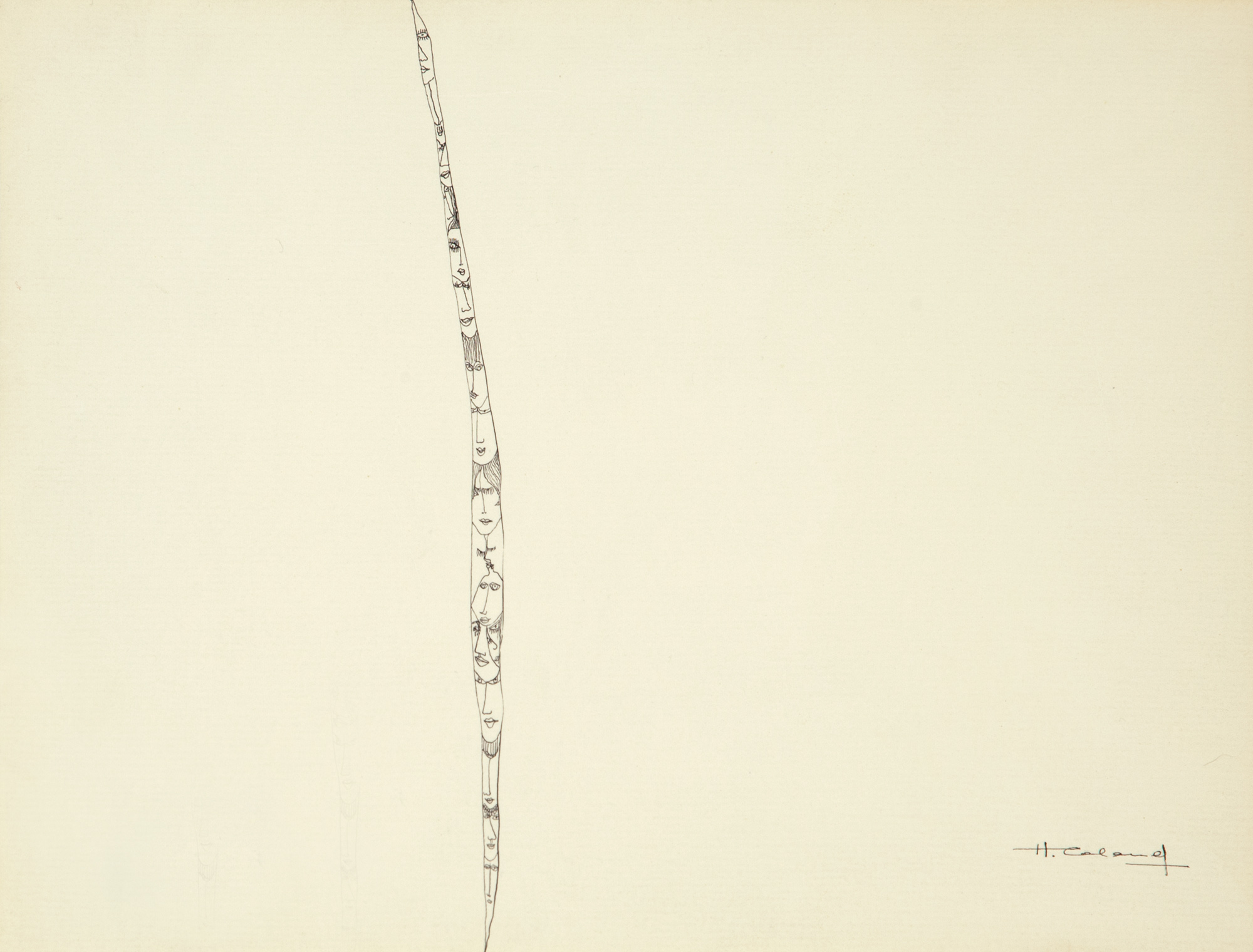

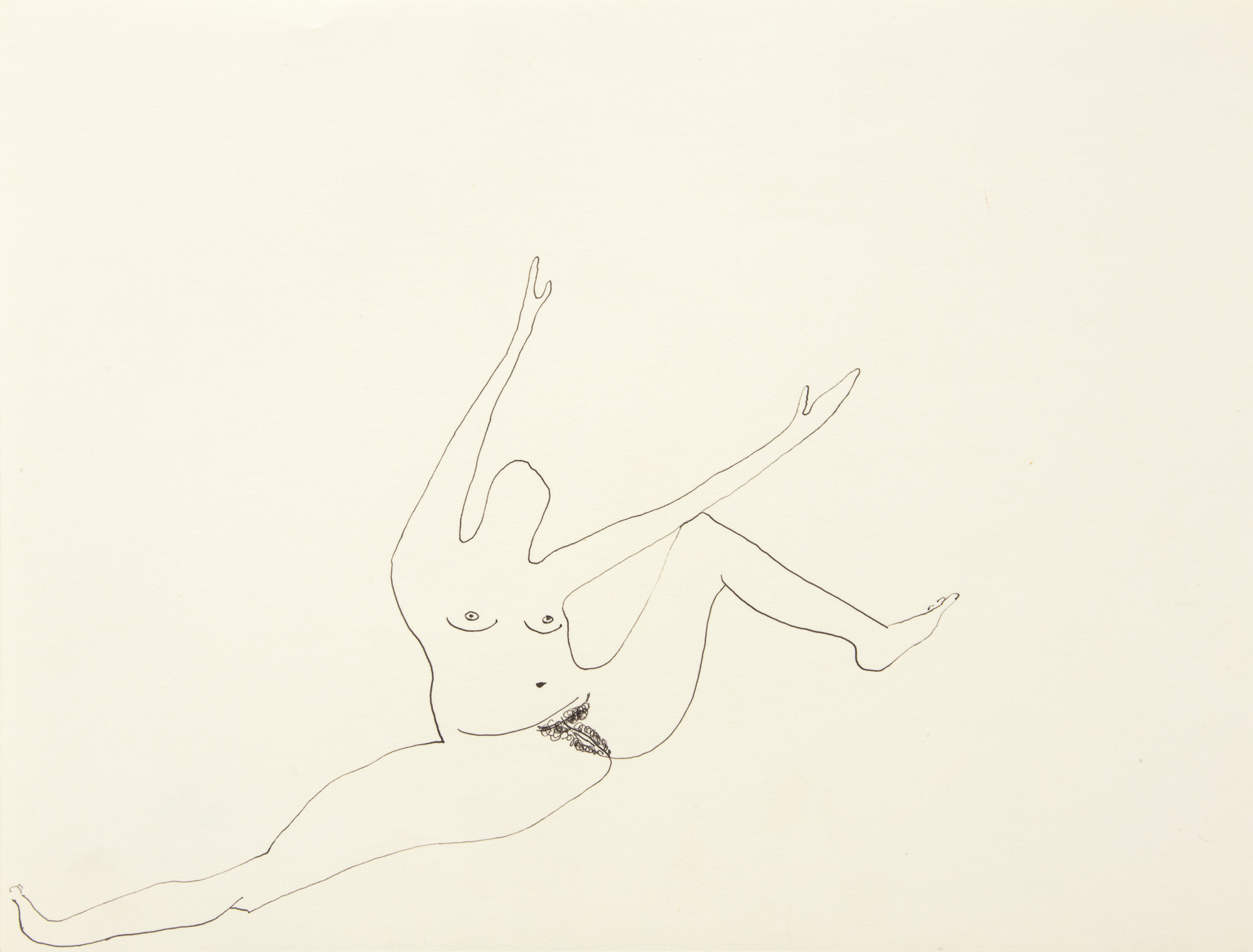

Caland came to art somewhat late in life, beginning her studies at the American University in Beirut in her 30s. According to Wilson-Goldie, she was taught to focus on the potentialities of the line. Starting with a pencil at the top of the page and drawing without breaking the line was a routine exercise required of her. This line has defined the artist’s practice from the very beginning, but not until the 1970s would it lead her to create her most potent work. In Venice, Brigitte, alongside her mother’s studio managers/conservators/archivists Malado Baldwin and Richard Flaata, showed pages upon pages of drawings, in which Caland’s evolved line extended to the corners of each folio with an unbridled wildness: limbs transformed into landscapes and landscapes into overtly sexualized body parts.

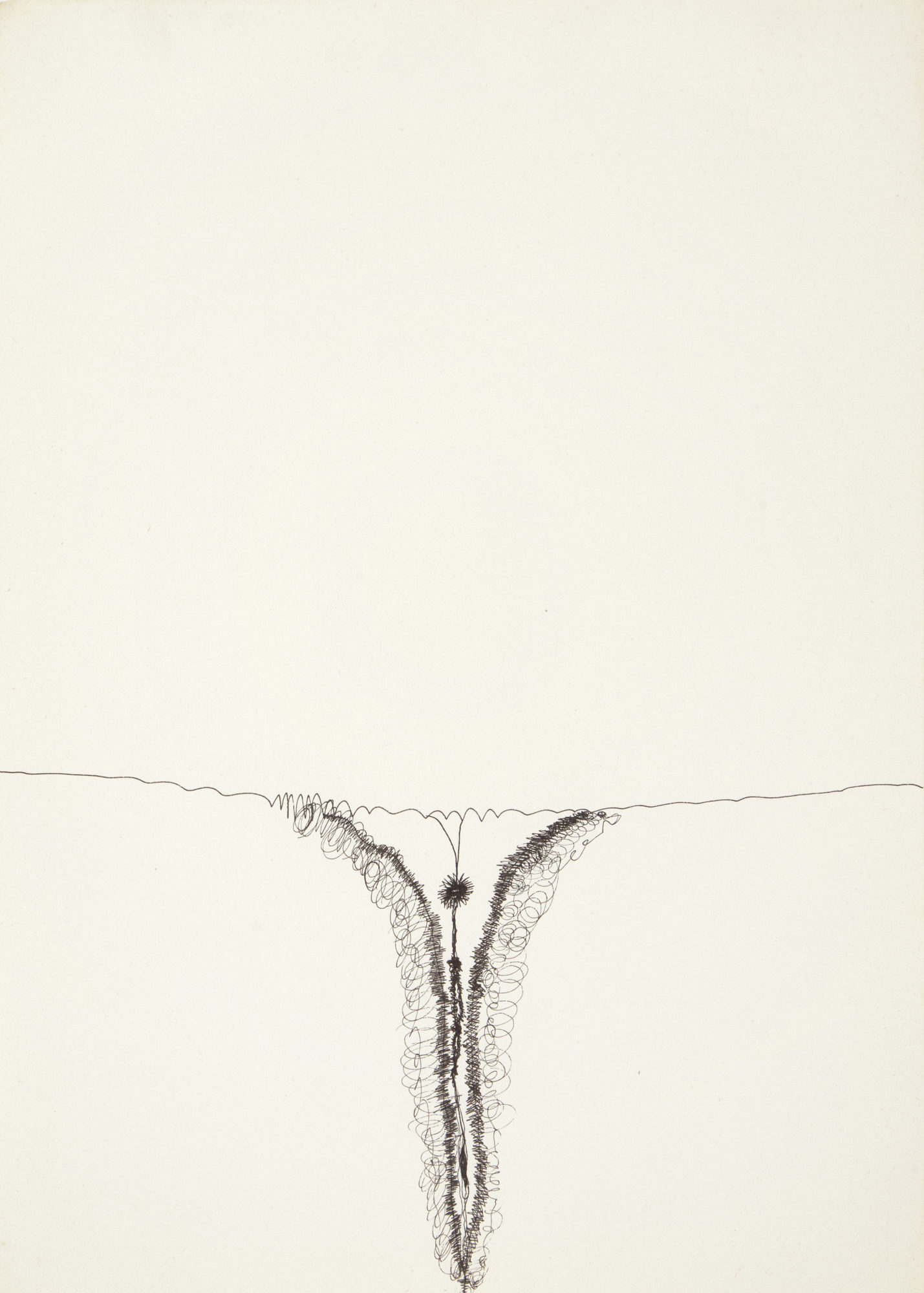

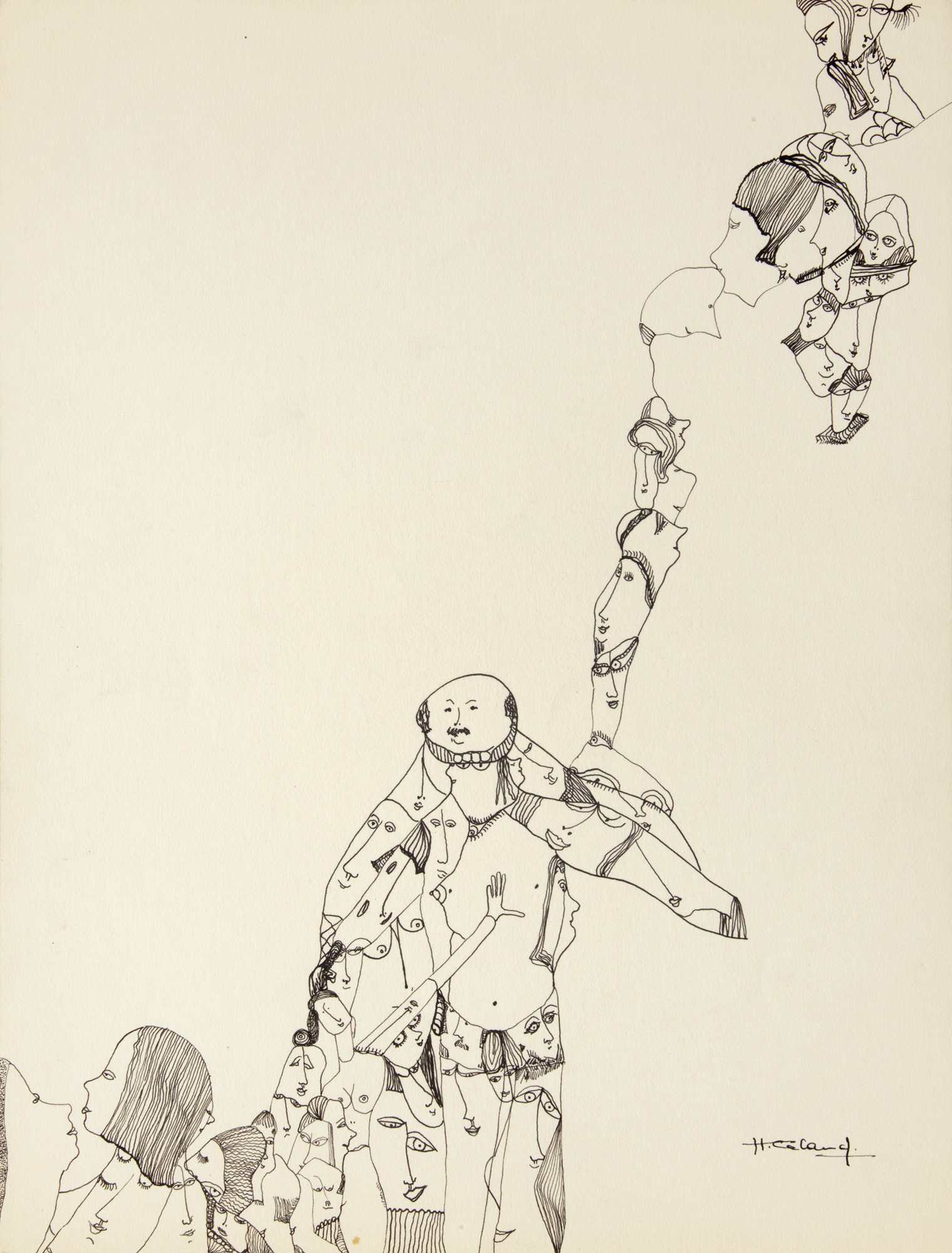

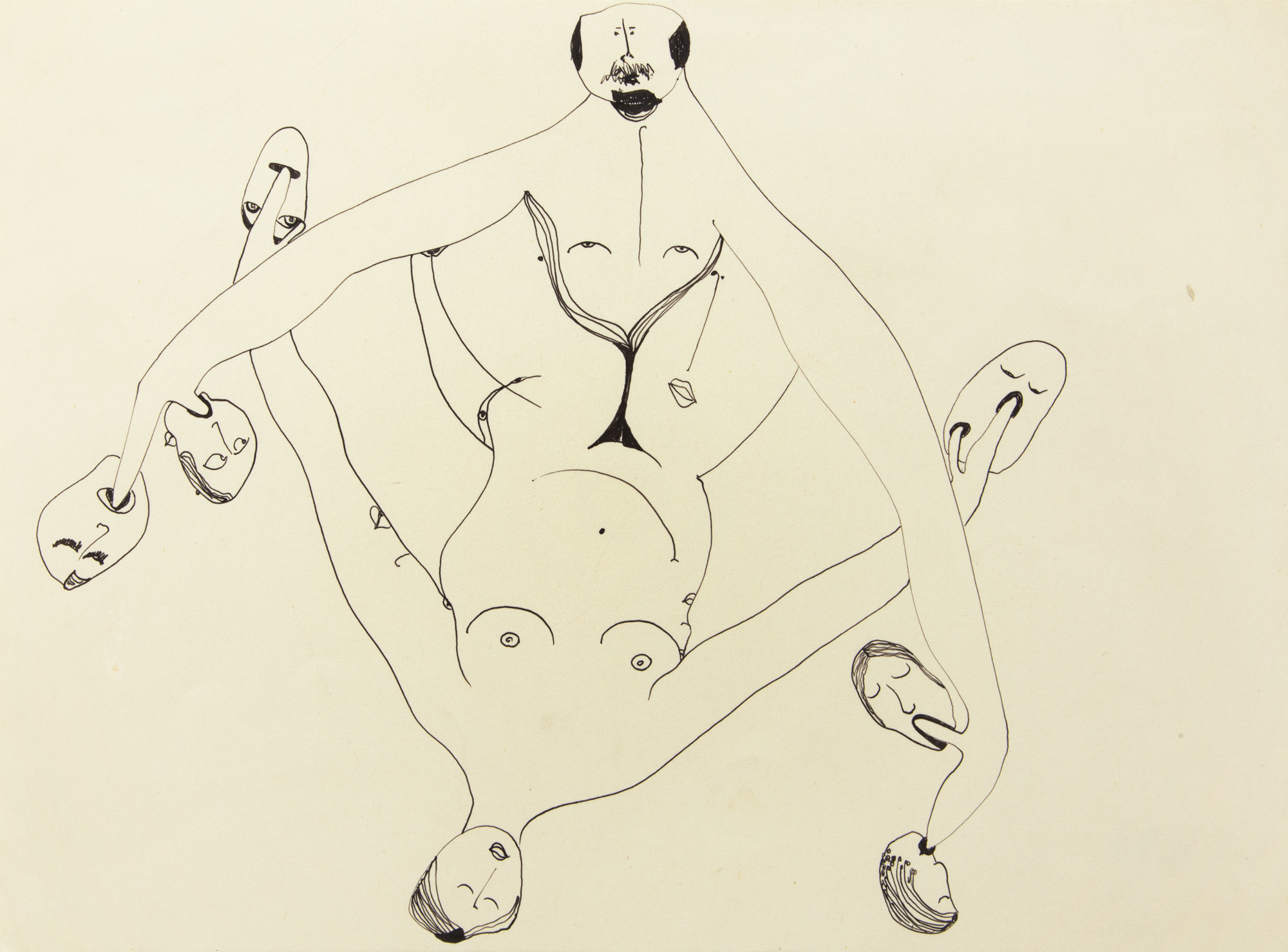

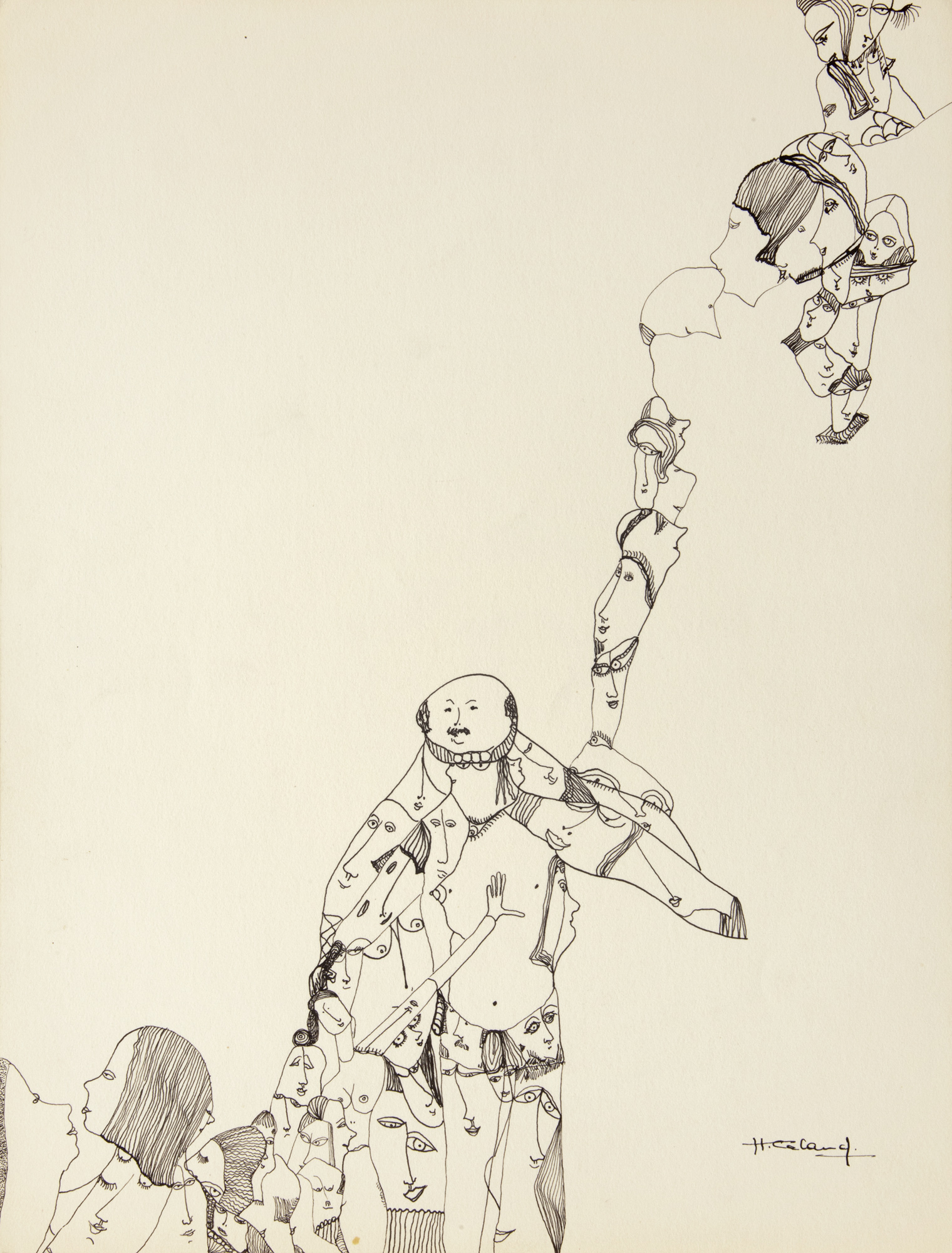

In Moustapha, poids et haltéres (Moustapha, weights and dumbells) (1970), we see a drawing of the artist’s Beirut lover: a round-faced man grasping at his chest while other figures— dozens of faces, intermingled— float in free form above him, all the way to the edge of the page. With Self-portrait (Bribes de corps) (1971), Caland began her “body fragments” series with a line that descends into the core of the page to form a flower amid a tuft of public hair; here is where the metaphors underlying her renderings crystallized. In Moustapha acrobate (1971), her lover takes the form of an Olympian, anchoring a great number of men and women —perhaps an allusion to his sexual prowess and versatility.

Huguette Caland, Untitled, 1971, ink on paper, 14 x 10 inches [courtesy of the artist]

Hugette Caland, Moustapha, poids et haltères, 1970, ink on paper, 12.5 x 9.5 inches [courtesy of the artist]

A drawing of Caland’s husband, titled Paul (1971), appeared in the same year. Its caricature of a suited man has a female face poking out curiously from between his legs, while a number of other feminine forms, draped across his sleeve, kiss his feet. Paul is characterized here as a traditionally corporate character, in contrast with the thick-limbed Moustapha who appears in previous drawings. Two men, one languid and one hypermasculine: was she negotiating, through lines, her love and lust for both? Or depicting the anxiety of having to choose?

Outstretched before us in il se passes des choses (Things are happening) (1971) is a universe of thinly drawn men and women in decadent liberation —perhaps an allusion to the sexual emancipation of the 1970s; or to the decadent poetry of fin de siècle poets such as Paul Verlaine, who left his wife and family for a life of romance with Arthur Rimbaud many years earlier. Certainly these finely etched lines convey both a poetry and a lyricism. They are akin to musical notes on paper—songs of debauchery so methodically choreographed that it would be impossible ever to perform them.

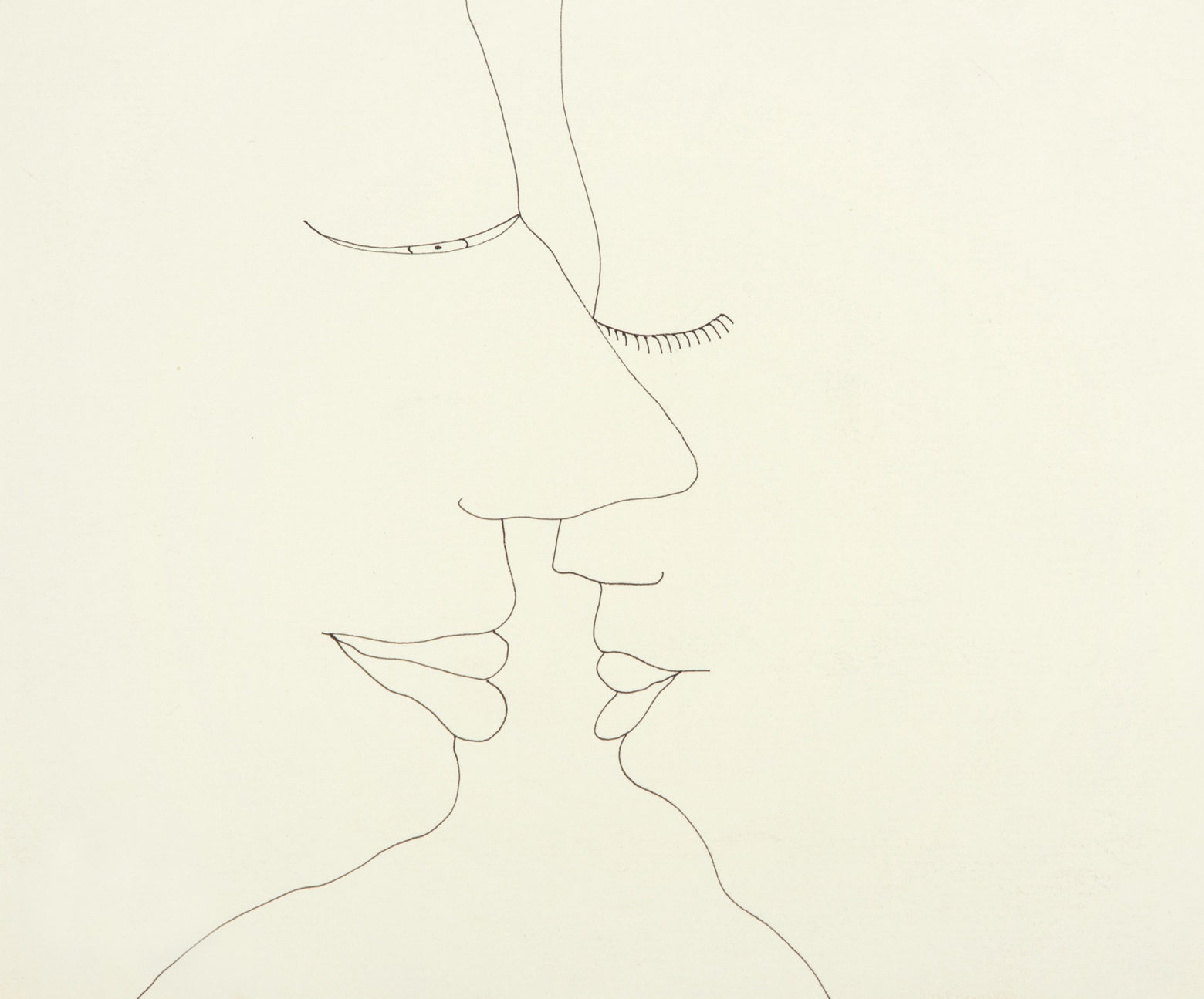

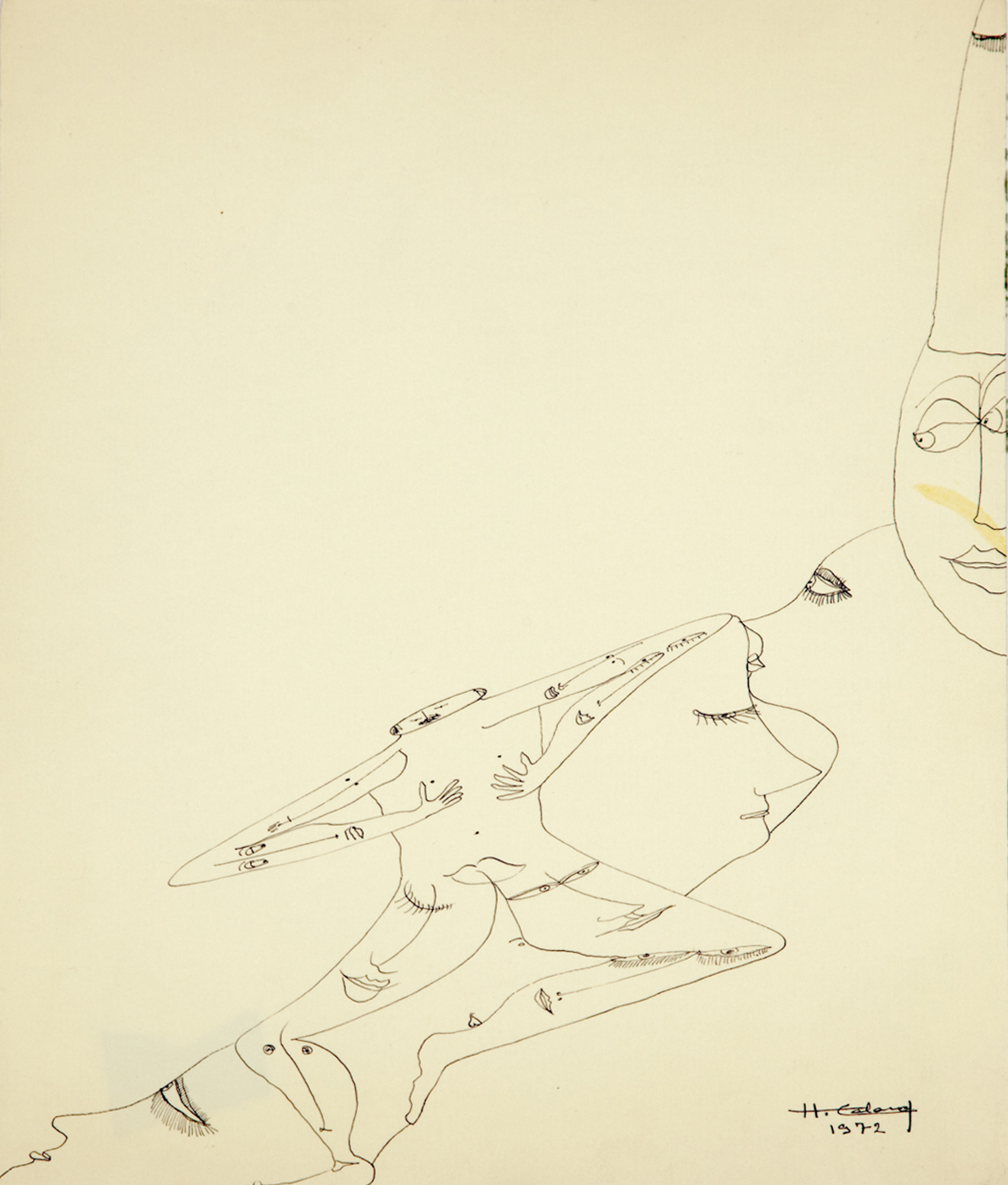

Caland’s Flirt series (1972) reveals her abstract lines at their most simple. Is that a snout, a nose? Are we looking at two flowers enmeshed together? Or is it a pair of lips kissing in perpetuity, abstracted, or tentatively reaching for each other only to dissipate upon contact? A mouth entering an orifice? Are we witnessing a woman pleasuring herself? Caland’s are pictures of endless possibility—the possibility of liberated rapture, of a limitless euphoria removed from the confines of any societal norm or function.

Huguette Caland, Hi!, 1973, ink on paper, 9.5 x 12.5 inches [courtesy of the artist]

In an untitled work from 1972, a shape sits before us. It may be an eye or a mouth, clasping what look like hundreds of female faces, squashed together. Are they struggling to be seen, devoured by a greater whole? Are they seeking a voice? A voice that has value and meaning in this world? In another untitled work, one from 1973, a cavalcade of circuitous hairs unfurls to resemble the strata of the earth. Closer inspection reveals they form tiny bodies, floating in paradise. A large question remains: that of Caland’s ultimate intention with these works. To catalogue all their art historical or formal resonances would be too large an undertaking, but what one can see in each piece, and what each bears witness to, is an ultimate desire for a life surrounded by the liberation of sexual possibility. Emigrating from one country to the next, Caland found communion in her love of the body and in the unbridled possibility of celebrating it, free of judgment.

Caland’s paintings from the 1970s embrace another phenomenology: they are physically large and, thus, confront the body in space. You are put on the spot by an image that you must interrogate to understand and that questions your own sense of desire. Her oil on canvas Enlève ton doigt (1971) (remove your finger) is both a command and a celebration. A figure with sumptuous lips sits enraptured at the edge of the painting, sucking on a voluminous hand that in turn melds into a series of contorted figures—again caricatures of men abstracted, stretched, and hung up as though to dry. The artist is in control of her sensuality here: she will set the rules and determine the function and manifestation of her desire. She will speak in whichever way she pleases.

One work in the Bribes de corps series (1973) is a large oil on linen canvas, in which a pink balloon-like form resembling a soft and inviting pouf, something to sit on, invites you in to offer you comfort. A closer look reveals a series of cracks in the paint, two purple shapely mouths taking in a piece of silky skin from each end, or two crevices—one on top, the other below—recalling a landscape of mountains. Or are they body parts ascending into a state of euphoria from mutual pleasuring?

Caland’s are pictures of endless possibility — the possibility of liberated rapture, of a limitless euphoria, removed from the confines of any societal norm or function.

Huguette Caland, Bribes de corps, 1979, oil on linen, 31.8 x 31.8 inches [courtesy of the artist]

One of the most striking paintings in this series is Self-Portrait (Bribes de corps) (1973), another large oil on linen. Here two faces, or two bluish-purple half-visages, each with hollowed eyes, converge; beneath them is an emptiness—a gap, and an upset pair of lips. Could this be a fragmentation of the soul? Two sides of a personality attempting to reconcile with each other? Two spirits—or two bodies—becoming a whole? Another Self-portrait from 1973, which is in the family collection, engulfs the imagination with its sheer simplicity. It is a perfect pink form suspended in air. Peer closely and you will see the perfect, taut form of a butt crack made visible, defining two magnificent cheeks resting on an unknown beneath them. One of the most intricate works in the Bribes de Corps series also comes about in 1973. A yellow landscape—it could be the sea, or perhaps the sand—forms a backdrop; as one’s gaze follows this panorama, it begins to resemble a mountain range, each end of which provides a sudden encounter with what appear to be perfectly formed, thin red lips. Layered upon this backdrop are more of Caland’s intricate drawings, indiscernible shapes and bodies ensconced within the bosom of these two mounds. A subtle figure is ejected from the mouth at one end like a tapeworm leaving the body—an exorcism of sorts, although its eroticism remains.

After the 1970s, Caland continued to unfurl her line into new territories. Faces transmuted into geographies, landscapes, cities, chronoscopes, memories, and other constructions that stretch the limits of the imagination. I still struggle to describe the power that Caland’s simultaneously muted and effervescent drawings and paintings have over me; to articulate their potency would require sustained investigation not simply into the works, but into the self. What’s certain is that Caland, a Lebanese artist, an Arab artist, was pioneering a subject and an aesthetic that had rarely, if ever, been tackled before by an Arab woman with such will and dedication, or such passion, style, and efflorescence. She is due further examination and a place within the canonical realm, not only of Arab art but also of feminist art, of erotic art. Indeed, her work possesses an erotics of the body that engages not only the subject depicted, but the senses of anyone who is interested in looking. Hers is a world that interrogates the very function of looking and asks viewers to consider, time and again: what am I looking at? And why should I be looking?

A woman looking to be “heard” is a voice that calls out to me. Although Caland’s life’s work is only now coming into focus, and although we have all arrived too late to the table, now is the moment to recognize those who have sought to have a voice. For immigrants in a free-falling world, the “welcome” is most often temporary—the result of a fad or fleeting sympathy—and quick to turn into a refusal of the diasporic voice. We will make sure that she and others like her will never be forgotten.

Huguette Caland

Omar Kholeif is a writer and the Manilow Senior Curator and Director of Global Initiatives at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. His forthcoming books include “Goodbye, World! Looking at Art in the Digital Age” (Sternberg Press) and “The Artists Who Will Change the World” (Thames & Hudson).