Historians of Exile

Share:

New York: what a concept. Its goliath-sized buildings and crowded streets have called to people around the world with promises of adventure and success. In many ways, the city has become a primary site for the neoliberal mythologies of the American Dream. Romantic stories of people trying to “make it” in New York through their own ambition and ingenuity have become ubiquitous to the city’s depictions—in literature, art, and film— so that a once potent narrative of struggle has lost its bite. Icons of experimental filmmaking Chantal Akerman and Jonas Mekas explored New York from the perspective of someone caught between their birth-home and the city, struggling to relate to cultures on either side of the Atlantic. The filmmakers chronicled their journeys as European immigrants, addressing their traumatic family histories by interweaving them with their own stories of displacement in New York. Mekas and Akerman use similar aesthetic and thematic cues to reflect the loneliness and isolation of their immigrant experiences and their longing for community. Akerman’s News From Home and Mekas’ Lost Lost Lost document the artists’ experiences as immigrants through intimate narration, New York’s sprawling expanse as imagery, and thematic focus on the family unit amid the lingering trauma of World War II to tell the story of their creators’ first years in the United States.

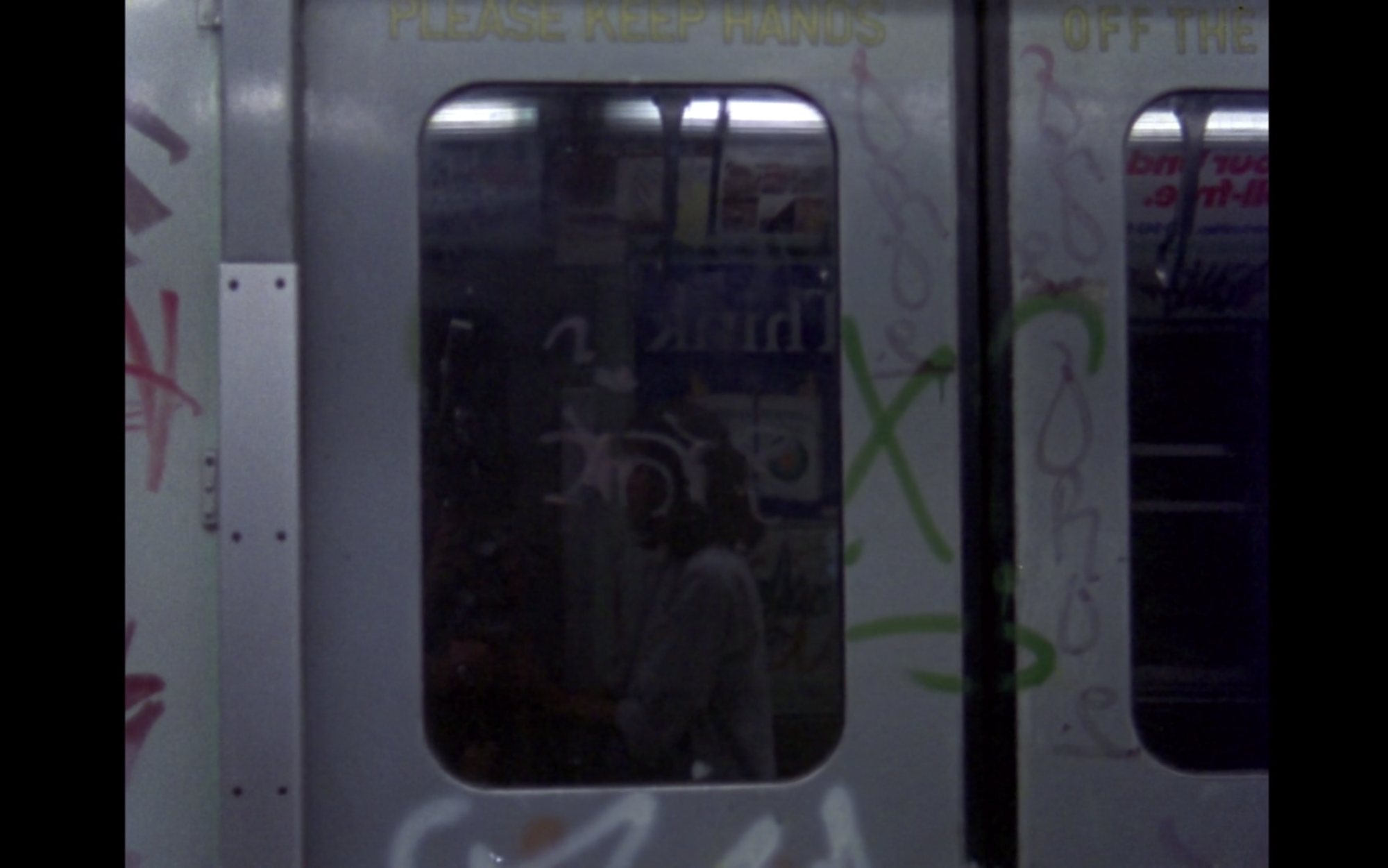

Chantal Akerman, screenshots from News From Home, 1977, film, 1H 28M [courtesy of Youtube]

Mekas and Akerman both arrived in New York as young adults, and once there, they followed similar trajectories as experimental filmmakers. Akerman left her native Brussels in 1971 and lived in Manhattan for a year and a half, working odd jobs while writing scripts and developing her first films. In addition to the films she made in Belgium during the 1970s, Akerman filmed and released the first of her “New York films,” beginning in 1972 with Hotel Monterey before shooting what would be News From Home with her longtime collaborator and cinematographer, Babette Mangolte. The experimental documentary consists of long shots of New York’s empty early-morning streets, grimy subway cars, and late-night downtown haunts, narrated through voiceover by Akerman that consists of the concerned yet loving letters her mother, Nelly, wrote to her during that time. Rendered in her and her mother’s native French, Nelly’s letters read by Akerman constitute a sensitive document of their growing pains. We never hear Akerman’s responses to her mother’s letters, but the New York scenes offer a visual answer to Nelly’s concerns about Chantal’s happiness, safety, and security.

Jonas Mekas, screenshots from Lost, Lost, Lost, 1976, film, 2H 58M [courtesy of Youtube]

Jonas Mekas, screenshots from Lost, Lost, Lost, 1976, film, 2H 58M [courtesy of Youtube]

Mekas’ Lost Lost Lost is similarly told through fragments of film, memories, and sound; its filming began in 1949 and stretched through the 1950s and 1960s. Mekas and his brother Adolfas arrived in New York and settled in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which was then an enclave of Eastern European immigrants. With the addition of title cards, footage from unfinished films, and, in some cases, music, Mekas finds beauty, humanity, and sadness in New York’s immigrant citizens, exemplified by a particularly touching scene of a Lithuanian American picnic with traditional dancing and costuming, all seen in beautiful color that contrasts with the dominant black-and-white imagery in the rest of film. As Lost Lost Lost progresses, we see Mekas’ early days at the Film-Makers’ Cooperative and, ultimately, his epiphany: that he has found a family, in New York, through his brother, their friends, and their colleagues in the growing independent film community of the city’s downtown. These vignettes end with Mekas and his friends’ experimental short films about life, transformation, and time, shot in the dead of winter.

Chantal Akerman, screenshots from News From Home, 1977, film, 1H 28M [courtesy of Youtube]

Time’s passage and its link to mortality weigh heavily on Akerman and Mekas, reflected in the inclusion of excruciating details about home, location, and self. Akerman’s News From Home discusses family through Nelly’s short dispatches in her letters. She mentions the birthdays, engagements, and other life events involving the family Chantal left behind, including the birthday of Chantal’s teenage sister Sylviane. More distressingly, by mentioning various sicknesses and unshakeable aches and stresses, Nelly also emphasizes the destructive effects of aging she and Chantal’s father are experiencing. Her parents also feel the effects of Akerman’s distance. In one of her letters, Nelly recounts, “Father dreamed about you last night. He was terribly shaken, because you came back and then you were gone …. Write soon. When he knows you’re doing well, his fears vanish.” Her mother also incessantly asks when Akerman intends to visit home and to write about her new life. Mekas addresses time through the change in seasons. The early footage in Lost Lost Lost includes scenes in local parks that show seasonal changes throughout the year. A turning point in Lost—and in Mekas’ life—is the move from Williamsburg to lower Manhattan, which is symbolic of his socioeconomic advancement from the communities in immigrant-dominant Brooklyn to the artistic groups near the city center. The viewer is made aware of time, not through a literal narrative but through the experiences the filmmakers have, or in Akerman’s case, miss. Time’s passage becomes a symptom of the filmmakers’ displacement, tracked through their loneliness.

Chantal Akerman, screenshots from News From Home, 1977, film, 1H 28M [courtesy of Youtube]

Lost Lost Lost and News From Home’s explorations of time and distance in relation to family are central to other “moving to New York” narratives, but what separates these documentaries from others is the shared trauma of displacement and alienation that resulted from Nazi Germany’s reign of terror, and the resulting power vacuum in eastern Europe after the end of World War II. Mekas’ isolation from home is double-sided: he experiences physical distance from home while also reckoning with the massive political and cultural changes that alienate him from the society he once knew.

The Mekas brothers grew up in Lithuania and immigrated to New York as refugees after their wartime imprisonment in the Elmshorn labor camp. In interviews Mekas said that the earliest footage in Lost was intended for a scrapped documentary about the displacement eastern Europeans like him faced as a result of the war, as well as the postwar political tensions that set the stage for Soviet-Baltic conflict.1 Decades after the initial documentary was abandoned, Mekas turned that footage into Lost as a means to discuss his homeland and his own displacement amid the Lithuanian community in Williamsburg; he regarded the work as a film “recorded by someone in exile.”

Jonas Mekas, screenshots from Lost, Lost, Lost, 1976, film, 2H 58M [courtesy of Youtube]

Jonas Mekas, screenshots from Lost, Lost, Lost, 1976, film, 2H 58M [courtesy of Youtube]

Akerman was a generation removed from WWII, but it haunted her throughout her life and filmmaking career. Born in Belgium, Akerman was raised within Jewish tradition by her mother, a Holocaust survivor from Poland who had been imprisoned in Auschwitz. Akerman herself had no lived experience of the war’s displacement and violence the way Mekas did, but her films—including her final film, No Home Movie—analyze maternal lineage and the collective memory of genocide. In late-career installation works such as 2004’s Marcher à côté de ses lacets dans un frigidaire vide (To Walk Next to One’s Shoelaces in an Empty Fridge), scholar Maureen Turim argues that in this work, Akerman directly addresses “the carrying of a legacy from generation to generation in a Jewish family marked by inheritances of the Shoah.”2 Akerman’s and her mother’s anxieties about the filmmaker’s move to New York and their letters’ preoccupation with family wellness show how the lasting effects of unspeakable trauma can destabilize family units, communities, and countries for generations.

As survivors and descendants of deep generational trauma resulting from war and power struggles, Mekas and Akerman defined their years in New York by their own journeys as well as the families and homes they left behind. Viewing Lost Lost Lost and News From Home as results of Mekas and Akerman’s complex relationships to family and home, we can analyze these two films as New York narratives that do not shy away from the emotional toll of immigration wherein hope for a new future is mixed up with remembrance of the past. Lost Lost Lost and News From Home are portraits of displaced young artists, but they are as much about their creators as they are about home, families we choose, and the people we choose to leave behind.

Madeleine Seidel is an arts writer and Masters candidate at Hunter College. She has previously worked at the Whitney Museum of American Art and Atlanta Contemporary. Her current research interests include American feminist art movements in the 20th century, curatorial practices in film exhibition, and the art of the American South.